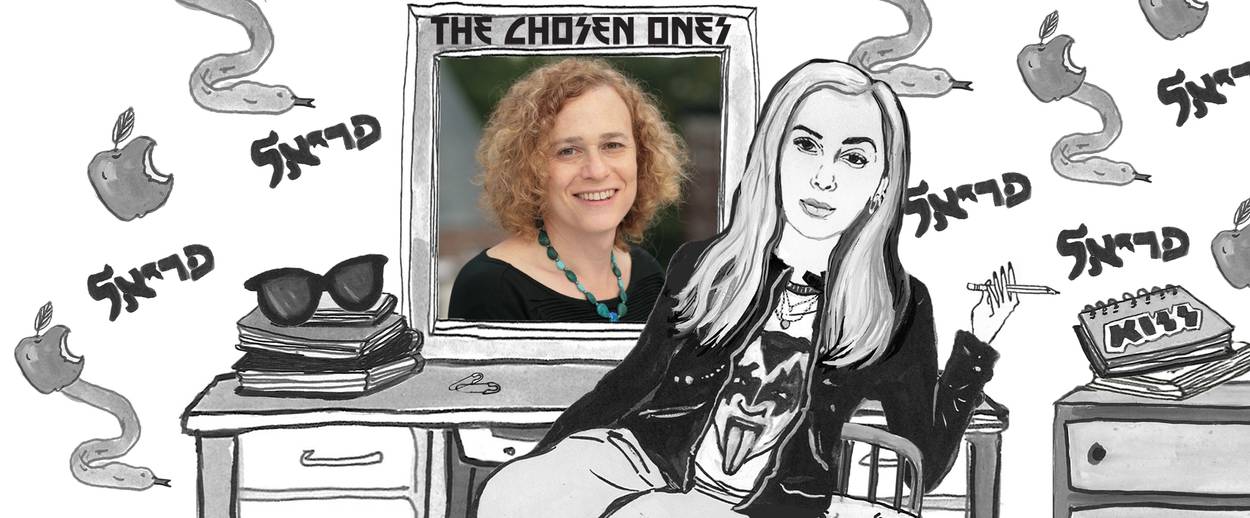

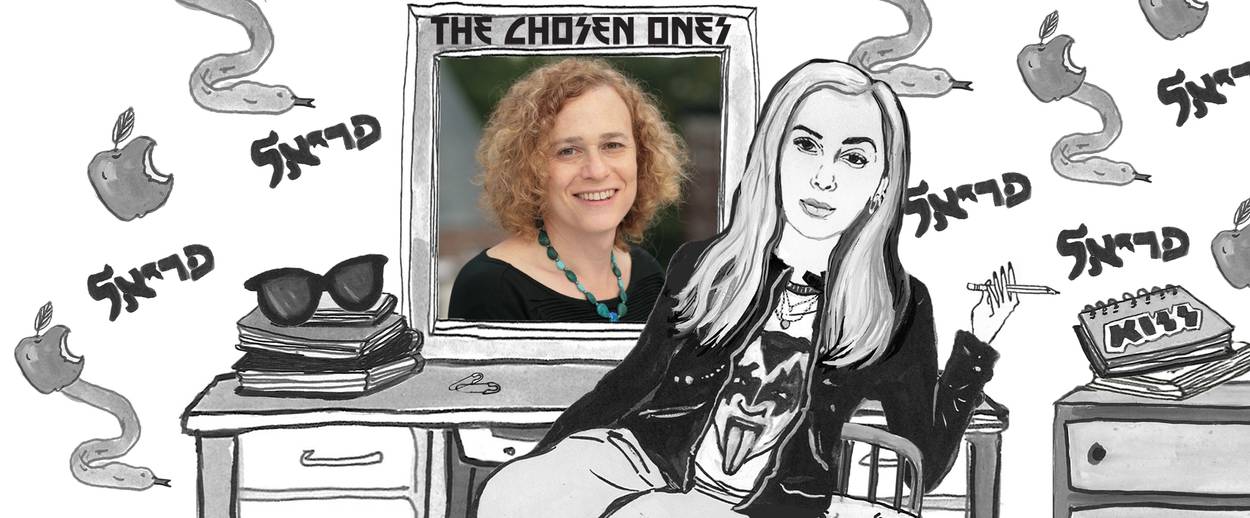

The Chosen Ones: An Interview With Joy Ladin

The writer and scholar on transgender issues in the Orthodox community, inclusion, and why Yom Kippur is her favorite Jewish holiday

The Chosen Ones is a weekly column by author and comedian Periel Aschenbrand, who interviews Jews doing fabulous things.

