The (Yeshiva) Basketball Diaries

In light of YU’s historic appearance in the NCAA Division III finals, remembering my own days playing hoops for the Mighty Mites

Of course I kvelled. How could I not? Yeshiva University’s basketball team had made it to the NCAA Division III finals. I am not only an alumna of the school: I was also captain of both the Yeshiva University High School basketball team (then known as BTA, or Brooklyn Talmudic Academy) and the college team now known as the Maccabees (then known as The Mighty Mites, but more on that later). Even though they lost the first game of the playoffs, it is quite an achievement for the underachieving basketball program. And it’s definitely good for the Jews. You can imagine how proud I felt.

I moved from Ramat Gan, Israel, to Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, as a five-year-old. We lived down the block from a fenced-in park next to the boardwalk and the beach. My friends from the park attended PS 253 while I went to the Yeshiva of Brighton, where I had an entirely different group of friends. During summer vacation, I’d hang out with my park friends and shoot hoops from morning till night, but when school started in September we’d go our separate ways and I’d repeat the pattern each year.

One of the great Jewish basketball stars of that era also came from Brighton Beach. David “Shorty” Newmark walked into the park one day with his little brother Brian. They’d both go on to play for Columbia University. Head-and-shoulders above the crowd, Shorty would grow to be 7 feet tall and have a storied career that took him from Lincoln High School to the NBA with the Chicago Bulls, the Atlanta Hawks, and, finally, to Tel Aviv. For a year we played together on the Yeshiva of Brighton team and it feels like we won every game. He could hardly play then, but as they say in basketball, you can’t teach height.

On Sunday mornings, we’d have to wait for the “big guys” to finish playing. That’s what we called those who aged out of the park but still showed for the weekly game. They had a regular run, fiercely battled full court games where every possession mattered because losing meant waiting your turn to play again. So many players had “next” that it could take more than an hour to get on the court again. Mark Reiner, already a star at NYU, would show up and dazzle with his ball handling and ability to shoot with either hand. I’d study his moves and try to replicate them.

At first the idea of nice Jewish boys playing any sports at all was cause for suspicion of one’s priorities. It was considered something foreign to Jewish culture. The subject came up at the Second Zionist Congress in 1898, where the concept of “muscular Judaism” was discussed and debated: Could “strong and physically fit Jews defeat the classic stereotype that Jews are physically weak and instead depend solely on their wit”? By the 1950s, the answer seemed to be a resounding yes, with Jews like Abe Saperstein, who founded the Harlem Globetrotters in the 1920s, and famed basketball coach Red Auerbach, proving that in a sport like basketball, revolving around teamwork and movement, Jewish smarts were an asset. Even modern orthodoxy seemed to have made its peace with basketball—YU’s team was established in 1933—and yet, my own family did not.

My basketball-crazy summer friends were my first contacts outside the confines of my survivor family mentality, one that preferred limited contact with non-Jews or even Jews deemed not religious enough. On Shabbos afternoon—when my grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins and their friends assembled in the park for their Shabbos schmooze—I’d be playing full court. When I saw them starting to arrive, I’d slowly slink away, my yarmulke tucked into my back pocket, heading for the anonymity of Coney Island.

High School was a step up in my basketball education and appreciation. The coach was Irv Forman, and the school was part of The Metropolitan Jewish High School League that played a competitive schedule against other Yeshivas like our arch enemy Flatbush, Ramaz, Hebrew Institute of Long Island and MTA our sister school in Manhattan. Unlike my teammates who had learned to play by competing with other yeshiva kids, I had more of a street game that stood out from the others. I started on the varsity as a freshman, played back court, and averaged around 17 points per game. We won the league championship on the floor of the old Madison Square Garden when high school games used to open for the Knicks.

