‘Crossing Delancey’: A Pickle Seller’s Love Story Turns 30

Looking back 30 years later at the Lower East Side romance

Comedian Jenny Slate is fervent in her love of Crossing Delancey. In interview after interview, she calls it one of her favorite movies. “I first saw this movie when I was a little girl,” she told Rotten Tomatoes (where the film is rated 91% fresh). “I was so drawn to Amy Irving, her personal style in this film. I loved this story of a progressive, intelligent, Jewish New Yorker who was so bonded to her grandmother, but not necessarily to her cultural traditions. And what a great romance! There is nothing else like this movie.”

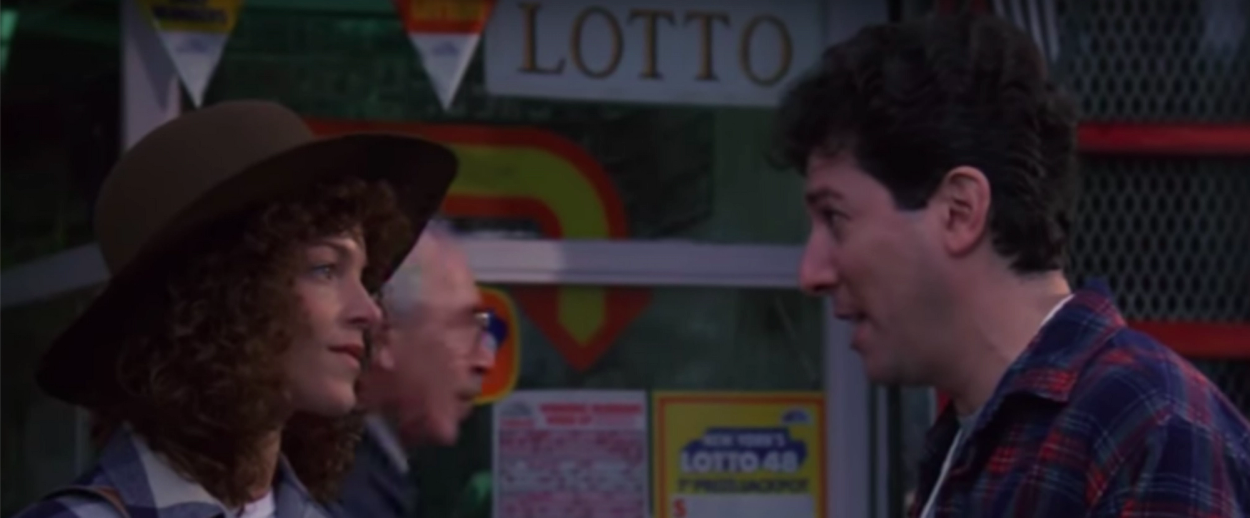

Amen to that. In Joan Micklin Silver’s underappreciated 1988 classic, Izzy (Amy Irving), in a succession of fabulous loose outfits blending Annie Hall and velvet-y proto-East-Village boho, runs an uptown reading series for an independent bookstore. She regularly heads downtown, though, to the Lower East Side, to visit her savvy, snarky Bubbie (Yiddish theater legend Reizl Bozyk, in her only film) in Seward Park. Izzy leads a full life: She’s a literary tastemaker; her boss adores her; she is in possession of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s unlisted phone number; she has great, funny female friends and a rent-controlled Upper West Side apartment. And she kills her own spiders. But Bubbie frets about her granddaughter’s single state (“She lives alone in a room, like a dog!”) and hires a matchmaker (played by the voracious, hilarious, slightly terrifying Sylvia Miles) to find Izzy a man.

