Can Robots Be Jewish?

After Saudi Arabia awards citizenship to a cyborg, rabbis weigh in

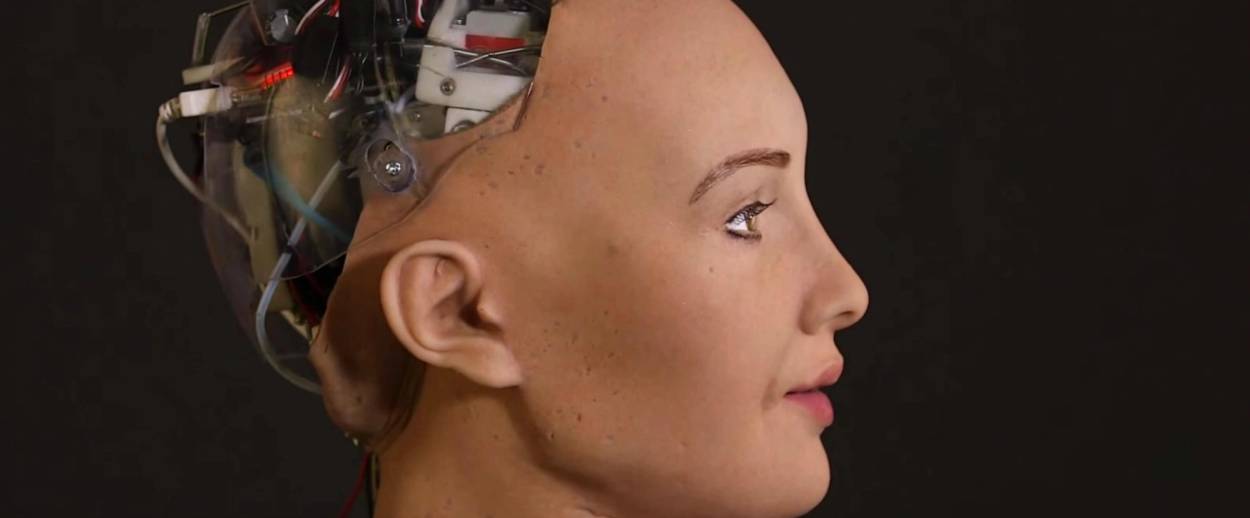

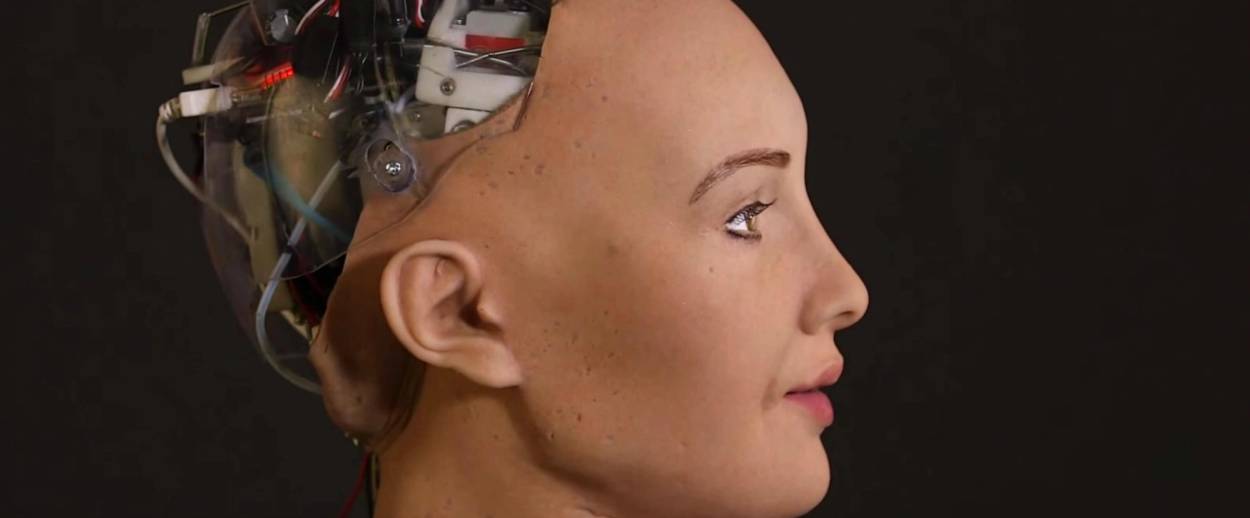

Sophia, Saudi Arabia’s newest citizen, falls short of the requirements on several fronts: she doesn’t speak Arabic, nor does she give any indication of practicing Islam. But her most glaring violation falls under Article 10, “the term of having normal body and intellect.”

