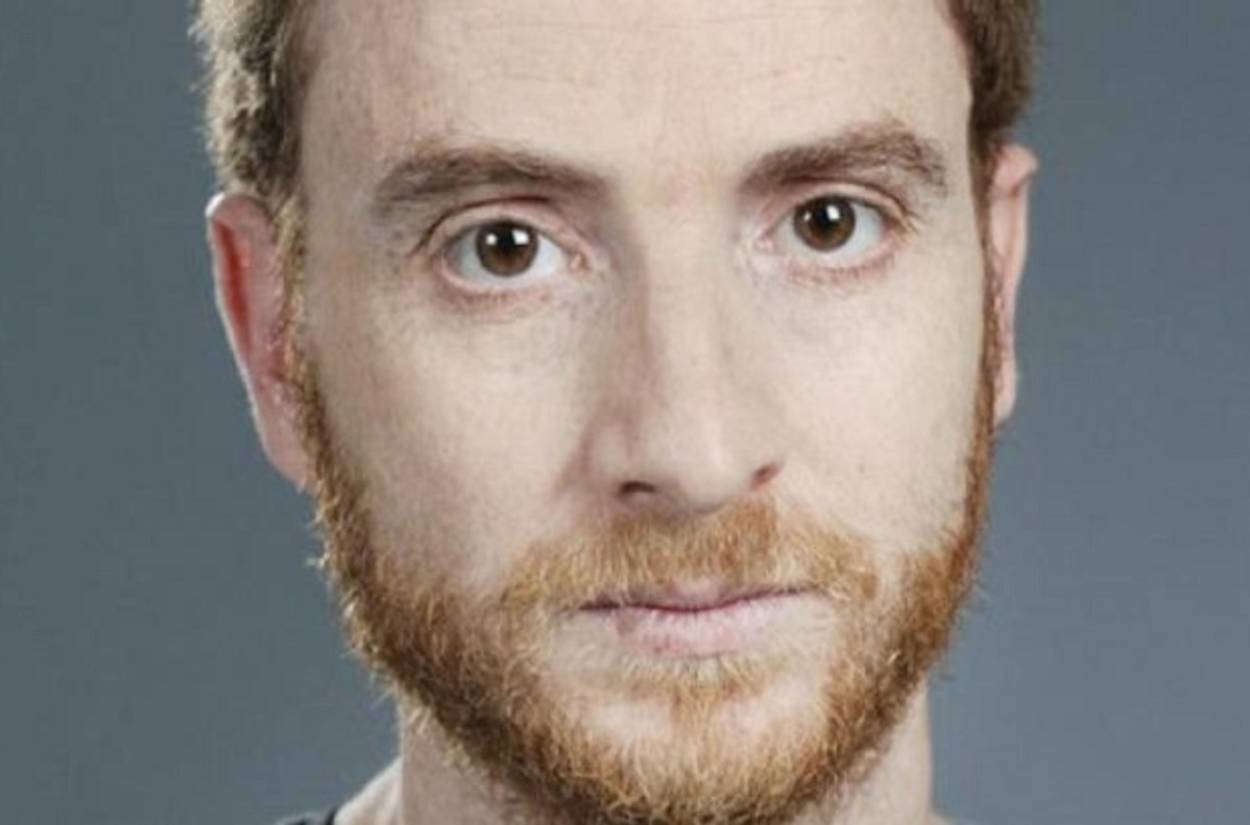

Is Shimon Adaf Israel’s Next Literary Luminary?

Acclaimed alongside Stephen King and Margaret Atwood, his work comes to America

Gan Meir is the oldest public park in Tel Aviv; its central location has made it the starting point for Tel Aviv’s annual Gay Pride parade as well as home to a dog run and a water-lily pond. Gan Meir is important not only for the rare green space for families it provides in the bustling city, but also, now, for how it is used in the private imaginings of Shimon Adaf, the 42-year-old Israeli writer of six novels and three books of poetry. Adaf, who is also head of the creative writing program at Ben Gurion University in Beersheva, is the 2013 winner of Israel’s prestigious Sapir Prize for his novel Mox Nox. Gan Meir is part of the Tel Aviv setting for Adaf’s third novel, Sunburnt Faces (2008), his first to be newly translated into English by Margalit Rodgers and Anthony Berris—a coming-of-age story with fantastical elements whose opening section occurs in Netivot, in the south of Israel. Though he is a popular literary figure in Israel, he is not yet well known outside of the realm of Hebrew readers. Now, with Sunburnt Faces—and Mox Nox slated for translation next—Adaf’s unique take on modern Jewishness should deservedly reach a wider audience.

