A Conversation with Mary Peldman, the New Principal of The Sephardic Academy

“Studying some of the classic Sephardic books has opened us up to a range of different approaches and pedagogic models”

Here’s a history lesson for today: In 1901, a Sephardic woman named Alice Franchetti founded the Montesca School in Italy, experimenting with innovative pedagogical methodologies and providing free education for the children of farm workers. In 1905 she partnered with Maria Montessori on developing a pedagogic methodology originally labeled the “Method Franchetti-Montessori”—until fascists in Mussolini’s government demanded the omission of Franchetti’s name. It is now universally known as the Montessori Method.

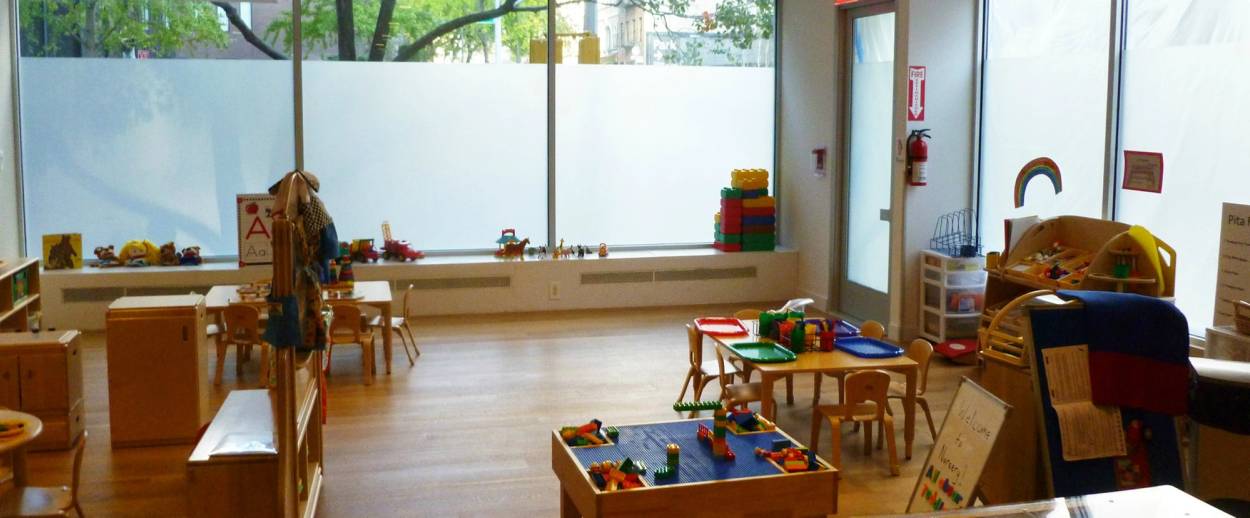

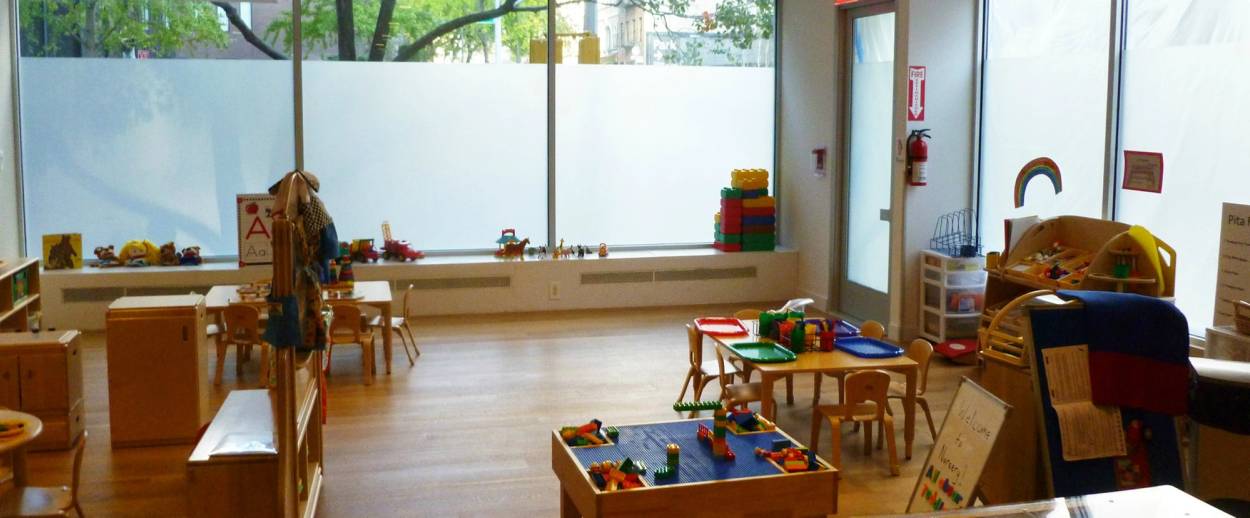

That method is one of the inspirations for the teaching philosophy of The Sephardic Academy, a new elementary school in Manhattan. This month, the school appointed a new principal: Mary Peldman, who spent the last ten years working at the Beit Rabban Day School on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. I spoke with her this week about her background, her own teaching philosophy, and how we should view Sephardic tradition as more than just a geographic designation or lineage, but as a universalist approach.

