One Last Accused Nazi—in Queens

Jakiw Palij, a former guard at the Trawniki concentration camp, immigrated to the U.S. in 1949 as a refugee of war. Now 92, he lives in Queens and is believed to be the last ex-Nazi living in the U.S.

Last week, CNN published a story about Eli Rosenbaum, dubbed the “Nazi hunter,” who’s the director of Human Rights Enforcement Strategy and Policy. During the course of his career, Rosenbaum has led the U.S. government in the pursuit of “137 cases, of which 107 were successful in stripping citizenship or deporting accused Nazis.”

In the Nazi cases, a handful of attorneys, historians and researchers looked into as many as 70,000 names of possible Nazis. Their obstacles were many: they had to rely on a scant supply of documents, some held by authorities in the Soviet Union and countries behind the Iron Curtain. The suspects worked hard to hide their identities. Some snuck into the U.S. as refugees, and all denied any role in atrocities. Witnesses were few, particularly in cases like Trawniki, where Nazis wiped out entire populations.

“It’s very much a search for the proverbial needle in a haystack,” Rosenbaum said, referring to many of the cases that have gone cold given that they occurred decades ago. He’s inspired by his father, who once described his military service at Dachau to Rosenbaum while growing up on Long Island in the 1970s “when the term “Holocaust” wasn’t even common parlance.”

“That was a time when you just didn’t see your dad cry,” Rosenbaum told CNN.

But there is one remaining Nazi in the U.S., named Jakiw Palij, a former guard at Trawniki and Treblinka concentration camps who immigrated to the U.S. in 1949 at the age of 26. ”I spent five years in a refugee camp in Germany, and I had nowhere else to go but America,” he told the New York Times in 2003.

He’s now 92 years old and lives in Queens, NY. Palij’s presence is not a secret, and people have protested outside of his home for the better part of a decade. On the 75th anniversary of Kristallnacht, in 2013, demonstrators rallied outside the home of the ex-Nazi, screaming “put him on a boat!” and other derogatory statement.

“I’m starting to get used to it,” Palij told the New York Post, adding the he does not hate Jews and in fact has denied any wrongdoing, “claiming that he and other young men in his Polish hometown [of Piadyki] were coerced into working for the Nazi occupiers,” CNN reported. In 2003 he told the New York Times that he enters his home via an alley behind it.

Palij shuffled to his door on Sunday morning in blue Ralph Lauren PJs to give The Post a sob story that he was forced into Nazi servitude — and claimed he doesn’t hate Jews.

He said the German Army was rounding up teen-aged boys as it swept through Poland.

“They told us we would be picking up mines. But that was a lie,” said Palij “In that camp they took us — 17-, 18-, 19-year-old boys. I am one of them. They did not give us Nazi uniforms. They gave us guard uniforms: pants, black; shirts, light brown; and hats with one button in the front. You could tell we were not Nazis.

In 2004, a judge tried to deport Palij, but Europe would not take him, so he remains in Jackson Heights where he will likely live out the remainder of his life.

