In recent months, Twitter has taken to removing its blue check mark “verification” badges from racist figures on its platform, from alt-right luminary Richard Spencer to Islamophobic troll Laura Loomer. Originally, the badges were simply meant to denote that Twitter had verified a user’s identity, especially if they were a public figure. In practice, however, the appearance of a coveted check mark next to a user’s name conveyed a certain status to them, and even led less savvy readers to believe that Twitter had offered the account its personal stamp of approval. For this reason, Twitter began taking the badges away from far-right racists.

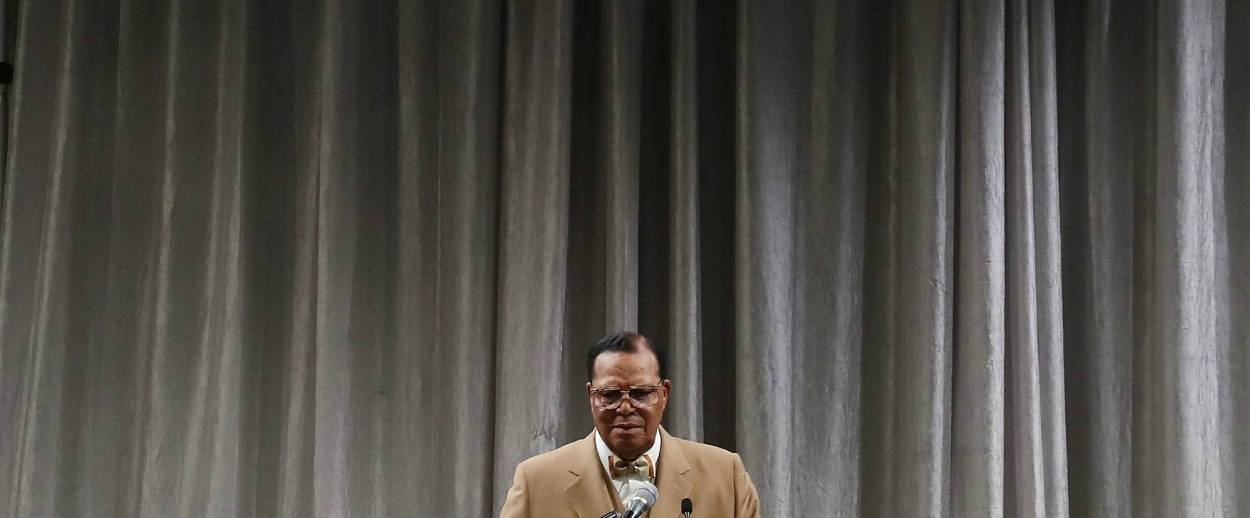

When this process began in November 2017, Tablet’s Liel Leibovitz pointed out a particular figure on Twitter eminently deserving of such defrocking: Louis Farrakhan, the hateful cult leader who has blamed Jews for everything from 9/11 to the slave trade, among many other vicious libels. The Nation of Islam leader regularly uses Twitter to mainline anti-Semitism and other bigotry to his nearly half a million followers. Finally, this past week, Twitter took action after a particularly egregious rant from Farrakhan:

Shortly after my tweet above, the company removed its verification badge from Farrakhan.

Some might wonder, though, if this goes far enough. After all, if there was ever a case for banning someone from Twitter for hate speech, it would surely implicate Farrakhan. But as a general rule, Twitter has opted not to silence even its most extreme voices, whether Richard Spencer or Farrakhan, unless they directly threaten violence or abuse. And I would argue that at least in Farrakan’s case, this is actually a good thing.

Why? Because erasing hate from social media doesn’t make it go away, it just makes it easier to ignore. When Farrakhan and his supporters are out and about on Twitter, racking up retweets, getting tens of thousands of video views, and spreading bigoted calumnies, it makes it much more difficult to dismiss them as inconsequential, as so many of their apologists have attempted to do.

When Women’s March organizer Tamika Mallory was exposed as a long-time supporter of Farrakhan and promoter of his work to her followers, her critics were often told that he wasn’t actually significant, and that the right was simply using him as a tool to distract from their own (very real) bigots. This evasion enabled Mallory’s defenders to avoid confronting Farrakhan and his enablers like her without explicitly owning up to it. They never did explain why, if Farrakhan was indeed so inconsequential and powerless, Mallory and others—including the many members of Congress who had met with and even praised him—were so reticent to denounce him. Had Twitter simply disappeared Farrakhan from its platform, however, the fiction of his insignificance would have been easier to maintain.

A similar case played out in 2012 in France, when a viciously anti-Semitic hashtag became the third-most trending one on Twitter in the country. After being threatened with a lawsuit by well-meaning activists, Twitter removed the offending tweets. But of course, this did not put a dent in the problem of anti-Semitism in France, and years of brutal and violent attacks on Jewish targets followed. In reality, the hashtag was a warning that was swept under the rug. It exposed anti-Semitism and made it unignorable—until it was made invisible.

Simply put, disappearing anti-Semitism from social media conceals a symptom, thereby making it easier for people to ignore the source. Few people are converted to racism by a bigoted 280-character tweet, but many people can be made aware of the racism’s existence by seeing one. The answer to online bigotry, then, is not to hide the evidence, but to use it to raise consciousness.