Fenway Park’s Mystery Music Man

Bieber, free jazz, prog rock—Fenway organist Josh Kantor provides the score for the grand drama of Red Sox fandom

The chimes rang out across Fenway Park at 6:24 p.m. as the last few Red Sox and Astros stretched out their pregame jitters and fans trickled in from Landsdown and Ipswich Street. The soundtrack echoing through the stadium mere minutes before the most pivotal game of a 108-win season was the closing 10 minutes of side one of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells, a sublime and ridiculous prog odyssey recorded in 1973.

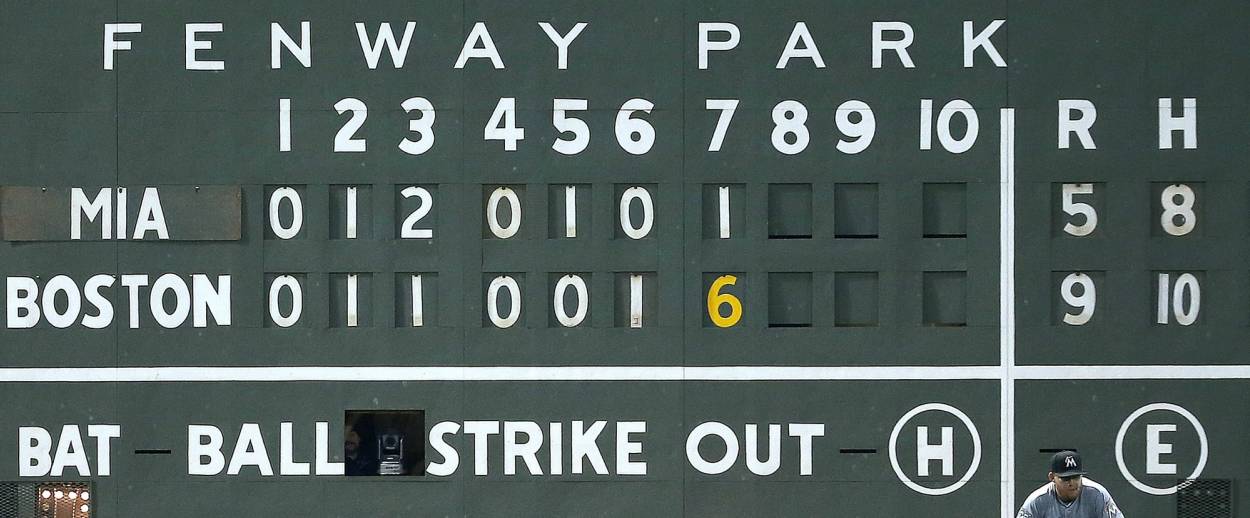

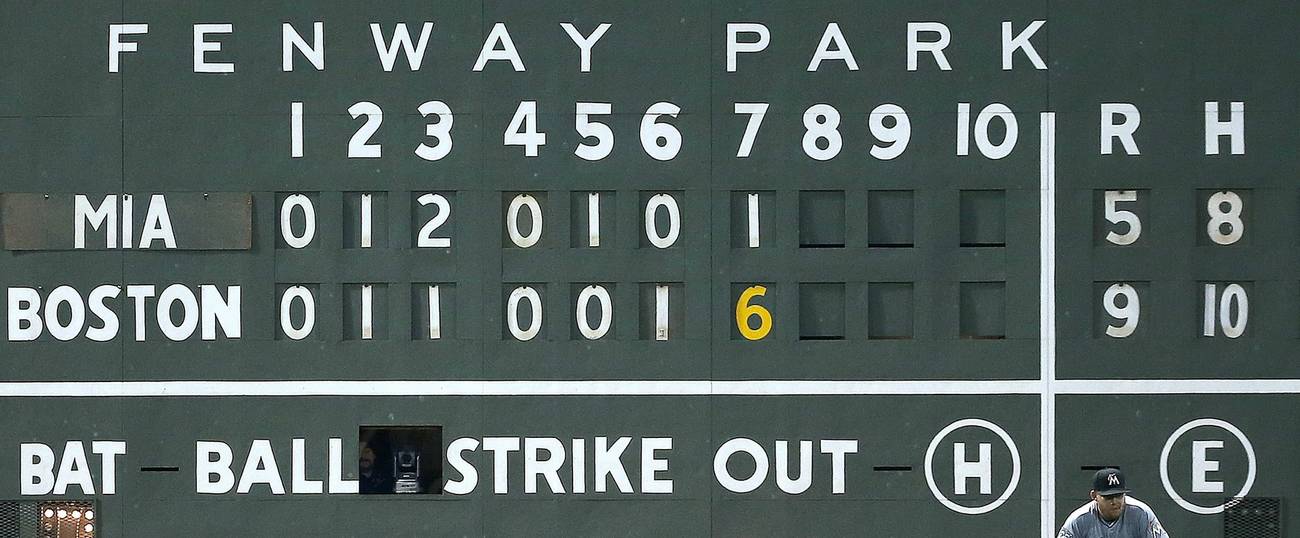

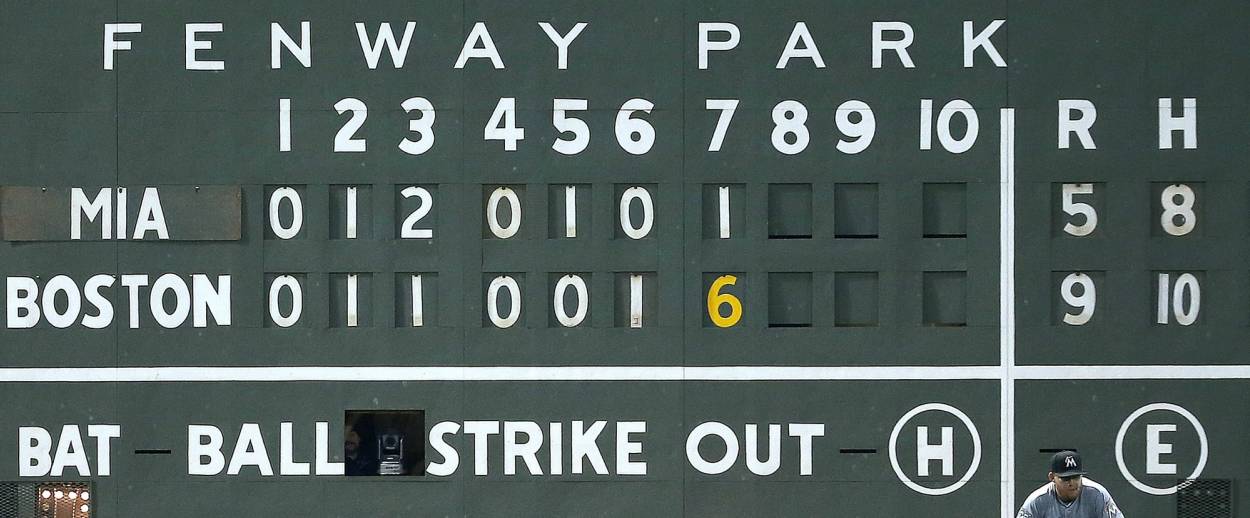

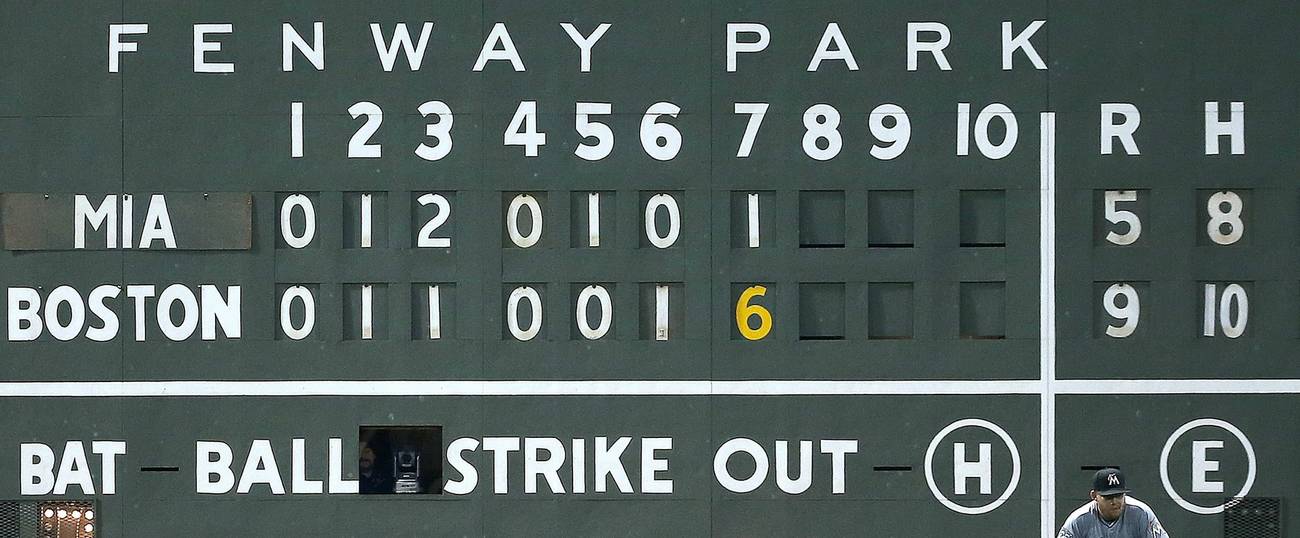

Glockenspiel played as the American League finalists jogged across the outfield. The defending World Series champs were trying to extend their 1-0 series lead over the home team in a best of seven series. By the time the distorted guitars and Spanish guitars rolled around the last glimmers of natural light had disappeared behind the Citgo sign. This was an exhilaratingly weird sonic entree to game two, in which Boston’s season hinged on the lefty David Price, one of the dominant pitchers of his era as well as one of its more baffling postseason head-cases.

Fenway feels and even sounds different than every other park, perhaps because Boston is one of the few cities whose spirits can still hinge on the outcome of a baseball game. Josh Kantor, Fenway’s organist since 2003 and one of the architects of the park’s strange and wonderful soundscape remembers that before game 4 of the team’s immortal 2003 American League Championship Series comeback against the Yankees, “There was a lot of doom and gloom just in the air around town. And it was hard to escape that.”