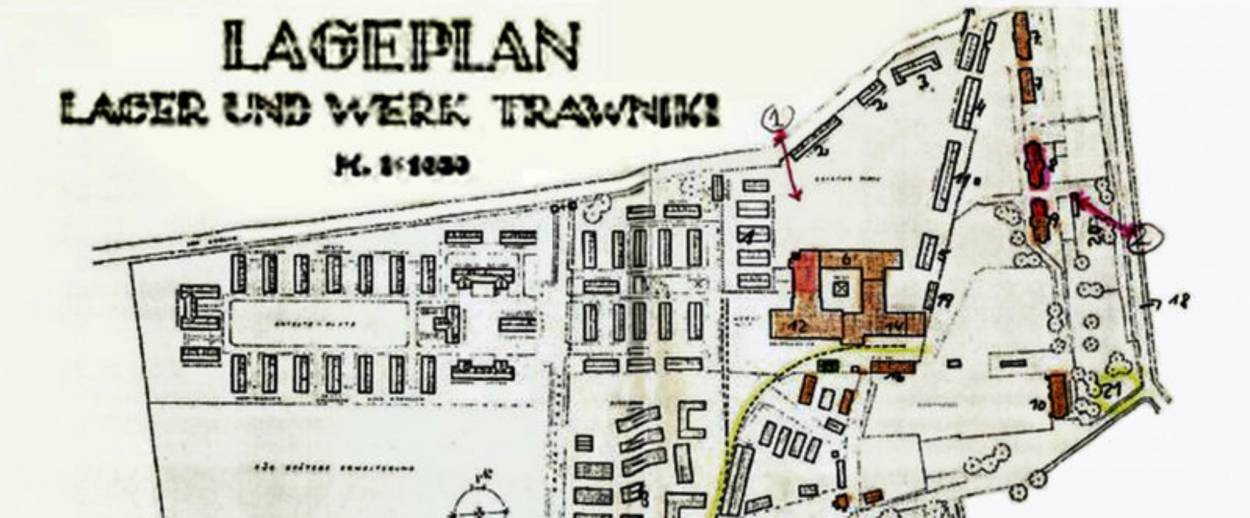

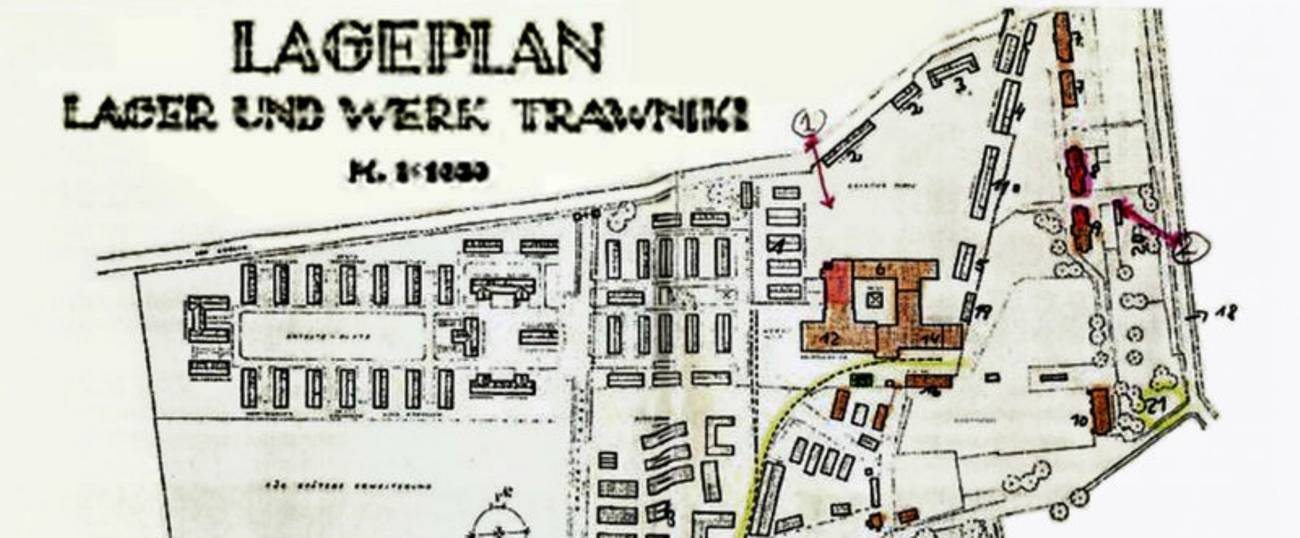

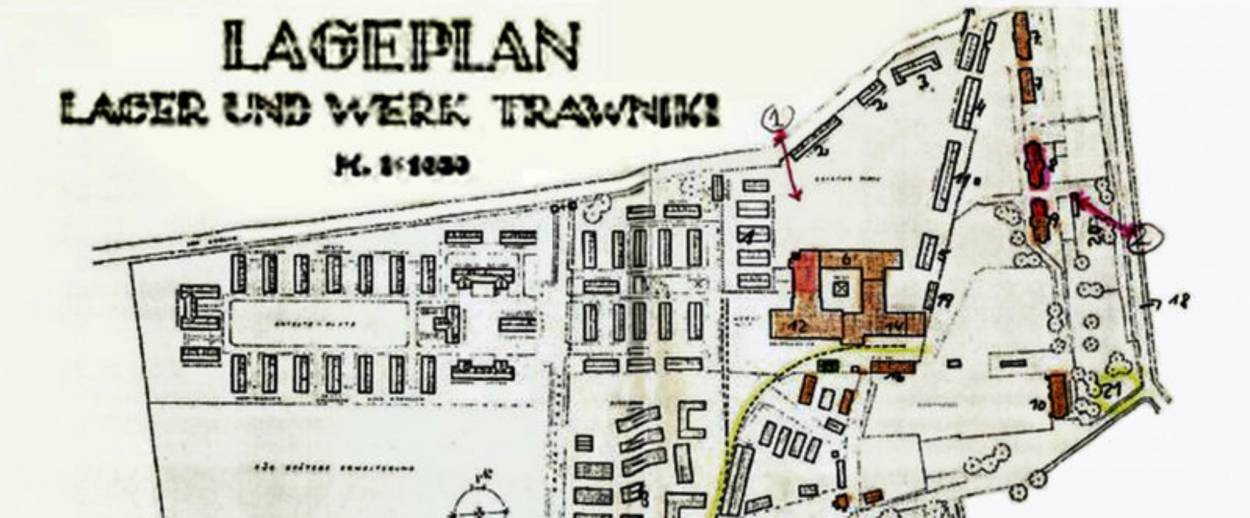

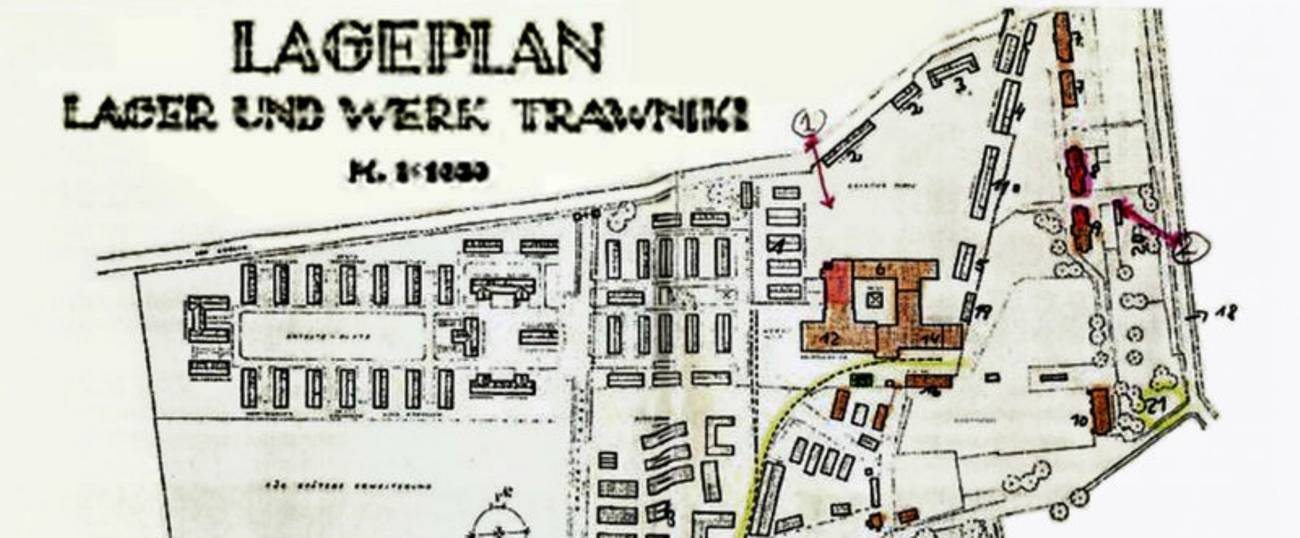

The atrocities of the Trawniki camp, where Palij worked, aren’t well known in part because the killing was thorough, historians say. One document researchers uncovered helped illustrate the extent of the killing. A soldier broke the butt of his rifle, which meant he was required to file a report so the German SS would issue him a new one. The report mentioned an operation that killed 4,000 people at Trawniki, mostly Jews.

The irony for lawyers and researchers working on the cases was that after stitching together evidence that someone was involved in atrocities, the most U.S. law would allow them to do is to deport former Nazis. Trying them for the actual crimes against humanity is something that was left for authorities in other countries.

”These Jewish groups want to hunt down all the living Nazis, and I don’t blame them,” said Palij in 2003, ”but they know I never worked in a camp. They have proof of that.”

Previous: Former Nazi Oskar Groening, 94, Convicted of Accessory to Murder

Related: The Doctor and the Nazis

Jonathan Zalman is a writer and teacher based in Brooklyn.