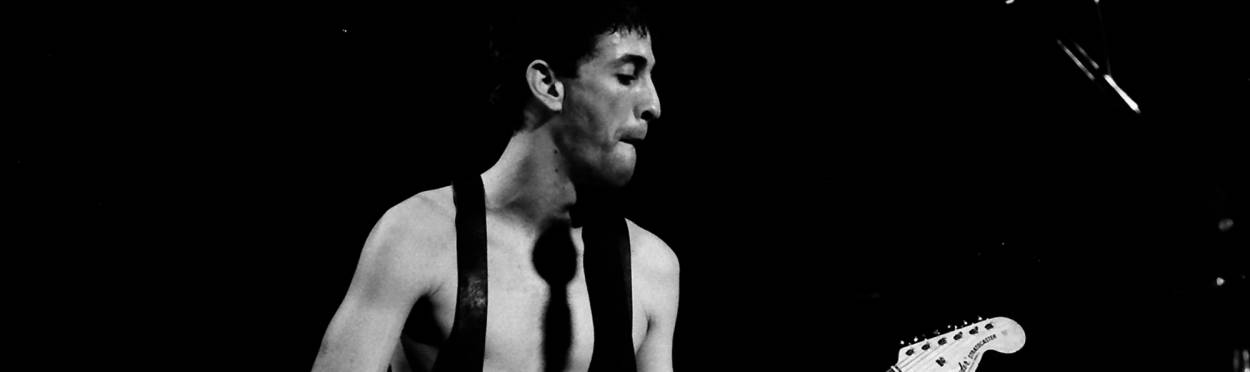

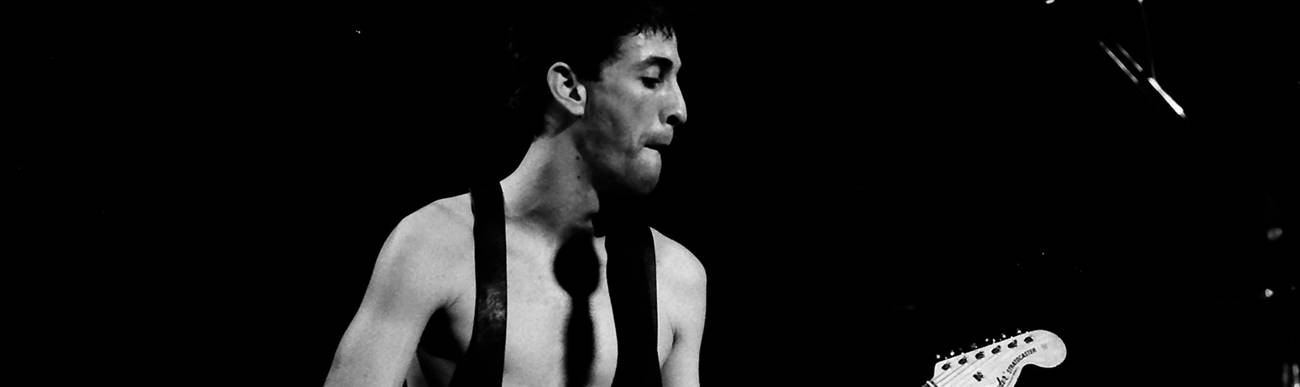

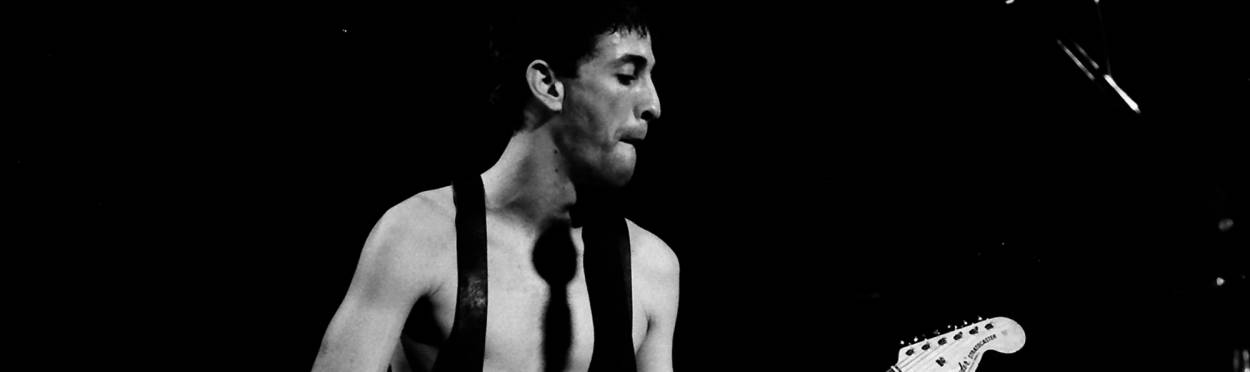

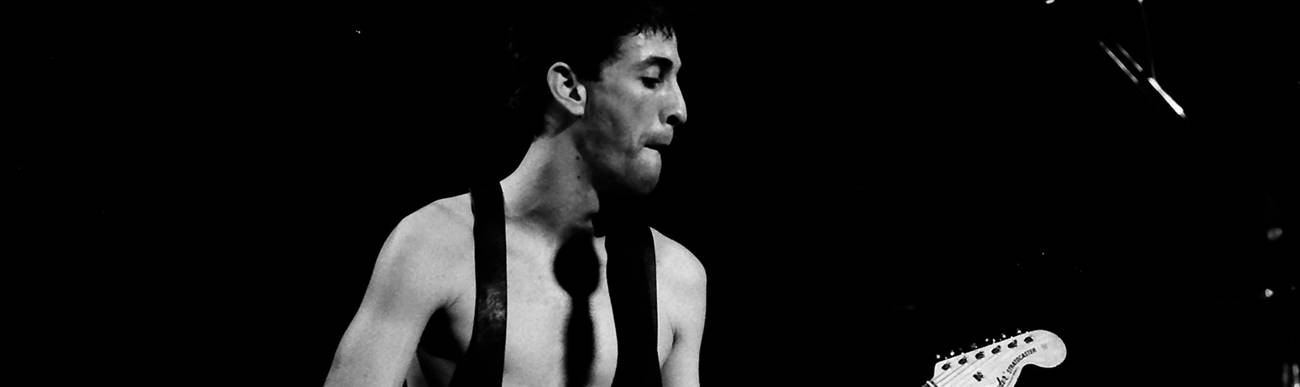

Remembering Hillel Slovak, the Forgotten Founder of the Red Hot Chili Peppers

The Israeli-born guitar hero died 30 years ago today

A small group of my friends grew up in the South Bay of Los Angeles, the locus of punk and a music scene I came to learn about well into adulthood, which is probably a good thing because I don’t think I could’ve handled it as a youngster. I grew up on grunge, punk’s younger, pudgier cousin, which provided a different and perhaps calmer type of adolescent music therapy. Grunge was imported to suburban Massachusetts from Seattle; punk thrived in their backyards—in Hermosa Beach, in Orange County, on Sunset Strip. Grunge felt like a sensitive, chorus pedal-driven world closed upon itself; punk, as my L.A. homer friend put it, was “fast, loud, derivative, and unthoughtful,” a back-in-the-day lo-fi experiment that has evolved into some “say whatever I want, man” present.

When I think about how music influenced my youth, and then how it influenced my friends, I feel a sense of awe—as though I’m looking into an alternative mirror of what my life would’ve been like had I gone through puberty a coast away. Whereas I dyed my hair green and rode a mountain bike and played football and listened to Alice in Chains and Pearl Jam and Stone Temple Pilots and Soundgarden, my L.A. buddies friends dyed their hair blonde and surfed and skateboarded and listened to Black Flag and Descendents and Redd Kross and Minutemen. I was an outsidery New England Jew with a spidey sense for the emotional instability developing inside of me, the likes of which were soothed by Layne Staley and Jerry Cantrell’s hardcore harmonies. In the stories I tell myself, my L.A. friends were beachy minipunks with a semi-false sense of toughness who could shred anything stringed.

