A Deep Look at the ‘Sickness’ of the British Left

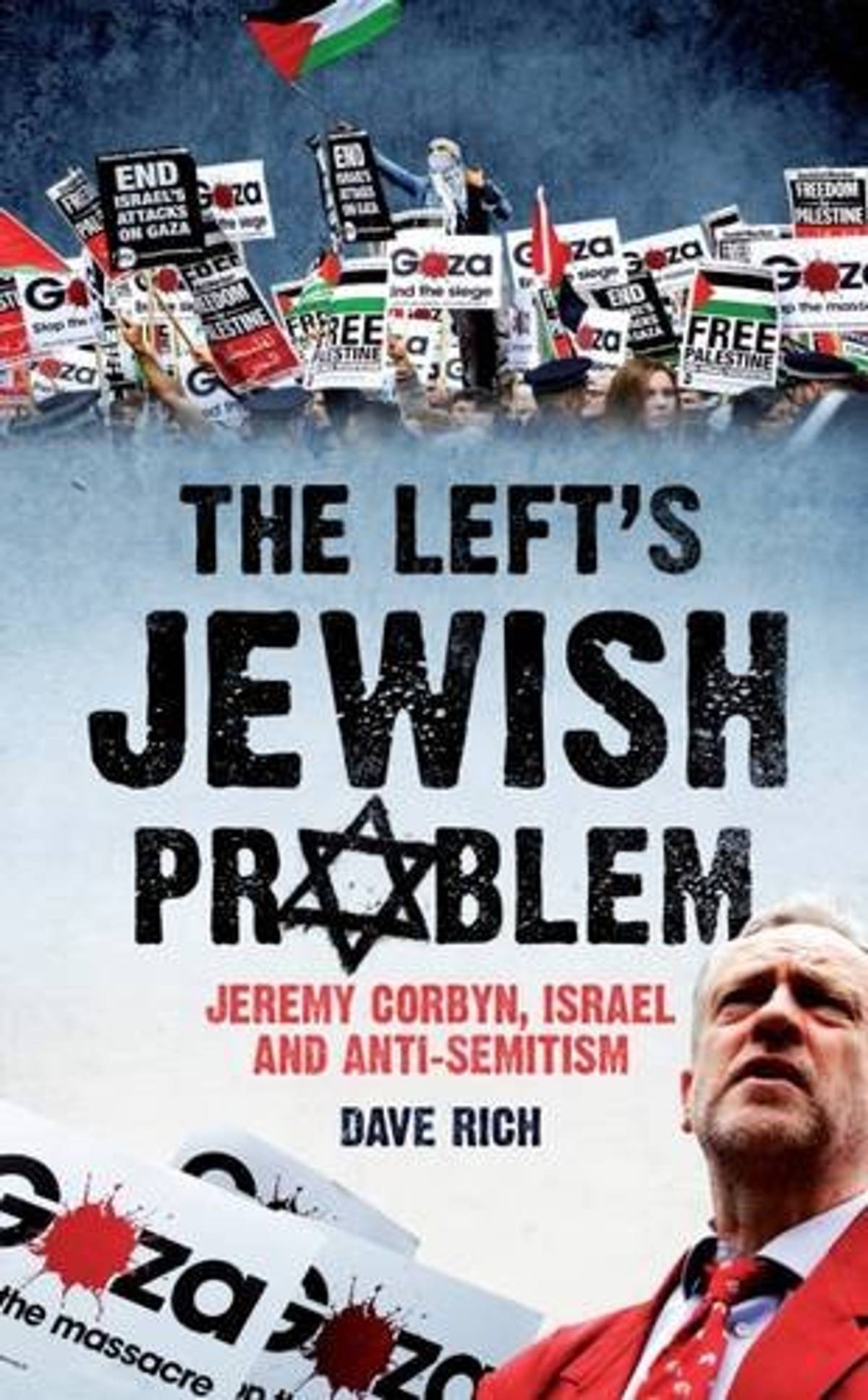

A review of ‘The Left’s Jewish Problem,’ Dave Rich’s new book, which explores the rise of British leader Jeremy Corbyn, and left-wing attitudes towards Jews and Israel

