On Geekery and Misogyny

On the 40th anniversary of the first computer bulletin board system, it’s amazing how little has changed about the web’s tech bro culture

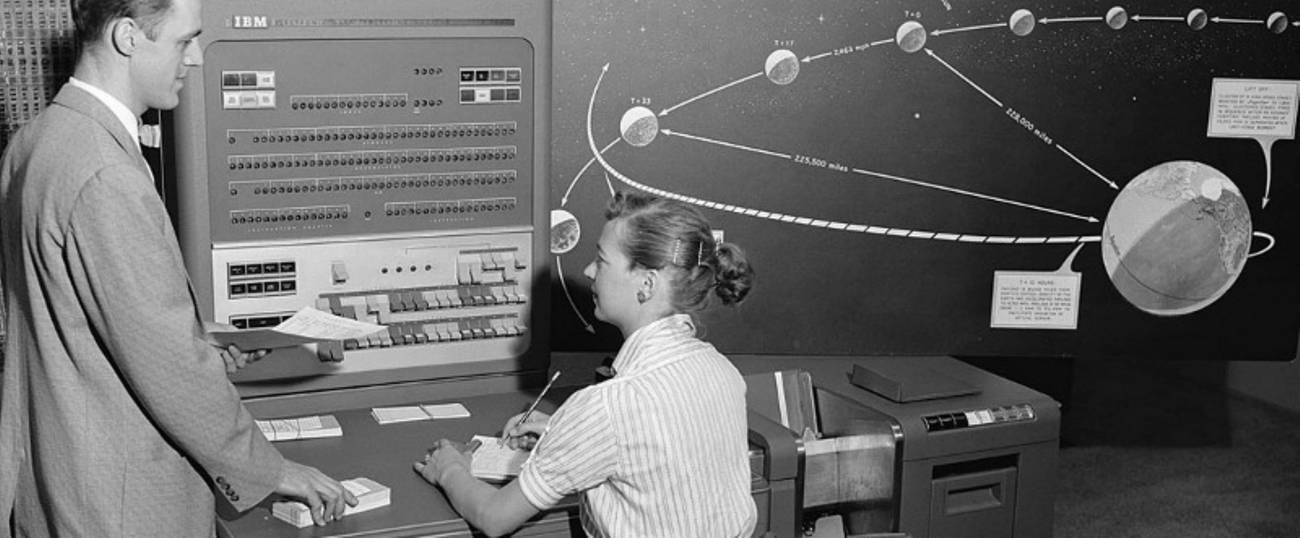

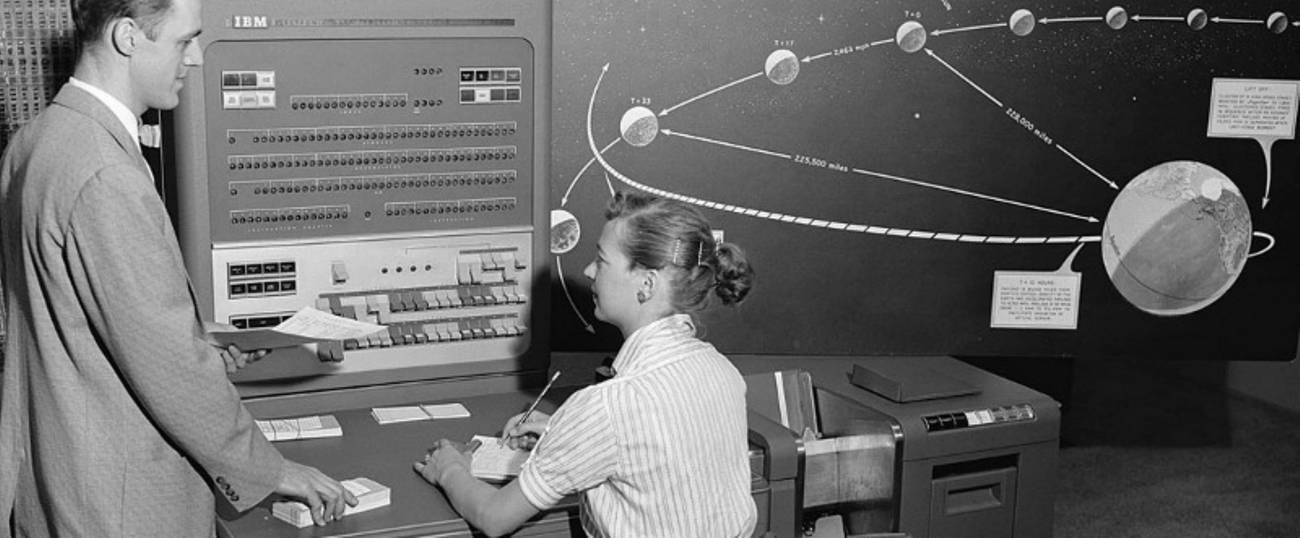

Today, February 16, 2018, is the 40th anniversary of the launch of the first computer bulletin board system: Ward & Randy’s CBBS. The launch story: Ward Christiansen and Randy Seuss, Chicago-area nerds, were trapped by the Great Blizzard of 1978 and given the gift of time to work on their pet project: A computerized message center. The goal was to allow members of their club, the Chicago Area Computer Hobbyists’ Exchange (CACHE), to call each other’s modems and alert each other about forthcoming meetings and interesting newsletter articles. (At the time, the club used an actual bulletin board, with thumbtacks.) In an online history, Ward recalled, “Began writing the real bulletin board program (Called CE.C by Randy—egotistically, the ‘Computer Elite’s project C—Communications’). Randy put together the hardware. Very early in Feb, started testing. No one believed it could be written in 2 weeks of spare time so we called it ‘one month’ and to this day declare Feb 16 as the birthday.” (Randy, incidentally, went on to create the world’s first public-access Unix system, and CBBS evolved into Chinet, which still exists today.)

