Who Were You Really, Vashti?

Evil tyrant, proto-feminist, or blank slate onto whom we project our fears and desires

Didn’t have time to read the Megillah this Purim? No worries! To celebrate the holiday, we asked five writers to reflect on the story’s five leading characters. Missed the previous installments? Click here to read about Ahasuerus.

In the Jewish Day School I attended as a child, Vashti was a bad lady, an authority-flouting sexpot who loved to dance naked at parties. She might have also had a tail.

As a purple-mascara-wearing teenage authority-flouter, I learned that Vashti was in fact a proto-Steinem, an attractive woman reclaiming her body and refusing to bend to a man’s dehumanizing performative demands.

So which is it?

The actual text of the Book of Esther doesn’t offer much help. Vashti shows up only for a couple of verses in Chapter 1, and psychologically speaking, she’s a cipher. I’ll paraphrase the entirety of her role (read it line-by-line in both English and Hebrew here, if you wish) so you can see for yourself:

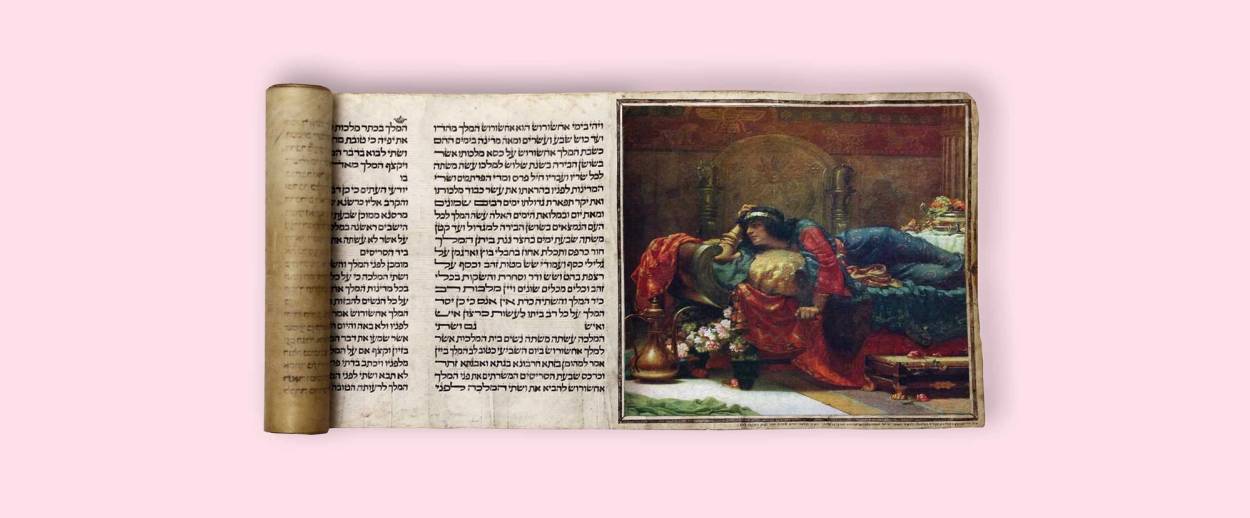

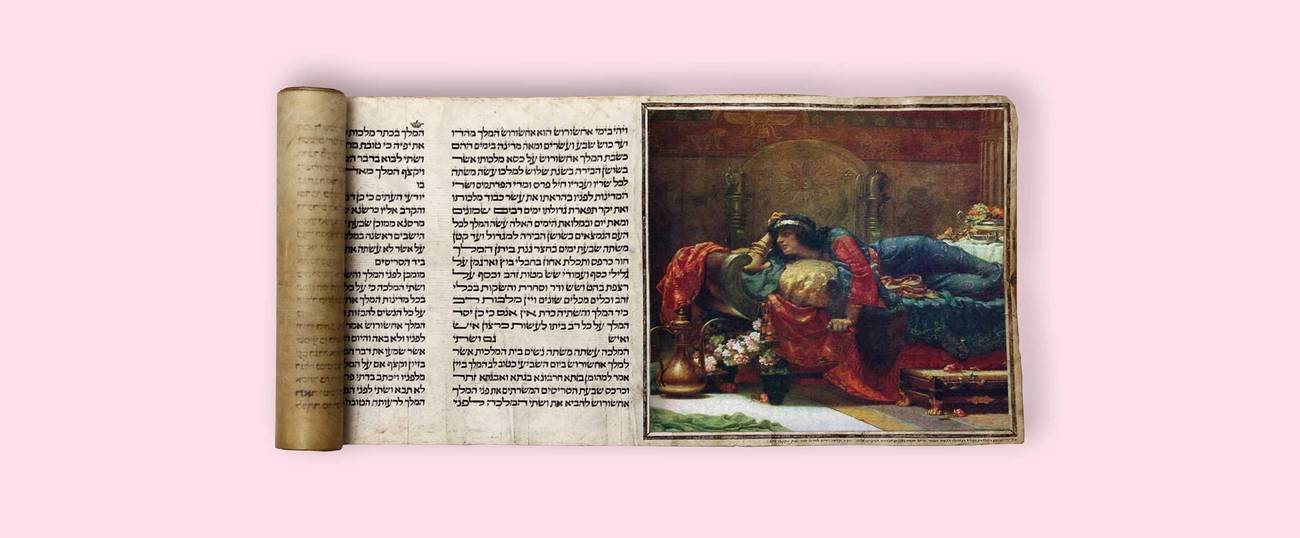

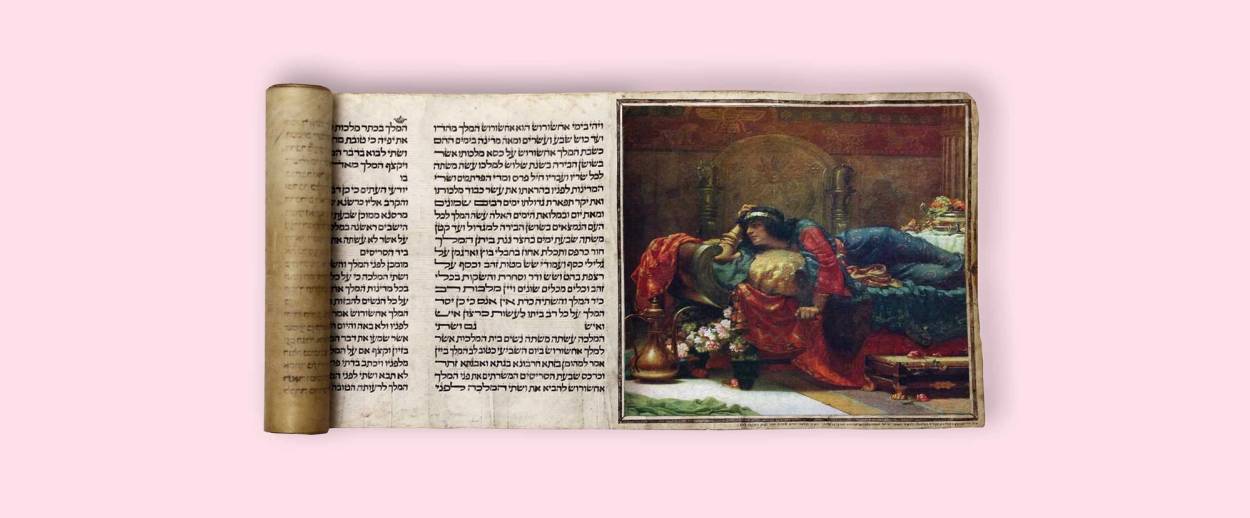

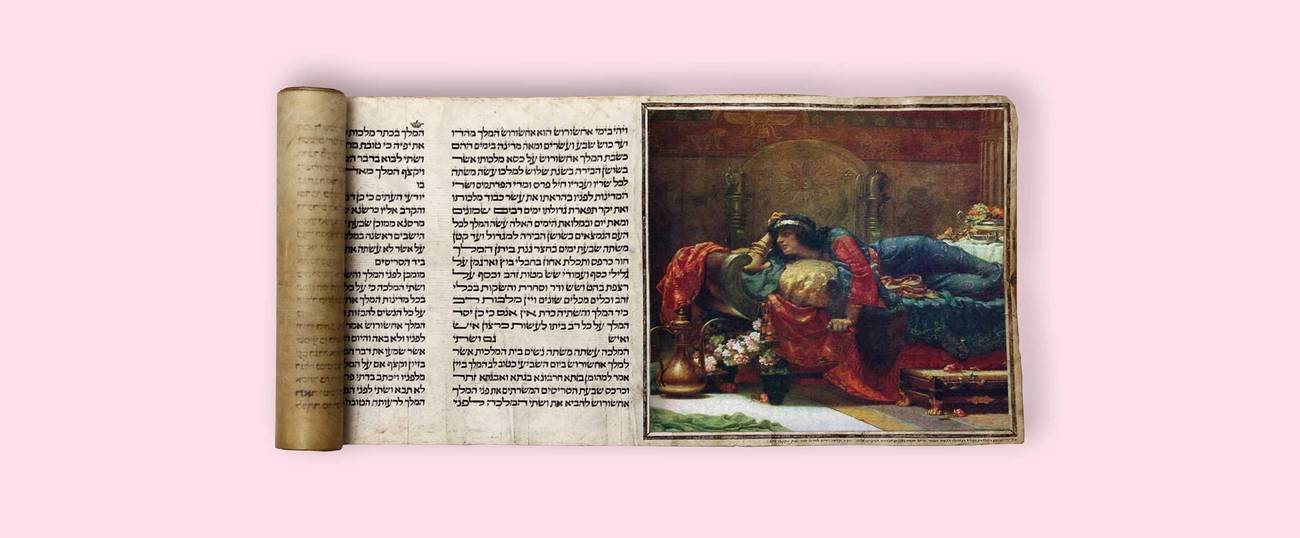

King Ahasuerus threw a fabulous party in his garden court. There were marble pillars and gorgeous wall hangings on silver rods with fine linen and purple wool cords, and there were gold and silver couches, and the floor was inlaid with shells and onyx marble. There were drinks in golden goblets, and every goblet had a different design. Royal wine flowed in abundance. Meanwhile, Queen Vashti was having a feast for the women in the palace. The king asked his seven chamberlains to bring Queen Vashti before him, wearing the royal crown, to show her beauty to the people and ministers, for she was indeed a fox. But Queen Vashti refused to appear. The king grew furious; his anger burned within him. He conferred with his wise men, as was his wont, asking them, “By law, what should be done with Queen Vashti