We Called Him Mundek. He Sang in Yiddish on Shabbat. And He Will Be Missed.

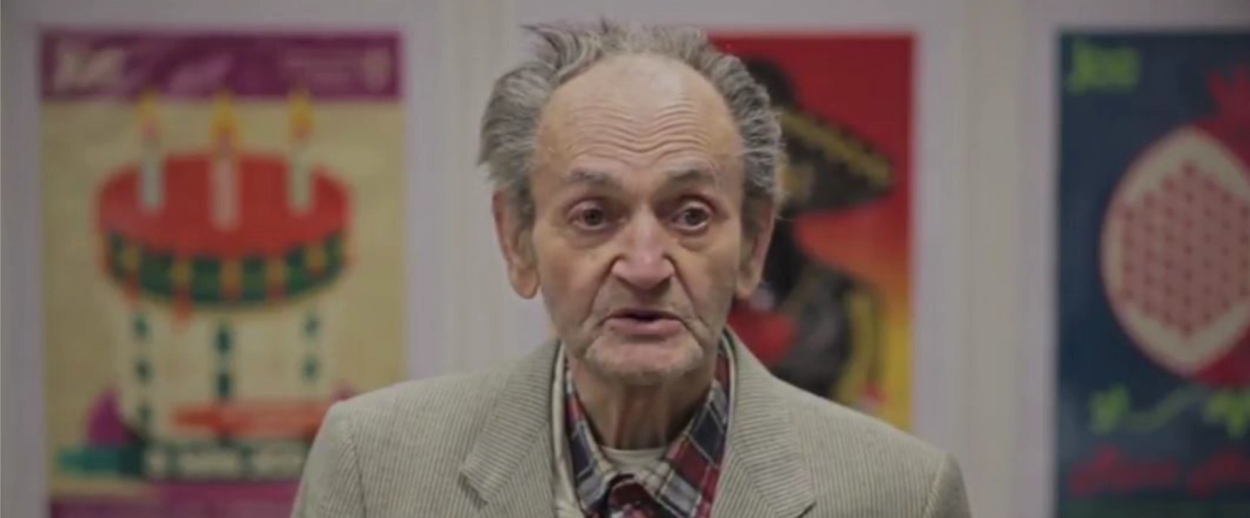

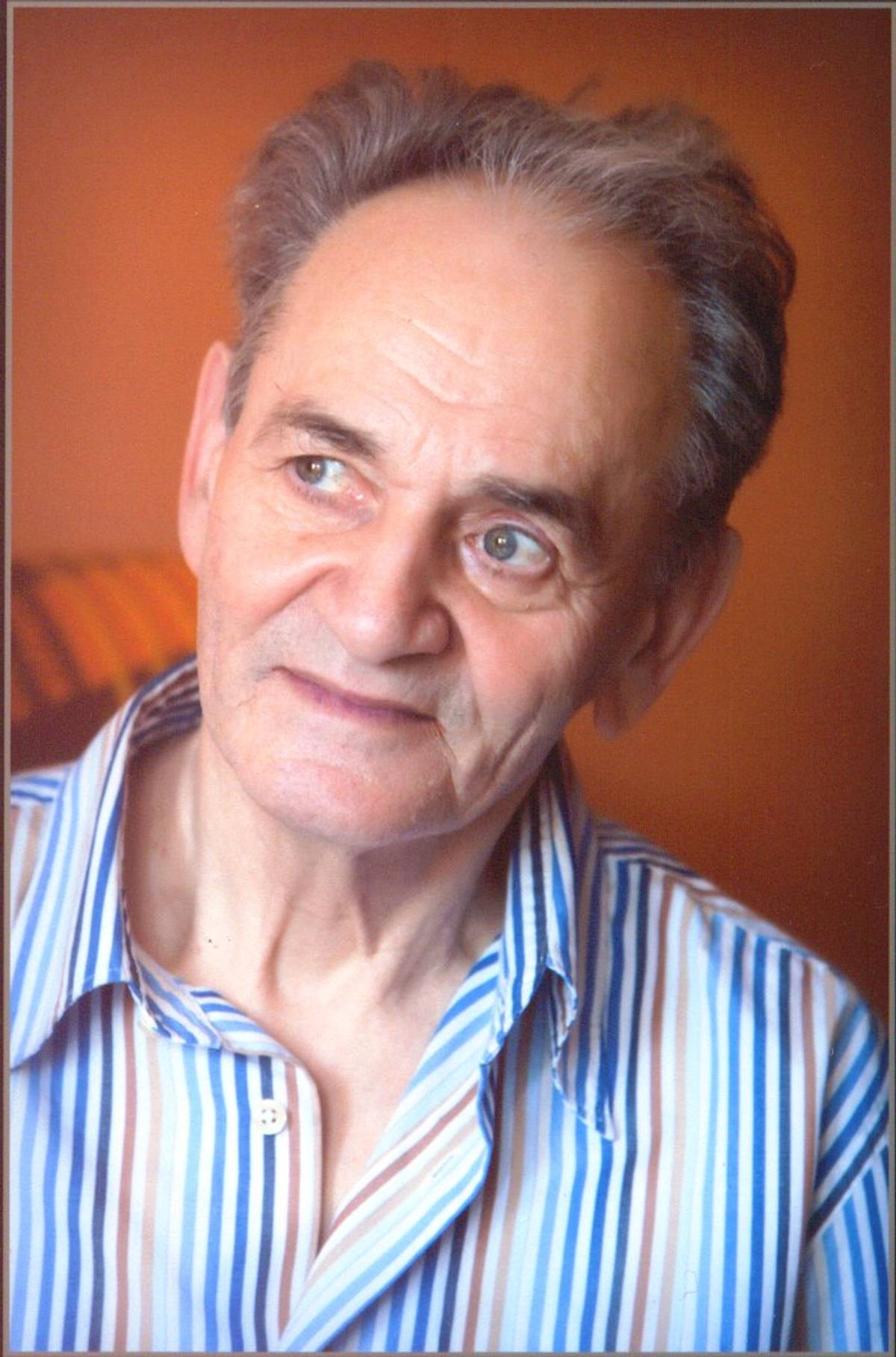

Emanuel Elbinger, a Holocaust survivor and beloved member of Krakow’s Jewish community, dies at 86

His folding chair was propped up.

It was Friday night at Krakow’s JCC as people walked in from services, greeted each other, took their seats. It could have seemed like any other Shabbat dinner, but locals hugged a bit longer, nodded more intensely, and walked by that empty seat with their heads down.

That morning, Emanuel Elbinger—a Holocaust survivor and beloved member of Krakow’s Jewish community known as Mundek—had died. He was a hallmark of these dinners.

Mundek was gentle, unassuming, kind. He spoke excitedly—even weeks before his death—especially when he met other Yiddish speakers, such as young volunteer Marc Schorin who interviewed him in Yiddish in 2016. Anyone who attended a JCC dinner will remember Mundek singing a medley of seven Yiddish tunes, which the community sang together on Friday night before observing a moment of silence.

Born in Krakow in 1931, Mundek lived 15 miles away in Nowe Brzesko before the war. He survived in hiding. His extensive biography was recorded in 2005 by the non-profit Centropa. There are the beautiful details: his grandmother’s house—with a balcony—at Main Square 9; a non-Jewish nanny who took him on walks and taught him Polish; a blonde sweetheart at 16, Marta Fiegner, with whom he reconnected later in life. And the horrors: fear, starvation, loss.

Over the past decades, Mundek found solace in monthly meetings with members of the Children of the Holocaust Association. When he was well, he visited his family in Belgium. Despite his career in electrical engineering, he pursued his artistic talents by collecting Judaica and making sculptures of Jews that he “remembered from before the war.” He gave these as gifts—to an Israeli tour guide who was moved to tears seeing faces that reminded him of his grandparents, to Prince Charles and Duchess Camilla at the opening of Krakow’s JCC in 2008.