By email, Adaf suggested Gan Meir as the best meeting place for a first stop on a Sunburnt Faces tour of Tel Aviv. We sat on chairs in the sun in the park. There, he told me, the books’ protagonist experiences “some kind of revelation.” She doesn’t understand the nature of her revelation and needs to go try to “bridge this gap between the world and texts.” The revelation confuses her. She is trying not to find answers—because there are no answers—but instead to “find the error … to try to build her life around an error she can live with.”

At the time of the novel’s writing, Adaf was living in an apartment on nearby Trumpeldor Street, overlooking the park. Adaf gives Ori Elhayani, the novel’s protagonist, the same view and location for her fictional Tel Aviv apartment. (She is also a writer.) As we walked to a real restaurant for lunch, Adaf showed me where he had imagined a fictional used bookstore for his book, based loosely on Halper’s Books, where Adaf once worked. In Sunburnt Faces, the physical resemblance of the owner to A.B. Yehoshua gives Ori the idea for her own first book, Double Dopplegangers. She is curious about why “two mirror images of him were wandering, one biological and the other imagined and random.”

The many biographical similarities are tricky. Ori, like Adaf, loves shakshouka, which he ordered at lunch, partly because it is a dish that reminds both him and his character of their Moroccan family origins. The character and her young daughter Alma also delight in a fictional version of the Max Brenner chocolate store on trendy Sderot Rothchild, rendered as Café Migdanot in the novel. But the novel diverges from the realm of common experiences of parks and cafes. Before Ori’s bat mitzvah, in the middle of the night, the heroine is given a divine revelation from her TV set, blank and empty in the middle of the night in the pre-cable era. Her inability to cope with this prophetic voice renders her mute for some time. In the second part of the book, Ori, now 32, is living in Tel Aviv with her daughter and husband: She has just published her third novel for children, A Map for Getting Lost. The plot of the book the adult Ori has written is about a girl who receives “a map to getting lost in a city she thought she knew.” As she uses it, she finds, “you get lost in one city and find another, a dark and perilous city filled with ghosts and wizards, vibrant with a secret history.”

This sense of looking beyond the limits of the physical world, into the realm of the fantastic, is central to the work of Adaf, some of whose writing is classified as Science Fiction, which Adaf called “the most important genre of the 20th century.” “I’m influenced by the works of many authors that came out as Sci-Fi,” he told me. “But I can’t say that I’m a Sci-Fi writer more than I can say I’m a poet or a literary writer.” Still, Adaf has recently appeared on The Guardian’s list of best science fiction for 2013, alongside Stephen King and Margaret Atwood. And last fall, at the launch of the British edition of Sunburnt Faces, he joined the British writer Neil Gaiman on a panel at a World Fantasy Convention. It has perhaps become a commonplace to suggest that the oddity (and technological futurism) of everyday life in Israel has resulted in the recent burst of quality science fiction. But Adaf’s writing straddles the line that separates the genre from straight literary fiction through his sensitivity to language from his first vocation as a poet.

Adaf is from the town of Sderot in the south of Israel, a place known almost as well for the rockets it has received from nearby Gaza, as for its burgeoning music scene. Adaf, a guitarist and singer, is part of the scene: He has performed with the band Ha’Atzulah, and has written lyrics for Knesiyat HaSekhel, which performed at last year’s Sapir Prize ceremony. As he has discussed in other interviews, when writing Sunburnt Faces, he chose a song to listen to and did that until he got an image in his mind of what his characters were going to do next. The idea, he said, came from the I Ching process used by writer Philip K. Dick, whose 1962 fantasy of Fascism rampantThe Man in the High Castle Adaf translated into Hebrew in 2012.

Beth Kissileff is the editor of the anthology Reading Genesis (Continuum, 2016) and the author of the novelQuestioning Return (Mandel Vilar Press, 2016). Visit her online at www.bethkissileff.com.