What Would Freud Say About Mother’s Day?

Talking with Daphne Merkin about ‘American mishegas’

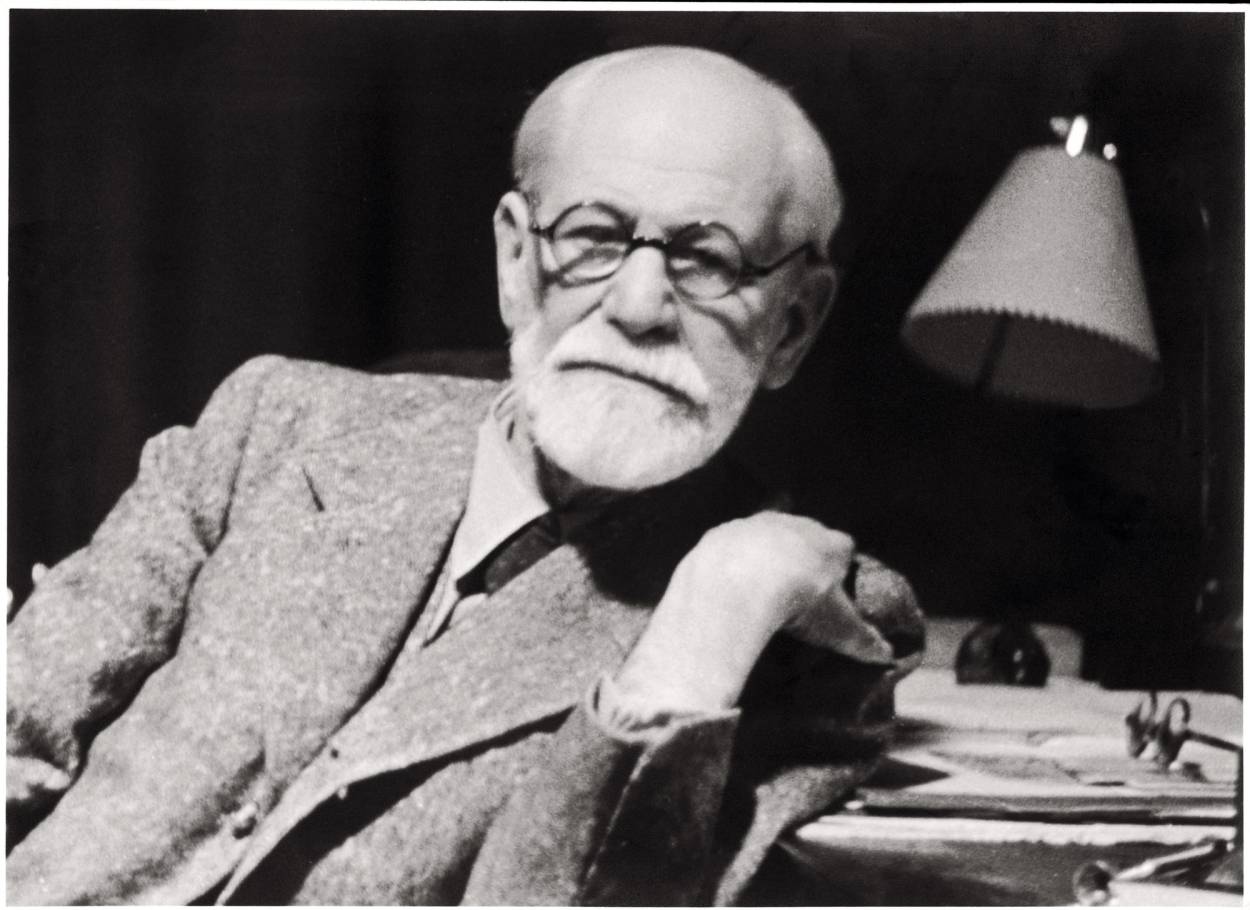

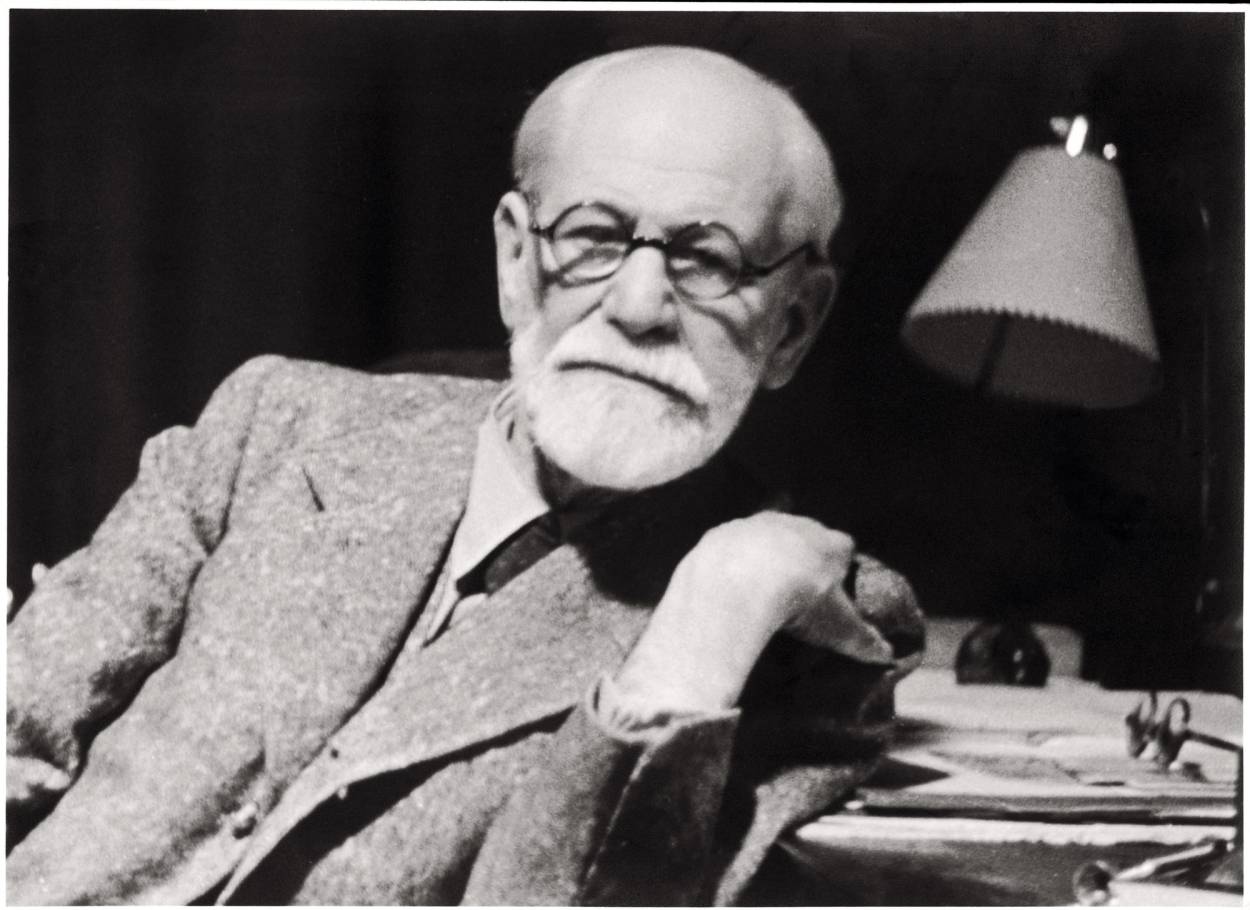

Last week when a Friend-of-Tablet reminded us that Sigmund Freud’s birthday was fast approaching, he urged us to pay tribute to one of the most influential figures in history, Jewish history, and romantic comedies. This is, of course, a near-impossible task, but since Freud’s birthday this year (this past Monday) was painstakingly close to another big celebration (Mother’s Day), I thought a better question to ask would be: What would Freud say about Mother’s Day?

To help, I enlisted Daphne Merkin, who in addition to being a Tablet contributor and a celebrated writer and critic, knows more than a thing or two about Freud and the intellectual domains in which he dwelled.

The first thing she pointed out was that Freud famously missed his own mother’s funeral for “unclear reasons,” an idea she coupled with his dislike for America based on his one visit there. She guessed that Freud would have dismissed the holiday as “American mishegas” and would have likely pounced on the holiday for its “false piety.”

She offered that in Freud’s view “the mother is a demeaned figure” and that the idea that we should “prop her up a for day” would be considered some kind of “collective delusion.” After all, Freud was a man who cherished nuance. “One can’t say Mother’s Day is a nuanced phenomenon,” she added.

We pondered whether other cultures have Mother’s Day–which they do, but not, we agreed, with the same specific American forcefulness.

“So by that way saying ‘an American mishegas’ seems accurate. A particularly externally oriented, commodified–not that the word “commodified” was bandied about in his day–way of declaring a sort of unitary affection. To me, Mother’s Day is the sort of the cheerful or the blithe apogee of the unexamined life. It seems like the Macy’s Day Parade, it goes about as deep as that. It does well for all the florists across the country and I suppose the balloons do well at that time of year, but basically, I think he would have seen it as a mandated, compulsory rite rather than a real expression of anything. That’s what I think, keeping in mind that he seriously missed his mother’s funeral.

