Lessons From a Boy and His Lion

Renato and the Lion is a gorgeous new picture book that teaches us about art, family, and history—and parallels many of our own families’ immigration stories

Renato loved his home in Florence, Italy.

He loved the people there. And the food there.

But he especially loved the art there.

It was everywhere.

So begins Renato and the Lion, a new picture book by debut author/illustrator Barbara DiLorenzo. With ravishing watercolor illustrations, it combines history and magical realism in a way that will entice the youngest readers.

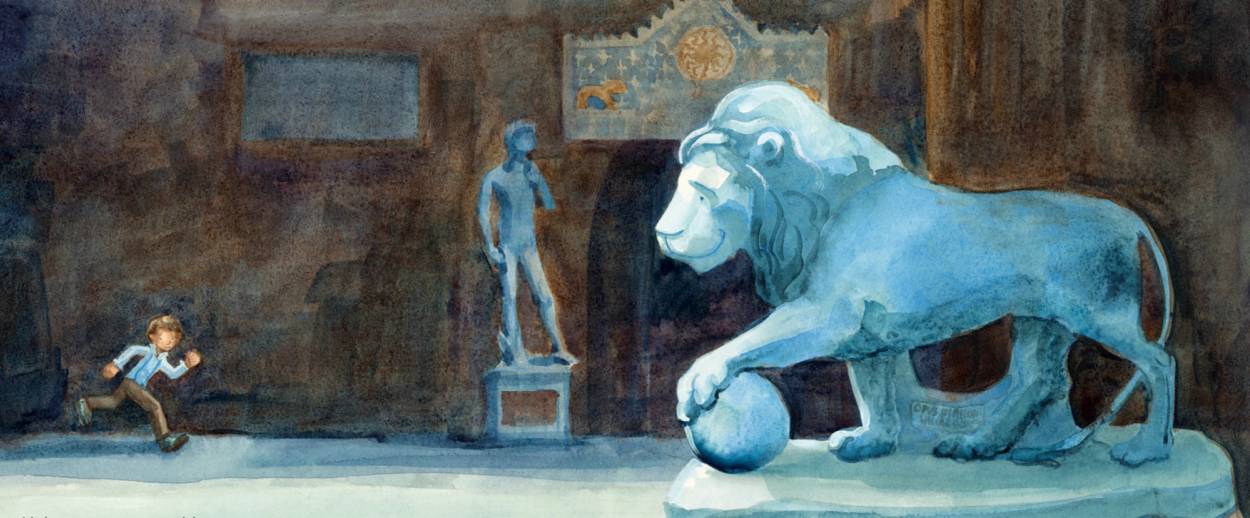

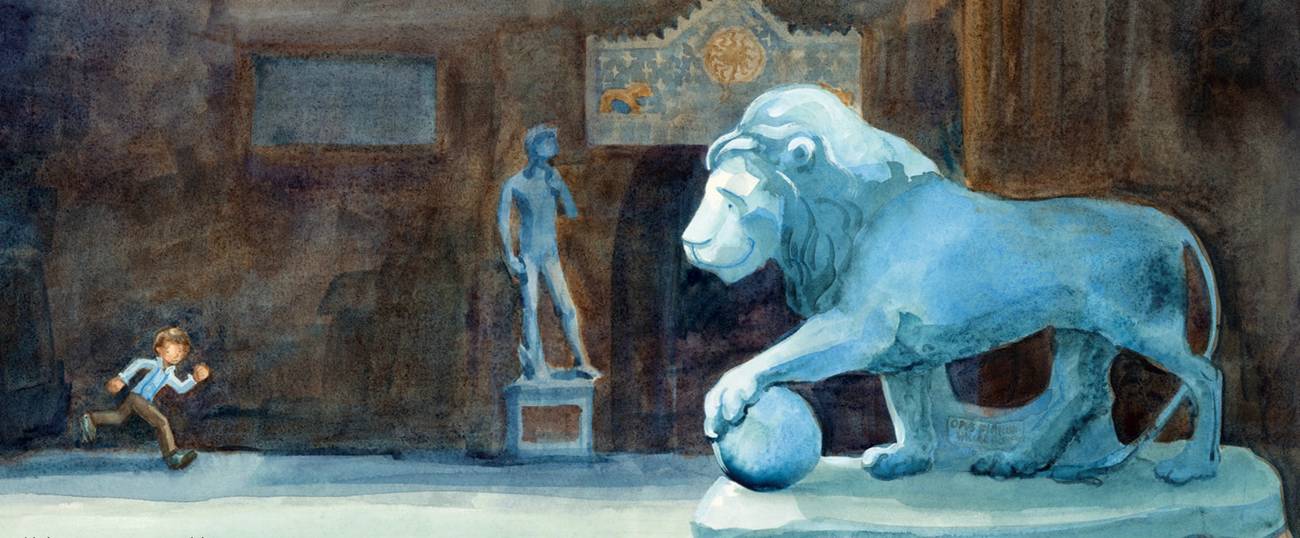

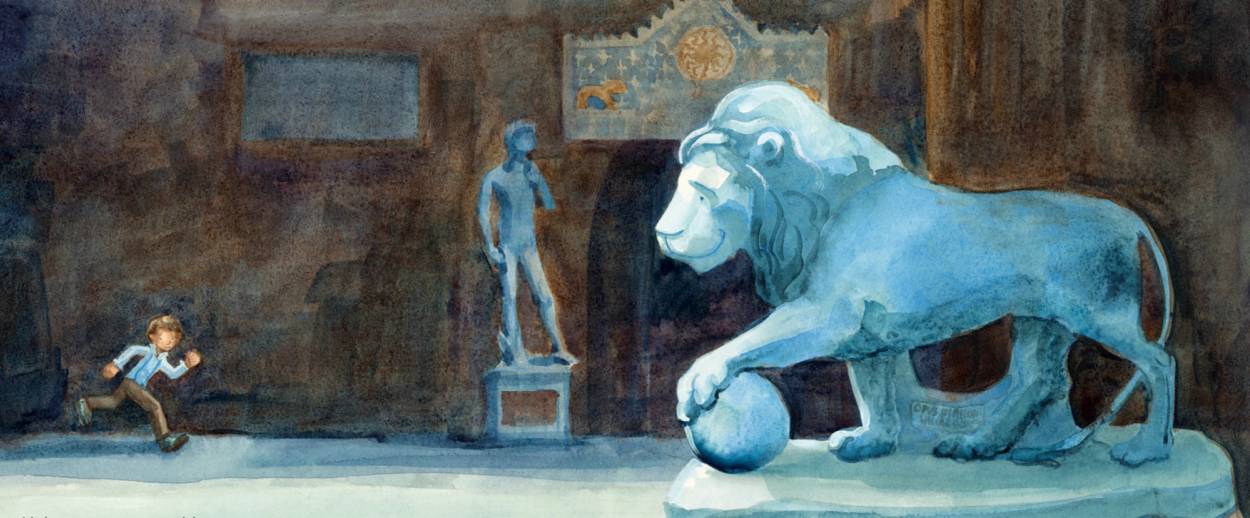

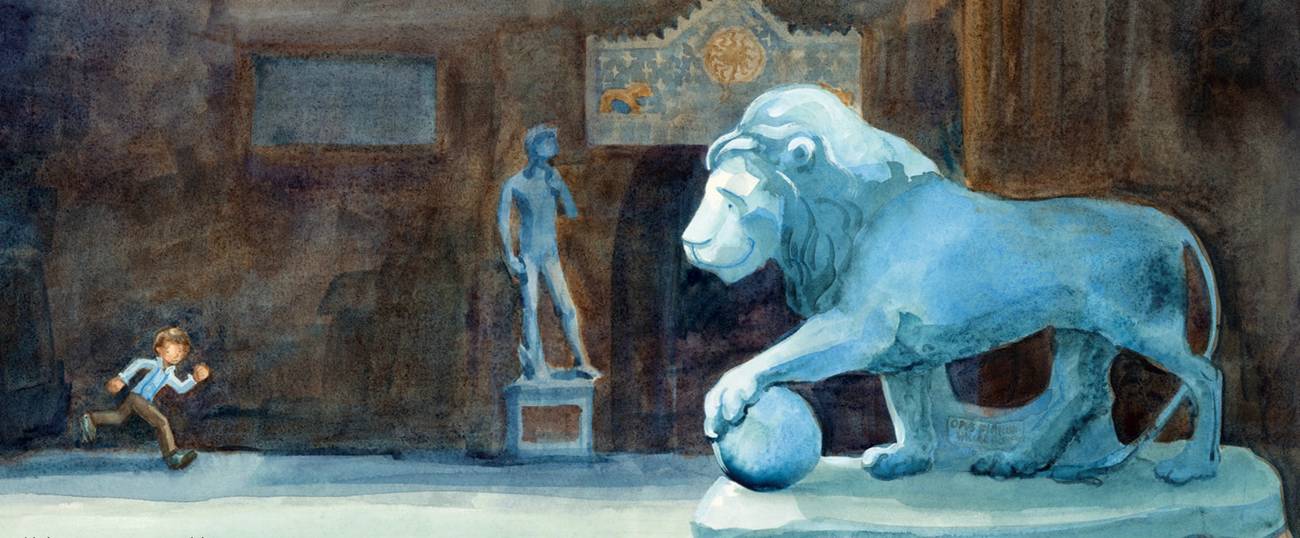

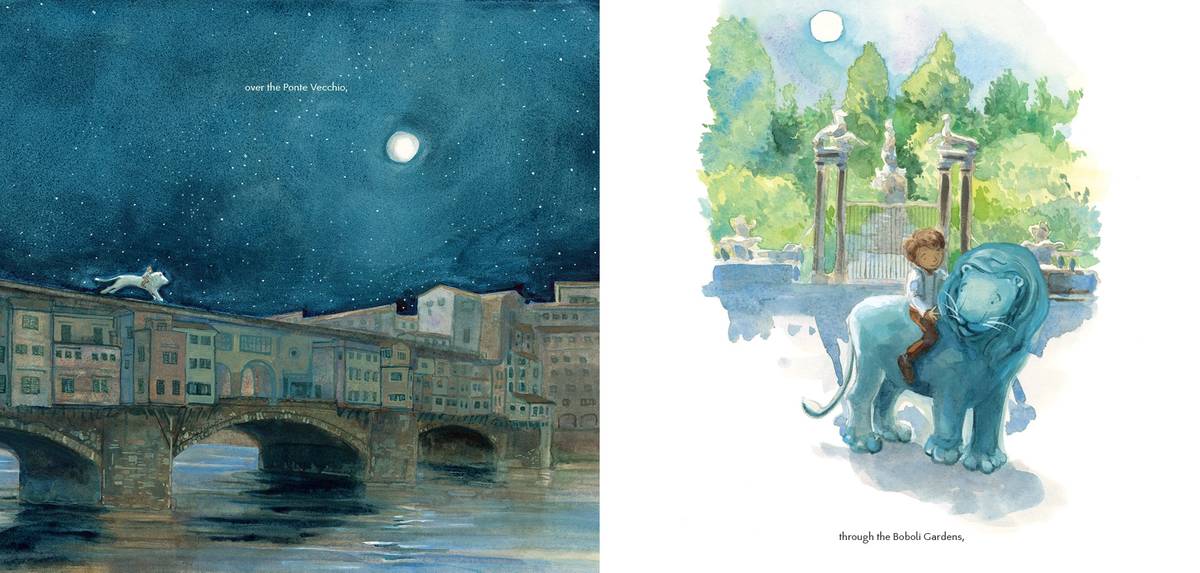

We first see little Renato splashing with his pals in the Fountain of Neptune, gazing up at ceiling frescoes, kicking a ball past the Duomo. DiLorenzo’s wash of oranges, greens and blues bring the beauty of the city to life. Renato’s favorite sculpture is a stone lion, giant paw resting on a ball, gracing the Piazza della Signoria. He says “buongiorno” and “buona sera” to it every day. But one day, Renato’s father, an art restorer, shows him that Michelangelo’s David has been encased in a dome of brick, to hide it