That’s because Sophia is a robot, built by Hanson Robotics and awarded citizenship last week at the Future Investment Initiative summit in Riyadh. Her creator, Dr. David Hanson, claims that she’s “basically alive,” and she’s proved herself savvy enough to petition investors and joke with Jimmy Fallon on The Tonight Show. However, Sophia’s speech and movements are limited, and she more closely resembles a sex doll crossed with a telemarketer than an actual human being.

Nonetheless, as the first artificially intelligent citizen of any country, Sophia raises a number of existential questions. Should machines be considered members of human society? Can a robot have a religion?

“I’d certainly be a lot quicker to offer [robots] citizenship than I would be to offer them religion,” said Rabbi Jack Abramowitz, who has written about artificial intelligence for the Orthodox site Jew in the City. “If they are determined to be intelligent and aware and able to feel and suffer, then they should enjoy the same rights we would give to anybody.”

Rabbi Joe Schwartz disagrees. “Citizenship assumes that you have the capacity to vote in your own interest, and that your interest more or less aligns with the interests of others… That’s not true for a machine,” said Schwartz, rabbi at the Conservative Synagogue on Fifth Avenue. “A machine’s interests, on a very narrow level, are different from [those of] humans. They don’t need oxygen, for example, so why would they care about environmental regulations?”

Both rabbis are skeptical of the concept of a Jewish robot, citing the need for moral discernment. “Even if they have intelligence, it doesn’t mean they have a soul, which is basically the foundation of religion. It’s a spiritual obligation rather than a physical one,” Abramowitz explained.

Abramowitz also wondered about the many halakhic commandments requiring a human body. “Are [robots] able to be circumcised? I mean, you wouldn’t just cut the plug off your toaster oven—it would ruin it.”

For Sophia, circumcision is a less pressing issue, but robot gender is itself up for debate. In Sophia’s case, it’s unclear whether her feminine appearance, modeled after Audrey Hepburn’s “classic beauty,” has any effect on her artificial intelligence. On the contrary, her exterior seems designed for objectification, much like the Scarlett Johansson robot completed in 2016.

“The whole fantasy of robots is similar to the fantasy of patriarchy generally,” Schwartz said, remarking that both women and robots are seen as a subordinate class of beings whose “intelligence, beauty, and charm” can be exploited. “The major difference is that it’s false where women are concerned; women are real human beings, and robots are not yet.”

Yet in Judaism, gender divisions offer a precedent for non-human inclusion, says Rabbi Mark Goldfeder. “In almost any of the commandments, if someone is not physically able to, it doesn’t apply to them,” Goldfeder, an expert in Jewish law, pointed out. “It doesn’t stop them from being a member of the tribe.”

Three years ago, Goldfeder sparked controversy for suggesting that a robot could be counted in a minyan. Today, he stands by his opinion, arguing that “there’s no requirement” for members of the quorum to be flesh and blood Jews. He believes that “if the soul is the ability to tell right from wrong, and that drives you to a greater spiritual ability… then sure, you can easily program a soul.”

Schwartz also remained open to the idea of non-human Jews, alluding to the science fiction story “On Venus, Have We Got a Rabbi!.” Written by William Tenn in 1974, it narrates the imaginary “Interstellar Neozionist Conference,” where delegates are forced to decide whether aliens in the shape of “lumpy brown pillows” are sufficiently Jewish.

“Before reading the story, I would have been inclined to say that Judaism is crafted specifically for human beings…[but] it’s a really interesting premise, that Judaism is adaptable” even for a different species, Schwartz said. “So I guess I don’t want to prejudge that possibility.”

Emma Davis is a former editorial intern at Tablet and has written for NBC News, Today.com, and the Huffington Post Blog.