The Lamps That Burned for Thousands of Years

A new exhibit at the Jewish Museum explores Hanukkah lamps through the ages, from gold and silver to acorn shell and pomegranate peel

Odds are good that you have never heard of Dr. Harry G. Friedman, the Polish born and New York raised rabbi, investment banker and philanthropist. If you visit the new Hanukkah lamp exhibit at the Jewish Museum in New York, however, you can’t miss him; his name and influence are everywhere.

Of the 30,000 objects in the permanent collection of the Jewish Museum, where I work as a docent, about 6,000 of them came from Friedman. For more than 20 years, during and following the Second World War, he scoured New York’s antique and consignment shops, in search of Jewish ceremonial objects. What he found he bought and donated to the museum in the hope future generations would see and be moved by what they represent.

In an exhibit that opened on November 26th, Accumulations: Hanukkah Lamps, almost half of the 81 lamps on display came from Friedman. How could it be otherwise? Almost two-thirds of the 1,050 lamps in the Museum’s permanent collection, the largest collection of Hanukkah lamps in the world, came from his efforts and his discerning eye.

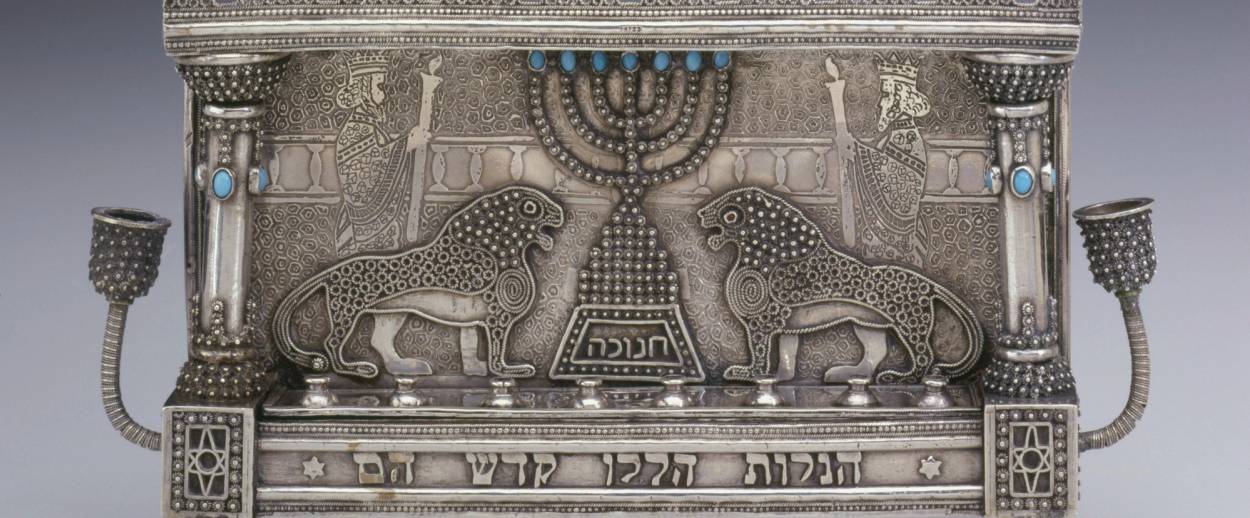

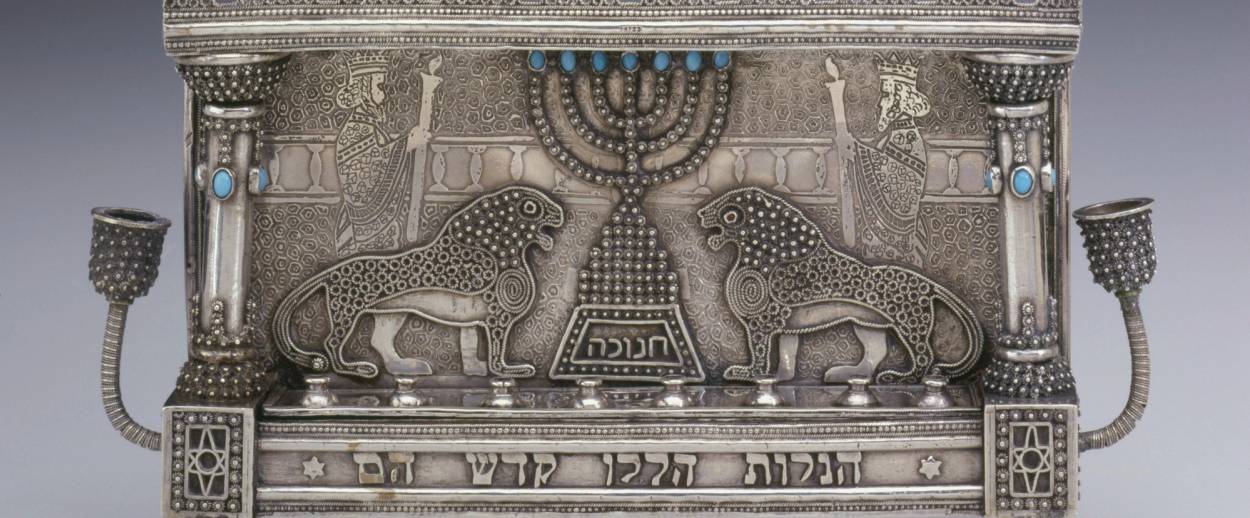

Look for the silver lamp from 18th century Nuremberg, Germany, with a parchment insert listing the Hanukkah blessings, made by non-Jewish silversmith Matheus Staedlein. Friedman donated it. So, too, the early 20th century silver and semi-precious-stone lamp from the silver filigree workshop at the Bezalel School in Jerusalem, the large copper alloy lamp for synagogue use from 18th century Galicia, and the stoneware lamp made in Germany in 1807. His donations run the gamut from the finest materials to the most pedestrian.

Curator Susan Braunstein organized the lamps on exhibit by material. She followed the dicta of the rabbis in Talmudic times who instructed their followers to construct their holiday lights from the most precious materials they could afford –gold to silver to brass, 15 categories in all, ending in pomegranate peel, walnut or acorn shells. Friedman’s donations span almost every category, save the pomegranate, walnut, and acorn which have not withstood the test of time.