Joy Ladin is fancy.

She is the author of eight books, a finalist for both a National Jewish Book Award and a Lambda Literary Award, she was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts and a Hadassah Brandeis Institute Research fellowship. She holds a Ph.D. in American Literature from Princeton University, an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from the University of Massachusetts, and a B.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Since 2003, she has held the David and Ruth Gottesman Chair in English at Stern College of Yeshiva University. She has received a Fulbright and given a Tedx talk. Oh, and she’s also the first openly transgender professor at an Orthodox university.

Being a pioneer is by definition, not an easy job. And the Jews are a tough crowd—we’re anxiety ridden and nervous and, as a rule, we don’t love change, I think, because we’re always worried it’s just one more step back to the gas chamber. It’s not totally unwarranted fear, given our history, but what about when it’s the other way around? What about when it’s within our group that we need to be accepting and open-minded to things that make us uncomfortable, or are foreign to us?

Since November is transgender awareness month, I decided to reach out to Ladin—to discuss all of the above, and more.

Periel Aschenbrand: I would love for you to tell me about all the things the Jews are doing wrong. And also to tell you how wonderful it is to meet you and I think that what you’re doing is amazing.

Joy Ladin: Thank you. I like this premise but—

PA: It’s a long list, I’m sure. We’ll be here all night.

JL: I’m going to let Yom Kippur stand in for the long list of the things the Jews are doing wrong but I suspect you’re wondering about Jews and trans Jews.

PA: Yes.

JL: One thing I’ve noticed is that Jewish communities’ relation to gender, and whether they have a sense of gender that either tolerates or includes people who are not just male or female, is not a religious thing so much as a social thing. The Orthodox communities have a religious commitment to the gender binary. I actually know of an email discussion list of Orthodox trans Jews and so, informally, under the radar, there are a number of Orthodox communities that have trans members and those trans members are known to the local rabbis and sometimes to other members of the congregation and some of the rabbis even give the trans members Halakhic guidance. This is unprecedented, they teach them how to fulfill the mitzvot and it seems that most common formula is because of the principle of not disturbing the worship work of the community. So in public, you have to fulfill the mitzvot that go with your gender presentation but because Orthodox Judaism doesn’t really acknowledge such a thing as gender apart from sex, in private they say that G0d considers you, still, to be the sex that you were born as and so you have to observe those mitzvot when you’re in private.

PA: That’s very problematic.

JL: It is. But look at from another angle. They have invented non-binary gender, that is a form of gender that is neither male nor female, it has an idea of gender as performance. It’s like, how do you take a binary and performative idea of gender and mesh them together? That’s what they did in coming up with that. And what it really does is to try to use the language of binary gender to accommodate people who don’t fit it.

PA: But that’s very problematic.

JL: Well, yeah. It’s awful. It doesn’t identify people who don’t identify as male or female and it can be horrible for the people involved. But if you compare it to what you would imagine—I mean, you looked very surprised when I said there were trans Jews in the Orthodox communities.

PA: I’m not surprised that there are trans Jews living in Orthodox communities, I’m very surprised that there are trans Jews being embraced in Orthodox communities and who are allowed to be themselves. Which it sounds like they’re not, exactly.

JL: Well, yes and no. In private, nobody is monitoring you. They say halachically, in public, you are required to act as the gender you transitioned to.

PA: Well that’s a good thing.

JL: I think this is cutting edge.

PA: Yes, that’s amazing. And what about little kids?

JL: In secular society, we value newness so much that we even pretend that old things are new because we are only interested in new things. So you’ll see, every few years, something about the new monogamy or the new dating or the new kissing even though these things have been going on forever. But you can’t sell magazines by saying “people still date” so you put “new” on top of it. In traditional communities, it works exactly the opposite way, something being new is not good. So you pretend that new things are old. And as you accept them, you reframe them in ways that are traditional.