The gloom promptly lifted back in ‘04: A little over a week later, the Sox had overcome a three-game series deficit and then swept the Saint Louis Cardinals for their first World Series championship in 86 years on the strength of a slugging David Ortiz, a bleeding Curt Schilling, and some positive thinking from the organist’s booth. “I just told myself as I got to the ballpark that if you walk in that gate it means you firmly believe they’re going to win tonight,” Kantor remembered of that ALCS game 4, a 12-inning heart attack clinched with an Ortiz homer. Kantor knows that he doesn’t have much impact on the team’s success on the field but after 16 seasons he recognizes his power to guide things along. “Most games [the crowd] requires very little additional encouragement from myself or from the DJ because Red Sox fans are intense by nature,” Kantor observed. The organist “can kind of help steward that journey a little bit.”

Fenway is one of the rare stadiums where that journey—or what’s come to be known as “the ballpark experience”—is still primarily baseball-based. The fans are crammed into the century-old grandstands to watch their team play, a radical concept in this day and age. There is often no music between pitches or batters, and therefore few distractions from the aspects of the sport that the modern-day live baseball consumer has practically been conditioned to ignore. Like much of the rest of the crowd at Fenway, Kantor, who has witnessed some 1,300 games from his perch above home plate, pays attention to what’s going on off the ball. “You can sort of see everything and focus in,” Kantor said of Fenway, which he described as “old and cramped and small and intimate.” “You can see what’s happening when the batter steps out of the box and the catcher flashes the sign and the pitcher’s looking in and the outfielders are adjusting where they’re playing because now it’s a 2-1 count so the guy’s more likely to pull the ball.”