Bubbie is bullish on Sam, a haimish, plain-speaking pickle vendor (played by the soulful Peter Reigert). Izzy, horrified by the yenta-ing, lusts for Anton, a hilariously pretentious author (played to bedroom-eyed perfection by Jeroen Krabbé). Izzy waffles between Anton’s worldly, seductive wiles and Sam’s persistent, non-games-playing interest and ability to listen. (When Sam sends Izzy a clever, pointed gift, she tells her grandmother, “Bubbie, I’m being wooed.” Bubbie replies, “Vood? Vas is vood?”) The audience knows Anton is a total jerk because he orders Izzy a hazelnut tart without asking her what she wants, or whether she wants dessert at all, and then, as she tries to tell a story, loudly talks over her and leans over to eat off her plate. Schmuck.

Ultimately there’s little doubt who Izzy will choose. But the journey — Susan Sadler wrote the script, based on her own play produced at the 14th Street Y — is delightful. It’s full of images of the old Lower East Side: Signs in Yiddish, the crumbling storefront of Schapiro’s Wine,an ultra-Orthodox boy eating a pastry straight from a Gertel’s Bakery box. The sweet, poppy, fizzy yet melancholy harmonies of the Roches wind through the soundtrack, along with bits of RUN-DMC and The English Beat. Rosemary Harris holds court as a literary grande dame, expertly skewering a seething Anton over and over during a salon at the bookshop. Stick around for the credits and learn that some of the other party guests are actual literary lights: Lore Segal, John Patrick Shanley, Susan Braudy, Hendrik Hertzberg, Keith Reddin.

Crossing Delancey feels suffused with female energy, putting women’s concerns first, and it’s simultaneously sharp and affectionate. One of Izzy’s bookstore colleagues hosts a public-access cable show; we see a snippet of her with one of her guests, a performance artist played by performance artist Pat Oleszko, dancing in a bodysuit covered with dozens of groping arms and Mickey-Mouse-type white gloves, while chanting “Getcher hands off her, getcher hands off her, getcher hands off her.” There’s even a reference to the Guerilla Girls. Izzy’s relationship with her grandmother is beautiful and tactile: Izzy plucks chin hairs, rubs baby oil into aching knees. It’s like a Yiddish Mary Cassatt painting, with more depilation. You can’t take your eyes off Irving, with her luminous skin, clouds of curls, and still, watchful expressions.

You can’t watch the film today without feeling loss. Where there once were dozens, now there’s only one Lower East Side pickle vendor. (An amazing one, but still.) Schapiro’s (“the wine you can almost cut with a knife”) became a hipster restaurant run by Israelis, then closed entirely. Gertel’s left the neighborhood in 2007; there’s an anonymous wholesale factory in South Williamsburg. Crossing Delancey felt like an elegy when it came out; it feels even more like one now.

It’s also a movie that points out the urgent need for more female film critics. Women adore this movie. Men often find it uninteresting, simplistic. In his review, Roger Ebert called the plot “the usual stuff” and rolled his eyes at Izzy’s conviction that she’s “part of the scene.” How is she so clueless or in denial of “the fact that some men, on one level or another, are thinking of sex when they talk to a pretty girl, no matter how they may flatter her intelligence”? Ebert also got a major plot point wrong, meaning there’s a huge spoiler early in his review. Damning with faint praise, Hal Hinson at the Washington Post observed that “the filmmaker’s heart is in the right place” and called the film’s charms “highly perishable.” But Janet Maslin at the New York Times praised Crossing Delancey’s “warm and leisurely” pacing, and the way it manages “to combine a down-to-earth, contemporary outlook with the dreaminess of a fairy tale.” Sheila Benson at the LA Times compared it to Moonstruck, calling it “at once hip and romantic; wittily sophisticated and unabashedly affectionate; a love poem to all New York and a companion piece to director Joan Micklin Silver’s Hester Street” (in which Carol Kane provided the Irving-esque luminosity, and was nominated for an Oscar). Crossing Delancey almost didn’t get made at all; Silver had a hard time getting financing until Steven Spielberg, then Irving’s husband, offered to approach Warner Brothers himself. Plus ça change, as they say in Yiddish.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.