Banquo’s Ghost and the Fall of Hungarian Communism

The 30th anniversary of the nation’s liberation is troubled not only by its past but also by its present

This autumn marks the 30th anniversary of the fall of Communism in Central Europe, when in a matter of weeks, those in charge of the one party state were hounded out of power in East Germany and Czechoslovakia, overthrown by an internal coup in Bulgaria, shoved against a wall and shot in Romania, and sent packing after round table negotiations with opposition groups in Poland and Hungary.

I was living in Budapest in the late 1980s, which was considered by citizens of East Germany, Poland, and other Warsaw Pact countries to be as glamorous as western Europe. Unlike the colorless capitals of East Berlin and Warsaw, here was a city on the Danube with huge neon signs winking along grand if soot-covered boulevards, gypsy bands that played in smoky beer cellars, and where in Habsburg-era coffee houses, dessert trolleys piled high with creamed cakes rattled past dazzled, polyester-suited East European tourists. There was even a glitzy pedestrian shopping street crowned with an Adidas shop, where a queue stood before it from morning till night.

Looks were deceiving, though, as Hungary’s economy was a genuine basket case, and although reforms had been tried since 1968, they had only tinkered with the edges of state ownership and weren’t really addressing problems of outdated industries, decayed infrastructure, and a workforce that didn’t seem particularly keen on working, even while hundreds of thousands of Hungarians registered for two or three jobs. “We pretend to work,” the expression went, “and they pretend to pay us.”

By the time I moved to Budapest in March of 1988, western companies were being invited to Hungary to look over state industries, and before long, General Electric bought the largest light bulb manufacturer in Communist Europe while West German and Austrian firms began moving in as well. McDonalds also opened its first restaurant in the Warsaw Pact, and before you scoff, think of this: Every employee was told to smile at customers and to be friendly to them. This was an idea so foreign to most East Europeans it was like telling your cat to fetch your newspaper.

I was covering the McDonald’s opening for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in May of 1988, and some 300 people were waiting outside. When the first customer loaded up a tray for him and his beaming son, everyone behind the counter burst into spontaneous applause. I was wondering if a manager was going to rush out and say, well I didn’t mean that friendly.

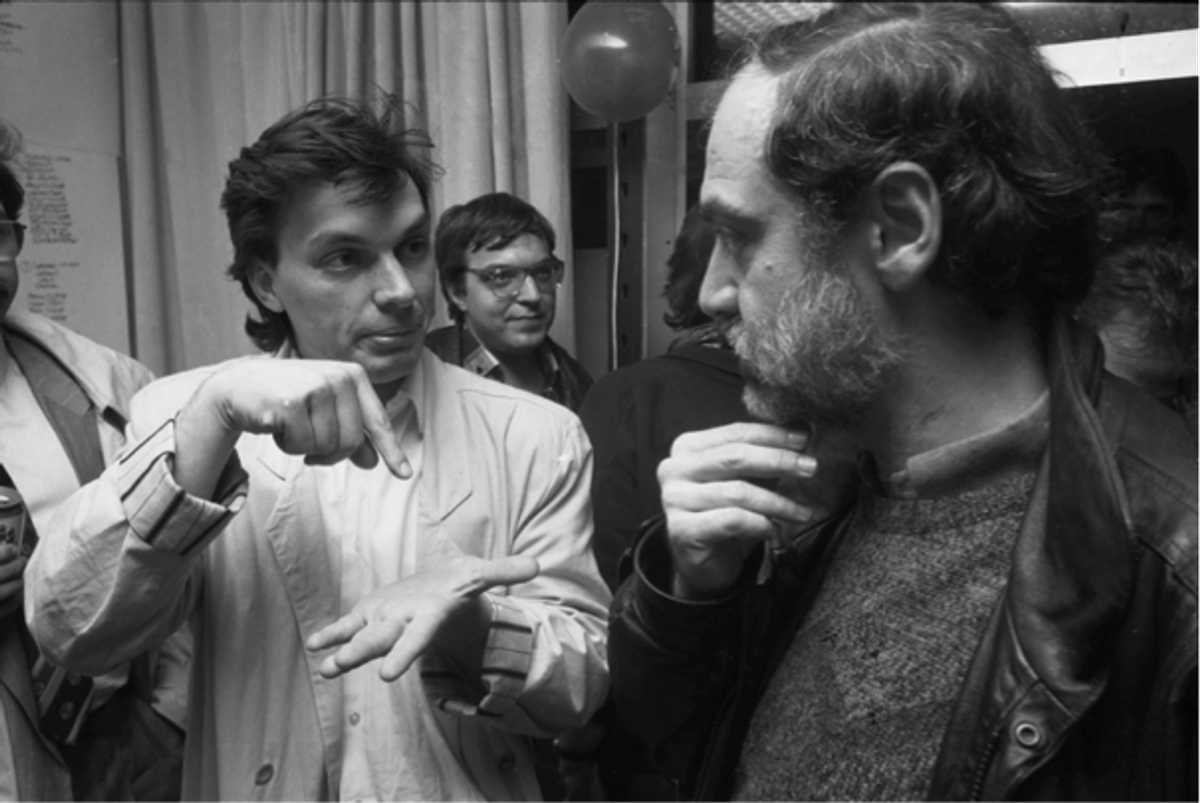

In January of 1989, playwright Istvan Eorsi took David Lewis, the Reuters bureau chief, and me to the city’s central cemetery, as there was something he wanted to show us. We walked through one well-tended section after another until we came to an overgrown potters’ field, known as Plot 301. Three policemen were sitting in a Volga sedan taking pictures of us while I took pictures of them.

