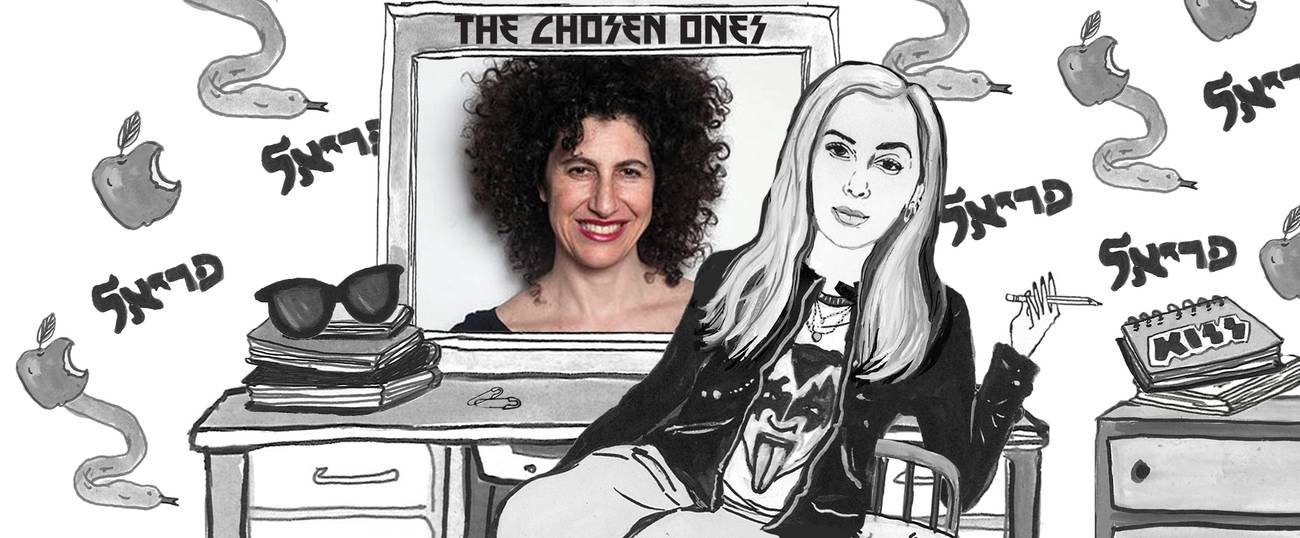

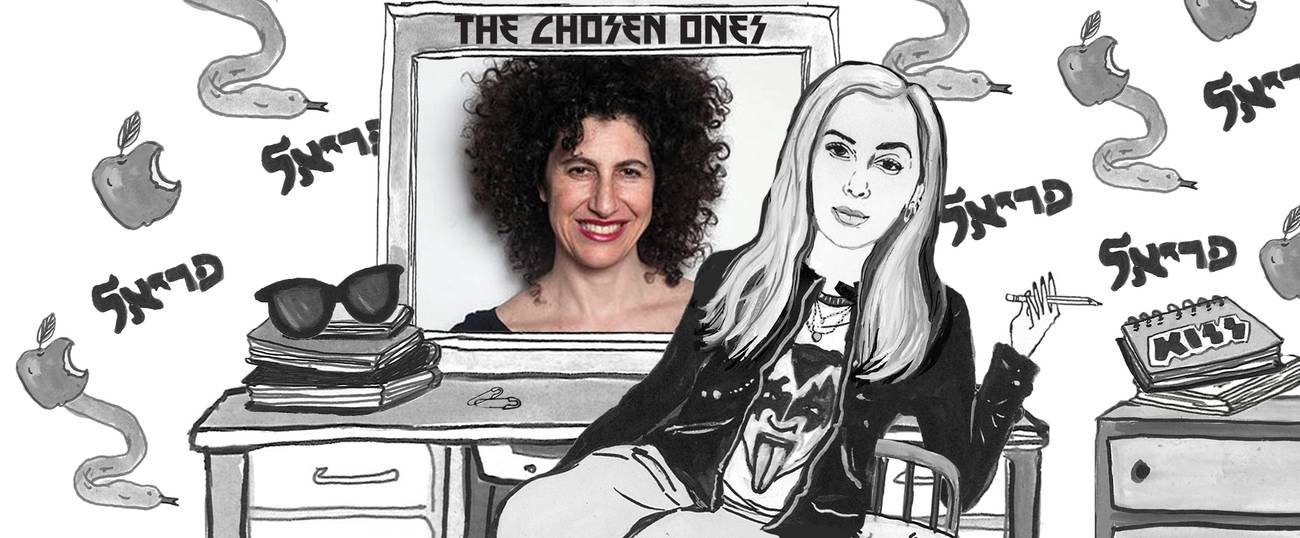

The Chosen Ones: An Interview With Jessica Mitrani

The Colombia-born artist and filmmaker on Hebrew school in Bogota, escaping to New York, and celebrating her ‘Jew ‘fro’

The story and rise of filmmaker and multimedia artist Jessica Mitrani is an unlikely one. Mitrani is a second-generation Colombian who grew up in a small Jewish and conservative community in Barranquilla. Even so, she was constantly questioned about her origins because of the way she looks. As a result, she has always been fascinated by identity.

Mitrani was a young mother, who became a family lawyer, who became an artist, and she moved to New York in 1999. She has since had work exhibited at the Centre Pompidou, Oaxaca and Marfa film festivals, The Hole gallery in New York, and MoMA PS1.

Her new exhibition, Traveling Lady, in which iconic Spanish actress Rossy de Palma “conjures the daring spirit of Nellie Bly, the nineteenth century American journalist who circled the globe in seventy two days, carrying little more than the clothes on her back and a jar of cold cream,” is currently on view in Miami until January 27.

Her work is brilliant, whimsical, smart, provocative, fun, and feminist as fuck. Which makes sense, because so is she. I recently caught up with her at her studio on Canal Street in lower Manhattan.

Periel Aschenbrand: What is this doll/conjoined twin sculpture?

Jessica Mitrani: This is Lupe. She is based on my first childhood doll, that I lost for a while. And then I told a friend and he was like, Lupe is mass produced and he took me to downtown Barranquilla and I got and made a mold of her and created this.

PA: For years you’d been devastated?

JM: For years. I was so attached to her and I didn’t play with Barbies and I remember that loss,

it was terrible.

PA: How old were you?