for failing to obey the order of King Ahasuerus?” One advisor said, “It is not against the king alone that the queen has sinned, but against all the ministers and all the nations in all the provinces in all the kingdom, because word of the queen’s deed will reach all the other women and it will make their husbands contemptable in their eyes. The women will say, ‘King Ahasuerus commanded that Queen Vashti be brought before him, yet she did not come!’ And the aristocracy will talk, and there will arise much contempt and anger. So, if it please the King, let there be issued a royal edict saying that Queen Vashti may never again appear before King Ahasuerus, and let the King confer her queendom upon another woman who is better than she. And the King’s proclamation will be heard throughout the kingdom, and all women will respect their husbands, from the important people to the not-important people.”

That’s it. That’s all we get from the Book of Esther.

But Talmudic commentary expands upon the text, interpreting the narrative. Some commentary seems very invested in demonizing the non-Jewish Vashti, to contrast her with the perfection of her Jewish successor. Some declares that Vashti, a shiksa, actually SUPER DUPER LOVED to dance naked, and the only reason she didn’t want to do it this time was that she had leprosy. Or suddenly grew a penis. Or was too busy oppressing her Jewish female slaves.

This very week, the Forward ran an op-ed not at all hyperbolically titled “Actually, Feminists, Vashti Was the Harvey Weinstein of Persia,” which wagged a finger at “ostensibly progressive folk” wrongheadedly celebrating “a vicious anti-Semite and serial abuser of women, crowning her a liberated icon.” This interpretation of Vashti, the piece claimed, “ignores an entire corpus of Jewish thought and, indeed, a rich oral history” concluding “The truth is that Queen Vashti was a sexual predator who used her position to abuse Jewish women.” Truth!