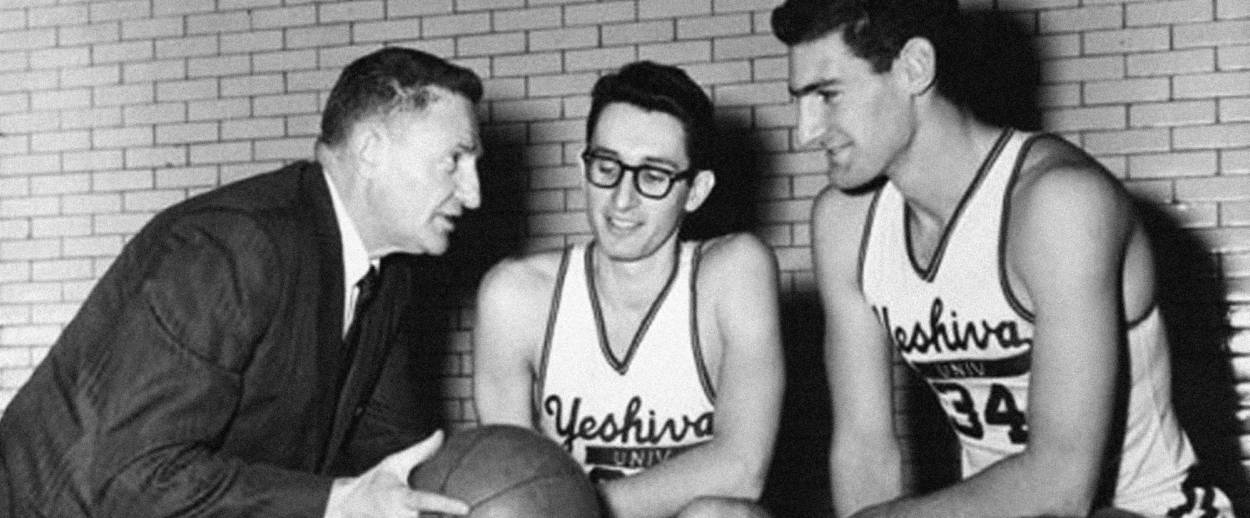

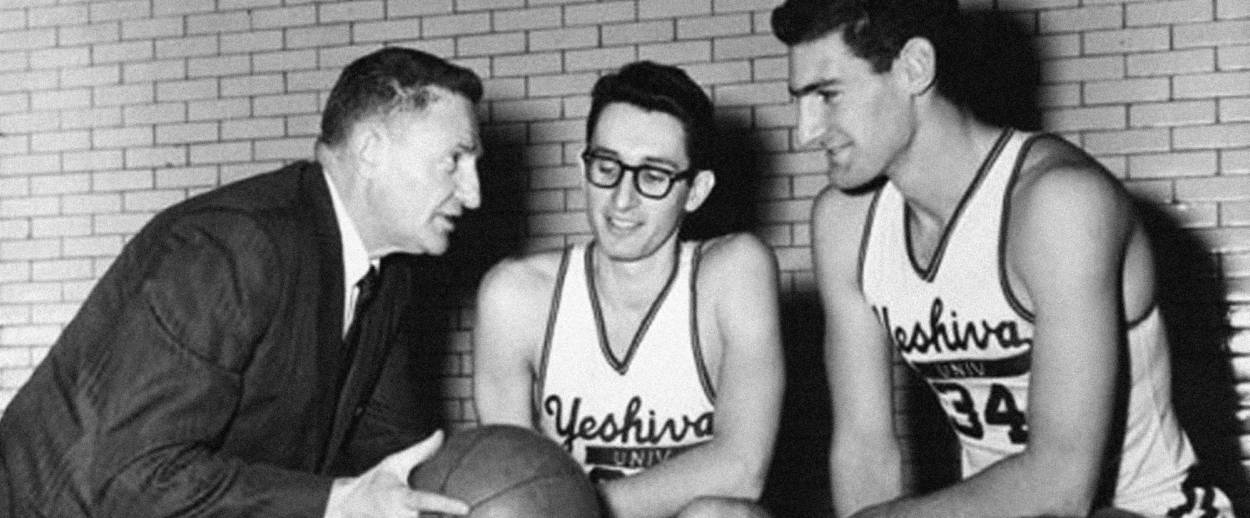

And then came time for college. Columbia, NYU, and UMass had all rejected me, and I was resigned to go to Brooklyn College, not far from my home, where I would know people and possibly play on the basketball team. I spent the summer at Camp Morasha, which had a team that played other camps under the watchful away of Marvin Hershkowitz (no relation), a former Yeshiva University basketball legend who had seen me play in high school when he was the coach of our rivals, Ramaz. He was a macher at the camp, and arranged for me to work in the kitchen as a pot washer, mostly so I could play on the camp team. One day he asked me to meet Red Sarachek, the highly respected Yeshiva University basketball coach, who had driven up for the day. He was buddies with Knicks’ coach Red Holzman and St. John’s Lou Carnesecca. No less trusted a source than Wikipedia says that Yeshiva, under Sarachek, has been called “the birthplace of modern basketball due to Sarachek’s innovative ball-handling schemes. Sarachek designed and implemented motion offenses, trapping defenses, plays to beat zone defenses and creative in-bound plays. His schemes were admired and copied by coaches around the country.”