PA: I was intrigued to find out that there are these words—tumtum (a gender identity where a person’s sex characteristics are indeterminate or obscured) and ay’lonit (a person who is identified as “female” at birth but develops “male” characteristics at puberty and is infertile), and androgynous (a person who has both “male” and “female” sexual characteristics)—that go back to the Mishnah and the Talmud.

JL: It’s something that will be important to the Orthodox when they get around to accepting that tradition has always been something that has accommodated this. At the moment, it’s more important to trans Orthodox Jewish scholars who are looking for places in tradition. Those words are about bodies not about gender.

PA: OK, but trans people have been around since the beginning of time.

JL: But when we talk about trans people, we’re not talking about bodies, we’re talking about self-definition. What the rabbis were talking about was bodies. They’re not talking about how these people see themselves. For all we know, these people see themselves as either male or female or they see themselves as something else. I don’t know, maybe the rabbis didn’t care. There is no concept in Jewish tradition as “gender as apart from sex,” so it’s all reduced to sex.

PA: Just in Orthodox, you mean? In secular Judaism, certainly there is.

JL: That’s right. But in traditional Jewish texts, going back to the Torah and the Talmud, nobody talks about people whose bodies are one way and their understanding of themselves is another way. This is important because it recognizes that contrary to the way that people usually read Genesis. Humans beings are not just created male and female in the physical sense, but there are other ways a body can be and that the rabbis responded to that in the way these Orthodox rabbis are privately responding to trans Jews. Instead of saying, “You don’t fit the male/female thing, you can’t be part of the Jewish community”—they didn’t say that—they took the binary language of male and female and they stitched them together to fit this non-binary.

PA: And that’s the case now, too? So you’re saying there are places in Borough Park and God knows where else—say, in Monsey and Beit Shemesh—where they are embracing and allowing kids and adults to be themselves?

JL: I’m not aware of that. What we’re talking about is the religious, ideological approach to Judaism but what you just said has more to do with the social part of it.

PA: The religious, ideological part is important and interesting, but the thing that I am most interested in and, frankly, concerned about is how that translates to real people’s real lives, in Orthodox and secular Judaism. I want my son to be able to grow up in a world where people are allowed to be who they are. To say nothing of the physical danger and psychological trauma of it. As a Jew, and probably pretty obviously not a very religious one, I feel like this is something that is really important. And I’ve never heard it addressed in any reform or conservative synagogues. I certainly haven’t heard it talked about in Orthodox synagogues, not that I’ve spent very much time there.

JL: I’m glad you’re upset by it.

PA: I am upset by it!

JL: Most of it is not different for Jews than it is for anybody else so when I go around the world to most places, including very progressive places, it is just assumed without thinking that everybody is either male or female. When 90-plus percent of people are something, we always round up to a hundred, which is not true; there is rarely 100% of anything. But in the vast majority of communities, the vast majorities of people fit into these male and female categories. Most people find a way to do that because the social penalty is so strong. What that means is that communities don’t have any provisions for people who don’t fit into those categories. And Jewish communities are like that also. And that includes Reconstructionist communities, who have changed their welcome statements but haven’t actually thought about what it would be like to have a trans person.

PA: But most communities don’t show off about how important community is. That’s one of the things that is inherent in what we preach, as Jews—family, this, family that, community this, that, the other thing. This is, culturally, a very Jewish thing. I’m not saying that is totally specific to us and not important to other groups of people and that their cultures don’t espouse those views as well, but this is a very Jewish thing.

JL: Right. There is a Jewish commitment to community but what most of us mean—

PA: Is a community of people who are exactly the same as we are?

JL: That’s right. Or, what we we really mean is an accepted range of variation. Different communities have different ranges of variations. So when people traditionally think about community, they think about homogeneity, about people who are bonded together based on what they in common. It’s a newfangled concept to say, actually, community is aspirational.

PA: Yes!

JL: It’s like democracy.

PA: Yes! Yes! That’s what I’m talking about.

JL: So this is non-traditional. When you say, “Jews have a commitment to community,” you’re doing a little bit of a bait and switch here, because Jews have a commitment to a traditional idea of community.

PA: So it’s bullshit.

JL: It’s both. I don’t know that I’ve been in a Jewish community that has said there are Jews we don’t want in principle. But in practice, we’re just not making things easy for certain kinds of people. So we know the people we know and we deal with the variations within the people we consider ‘us’ and if you don’t fit ‘us’ then we don’t really deal with you. That’s the norm. That’s the background. But against that background, the interesting thing is the number of Jewish communities that have been trying to move to a different idea of community with regard to gender. So you have the movements that are not Orthodox that have made various degrees of policy change as movements. Of course, Jewish communities are not centralized, we’re not the Catholic Church so nobody really cares when the Conservative movement decides this, but it does represent that a group of people have been thinking about it. And they do want to include people who are not simply male or female and at policy level. People have done different degrees of thinking about it.

I just talked today to a rabbi—Rabbi Len Sharzer at The Jewish Theological Seminary—who is trying to change policy for trans people and trying to make provisions for nonbinary people.

PA: Good for him!

JL: He was a plastic surgeon before he was a rabbi.

PA: Of course he was.

JL: So he has a unique skill set in thinking about this.

PA: And he can give you a good nose job.

JL: Yes, that’s right.

PA: That’s very impressive. It shouldn’t be, but it is. Not the nose job part, the policy part.

JL: It is. So he’s not trans but he has these two commitments. One the one hand, he’s committed to conservative Judaism and on the other hand, he is committed to the idea that trans Jews are still Jews should have a place in the conservative community, which doesn’t mean let’s not beat them up and drive them out. It means we have to meet their needs and anticipate their needs.

PA: That’s right. We do.

JL: What do we do when they want to get married? What do we do when they want to use the mikvah? So that is a lot of thinking. Particularly, if you think of it terms of Jewish tradition and how everything works.

PA: I read about Trans Torah, which has all kinds of support for trans and genderqueer Jews, to help them claim their heritage, even blessings for transitioning and chest binding. This is so wonderful and so important. Is that what Rabbi Sharzer is doing?

JL: He is working on a very long document regarding policy that has to go to a committee and be presented to larger and larger groups. So somebody has to do the work of figuring it all out. It is unusual that somebody does that. What he’s doing is not something you’re seeing in other places.

PA: And how are they at the university? I don’t have to write about this if you don’t want. I know that unlike me, you have a real job.

JL: The university is at the same place that a lot of people are. When I was growing up, in Rochester, NY, there was a lot of stuff about race and tolerance. And there was a binary. You were either tolerant or you were not tolerant and the ideal was to be tolerant. Now that I’m a visible minority, I’m like, so how does this tolerance thing work and what is it? I’ve realized that there is a spectrum of responses that communities have to difference. At one end is genocide: if it’s different in this way, wipe it out. And we’re experienced with this both on the receiving end but also on the delivering end, like the Malachites. What?I You left the women and children? So, that’s one end of the spectrum.

At the other end of the spectrum is full inclusion, which is what you see with something like eye color. And between these two, there are a lot of different degrees. It’s better to say, “Kick them out,” that’s better than genocide. It’s better to say, “Harass them and abuse them but don’t kick them out.” That’s still moving toward inclusion. It’s like, we hate you and we’re going to make your lives miserable for being different but we’re not getting rid of you. Then, you move toward the middle and you get something like tolerance. It’s like saying. “You’re different in a way we don’t really understand and we’re not comfortable with, but we’re not going to do anything to you.” And the deal with tolerance is you can be here as long as we don’t have to think about or talk about your difference. The attitude of the dominant group is: you’re here. Problem solved. So you’re here. We’re not going to kill you, we’re not going to kick you out, but we also don’t really want to deal with you. We don’t want to think about you and we particularly don’t want to think about you in ways that make us rethink ourselves.

PA: Exactly.

JL: So that’s the tolerance I was taught to aspire to and that’s pretty much my situation. Individuals are different but the institution as a whole can’t say they are delighted to have gender diversity.