JM: I was like 5 years old. And when I see her, and I look at her, with her little boots, I understand. And I think she was my first, let’s say, object that made me think of identity. She’s this independent person, with her short hair, her hands in pockets, her boots. Androgynous. If you put her right now, in the East Village, she’ll blend in perfectly well. I think there was something in this doll that said, “Jessica, this is a possibility…”

PA: Wow.

JM: This, of course, I realized after a thousand years of psychoanalysis.

PA: No wonder you like psychoanalysis so much, look at how much it’s helped you! I love them!

JM: Thank you. I did a series and there are 12 of them. I made them for an exhibition called “Lupe and the Austrians” for an exhibition in Bogota. I decided to recreate her as an adult. Now that I’m an artist, I can do what I want. It took me a long time. My background is law. I’m an attorney and it took me a long time to assume that I was an artist and to even say the word artist.

PA: Let’s backtrack for a second.

JM: I was born and raised in Barranquilla. My father was born in Cartagena and his father came from Romania in the early 1930’s.

PA: Because of the war?

JM: Yes. He came with his brothers and sisters because they had relatives there, but I didn’t know much about it. No one talked about it. Then five years ago I find out that my great grandparents died walking. No one ever told me this information.

PA: The Nazis.

JM: Yes. And to hear this was so shocking.

PA: And where was your mother from?

JM: My mother’s parents are Sephardic Jews. There was a place called Trani in Southern Italy and there were a lot of Jewish people in Trani. And in Turkey there were many opportunities so everybody from Trani went to Turkey. And so everyone who went to Turkey were the Mitranis.

PA: No way!

JM: Yes! Exactly! And so my father is from Cartagena, the coast—a lot of African influence, drums, percussion, a lot of openness. And my mother is from Bogota, which is the capital—mountains, Andean, much more introverted culture. And they were never really connected to their Jewish side.