Upon reading about this momentous anniversary, I realized that I too have a BBS anniversary. Twenty-five years ago, I reported a story for Sassy Magazine—a snarky, funny, politically progressive publication for teenagers—called “Hi Girlz, See You in Cyberspace!” about the mysterious hidden world of BBSes. Since Sassy was constantly being accused of popularizing cool underground things for popular consumption, I noted in my story, “Whee, another culture to co-opt!”

At the time, Sassy had a lovely boy intern named Ethan (googling, I discovered that he is now the Los Angeles Bureau Chief of the Wall Street Journal, so you go, Ethan) who helped me buy a used modem from some dude in the financial district and then hook it up. I created an account on MindVox, a months-old BBS that already had a cool-geek reputation. I described it as “a great big opinionated jabbering technotronic community.” Which would now be Twitter. Ethan helped me translate nerd to English as I explained to our teenage readers that “with a computer and a modem (a wee device that hooks computers to phones) you can talk to people all over the world about art, music, sex, boogers, politics, technology, why you hate 90210, the meaning of life.” (Which, hm, would also be Twitter.)

The World Wide Web had been invented in 1989, but wasn’t widely available until 1994, when its creator Tim Berners-Lee moved from Switzerland to Cambridge to found the World Wide Web Consortium, devoted to making the web’s source code available to everyone. In 1993, MindVox used an intimidating all-text interface, and I was slow to pick it up. I’d talked to a few young women on IRC (Internet Relay Chat, which I called “Internet Relay Channel” in Sassy, causing men all over the world to call me a fucking moron) but couldn’t figure out how to find them on the bulletin board. So I sent a message to the entire community outing myself as a journalist and saying I was looking for women to talk to about being a minority in this community.

Mistake. Dudes went on the attack, saying I was obviously looking to frame hackers, phreakers, and porn purveyors and, worse, that my presence would (as I wrote then), “open their secret society to hoards of dumb-bunny giggling teenyboppers getting mascara stains on their external drives.” It was vicious.

But I wound up talking to a 19-year-old Jewish girl who went by the name reive, who made it clear that gendered attacks were common. “We’re women in a society that has given us claim to certain territories and tried very har dto remove us from others,” she wrote. “If you’re a girl on the net [network] [In 1993, I had to define “net”!] you get sexual advances, you get told you’re not as good as the guys. This world is seen as a private mens’s club.… The thing is, despite all the crap, some of us still want to turn on the computer. Some of us still want to explore. Some of us still believe that technology can help break down our barriers rather than find new ways to put them up.” She also told me, “There’s always that person who pages you 40 times in a row. Which happened to me. I wrote a note to the sysop [Systems Operator] who e-mailed me back saying it was my own personal problem. I was totally aggravated. I ended up sending mail to this person saying ‘Look, I consider this harassment,’ and got this letter back from him saying, ‘You’re a bitch.’”

And of course, women were perceived as being infinitely less knowledgable than men about technology. “There’s often the assumption—oh, you’re a girl, you’re not dedicated to the movement,” reive said. (See today’s “fake geek girls.”) It’s great that the climate has changed so much in 25 years. Ironic winky emoticon! (The word “emoji” did not exist in 1993. We made our emojis by hand, with punctuation marks, and we liked it. Get off my lawn.)

At about the same time my Sassy piece was published, the first issue of Wired Magazine came out. I was the only person at Sassy with a modem, so I began exchanging email with some Wired staffers in San Francisco. Wired had a listicle feature every month called “Tired/Wired”—Wired’s second issue called Seventeen tired and Sassy wired. Then Sassy put Wired on a list of things that were sassy. Our magazines were flirting.

In early 1994, I got an email from a guy named Jonathan, whose title at Wired was “Online Tsar.” It was his job to explain the Internet to people, and he asked if he could come to Sassy to show us this new thing called the “World Wide Web” and talk about ways in which Sassy could have a presence on it. It sounded nuts (he suggested we offer quizzes! On the Internet!) but I said sure, come by when you’re in New York. He did. He had shoulder-length black corkscrew curls and long dangly earrings and a purple leather jacket and he looked like a raver and he could not make our ancient slow modem connect to this “World Wide Web.” I was baffled, yet enticed. He promised to return another time. He left. My colleague Diane ran around the office chanting, “MARGIE MET HER HUSBAND! MARGIE MET HER HUSBAND!”

Reader, Diane was correct. Jonathan and I were friends for a year, then began a long-distance relationship. But all was not well in Sassyland: the publisher stopped paying vendors, and the writing was on the wall. At last, Sassy ignominiously folded. When it was sold to the publisher of the odious, unfeminist Teen Magazine and relaunched in heinous zombie form in 1995, I was still the only person on staff with an email address. So I got all the emails from the early-technology-adopting, furious, broken-hearted teenagers who felt betrayed by this Sassy manqué. I felt betrayed too.

But life goes on. I wrote a book. In December 1995, I moved to San Francisco. Jonathan and I got married in May 1998 under a chuppah in a redwood grove in a rundown old hotspring resort in St. Helena. That makes this year the 40th anniversary of the first BBS, the 25th anniversary of my first BBS, and the 20th anniversary of my marriage to the guy I met through MindVox.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.