The Problem with ‘Wild, Wild Country’

The show’s lack of interest in Rajneeshism as actual religion makes it incoherent

Like any effective work of art, and like the Bill Callahan song whose lyrics it’s named after, the Netflix documentary Wild, Wild Country sticks in the mind. In the story of the Rajneesh Movement’s conflict with its neighbors in the Oregon backcountry and its subsequent (or possibly already well advanced?) descent into paranoia, electioneering and um, biological terrorism, directors Maclain and Chapman Way chose a topic that splays into nearly everything imaginable. Since finishing the six-hour Netflix documentary a week ago, the Rajneeshees and their failed early 1980s utopia have intruded upon my more mentally idle moments: Wild, Wild Country is about the myth of the redemptive powers of the American landscape and the often-dangerous fantasies that people project upon the mystically vacant land. It’s a study in charismatic authority, and in the people who fall for and in some sense even need that authority. It’s also as gripping a cops-and-robbers true crime story as you’re ever likely to watch.

But the Ways missed something big, and one of the most fascinating tensions suggested in Wild, Wild Country is explored in disappointingly little depth (spoilers ahead, insomuch as one can spoil the outcome of a real event that happened over thirty years ago). The film confronts viewers with two possibilities: Either Bhagwan Sree Rajneesh and his “secretary” Ma Anand Sheela are psychopathic scammers who marshaled astonishing powers of manipulation and the thin veneer of religion to extract money, labor, and devotion from thousands of spiritual seekers—or the Baghwan was someone with a coherent theology and worldivew who commanded devotion because of the force of his ideas and vision, rather than his adeptness at committing fraud. Viewers are never really given enough information to evaluate this question, because Wild, Wild Country, a six-hour film about a real-life religious movement, is weirdly uninterested in religion itself.

What do the Rajneeshees really believe? Other than some sinister and almost comically non-systematic late 1970s gibberish from the Bhagwan about creating a “new man” forged from Eastern spirituality and Western reason, viewers don’t really get much. Sheela is openly contemptuous of religious practice: “Meditators, we don’t need,” she sternly recalls of the early days of building the Oregon compound, which is perhaps the first religious community with a fleet of Rolls Royces and its own casino. The question of why a religious movement would need Rolls Royces and casinos—and the related question of how it would go about acquiring such things—is one at which the film only briefly glances.