Some of the lamps on display at first blush make no sense, like the large wooden Hanukkah lamp, not from Friedman’s collection. Why burn candles in a wooden lamp? Jews in Theresienstat, a concentration camp established outside of Prague in 1942, had no choice. Wood was the only material they could get their hands on. And the sculptor, Arnold Zadikow, and wood carver, Leopold Hecht were determined to make a Hanukkah lamp for the children in the camp. They knew the value of history and the importance of finding a way to observe a holiday whose rituals celebrated their people’s perseverance.

The same was true for Friedman. The greater significance of the objects lovingly hauled from one continent to the next was not lost on him. According to Braunstein, Friedman, “considered it his mission to salvage Jewish ceremonial and fine art wherever he could find it…It did not seem to matter if the piece were homely or if the museum already owned numerous examples of that particular type; all works were considered precious to salvage for the benefit of future generations.”

The lamps in the current exhibition span four continents and represent six centuries of artistic production. Their style varies by region and craftsmen, reflecting the dispersion of the Jewish people across the globe. Together, they are a testament to a people’s tenacity, creativity, to the steadfastness of Jews to hold fast to their history, tradition, religion, beliefs, across time and space. Wherever they go, they find a way to celebrate this “minor” holiday and embrace its symbolism.

Harry Friedman never actually lived in the grand home that is now The Jewish Museum, although odds are good that he attended meetings there. German Jews Frieda Schiff and Felix Warburg had the limestone structure built for their family of seven. Warburg was also a philanthropist, involved in the needs of the community. In fact, both Warburg and Friedman were founding members of The Federation of Jewish Philanthropies, the forerunner of today’s UJA. According to the Jewish Communal Register of 1917-1918, both men sat on the same Religious Education Committee.

And while they didn’t plan out their collaboration—Warburg died a few years before Friedman began collecting—100 years later, they are still working together. Warburg’s home houses the collection to which Friedman contributed so much. Together their efforts protect what came before them, to serve as a beacon for what lies ahead.

Rachel Ringler is a writer, museum docent, challah instructor, and cook who has strong feelings about the important role food plays in life, in family and in community.