On the modern left, hostility towards Israel goes hand in hand with anti-capitalism, LGBT rights, and environmentalism. But it need not be this way. Nor, historically, has it always been this way. In The Left’s Jewish Problem: Jeremy Corbyn, Israel and Anti-Semitism, Dave Rich tells the story of how activists forced the question of Palestine onto the British agenda, how this cultivated a culture of hostility on the left towards Jews (by effect or design), and thus how it came to be that in 2015, the Labour Party elected a leader, Jeremy Corbyn, who considers Hamas “an organization…dedicated [to] long-term peace and social justice and political justice.”

Rich, a senior figure in the British Jewish community’s main anti-Semitism watchdog CST, introduces some history that might surprise readers. He traces the roots of the left-wing critique of Israel to before the Six Day War, when Egypt and the PLO already presented Israel through the lens of “Third World forms of Marxism,” as an innately imperialist project. He shows how this paradigm was picked up by “radical anti-colonial” activists in the youth wing of the UK Liberal Party, transmogrifying through the “more activist, militant and confrontational” version of the New Left from the late 1960s into a dominant strand in student politics—and often with funding from Arab regimes. And he shows how this worldview built alliances with Islamists, found a home in the Labour Party, and ultimately seized the mantle of the party itself by winning the broader battle to define the left.

By proudly parading its “anti-racist” bona fides while considering it an “article of faith…that Zionism is a racist ideology,” Rich argues that the modern left is unable to recognize anti-Semitism as anything but a right-wing phenomenon, and is thus unable to identify it within—and treats with contempt allegations of its existence.

Rich also gives a thorough history of the shameful period in the 1970s when student unions attempted to ban or curtail Jewish societies. In 1974, the National Union of Students adopted a “no platform” policy for racists. In 1975, the United Nations General Assembly recognized Zionism as a form of racism. Together, this led to numerous attempts to suspend university Jewish clubs for refusing to denounce Israel, since “Zionism is inherently racist.” This alone lends the book to an American audience, offering salutary lessons of where ostensibly anti-racist campus activism against Israel can lead, and how Jewish students can adopt the language of identity politics and build alliances to rebuff it.

Rich argues boldly that the left’s problem is not with “rotten apples,” but with the barrel itself. But he is disappointingly hesitant in his conclusions. Is Jeremy Corbyn an anti-Semite? It is unclear. At various points In the book, one can interpret Corbyn as a cognizant supporter of jihadist groups, a political operator who tolerates anti-Jewish prejudice as part of his vehicle to power, or simply a well-meaning fool with a blind spot for anti-Semitism; it is difficult to discern the precise charges.

Likewise, Rich remains noncommittal on whether “the idea that Zionism is a racist, colonialist ideology, and Israel an illegitimate remnant of Western colonialism” is itself anti-Semitic, despite tracing its origins in “overtly anti-Semitic” Soviet anti-Zionism. As such, it is unclear whether he diagnoses this worldview itself as constitutive of the “left’s Jewish problem,” or whether he is mainly concerned with the insensitive language and unsavory alliances through which it is expressed.

This agnosticism means that the book’s conclusion packs less of a punch than some of the well-researched analysis ought to justify. The recommendations concern how the rotten apples can change their behavior to “remove much of the tension and distrust” with Jews, rather than more serious introspection on the genesis and nature of these attitudes. Nevertheless, if one reads between the lines—as the author undoubtedly expects us to in such a potentially provocative work—the impression emerges of profound pessimism regarding the left’s ability to reform the rotten barrel, so to speak. There is no indication that the author, well acquainted with the British political scene from his work at the community security trust, expects this “sickness” to be cured, or even to be curable. And it is this uncomfortable realization at the end that gives the book its unspoken but disturbing kick.

Related: Jeremy Corbyn and the Two Lefts

Who Is Responsible for Anti-Semitism in the Labour Party? Jeremy Corbyn.

Eylon Aslan-Levy is an Israeli news anchor and political commentator. He is a graduate of Oxford, Cambridge and the IDF.