from the growing numbers of German soldiers in the city. Renato wants to hide his beloved lion behind a wall of bricks, too, but there’s no time—the family will have to flee to New York the next day. That night, he dozes off on the statue’s back, and the lion comes to life. It takes him on an enchanted tour of the marvelous city he has to leave for his family’s safety. The moody painting of Renato and the lion crossing the silent Ponte Vecchio, with the stars glittering in the sky and the moon reflected in the water, is particularly entrancing.

At the end of the duo’s journey, the lion disappears. But in the morning, Renato learns that his father has indeed built a protective wall around his lion. The family escapes on the ship Henry Gibbins,; which cruises into New York Harbor, past the Statue of Liberty.

Soon, New York City feels like home. We see Renato splashing with new friends in the fountain in front of the Plaza Hotel, an echo of the earlier Florentine illustration. The years pass, and a now-elderly Renato visits the New York Public Library with his granddaughter. “Can I pat the lion?” she asks him. “Of course,” he says. Then he tells her, “I once knew a lion.”

Renato and his granddaughter visit the city of his youth, see the Boboli Gardens and eat giant cones of gelato. And guess who they discover has survived the war, and is still in the Piazza della Signoria?

The story stands on its own as a wondrous story of family, love, and escape … but it’s even better when used as a jumping-off point for a conversation about history and current events. The parallels to many of our own families’ immigration stories—and to the dangers facing today’s refugees—are hard to miss. DiLorenzo, who fell in love with Florence as a student at the Rhode Island School of Design, provides a bit of help for parents and teachers in her acknowledgments and back matter: She interviewed restaurateur Doris Schechter about her childhood voyage on the real-life Henry Gibbins, and depicts Schechter as a little curly-haired girl on the ship. Photojournalist Ruth Gruber, who escorted the refugees to safety in 1944, is shown on deck too, as a smiling woman with a camera. You can tell your kids, as DiLorenzo does in the afterword, that the Henry Gibbins was the one and only transport President Roosevelt allowed to bring refugees from Europe to America during World War II.

You can also say that of the 982 refugees on board the Henry Gibbins, 874 were Jews. Gruber, who was fluent in Yiddish, organized English lessons on board, became known as “Mother Ruth,” and taught refugees to sing “You Are My Sunshine.” (Three years later, she chronicled the journey of the Exodus, inspiring Leon Uris’s book of the same name; she talked about her experiences on a Tablet podcast in 2007. She died last year, at 105.)

What can kids learn from Renato’s escape, from America’s decision not to allow in more refugees during the Holocaust, and from debates about immigration today? We might also talk to children about how storytellers often take liberties with facts. DiLorenzo acknowledges in her explanatory text that she never found out whether Renato’s lion really was bricked up during the war, though she tried—she did a ton of research. (Also, there are two lions in the piazza! But that doesn’t make as intimate a story as one boy and one lion.) And she doesn’t note in the main text that the refugees of the Henry Gibbins were sent to a refugee camp upstate, not to New York City. I’d argue that because she tells us what really happened in an afterword, and doesn’t hide the truth, she’s free and clear. And she gives us parents and teachers the opportunity to discuss the art and science of lively non-fiction writing. What makes stories beautiful and exciting? Because without a doubt, Renato and the Lion is both. Don’t miss it.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.