PA: So why’d you go to a Jewish school?

JM: Exactly! Because they didn’t feel very connected and didn’t know the history, so they decided to send us to the Hebrew school in Bogota. We moved there when I was six. So we went from the Jewish school to the Jewish club and the club to the school.

PA: And you were always the black sheep.

JM: Always. And I escaped to New York in 1999.

PA: So you came here as an attorney.

JM: Yes, I was a family lawyer. And I got married when I was nineteen. To my second cousin.

PA: Did you know he was your cousin?!

JM: Yeah. I mean, in a way all the Jews in Colombia are related. So it’s a matter of degree.

PA: Did you grow up together?

JM: No. But sort of. Second cousins are…

PA: Far.

JM: No. Close. Think about it, our grandfathers were brothers.

PA: Is that legal in most states? Just kidding. That doesn’t seem that close.

JM: Periel, it’s close.

PA: I have to spend a little more time thinking about this. I imagine this is something like an Almodovar film.

JM: It was like that.

PA: But even so, you knew from a very young age you weren’t into what they were telling you.

JM: I wasn’t sure how to say it, but I was suspicious. Things became more clear as I grew up and got the vocabulary. And then two things happened when I moved to New York, when I was thirty. The hair was one thing and the other thing was that on a holiday a Lubavitch said to me, “Are you Jewish?” And I said, “Not today,” and that felt so good.

PA: Why “not today?”

JM: Growing up exclusively in a Jewish environment made me think, what does it mean, not only for others to be afraid of you, but for you to be afraid of others? I grew up very much as a minority; it was a very secluded childhood Judaism didn’t do it for me for a long time… I was terrified of Yom Kippur. The idea that god was going to write your name in the book of life. Like, what if he wouldn’t write my name?

PA: That’s so interesting because I always think of you as so culturally Jewish.

JM: Well that’s only one aspect. Culturally, however, I identify with Judaism—the neurotic side—Woody Allen, Freud, the sense of humor. Culturally, I really embrace Judaism. I love culture and books and history. What I have a problem with is the religion. And the patriarchy. Feminism helped me look more critically at religion. I met a group of women in Colombia and we were doing experimental theater and I started waking up and learned the vocabulary to name things. It was very much a man’s world.

PA: It still is.

JM: I thought it would be different in the U.S. but when I came here I began to understand that it’s not that feminism failed, but the institutions failed.

PA: That is so fucking perfect. May I ask you, on a totally unrelated note, what’s your favorite drink?

JM: Dry white wine.

PA: How do you eat your eggs?

JM: Scrambled.

PA: How do you drink your coffee?

JM: With half and half.

PA: What’s your favorite Jewish Holiday?

JM: The one with the honey. Rosh Hashanah.

PA: Did you have a bat mitzvah?

JM: Yes.

PA: What did you wear?

JM: A lavender dress. But we had bat mitzvahs by the dozen. If you were a guy, you deserve a bar mitzvah, but for the girls, they were like, we don’t think it’s worth it unless there are a dozen. So I wore a lavender dress and they straightened my hair.

PA: They straightened your hair!?

JM: Every fucking Friday! My ears burned so much.

PA: That’s so horrible.

JM: When I was 16, I said, enough! And now I love my Jew ‘fro and in New York it’s been

celebrated. In Colombia, they feel a little sorry for you.

PA: Speaking of hair, what shampoo do you use?

JM: I don’t.

PA: You don’t?!

JM: It’s a non shampoo that’s shampoo. Specifically for curly hair.

PA: Gefilte fish or lox?

JM: Lox.

PA: Favorite pair of shoes?

JM: Margiela boots with peeking toes.

PA: Of course. Five things in your bag right now—oooh, that’s a nice bag! Is that Comme des Garçons?

JM: Thank you. Yes. My keys, sweatpants, checks, matches, but I don’t smoke, gum, lipstick—always lipstick.

PA: Red?

JM: Wine for the day, red for the night.

Periel Aschenbrand, a comedian at heart, is the author of On My Kneesand The Only Bush I Trust Is My Own.