Miriam Levy-Haim: Tell me more about why you’ve decided to make this move now.

Mary Peldman: It’s an opportunity to create something new and hopefully amazing. And it’s an opportunity to serve the community that I came from, which also feels like a very special opportunity. My parents are actually Egyptian and I grew up in the Sephardic Community in Brooklyn.

Miriam: Is the school catering to the Syrian-Egyptian community?

Mary Peldman: It is a Sephardic school. The part that is really compelling is that we’ve done research into the way that people learned during the Golden Age of Spain, when Jews were able to partake in society and also maintain their strong Jewish identities. So that concept of being integrated into society but maintaining a heritage of pride and practice is sort of the concept that the school is based on. In addition to that there is Sephardic learning around tefillot and traditions, but there is certainly Jewish diversity within the classroom, and we are seeking to have that Jewish diversity in the classroom as well.

Miriam: That’s actually one of the things I also thought was compelling about the school—that you define Sephardic as more than just a geographic designation or lineage, but as a universalist approach. But can you explain this in more detail: What does a universalist approach to education look like in an elementary school classroom?

Mary Peldman: It’s a day where subjects are integrated with each other, which is not so unusual for early childhood or kindergarten, but frequently what happens in schools is that once children get to first grade the day becomes bifurcated and they are learning Judaic Studies in one part of the day in Hebrew, and another part of the day they’re learning General Studies. We don’t want it to feel like a separate experience, the Jewish-Self and the General-Self, or American-Self. The subjects will sort of vary throughout the day, so that it’s not all one and then all the other. And in addition to that, a real intentionality around project- and product-based learning that requires knowledge of both. So it could be a scene design project on a topic that’s related to what the children are studying in Chumash, or it could be an artwork that integrates various different parts of several disciplines. Having the staff to support that kind of model throughout the day will allow the learning of each subject to strengthen the other, so that if children are learning character analysis in literacy they can also use those same skills to analyze Parshat Ha-Shavua and other texts.

Miriam: You said you did research in medieval Andalusian Jewish education. Could you tell me a little about that and whether it impacted your curriculum development?

Mary Peldman: Studying some of the classic Sephardic books has opened us up to a range of different approaches and pedagogic models. Our pedagogies are probably going to be most closely connected to sort of progressive education, but that sort of universalist outlook and universalist approach comes directly from the way that it was done in Spain.

Miriam: How many years has the school been around for? How many children are there now?

Mary Peldman: This is the first year that there’s a kindergarten, but the school has developed a preschool over the last seven years. Between the preschool, which serves toddlers, so two year olds, and the kindergarten, currently it’s close to 100 students.

Miriam: You’re now recruiting for first grade?

Mary Peldman: Yes, and kindergarten. Our current kindergarten will be our first grade next year, and each year develop another grade.

Miriam: What’s your long-term vision for this school? What are you hoping for it?

Mary Peldman: I’m hoping two things. One is to truly be able to serve all of the children who want this type of education, whose parents are seeking an integrated Judaic and general education, and to be able to provide for them an individualized education that truly helps every student reach his or her own potential. So in that way children who have a range of different intelligences are recognized for those intelligences—whether it’s academic or spiritual, whatever their strengths are, to help them develop them and strengthen them, and then to support them in any areas that they need support and make sure that they’re developing socially, emotionally, spiritually, cognitively, intellectually, and are truly growing optimally. The second big piece of this is, in looking at the education system overall in America and in other countries, we really want to create something that’s more in line with what we believe children are capable of. Young children have tremendous brain elasticity and tremendous capacity, and we want to tap in fully to all of the things that they are ready to learn and do and help them to cultivate those skills and content knowledge and ideas and understanding in a way that is very sophisticated. That, we believe, is something new that the school will be bringing to the already pretty robust Jewish education landscape of New York, but truly something that we could add to that.

Miriam: Do you have specific ideas in how you want to do that, or are these general overarching principles?

Mary Peldman: All of our skills-based areas are going to be using researched-based curriculum, methodology. A proficiency model for second language learning coupled with immersive Hebrew, math curricula that aim towards mastering and applied knowledge, literacy curricula that use a balanced approach to literacy. By which I mean, they’re not “studying for tests”; they’re displaying their knowledge through projects, through presentations, and assignments. And all of those projects and assignments are being designed currently in ways that are very thoughtful for helping children develop all of their 21st century skills, like critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, compromise. Through the design of these sorts of projects, which are long-term assignments that also help develop executive functioning, they’ll be really flexing those intellectual muscles and those skill sets that we know are critical to success.

Miriam Levy-Haim is a student at the CUNY Graduate Center’s Master’s program in Middle Eastern Studies, with a particular interest in the history of Jews of the Middle East. She has worked for several Jewish educational institutions developing curricula for adults and teens.