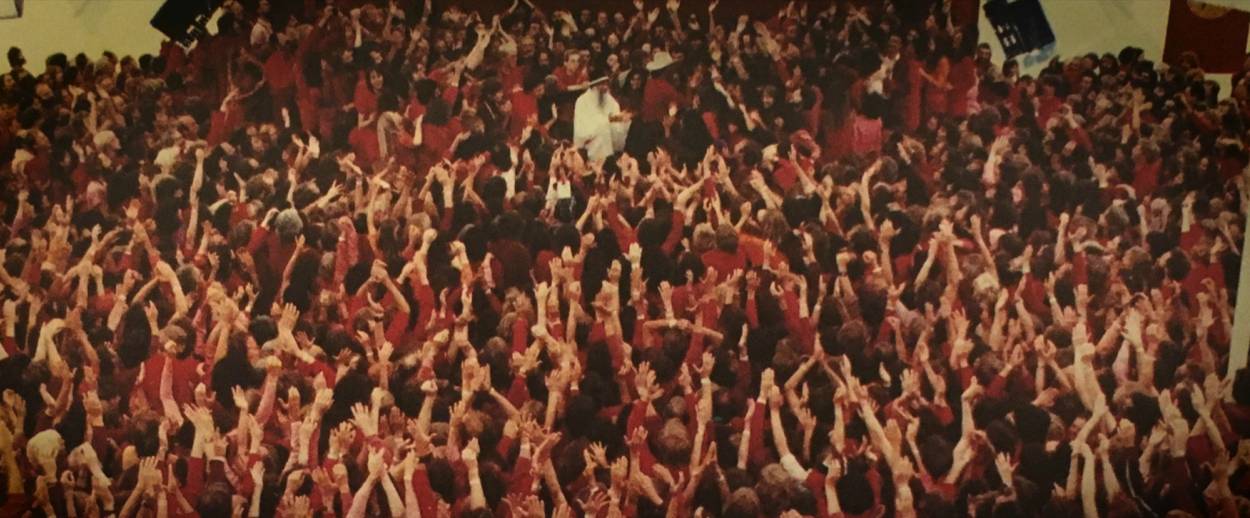

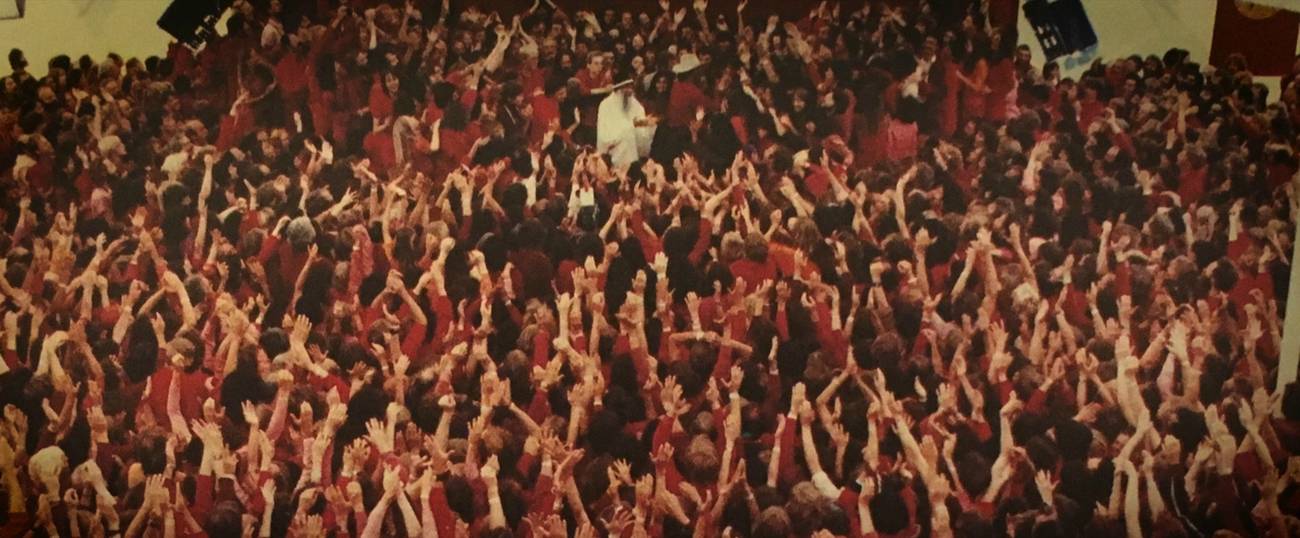

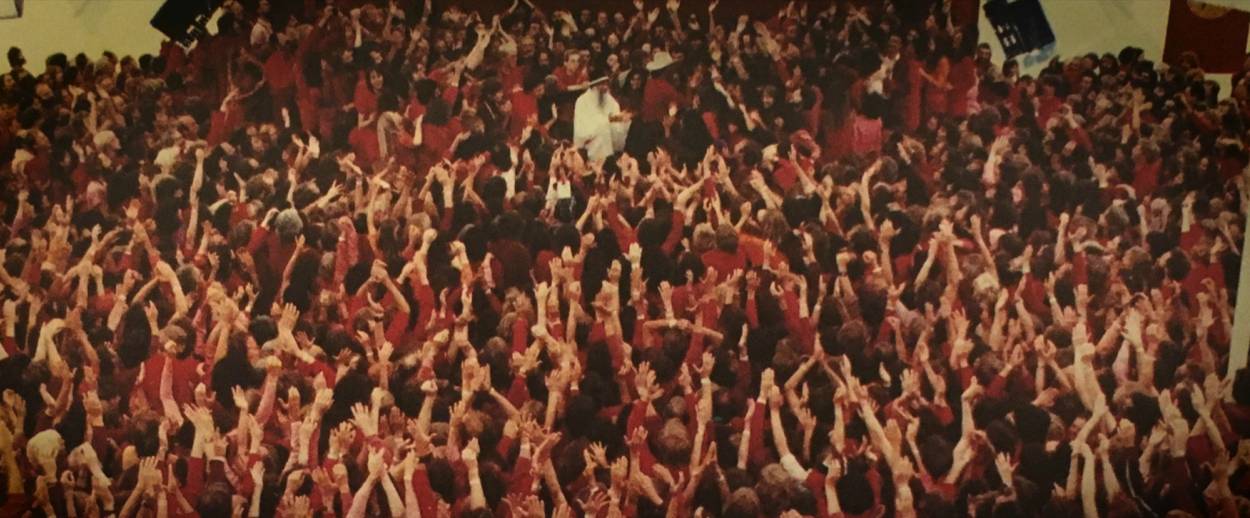

If there’s an underlying theology to Rajneeshism, viewers will have to learn about it on their own. But then again, Rajneeshism is an inexact term, because in 1985 the Bhagwan decreed Rajneeshism over and ordered the ceremonial burning of the sect’s prayer books and doctrinal texts: “For the first time in human history, a religion has died!” the Bhagwan declares as thousands of followers spasm in spiritual ecstasy at his every word. But why?

One could leave Wild, Wild Country with the impression that the Rajneeshees really only believed in doing whatever the Bhagwan and his inner circle commanded them to do: He tells his followers what to wear and whom to marry, and they listen to him (although it isn’t mentioned in the documentary, he also forbade them from having children, and they listened to him about that too). There are practices in Rajneeshism, but they involve a traumatic-looking version of meditation that requires jumping and screaming, along with possibly also orgies—again, viewers don’t get much to go on. One critical data-point: Sheela shows no interest whatsoever in religious belief or practice or any higher ideals of any kind, although her dedication to Rajneesh is undeniable.

The we’re-a-religion, we’re-not-a-religion bait-and-switch isn’t even the most sinister mind-game that the Bhagwan inflicted on his followers: He went four years without making any public statements, which had the probably intended effect of creating factions competing for his love and attention while also releasing his flock from the responsibility of having to believe in much of anything, period. On his deathbed in India, the Bhagwan told his personal lawyer to write a book clearing his name in the United States, something this man has apparently spent the last three decades doing, partly as an act of personal gratitude—in a sense, the Bhagwan controls him from beyond the grave. After the Bhagwan flees the Oregon compound to avoid his impending arrest, the community rapidly collapses and dies, simply because of the departure of a single individual. But again—why?