I don’t think he was someone with much use for idealized positions, for idealized attitudes. The heart of psychoanalysis is sort of like a tolerance or ambivalence for the dark and the light and he was fairly dark so I’m saying this is sort of an occasion that says ‘Out, out!’”

I am sure there might be some disagreements among the Freud experts and Mother’s Day enthusiasts out there and I look forward to reading them. But in the meantime, if you find this interpretation of Freud to be cold-blooded, maybe consider these lines of W.H. Auden’s, who called Freud “an important Jew who died in exile,” in a poem Auden dedicated to him:

But he wishes us more than this. To be free

is often to be lonely. He would unite

the unequal moieties fractured

by our own well-meaning sense of justice,

would restore to the larger the wit and will

the smaller possesses but can only use

for arid disputes, would give back to

the son the mother’s richness of feeling…

A curious thing here is that Freud’s exile was Auden’s homeland of England, where Freud went to escape Vienna as Hitler’s forces closed in. (Freud’s four older sisters did not escape.) Freud was saved, in large part, by an odd collection of supporters, among them Anton Sauerwald, a chemist with Nazi ties who respected Freud enough to help him get out, and the French Princess Marie Bonaparte who provided crucial financial support .

What does any of this have to do with Mother’s Day? I’m not sure and I don’t know why you’re asking. How does that make you feel?

Adam Chandler was previously a staff writer at Tablet. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Atlantic, Slate, Esquire, New York, and elsewhere. He tweets @allmychandler.