While humble, he knew what he was good at: “relations,” “problem solving,” “drawing.” After the war, while living in a Jewish children’s home in Krakow, he was encouraged to study art. “They saw my drawings—I remember I drew Staszic (Stanisław, 1775-1826, a leading Polish scholar and reformer of the Enlightenment period) and other people. I could draw well,” he said.

In early 2012, I sat in Mundek’s one-room apartment in Krakow with my dear friend Joanna Sliwa, who recently wrote about him for the JDC Archives. He walked around excitedly showing us his treasures—the most important objects in the world to him—eventually reaching under his bed. The pizza box was covered in a layer of dust and his eyes lit up as he opened the top to gaze at dozens of handmade embroidered matzo covers.

“I remembered things from my pre-war home. I wanted something that was like before,” he said, recounting—object after object—mesmerizing tales, this one about an embroidery expert who agreed to help him make these during Communism because a Jewish doctor saved her father during the war. “We came up with the patterns together. I brought the letters from Antwerp…aleph bet…aleph bes...”

I feel honored to have spent time with him, documented his contribution to the revival of Yiddish, and kissed him on the cheek three times at Shabbat dinners for many years.

This Tuesday at noon, about 40 people gathered outside at the 11-acre New Jewish Cemetery on Miodowa Street founded in 1800 in Krakow. The crowd faced the open doors of the main building, listening to the faint hums and chants of the service inside. When it ended, dozens of mourners poured out of the room, following Mundek’s casket toward his burial spot near the wall where over 100 people gathered to pay their respects. Words were not needed to acknowledge his impact on this community and what losing him represents.

“He once said that after what he experienced during the war, he didn’t want to bring children into this world,” said JCC Executive Director Jonathan Ornstein, who was with Mundek the night before he died. “Recently, he told me that seeing changes in Poland and Krakow made him wish he had had children here. Still, he touched so many lives.”

Dara Bramson is a journalist covering Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia.