‘Ex-Frum’ vs. ‘Datlash:’ Two Very Different Literary Genres

How a Hebrew acronym gives formerly religious Israeli writers more freedom

“Datlash?” I ask the young man sitting next to me at an Ein Prat pre-army leadership program in Kfar Adumim, outside Jerusalem.

“Dati le’she’avar,” he tells me, “Someone who was religious in the past.” No one seems to know the exact origins of the acronym or when it first began to be used, but it’s a stark contrast from the moniker ‘ex-frum,’ the closest corresponding English descriptor. The Hebrew term is more elegant, implying more a complex spectrum than a clean break. Perhaps that’s because there is no such thing here in Israel—without leaving the country, at least—as being ‘ex’ anything.

Three works, all recently translated into English, written by Israeli writers who are no longer as observant as their families, highlight the potential for more fluid identities outside the distinctly American frum/ex-frum dichotomy.

Dov Elbaum, the youngest of nine children from a haredi home in Jerusalem, wrote a spiritual autobiography in 2007 called Into The Fullness of the Void. After he left the Orthoodox community, his father asked a prominent rabbi whether he should sit shiva for his son. He was told not to, but he still didn’t speak to his son for the next 10 years. Elbaum, who says he remains a religious person within a more liberal framework, started the secular yeshiva BINA in Tel Aviv and hosted a weekly television program about the Torah portion for many years. Leaving the religion of his youth did not mean leaving religion altogether, he explained, but instead meant finding a way to express his identity outside the rigid framework of his haredi youth.

Dror Burstein’s remarkable novel/essay/metaphysical reflection, Netanya, is a book where past and present come together, at once telling the story of his grandfather while also incorporating his own experiences attending a religious high school that stifled his interest in science and astronomy. The religion of his grandfather, a cantor in his synagogue, pervades Burstein’s descriptions of his own childhood.

Sunburnt Faces is a coming-of-age novel about a girl from a religious Moroccan home in Netivot, in the south of Israel, who becomes a writer of children’s books. The book opens with protagonist Ori Elhayani having a religious revelation sparked by a voice coming from an entirely modern apparatus, whose message she doesn’t understand. The protagonist’s story concludes with a wonderful series of parables that the character has written to help understand her revelation—literature itself becoming a form of sacred text. The writer, Shimon Adaf, who won Israel’s highest literary award the Sapir prize in 2013 for the fifth of his six novels, grew up in a religious Moroccan home and now considers himself wholly secular, though he regularly spends Shabbat and Jewish holidays with his religious family.

Each of these writers has moved away from the religious community of his or her youth, embracing a different relationship to tradition. Still, they all live in Israel, and, for the most part, continue to have close relationships with their families. Their goal seems not to be to obscure or get rid of the past, but instead to use it to inform the present. It’s a different approach, and one which, in these instances, involves less anger and frustration than what we’ve seen in the recent spate of “ex-frum” memoirs on shelves in the United States.

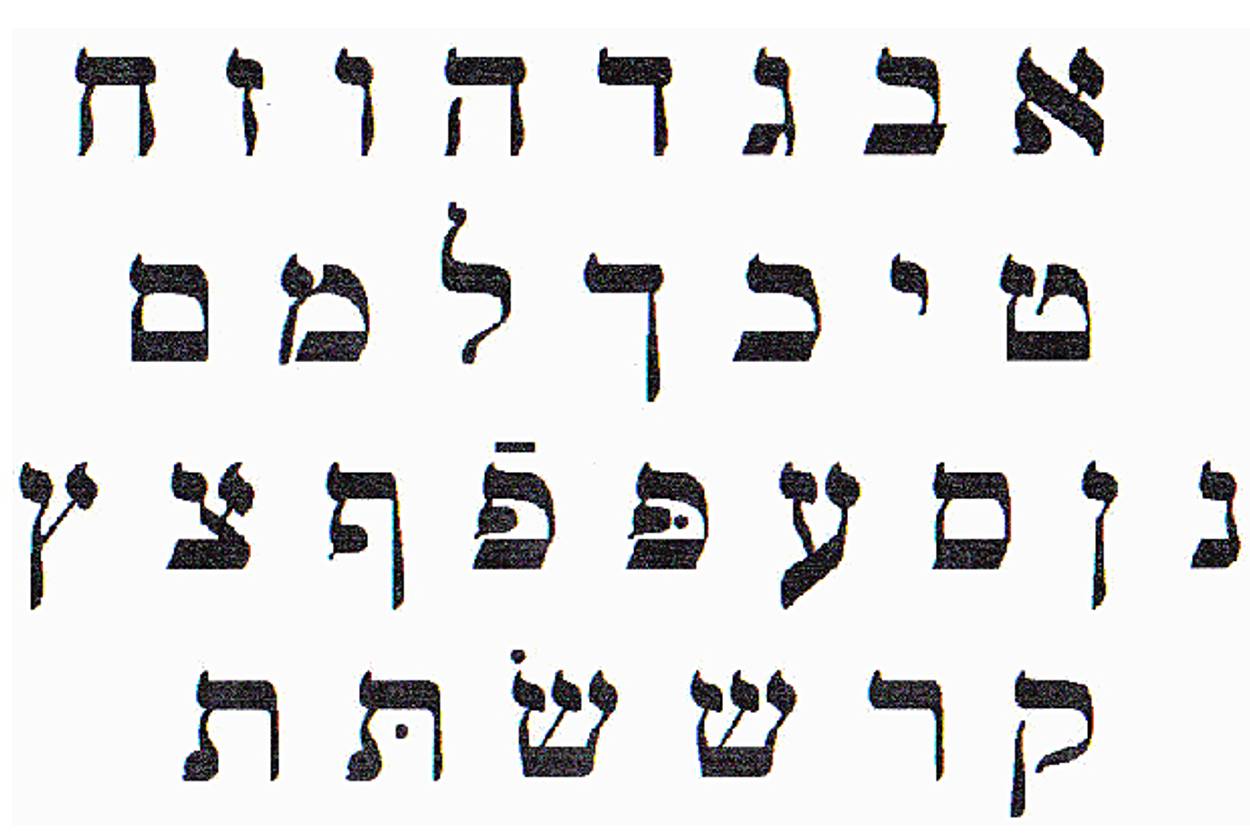

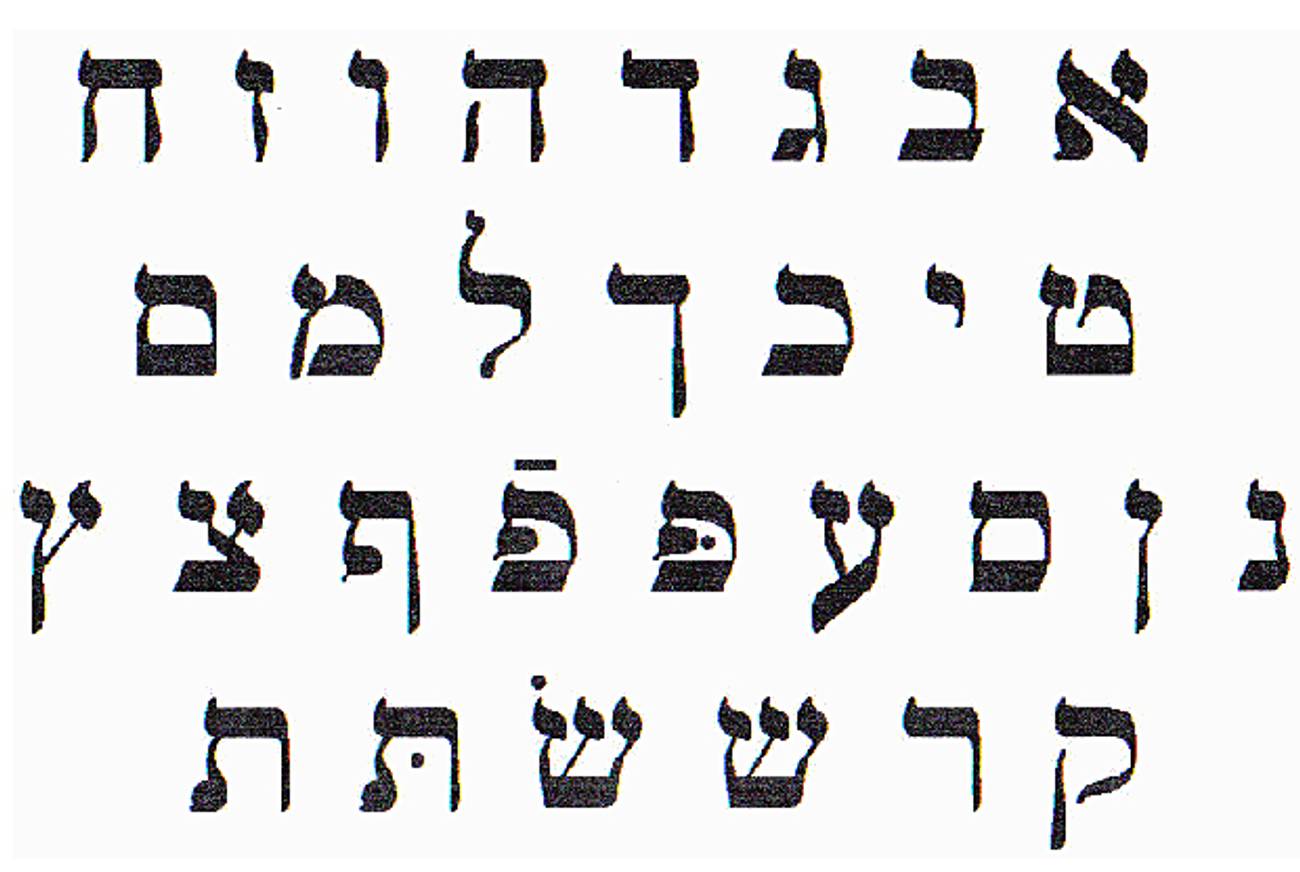

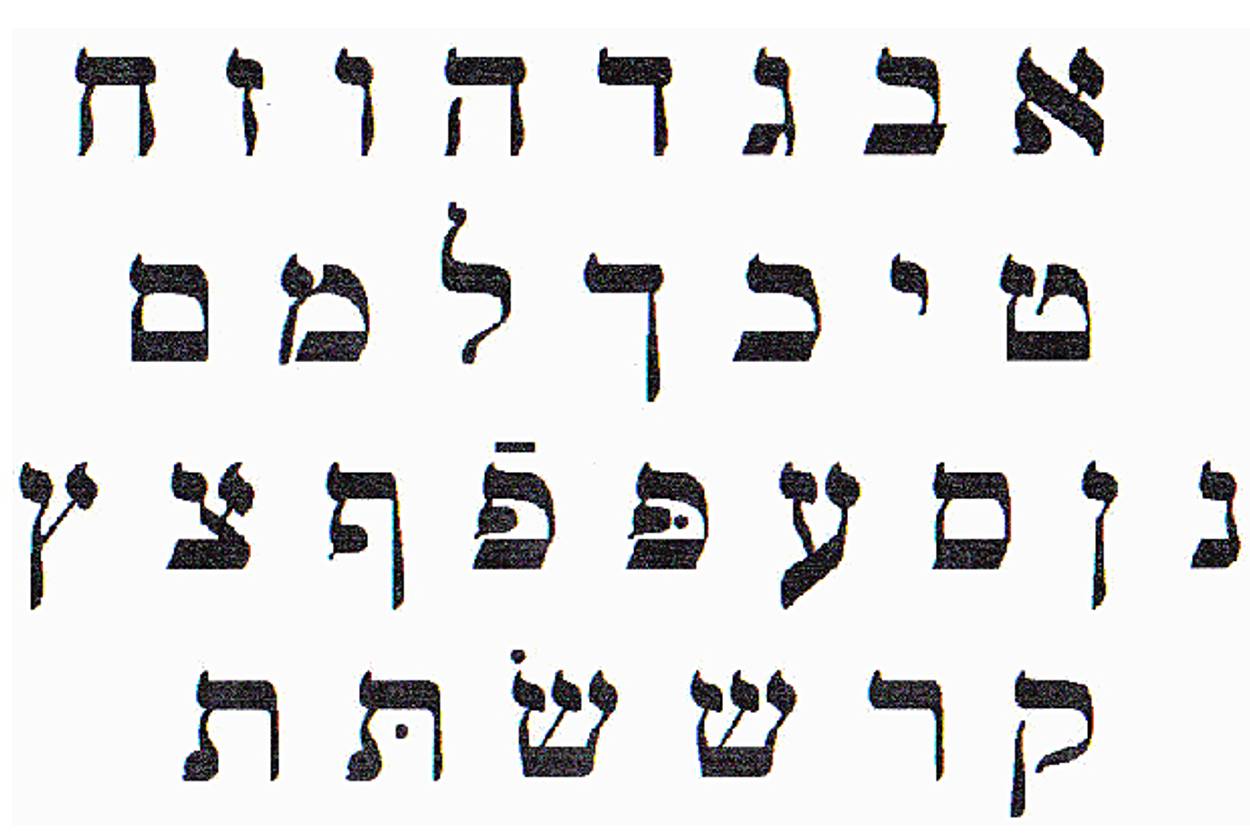

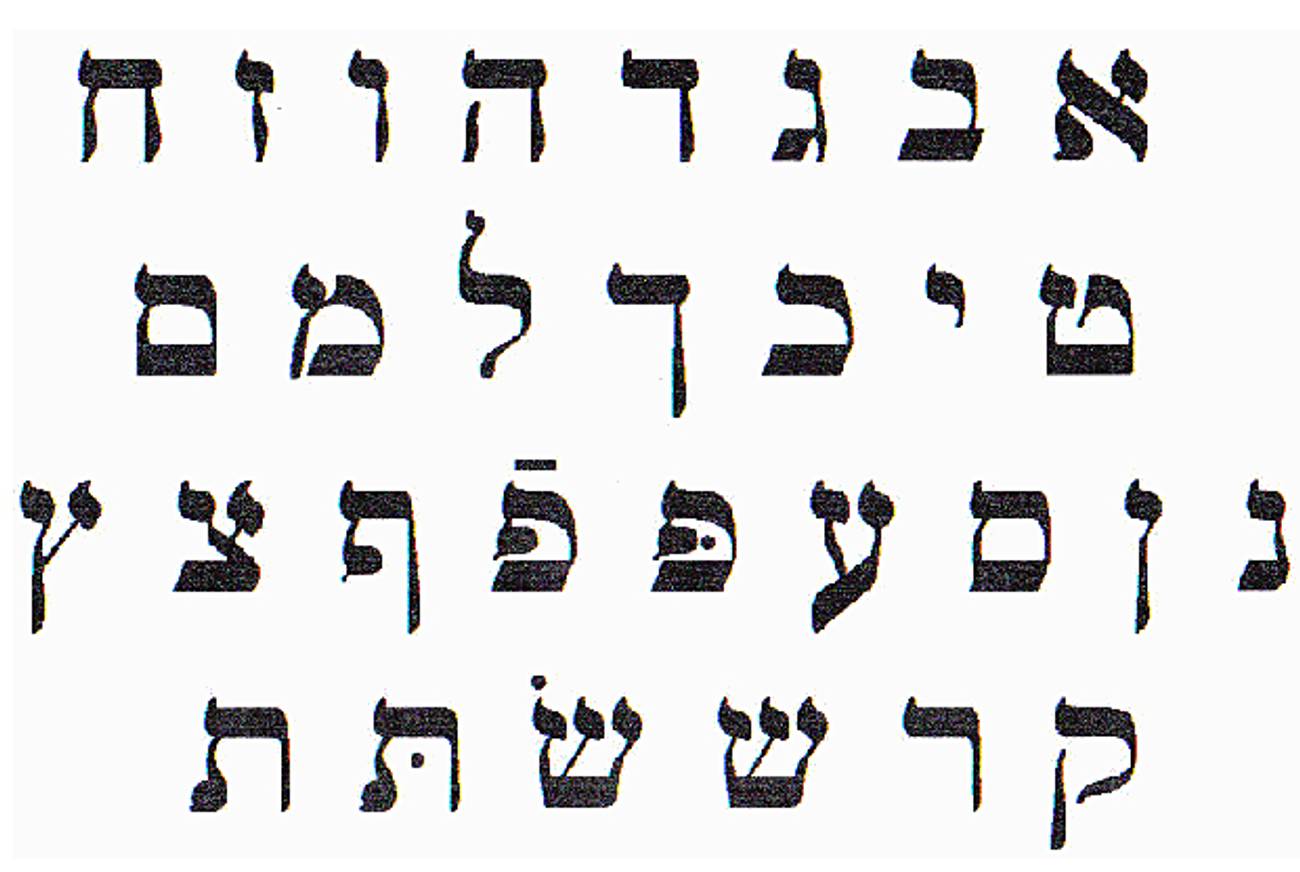

I love the Hebrew language’s ability to use acronyms like datlash to neatly encapsulate a complicated identity into one word, and I wonder how English could similarly expand to effectively communicate one’s past in the present tense. “Returnee to the question” (as opposed to baal teshuva, for those who become more religious as adults than they were as children) is too formal for my taste; the Yiddish term frei, for “free of the commandmants,” feels too limited. “Past religious” echoes a famous modern Hebrew novel, Past Continuous, by Yakov Shabtai, and perhaps because of that works best.

I still prefer the term datlash, though, and am fascinated by the literature it has produced so far. It’s not so different from an earlier generation of Hebrew literature produced by writers who left the yeshiva world for the literary one. Maybe it’s this sense of building on what has come before in Hebrew literature, rather than tearing down the world one has come out of, that best describes the difference between the works of ex-frum writers in English and datlash in Hebrew.

Beth Kissileff is the editor of the anthology Reading Genesis (Continuum, 2016) and the author of the novelQuestioning Return (Mandel Vilar Press, 2016). Visit her online at www.bethkissileff.com.