PA: Why can’t they say that?

JL: You can’t say the word transgender.

PA: Why not?!

JL: What I’ve learned about tolerance, is that it leads to denial. Because the premise of tolerance is that if you’re here and we’re not doing anything to you then the problem is solved. And we know that’s not true. That’s the beginning of the problem but that’s not the end of it and that’s when denial sets in and people get very upset when you puncture their denial.

PA: That’s enraging. And look, I’m not saying we haven’t come a long way, but we obviously have a long way to go.

JL: I agree. It’s a community by community thing. There are a lot of resources in Northen California but a lot of Jewish communities have other problems, too. They’re shrinking, they’re aging, they have an influx of young kids and they don’t have a good Hebrew School.

PA: That’s a big one, I’m sure. Let me ask you this: What’s been the most surprising wonderful thing you’ve discovered since coming out as trans?

JL: I’ve been blown away by how many Jewish communities have embraced me, having grown up the way that I grew up. I was born in 1961 in Rochester, NY, and I lived in hiding, in terror that anyone would find out that I was trans. I didn’t think there were other people like me and I wasn’t sure I was a person, and I was really isolated, and I was afraid and I did not think there could be any Jews or any Jewish community who could accept me for who I was. And tolerance was beyond my imagination, but the idea that there would be communities that would value hearing what I had to say was something I couldn’t even see in science fiction.

PA: Did you ever tell your family?

JL: No. No.

PA: You never told anyone?

JL: As I entered adolescence I tried to find a counselor, but nobody knew anything.

PA: The Internet’s been amazing, huh?

JL: It has. And there has been a lot of education from my perspective from where I have started. There are still a lot of places around the world that are exactly the same as it was where I grew up. They can’t imagine people who are not male or female. It’s not that they are hating people, but it’s that they can’t imagine it. Like in the Orthodox Jewish world, there is a fairly developed homophobia for gay men, there is a much less developed hatred of lesbians because people think about it a lot less. And nobody thinks about trans people enough to hate us.

PA: Oh, that’s just great.

JL: My assumption about the Jewish world was that no one like me is conceivable or could possibly be tolerated, much less valued, included or loved. So coming from that place, the life I’m living now is an unending series of miracles. The Jewish Book Council has been wonderful and I love that institution. Keshet works for ongoing inclusion and I know a lot of communities that I do a lot of different things so from my perspective, that is unimaginably good.

PA: Well that’s very nice to hear. We’ll end on a high note and I’m going to barrel through these next few questions. What’s your favorite drink?

Jl: I’m going to have to say coffee, if you want to just know what keeps me alive.

PA: How do you eat your eggs?

JL: Scrambled.

PA: How do you drink your coffee?

JL: Black and with as little interference as possible.

PA: What’s your favorite Jewish Holiday?

JL: Yom Kippur.

PA: Why?

JL: I really love the intensity of reflection and the intimacy with God. A holiday when you’re supposed to feel God looking at you is pretty great.

PA: Did you have a bar or bat mitzvah?

JL: I did.

PA: What did you wear?

JL: Damned if I know. I didn’t pay attention to anything I wore. I used to get dressed in the dark.

PA: Oh, that’s awful… What shampoo do you use?

JL: Whatever will keep my color from fading.

PA: Gefilte fish or lox?

JL: I hate cold fish. Which in my family basically disqualified you from being a Jew.

PA: Five things in your bag right now?

JL: Wallet, cell phone, vitamin C drops, a little notebook for writing poetry… there is tons of stuff in here. Oh, a nametag from the Lamda Literary Awards.

PA: Favorite pair of shoes?

JL: The ones that don’t hurt when I wear them.

PA: Who makes your necklace?

JL: I make my necklaces!

PA: It’s beautiful. So what’s your favorite thing to wear, now?

JL: My favorite outfit now is some combination of knee-length or longer skirt, black boots, a top with something going on with the neck, and a necklace, in greens, blues, and/or blacks. This shows you how limited my remedial fashion development has been!

PA: I think you look perfect!

Periel Aschenbrand, a comedian at heart, is the author of On My Kneesand The Only Bush I Trust Is My Own.