As a kid studying with super-Orthodox rabbis, I was never quite clear on the difference between truth and story, Torah and Talmud, documented history and passed-along folklore. Today, I’m comfortable viewing the act of interpretation as an ongoing process. In 1895, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a First Wave feminist, wrote in her Women’s Bible, “King Ahasuerus was but a forerunner of the more modern lawmaker, who seeks the same end of male rulership, by making the wife and all property the possession of the husband.” Pretty resonant in today’s era of battles over women’s bodies and autonomy, no? To me, that interpretation works better with the actual text than the Vashti-grew-a-tail one, but who could argue that Stanton didn’t have her own interpretive agenda?

Stanton also commented, “Probably Vashti had had previous knowledge of the condition of the king when his heart was merry with wine…Vashti is conspicuous as the first woman recorded whose self-respect and courage enabled her to act contrary to the will of her husband.” Sounds great, but check out that “probably.” It’s supposition. And Stanton’s applauding Vashti’s actions as “womanliness assert[ing] itself and begin[ning] to revolt and to throw off the yoke of sensualism and of tyranny,” younger feminists may be brought up short. Who today would equate sensualism–“the persistent or excessive pursuit of sensual pleasures”–with tyranny? Nice slut-shaming, Liz! (And while we’re talking about problematic faves, don’t get me started on Stanton’s views on race.)

Our culture, experiences, and worldview invariably inform our reading, And our writing, too: Vashti didn’t get any lines in the Book of Esther; generations of female commenters didn’t get to weigh in on classic texts. Vashti can serve as a perfect canvas for all kinds of beliefs, prejudices and wishes. Which is fine. Filling the world with a wide variety of stories, and being willing to re-examine classic ones, makes the world more interesting. And ultimately, we can hope, more just.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.