New Exhibit Showcases Treasures of Islamic Medieval Art and Science

Brought to New York by the National Library of Israel, the show celebrates both romance and reason

A large number of Islamic manuscripts were brought to New York from the National Library of Israel to star in an exhibition titled Romance and Reason: Islamic transformations of the classical past. Featuring more than 70 manuscripts—24 of which came from the Library of Israel—the exhibit, located at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, opened this week and is set to run through May.

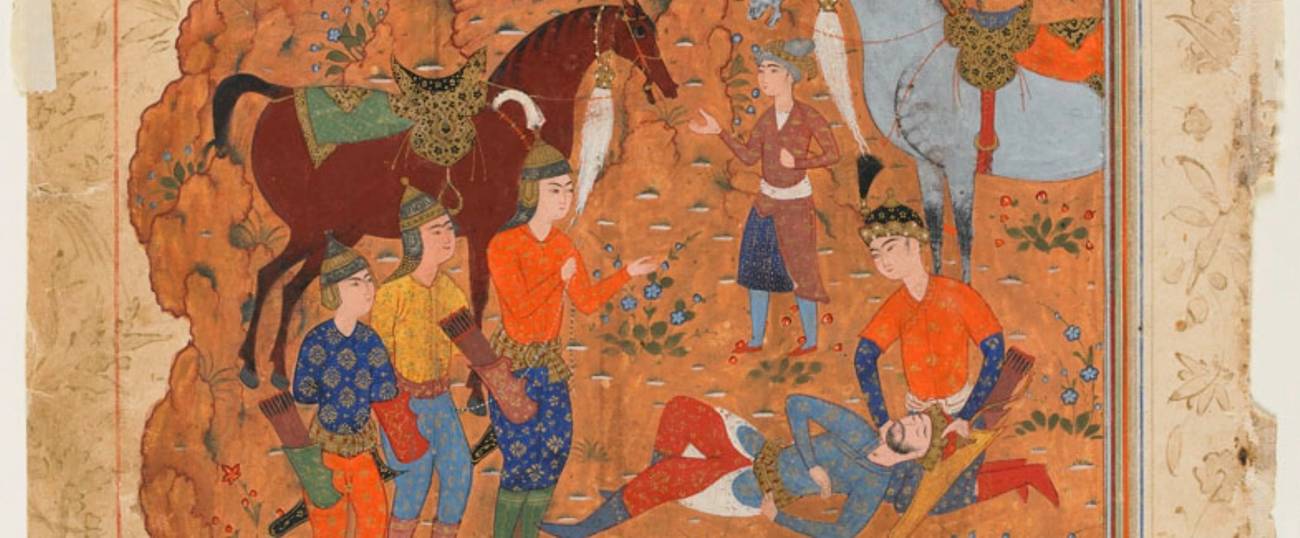

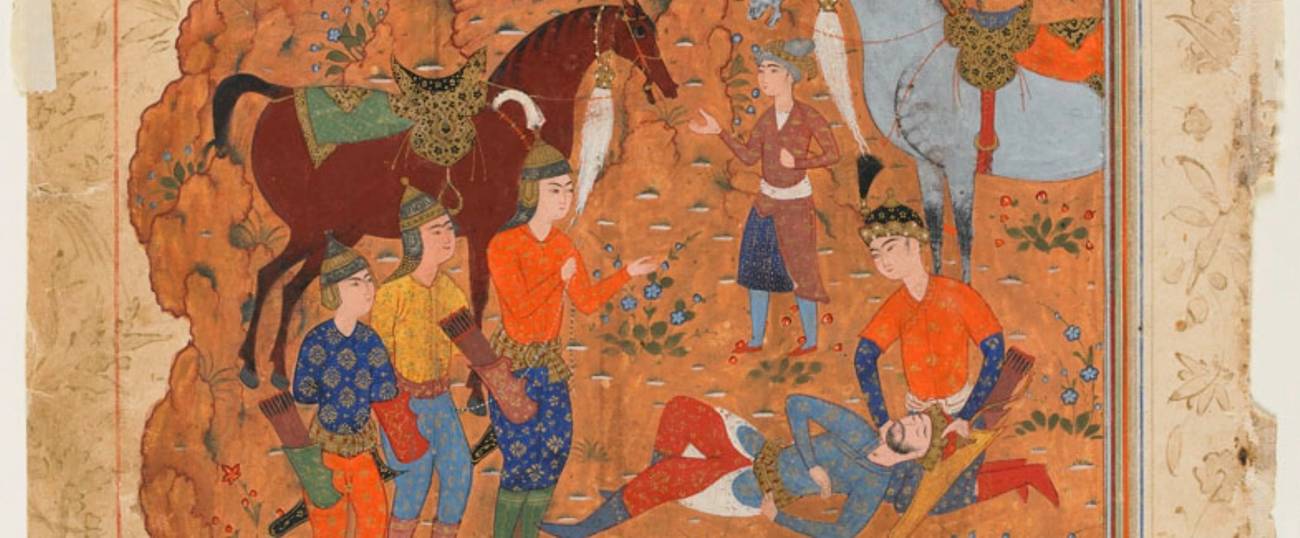

The works are divided into two rooms: The first, “Romance,” shows poetic retellings of the stories on Alexander the Great; the other one, “Reason,” focuses on a series of Islamic thinkers’ writings on science and medicine. Both rooms convey the idea that medieval Islamic intellectuals were deeply inspired by the classical world. What they did, however, was not a mere translation of the classics into Arabic, Persian, and Turkish, but rather a complex, at times critical, elaboration of the ancient texts into a new tradition of poetry and scientific research.

“Translation into Arabic was a conscious process that began in the 8th century C.E.,” said Raquel Ukeles, the curator of the exhibition, who flew from Jerusalem to New York for the opening. “It served as a basis for elaboration.” The translations, she explained, were transformed to fit the society into which they’re brought.

The adaptation does not just occur in the written texts, but in the visuals, too: In one of the colorful illustrations on display, Plato and Aristotle are depicted wearing turbans on their heads as they receive a visit from Iskandar (the Muslim name for Alexander the Great). “I don’t know if this was a conscious claiming,” explained Ukeles. It may have been the result of the same tendency that led Christian European painters to depict Jesus as a Western-looking man, she added.

The section devoted to medieval Islamic reason features manuscripts on medicine, mathematics, astronomy, and even astrology. “Almost all of medieval Islamic medicine is based on the Greek medical tradition of Hippocrates and Galen,” said Samuel Thrope, from the National Library of Israel. Muslim scholars also elaborated on the discoveries of their predecessors, and introduced breakthroughs of their own. Kamal al-Din al-Farisi, who lived in the late 13th century, was one of them: In his Revision of the Book of Optics, he corrected some of the discoveries of his predecessor Ibn al-Haytham, solving an ancient debate on sight.

Back in Israel, Ukeles said, these manuscripts and others are being studied not only be scholars from all over the world but also by children wishing to better understand the history of human thought. “We have a class of Palestinian ninth graders in East Jerusalem who are now working on a research project on these Islamic manuscripts,” she said, proving yet again that romance and reason alike transcend all boundaries.

Simone Somekh is a New York-based author and journalist. He’s lived and worked in Italy, Israel, and the United States.