The Quiet Resistance of Queen Esther

Unlike the brave women in modern-day Iran who protest against wearing the hijab, Esther had to play a subtler game

Didn’t have time to read the Megillah this Purim? No worries! To celebrate the holiday, we asked five writers to reflect on the story’s five leading characters. Missed the previous installments? Click here to read about Ahasuerus; here to read about Vashti; and here to read about Mordechai.

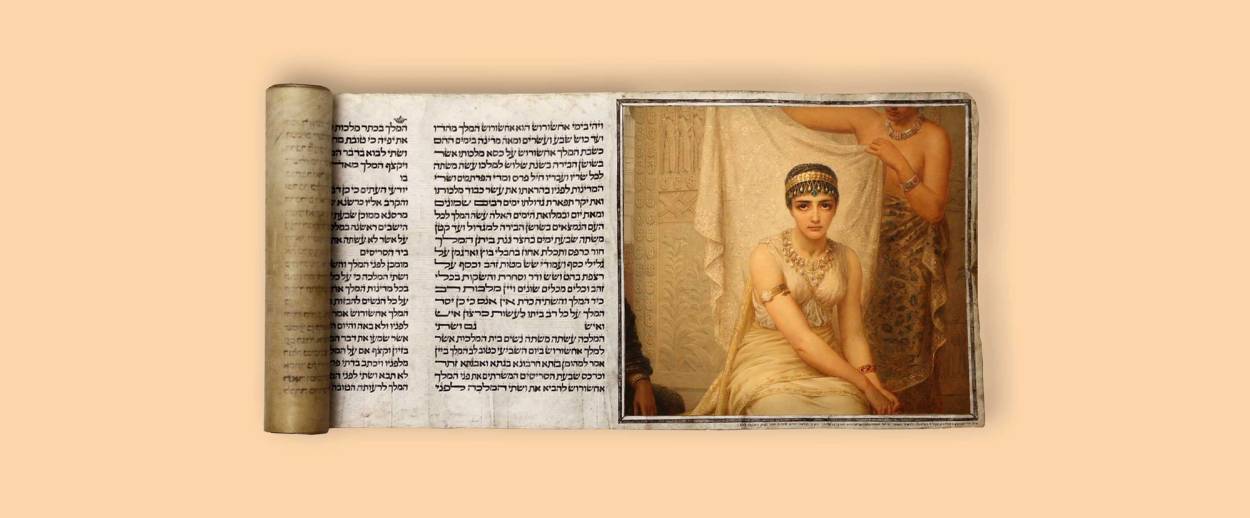

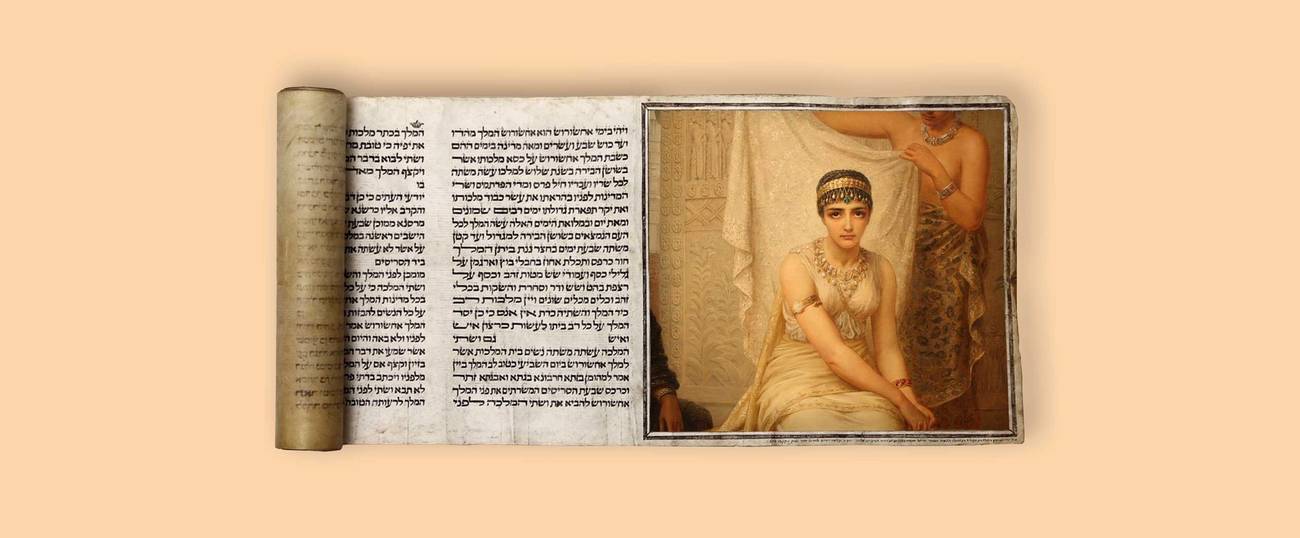

Esther spends most of her time in the Megillah doing as she’s told.

First of all, entering royal custody was not a volunteer position, and she’s essentially drafted into the life of a concubine. And from there, we see her resist the will of others very little. She keeps her Jewishness a secret from the king because Mordechai tells her to do so. She embarks on her mission to save the Jews of Persia at her kinsman’s behest. The Megillah even insinuates that she did not win the king solely on her own merit; the keeper of maidens, Hegai, takes a liking to her and advises her how to approach Ahasuerus.

This isn’t to say Esther does anything wrong; if anything she’s being smart (not that we hear much of what she’s thinking). When you’re neck-deep in a patriarchal society, sometimes you have to play by its rules. And certainly, risking her life took a great deal of courage, when Esther’s husband is the patriarchy incarnate, and subject to violent whims.

Women in Iran, where Esther’s story takes place, are currently bravely protesting the mandatory hijab. But would Esther have been able to rally the maidens of Shushan in some sort of feminist revolt? Obviously not. And you can’t argue with her results; by the end of the story, society has inverted and the oppressed minority of the Jews has risen to the top (for women, it seems, not much changes).

Esther at the end of the Megillah is much bolder than when we meet her; the king grants Esther power, and she suggests the Jews go on a vindictive killing spree, which he approves. She seems to operate as a team with Mordechai, and perhaps, finally, have some ideas are her own. But she’s now operating within the old system of power. Those who wield it may be new, but not much else is.

While she tends to be a favorite female Biblical character (only she and Ruth get books of the Tanakh named after them, after all), she’s also frustrating. She is largely reactive rather than active, accepts the control of men, and we get little insight into her inner world. Pretty much the only time she shares an opinion we can take as read is when she tells Mordechai she fears for her life in approaching the king. When Esther finally seems to exhibit some agency (maybe), it’s with the same violence and power that would have made her a victim. It’s morally a pyrrhic victory.

For good or ill, Esther is a woman of her time.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Despite the handicap of the Bible representing a distinctly male perspective, the Tanakh is full of vibrant, strong, interesting women. There’s Naomi, and Michal, and Miriam. Even the matriarchs argue, or scheme, or take matters into their own hands.

There’s no question; Esther is a hero. Through charm, patience, and politic, she saves her people and stays on top. But she is not a hero of the moment. What we need today, at least in this country, are women (and other oppressed folks) who are loud, who are impolite, who are angry.

What Esther is is a sign of how far we’ve come. You don’t have to play by the oppressor’s rules anymore to win the day, but we’re only here because we’re standing on the shoulders of those who understood that sometimes, survival is victory.

But next step, we’re going the Yael route and cracking skulls.

Gabriela Geselowitz is a writer and the former editor of Jewcy.com.