The Sox and Astros traded leads in the first three innings, and Price and Houston starter Gerrit Cole settled down after a thrillingly erratic opening third. At the end of the 4th, with the Sox clinging to a 5-4 lead on the strength of a bases-clearing Jackie Bradley shot to deep left, Kantor tapped out an uptempo rendition of “Baby”—Twitter-user @FeministDonut got her wish for “some old school Bieber.” The Strokes’ “Reptilia,” another Twitter ask, translated nicely to organ—the instrument softened the tune’s zig-zagging guitar riff without the song losing steam. “The litmus test for learning a song on the organ is if can you hum the melody,” Kantor said. A few seasons earlier, he’d played a song by the often-unhummable free jazz visionary Sun Ra after a Twitter request. Not anyone’s idea of ballpark fare, but Kantor found a way.

Kantor is the organist of record for the greatest stretch of Red Sox success in the team’s post-war history, with the war in reference of course being World War I. Tonight, he will play in his fourth World Series, which is the same number of appearances the Sox tallied during the entire period spanning from 1919 to 2003. A Brandeis graduate, avid record collector, Stevie Wonder enthusiast and library assistant in Harvard’s law and music collections, Kantor thinks of a baseball game in the same terms as improvisational theater, which he live-scored in his pre-Fenway music career. “It’s the same idea where you have players on the stage and you don’t know what’s gonna happen next and you have to be ready to respond with the right idea or to drive the thing forward or to underscore it or to react.” Losing streaks demand numbers that are neither overly funereal nor inappropriately upbeat—The Replacements’ “Here Comes A Regular,” for instance — and a big Sox home run often requires getting out of the way entirely. Another stop on the road to Fenway was the bima of the renowned cantor Jeff Klepper, who Kantor backed on piano during shabbat services in high school (Klepper and Kantor are still friends, and played together at a baby naming this past Sunday).