The question of what the Rajneeshees believe isn’t a trivial one. If Rajneeshism was an actual faith, then Wild, Wild Country is a story of how the dynamics of religious extremism can assert themselves even (especially?) within vibrant and largely peace-loving enclave cultures. If Rajneeshism is a cult or a grift, then the documentary is a story of how easily the trappings of religion can be used to control massive numbers of people. The answer probably lies somewhere in between, but because the documentary largely avoids the entire topic of practice and theology, this question is hard to negotiate without additional research beyond the scope of what is, again, a very long film. At times, the project’s lack of interest in religion actually makes the movie narratively and dramatically incoherent.

Why didn’t a pair of obviously brilliant filmmakers recognize this, and why did they have so vast a blindspot on a topic so fundamental to their work? For religious people, religion is obviously about doing things and believing things. Between prayer, study, and various other obligations, a religious Jew might spend hours each day absorbed in theologically-rooted actions and activities. Within other faiths, religion is similarly treated as the junction of doing and believing: “Religion and faith consists of sayings and actions: the sayings of the heart and the tongue, and the actions of the heart, tongue, and limbs,” the 14th century Islamic thinker Ibn Tamiyya decided; Saint Augustine wrote of heaven being “stretched over us like a skin,” as if the spiritual nature of all being were akin to an ambient reality that a believer never has the option of avoiding.

Either the Ways found themselves unengaged by a major plank of their subject matter, or they didn’t think that viewers in 2018 would really care about the substance and occasional tedium of religion, even in the context of a documentary that’s about exactly that subject. Wild, Wild Country is an astonishing feat of filmmaking. But it’s also just the latest example of how alienated and incurious much of American society is regarding matters of faith, even when the topic is staring right at them.

Armin Rosen is a staff writer for Tablet Magazine.