Whatever prevailed upon him to bring his sophisticated basketball mind to a bunch of physically challenged yeshiva boys in a man’s world is beyond me, but that he did, giving the team a stature it didn’t quite deserve. He was gruff, self-effacing, and charming in social settings, but when running a practice or coaching he was a beast of a different order. He’s one of those guys who would have to severely temper his rhetoric to survive in today’s politically correct climate. Several players, who couldn’t take the verbal abuse, left during my four years, but there was something about him that demanded respect that I still give him today. He seemed old, though now that I do the numbers I realize he was only 55. He gave me a sales pitch on Yeshiva, said I would probably start, and offered me a scholarship. A divinity deferment, a 4D, beckoned, which would give me virtual immunity from the selective service and the Vietnam War, was mentioned as a possibility. For my father, this closed the deal. He had survived the holocaust and fought in Israel’s War of Independence. Though he was scrupulously honest, his experiential instincts prevailed. He’d do anything to keep his son out of harm’s way.

As a freshman, I was fully into the program, giving it my all in practice and fighting for rebounds against the team’s formidable all-star senior, Shelly Rokach. We’d practice on Thursday nights, and he’d sometimes offer to drive me home from Washington Heights to Brooklyn after practice. He lived, not far from me, in Boro Park. The subway ride would take more than an hour and a half, and I looked up to him as the team’s star player so I went. He also had a reputation for being wild, which became evident as soon as he got behind the wheel of his car. We set off towards Brooklyn, his V-8 roaring, speeding, barely touching the brakes along the treacherous West Side Highway. By the time we’d reached the outskirts of Boro Park, he had attracted the attention of the police who, sirens blaring, gave chase. A big smile on his face, I can still remember how he leaned back, one hand on the wheel, turned off his headlights like they do in the movies, made a couple of quick turns, and lost them.

As we got deeper into the 1960s, the smell of weed and the cries of the anti-war movement had made its way to the reaches of Washington Heights. My father had uncharacteristically bought me a Ford Mustang, which was meant, I have only recently learned, as a present to make up for making me go to YU. I had moved out of the dorms and had an apartment nearby I shared with three other students, all of us disgruntled and feeling out-of-place in the religious environment. Everyone was talking about San Francisco then, and Scott McKenzie’s “When You Go San Francisco Be Sure To Put Some Flowers in Your Hair” was a big radio hit. When Time magazine came out with their “Summer of Love” cover they had me. Make Love Not War? Sounds like a good option to me. I recruited two friends that summer and off we went on a cross-country trip that would change the course of my life.

Finding my Nirvana in San Francisco, I didn‘t want to return to school, but my friends insisted I was suffering from a type of temporary insanity brought on by my San Francisco psychedelic experience. I returned but with a different perspective, enlightened and radicalized, a protester who went to marches and stayed up late at night listening to WBAI reporting on the movement. I wrote for a school countercultural zine that started up guerrilla style and go to the Electric Circus on St. Mark’s Place in the East Village where Lou Reed’s Velvet Underground was the house band and report on what it was like being in a multimedia experience known as the “Exploding Plastic Inevitable.”

As for basketball, I was as committed as ever as an escape from my otherwise oppressive Yeshiva environment. Though Coach Sarachek would bully and berate, at least I could get to travel and I still loved to play. My commitment never wavered—only my motivation did. After my cross-country trip and missing a summer of workouts and scrimmages, my progress had stagnated in a critical year for college ballers whose summers are typically spent getting bigger and stronger playing with coaches at basketball camps.

As a freshman, I was a team mate of Johnny Halpern who followed Sarachek as coach for the next 25 years. When I was invited to a breakfast to celebrate Halpern’s retirement, I decided to go even though I had absolutely no interaction with the school since graduation. I recognized some familiar faces and we reminisced about how when we played the school didn’t have a gym. Because of Sarachek’s connections, we’d practice mostly at Catholic Schools including St. John’s University and Power Memorial High School where we played our home games. Kareem Abdul Jabbar, then known as Lou Alcindor, played at Power and went on to become the nation’s number one High school recruit. (He enrolled in UCLA and led them to many championships before going to the NBA and doing the same for the LA Lakers). I still think about how awkward the setting was, looking up at a giant crucifix hanging behind the backboard each time I took a foul shot.

We were known as the Mighty Mites, not the Maccabees of today. The team was renamed in the 1970s, perhaps with the intention of changing the script on its fortunes. Noted Jewish sports scholar and Yeshiva University History Professor Jeffrey Gurock diplomatically describes my years as one when the team “struggled against athletically superior squads.” Yeah, we didn’t have the best record but we were scrappy and had the best coach though his era and his patience had run out and he retired a few years later.

I’ve passed on the basketball gene to my son, and my whole family has come along for the ride. Funny how the ball bounces. Inspired by YU’s divisional basketball championship, it occurred to me to write this personal essay. Basketball at first took me away from my roots, and now it has taken me full circle.

David Hershkovits is the founder and editor of Paper magazine.