Three Coins and You’re Married

A manuscript sheds light on a 16th-century tale of Jewish love and betrothal

There has been no shortage, over the centuries, of rabbinic literature grappling with questions of Jewish law on marriage and divorce, but the 16th century has been especially generous in this respect. The spectacular story of Tamar bat Joseph Tamari, a Jewish heiress in 16th-century Venice, and the feckless adventurer who betrothed her, captivated the Jewish world in its own day and is still eagerly discussed by historians in our own time. That controversy produced no less than four collections of documents published at the height of the scandal in 1566, one on each side of the issue and two by the fiancé errant himself.

Now a manuscript housed in the Hebraic Section of the Library of Congress offers us another case of a 16th-century betrothal gone wrong, this time from the island of Crete. This is a manuscript of 72 leaves, written in several different hands on thick, high-quality paper and bearing the signatures of several well-known rabbis from the 16th century, among them Moses ibn Alashkar and Elijah ben Elkanah Capsali, the latter also the author of important Hebrew chronicles on Venice and the Ottoman Empire.

![LC Hebr. MS 18 [collection of responsa from circa 1538-1545]. The letter shown here was sent by Moses Alashkar of Jerusalem to Elijah Capsali of Crete [Candia], who had copied it ‘word for word’ on the first page of the manuscript. Note Capsali’s stylized signature at the very bottom of the page. (Hebraic Section, Library of Congress.)](https://tablet-mag-images.b-cdn.net/production/c2294db4ee59a5e9311fd9592252f90158d6ed5a-1024x662.jpg?w=1200&q=70&auto=format&dpr=1)

The manuscript contains a collection of responsa on two different cases, both on the subject of women and their marital status. One case involves a woman whose husband was reported murdered at sea and records various rabbinic opinions on whether the testimony was sufficient to deem the woman free to marry again. The other case involves an unmarried girl and the validity of her betrothal, and this is the case that interests us here.

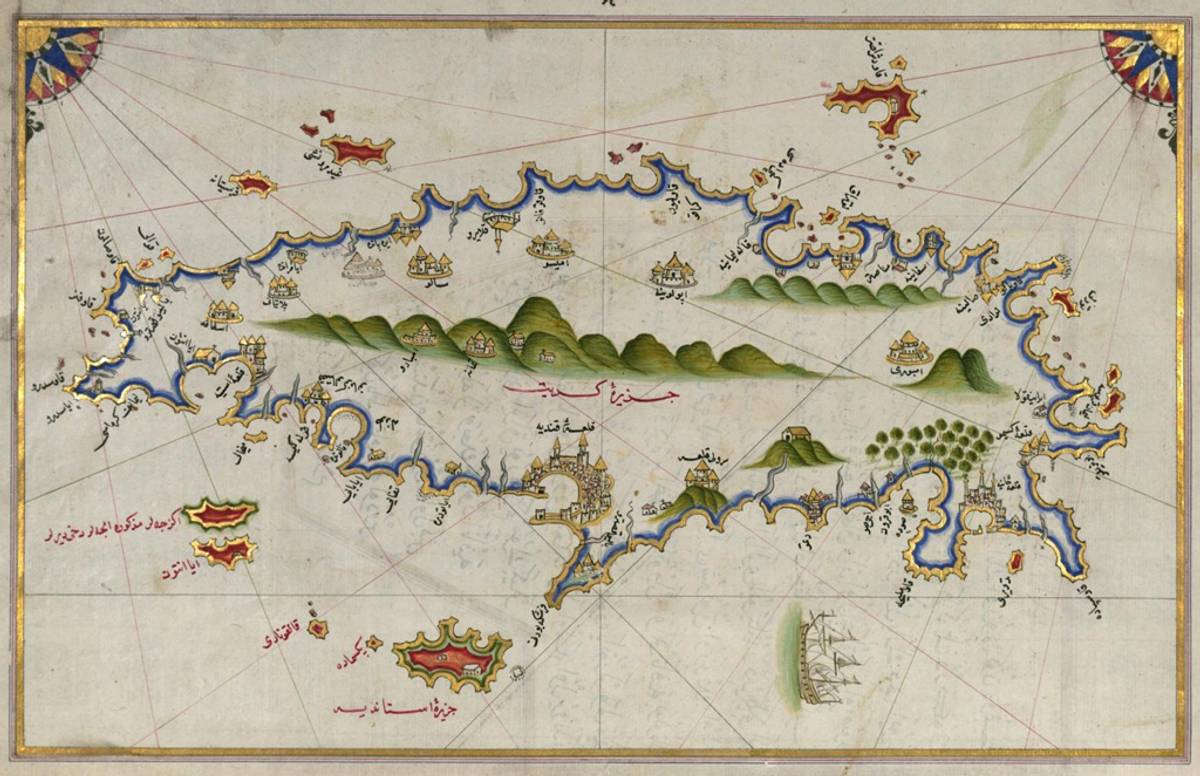

The story begins in Crete, or, as it was known back then, in Candia, a colony under Venetian rule from 1204-1669, in those years when Venice ruled the waves.

The records of the local Jewish community, which extend from 1228 to 1583, attest to a remarkably stable elite with names such as Capsali and Delmedigo weaving in and out of the centuries at regular intervals. The two representatives of these names at the time of our story are Judah Delmedigo and Elijah Capsali, and it is with Kasti, the daughter of this Judah Delmedigo, that our story begins.