Like Fenway itself, the ballpark organ hearkens to an ideal, primordial vision of the game, one where every contest was a matinee, every Sunday had a double-header, relief pitchers barely existed, and everyone would be in and out of the ballpark in a crisp two-and-a-half-hours. This nostalgic idyll also mostly sucked in reality. The game was hideously racist, as was society in general. Players were locked into contracts they couldn’t escape and star hurlers were worked into obsolescence by their mid-20s. The technology to blast something as situationally odd and perfect as Mike Oldfield during pre-game warmups simply didn’t exist yet and for several decades the organ was the primary method of filling gaps in the action. Today, the contemporary ballpark organist is one of several people who’s there “to put together a live audio-visual production.” Kantor is in constant communication with the DJs and scoreboard operators, speaking in a clipped control room-code that allows everyone “to say the thing you need to say before the next pitch happens.” For Kantor, the ballpark organ is nostalgic and dynamic: “I think for a lot of people it represents an era of baseball that has a lot of positive connotations but is maybe only partly connected to what the game looks like nowadays.”

The introduction of pop music into the ballpark organ repertoire began with one of Kantor’s major influences and mentors. Kantor went to high school in the Chicago area, where he heard White Sox organist Nancy Faust in action, a musician “widely regarded as the best sports organist that’s ever been.” As Kantor explained, Faust began playing at Sox games in the early 70s, when she was 23 years old. “She knew all these current hits whereas a lot of the organists were older and came more from the Broadway tradition or the Tin Pan Alley tradition or the Great American Songbook.” Kantor has the advantage of being able to access any song online as soon as someone requests it. Faust, who performed for 41 mostly internet-free seasons, needed no such assistance. “She could hear a song on the radio while she was driving to the ballpark and then she could play the song that night when she got there,” said Kantor.

Nearly the entirety of all music is at Kantor’s fingertips, as it is for the rest of us, too. Kantor estimates that he’s performed more than 700 unique songs over the 81 home games of the past regular season, which comes out to almost nine a game, which comes out one per inning or three every hour. Twitter requests become reality in rapid cycles. He’s constantly performing “a sort of base-60 mathematical division of ok, this chorus is eight measures and I’ve got 30 seconds left so I need to play the chorus twice at 128 beats per minute.” Songs have to be compressed or elongated on the fly. “You don’t want to end it in sort of a weird nondescript part of the song so you either cut that part altogether or save that for somewhere in the middle—but you hit people with something big at the beginning and at the end.” He watches the clock counting down the two minutes and thirty seconds between innings, a recurring series of near-instant deadlines.

“It’s almost like a parlor trick at this point, this idea that I can listen to a song and then I can play it back for you usually on one listen,” he said. “It’s like being a parrot, you know. I don’t necessarily know what I’m saying. Like if you say a sentence to a parrot and the parrot says it back the parrot isn’t communicating, it’s just mimicking. So I have this ability to mimic.”

Part of Kanator’s talent lies in performing mimicry that doesn’t sound like mimicry. In the late innings of game two, there was a groovy “She Moves in Mysterious Ways”—Kantor had the fans over in the Section 38 bleachers dancing along to one of the more inscrutable of the popular rock numbers, although with the Sox clinging to a three-run lead and the temperature plunging almost no one was sitting down anyway. The organist, framed with a headset and a thick salt-and-pepper beard, smiled to the crowd from the jumbotron during the seventh inning stretch, during which he was introduced by name. In the top of the 9th, Jose Altuve, Houston’s diminutive superstar second baseman, plunked an RBI off the Green Monster in left field. Up came Alex Bregman, who had walked three times that evening and suddenly represented the tying run. The 7-5 Red Sox victory was sealed with a terrifying pop fly that nearly reached the warning track—the team would close out a 4-1 series win just days later but with three games to go in Houston there was no guarantee the home team would return to Fenway before April of 2019. Kantor played Green Day’s ambivalently upbeat “When I Come Around” to an emptying stadium of lingerers, souvenir photo-takers and grounds crew. Next was a bouncy one that sounded melodically similar “Daydream Believer” but turned out to be Dean Martin’s “(Goin’ Back to) Houston.” After that, silence—Kantor got the last word before the plane ride west or the jubilant walk back to the T, and his organ mingled with “let’s go Sox!” chants as fans squeezed through the the outfield concourse and back out into the cold.

Armin Rosen is a staff writer for Tablet Magazine.