Back in New York we’d often sing karaoke together. Sometimes we’d incorporate themes—bad songs only, dead singers only, Elton John only. The stupid fun you have when nobody is looking. Our tastes would often overlap, which makes sense as bands like Nirvana and Rage Against the Machine and Weezer ruled the airwaves in the 1990s and transcended, in a sense, “the rock genre.” One song they never fail to sing along to, typically when the night is closing in, is “Under the Bridge,” the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ most commercially successful song, which is not very punk, no not very punk at all, in theme or in theory or in melody. And I love watching them sing it.

“Under the Bridge” might never been recorded had it not been for Rick Rubin, the producer of Blood Sugar Sex Magik, the band’s fifth album. (In fact, Blood Sugar Sex Magik is the first album laid down at The Mansion, Rubin’s famed recording studio in Laurel Canyon.) You see, Rubin had discovered a poem written by Kiedis in the singer’s notebook. He was enamored by it and asked Kiedis to sing the words. Reluctantly, he did. “It knocked [Rubin] out,” Kiedis recalled just months after the album was released. “I didn’t even want the band to hear this song, but when they did, they were floored by it.” Thanks in part to the accompanying music video, “Under the Bridge” would catapult the Red Hot Chili Peppers into superstardom.

One might call “Under the Bridge” a rock ballad, something in the vein of Guns ‘N Roses’ “November Rain,” at least in terms of its structure and emotional tapestry. Ultimately, however, “Under the Bridge” is a song about friendship and love and loneliness; drugs and redemption; and Los Angeles, the city of angels that watched over Kiedis during the two decades he had lived there to that point—and a time during which he had periods of heavy drug use, including from before the time he had even hit his teens.

Recalling his inspiration for the song, Kiedis said, “The only thing I could grasp was this city. I was driving away from the rehearsal studio and thinking how I just wasn’t making any connection with my friends or family, [and] I didn’t have a girlfriend.”

“And Hillel wasn’t there.”

***

Hillel Slovak, the original guitarist for the Red Hot Chili Peppers, died of a drug overdose at the age of 26. That was 30 years ago today, so it’s high time we remember and appreciate the Israeli-American guitarist whose influence reverberates throughout the Chili Peppers’ canon. Even in 2012, during the band’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Kiedes called him the band’s “heart and soul” and “architect.”

The original members of the Red Hot Chili Peppers—Kiedis, Slovak, Flea, and Jack Irons—came together at Fairfax High School in Los Angeles, although most of them had first met at Bancroft Junior High. Slovak and Kiedis would become fast friends, and in Scar Tissue, Kiedis’s excellent 2004 biography, co-written by larry “Ratso” Sloman, he recalls the first day they spent together, as friends, noting Slovak’s sense of self, calm demeanor, and musical intelligence. “I immediately knew that Hillel was at least my equal,” he wrote.

Slovak also introduced Kiedis to a particular slice of life. “Hillel was Jewish, he looked Jewish, and talked about Jewish stuff, and the food in that kitchen was Jewish. He made us egg salad sandwiches on rye bread that day, which was totally exotic food to me then.” (Irons, it should be noted, is Jewish as well.)

Slovak was born in Haifa in 1962. His mother, Esther, was a Polish Holocaust survivor, and his father, who was from Yugoslavia, also survived the Holocaust. They fled to Israel during World War II and met on a kibbutz there; Slovak’s older brother is named James. When Slovak was four years old his family eventually found their way to Queens and finally settled in L.A., which is where Slovak received a guitar for his bar mitzvah. Recalled his mother, “Hillel used to play everywhere— in the garage, in the bedroom, even on Passover Eve. Every person who heard him play said he plays like Hendrix.” (It appears that Esther Slovak may have died earlier this year in L.A.)