Eorsi told us that back in 1956, when Hungarians rose up and literally chased Soviet troops out of the country on October 23rd, a hesitant reformer, Imre Nagy, had been won over by the people’s will, and promised reforms from a balcony of the Parliament. A day later, he was installed as prime minister. On November 1st, Soviet tanks roared back into Hungary, and over a thousand tanks began bombarding Budapest on November 4th. Nagy and his compatriots were hunted down, arrested, tried, and on June 16th, 1958, hung and dumped in the field in which we were standing. Eorsi served three years in prison.

“We literally knew where the bodies were buried,” Eorsi told us. “Every day, the widows of those on trial would stand at the cement fence over there and peer through the slats. When the grave diggers came to bury a body, they would call them over, ask who they were burying, and then mark it down on little hand drawn maps.”

In the meantime, in text books, in the press and in every Communist Party meeting since 1956, Imre Nagy was labelled a traitor and the uprising called a counter-revolution. Not that anyone except the hardliners of the Central Committee believed it.

By early 1989, reformers in the government understood that aside from desperately needed economic and political reforms, something had to be done about Nagy, who, thirty-one years dead, had become Banquo’s ghost—and the Central Committee, like Macbeth—could see his corpse haunting every banquet. Imre Nagy was going to have a state funeral.

The date chosen, not surprisingly, was June 16th, the anniversary of his hanging, and the location would be Hero’s Square in the center of Budapest. A dramatic stage set was designed by the architect Lazslo Rajk, whose own father had been a brutal Communist who sent fellow citizens to the gallows before being hung himself in 1949. In Hungary, it seems, there is always a back story.

Unlike demonstrations I would photograph over the next few months in Berlin, Prague, and Warsaw, no one had come that June morning to celebrate. Here were hundreds of thousands gathered in Hero’s Square, yet it was as quiet as a funeral, which is what it was. Hungarians had come to mourn family members and friends who had been killed, jailed or who had fled the country and were too afraid to return.

After the service at Hero’s Square, the coffins were brought to Plot 301, and I saw a woman standing there, holding a carnation and a snapshot of her brother. He had been killed fighting the Russian tanks in 1956, she told me. “I just wanted him to be here,” she said as tears welled up in her eyes. Later, as I made my notes about who spoke and what had been said at Hero’s Square, the one speech that stood out came from a young firebrand by the name of Viktor Orban, who demanded the Soviet Army leave the country once and for all. A social democratic politician with a future, I thought. Well, I was right about the politician part.

That very week, opposition groups and the government sat around tables and began negotiating how Hungary could become a multi-party democracy, and the negotiations continued through the end of June and into July, then stretched on into August and September.

I attended the Communist Party congress on October 7th, which was attended by well over a thousand members. Listening through the translation I could hardly believe what I was hearing: That Leninism was going out the window, that the party was changing its name to the Hungarian Socialist Party, and it would now become a social democratic party. A large number of true believers split off that day and would re-found a Communist Party. And they would sink into oblivion.

During a question and answer session, one delegate stood up, took the microphone, and spoke about the need for a “social market” economy. A confused delegate on the other side of the hall raised his hand and said, “What the hell is a ‘social market’ economy? You either have a socialist economy or a market economy!”

The answer came back, “Well the Germans and the Austrians both say they have a ‘social market’ economy!”

Everyone turned toward each other, murmured and nodded.

“OK, put me down for that,” and laughter filled the hall. And all I could think was: they really are that naïve, and they really are that willing to change. As it did so often in the second half of 1989, I felt I was in the presence of history being made.

Sixteen days later, on the anniversary when Imre Nagy declared Hungary stood on the balcony of Parliament and addressed the crowd, Matyas Szuros, the acting President, stood on that same balcony of Hungary’s grandiose Parliament and said “As of this date, October 23rd, the state bears the name of the Republic of Hungary.” It would be March of 1990 before parliamentary elections were held and that is when democracy would truly spring to life.

It was just before the March elections that I prepared to leave Hungary to move to West Germany (and that’s a name that vanished a few months later, too). As I packed my car and drove through town, I saw election posters for this party and for that one, and I couldn’t help but think: When I moved here 24 months ago, this was a Communist country. Now it’s a democracy. Then I sped toward towards the border.

I do so wish I could end this article there, but I can’t. The democracy that the opposition parties in Hungary hammered out and established after Nagy’s funeral would last for more than two decades, until that young firebrand, Viktor Orban, now older and far more right wing, attained, for the second time, the prime ministership in 2010.

He set about packing the supreme court, shutting down opposition newspapers, had a border built around his country while claiming that ‘refugees’ have flooded into Hungary, decorated almost every bus stop with a poster of a laughing George Soros with the slogan “Don’t let Soros have the last laugh,” and declared the end of “liberal democracy.” And he is continuing to dismantle it every day he is in power.

Edward Serotta is a journalist, photographer and filmmaker specializing in Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe. He is the head of the Vienna-based institute Centropa.