The Chili Peppers performed for the first time in Israel in 2012, with Flea declaring in the middle of the show that Slovak “invented Israeli punk.” The words “Hillel, We Love You” were brandished onto screens and Kiedis even dedicated “Around the World” to Slovak’s hometown of Haifa.” Onstage Flea recalled a trip Slovak had taken to Israel during his late teens. “He was so lit up and so excited and so full of love.”

The Red Hot Chili Peppers, whose early beginning did not yet include Kiedis, have cycled through a number of guitarists. But in almost every interview with the band I’ve watched or read, Slovak’s creativity was a guiding light for the band’s growth. John Frusciante, who would replace Slovak as the band’s guitarist after his death—he would go on to record five albums with them before enjoying a varied and somewhat prolific solo career—idolized him. In fact, Flea has said that he would’ve never started playing the bass unless Slovak had taught him how to play the instrument. (As a kid Flea had actually wanted to be a jazz trumpet player as he idolized Dizzy Gillespie.)

Count me among those who first got into the Chili Peppers as a kid when Blood Sugar Sex Magik came out—my cousin lent it to me and I never gave it back—and then again when I read Scar Tissue while overseas, gasping throughout the book at Kiedis and Slovak’s addictions to heroin and cocaine, which they both fought numerous times—a battle that Slovak tragically lost. (Prior to their Tel Aviv stop, Adam Chandler wrote about Kiedis’s absence from Slovak’s funeral because he was strung out, which he sings about in “This is the Place” from 2002’s By The Way: “On the day my best friend died/I could not get my copper clean.” He described one emotional visit to Slovak’s grave at Mount Sinai Memorial Park Cemetery in Hollywood Hills, in Scar Tissue, during which he refers to his friend as “Slim” and weeps and weeps, promising him to stay clean.)

But apart from “Higher Ground” and “Knock Me Down” off Mother’s Milk, I’d heard nada from the band before their breakthrough album. What a shame. Over the last few weeks—my L.A. friends would be proud of me—I’ve been listening to Freaky Styley (1985) and The Uplift Mofo Party Plan (1987), the band’s second and third albums, which Slovak was an active and integral part of, as well as Mother’s Milk, which is just fucking awesome. In fact, Slovak left the band prior to its first album to focus on his main music project What is This?, before returning to RCHP to the joy of Kiedis and Flea. In honor of Slovak, take a few minutes to listen to his contribution to the Red Hot Chili Peppers, one of the greatest living bands.

Freaky Styley was produced by George Clinton (the Atomic Dogfather himself!), with much of it being recorded in Detroit. The group did tons of cocaine while making it.

The Uplift Mofo Party Plan was recorded in Los Angeles, at the Capitol Record Building in Hollywood. “It was so fun [to make]” Slovak wrote in his diary, which was released in book form (along with his artwork) after his death: “I’m so extremely proud of everybody’s work [on Uplift], it is at times genius.” Numerous songs on the album are about him, including “Skinny Sweaty Man,” performed here in 2000 with Frusciante.

At the time of the album’s recording, Kiedis was in and out of rehab. During the tour to promote the album, Slovak was struggling mightily with his own addiction to heroine, and he had to sit out a few shows during the European leg of the tour. But the album, and the footage from those times, shows a band deeply in love with their musical chemistry at the time—a band growing in real time. The video below is a compilation of footage of Slovak from the 1988 RCHP documentary Europe by Storm. When asked about the band’s silliness and what it stands for Slovak says, “It stands for spontaneity. On tour, a lot of ridiculous anarchistic—something we do—it’s just a release because on tour is a very good place to build up a lot of strange energies. And they’re usually good strange energies. Sometimes their kind of mysterious strange energies.”

Slovak would play his final show with the band on June 4, 1988 in Finland. The final song he played live was a cover of Hendrix’s “Fire.”

Jonathan Zalman is a writer and teacher based in Brooklyn.