Most of the documents contained in this manuscript are known to us from the collected responsa of various 16th-century rabbis in Italy and the Ottoman Empire, among them the renowned Jacob Berab in Safed and David ibn Zimra, chief rabbi of Egypt. But the manuscript does not include all the relevant material and the best place to meet Kasti is in the responsum of Moses ibn Alashkar, an important scholar born in Spain and living in Jerusalem at the time of our story. It is there that we receive the fullest account of the story, including the exact time and place of the incident and the names of the people involved.

Here we learn that the incident in Candia took place toward the end of Passover, 1531, and that in addition to Kasti the story involved one Isaac Bunin of Spain, who was a refugee from Rhodes, and two brothers, Abraham and Isaac Algazu. The story comes in the form of testimony given by the two brothers in the local Jewish court in Candia. The first witness, Isaac Algazu, testified that he and his brother Abraham were playing cards with Isaac Bunin around 9 p.m. one evening during the week of Passover when Kasti bat Judah Delmedigo walked in and took a coin from in front of Isaac Bunin. One of the brothers said to Kasti: “Did you take the coin because you’re thinking of getting married?” At this point in his testimony, Isaac Algazu commented that Kasti was “joshing around,” or perhaps “being mocking” (והיא היתה מהתלת). Isaac Bunin said: “I hereby betroth you.” Kasti fell silent, but then came closer and said to Isaac Bunin: “Give me two more coins and I’ll marry you.” At this, Isaac [Algazu] rebuked Kasti and Isaac Bunin, too, since “he [Isaac Bunin] was all for giving her the coins. But because of the rebuke he did not give them to her.”

Dare we see a reflection of Kasti in this image of a young girl from the western region of Candia [Crete] in the 16th century? Well, probably not. Our Kasti was a city girl, after all, and the basket in this image denotes the peasant. The author of the book notes that many girls in Candia wear shaped bodices in the Venetian style, with long red sleeves. Be this as it may, Kasti would have worn at least one item not pictured here: the yellow badge denoting the Jew. According to law, this badge was round in shape and at least as large as a bread roll: the kind you could buy for four denari.

The testimony of Abraham Algazu is slightly different. According to him, the three men were playing cards in the home of his brother Isaac when “Kasti came and asked each of us for a coin. When she saw we didn’t want to give them to her, she reached out and snatched a coin from in front of Isaac Bunin.” At this, Abraham said to her: “Watch out you don’t end up married.” Isaac Bunin said: “I’d marry you in a minute,” and added, “Take two coins.” But then Isaac Algazu, Abraham’s brother, rebuked Kasti so she didn’t take them. Then she returned the first coin to Isaac Bunin.

Such, then, was the incident that turned into a cause célèbre involving some of the most renowned rabbis of the day and lasting nearly two years. While Kasti’s case is substantially different from the Tamari-Venturi case in Venice, both cases hinge on one basic fact: namely, that according to Jewish law, a betrothal is as binding as marriage. It can only be dissolved if the man grants the woman a writ of divorce; without it, the woman is not at liberty to marry anyone else.

The question was whether or not that incident over cards had rendered Kasti legally betrothed. As noted, the question of betrothal was crucial. If the betrothal was deemed valid, then Kasti would need a writ of divorce in order to marry anyone else. If the betrothal was not valid, then she was free to marry whomever she (or her parents) pleased.

The case found its way to the two most important rabbis on the island, Judah Delmedigo (Kasti’s father) and Elijah Capsali, the latter the chief rabbi of Candia as well as its condestabulo, responsible for representing the Jewish community before the ruling powers. Not too surprisingly, perhaps, the two sages of Candia found themselves at odds over the case, one rabbi upholding the validity of the betrothal and the other negating it. What is surprising, however, is that contrary to what we might expect, it was not Judah Delmedigo who deemed the betrothal invalid. After all, the case involved his own daughter and we might be forgiven for thinking he would be anxious to dismiss the whole incident as quickly as possible.

But just the opposite occurred. It was, in fact, Elijah Capsali who denied the validity of the betrothal, and Judah Delmedigo—the girl’s father—who upheld it. Nor did the incident stop there. Each of the two men then wrote to colleagues in Italy and the Ottoman Empire seeking opinions to bolster his own position and demolish that of his opponent. Judah Delmedigo appealed to colleagues in Constantinople; Elijah Capsali wrote to Rabbi Moses Alashkar in Jerusalem; and before long half a dozen rabbis in cities across Italy and the Ottoman Empire were weighing in on the question. The rabbis discussed points of law touching on the validity of testimony provided by the two brothers and the exact wording of the betrothal spoken by the young man over cards. They quoted the opinions of great rabbis from the past and cited legal precedent. The more they wrote, the more acrimonious the exchanges became until finally, in Padua, the great Rabbi Meir Katzenellenbogen declared that the case was no longer being debated “for the sake of Heaven” but out of “jealousy and rivalry” between the two rabbis of Candia. He refused, moreover, to take sides in the issue lest “the winner then be able to raise his hands and say, ‘Ah ha—I’ve beaten him!’”

![Title page from the first edition of the ‘Collected Responsa by Judah Mintz and Meir [Katzenellenbogen] of Padua.’ Venice: Bragadin, 1553. The letter dealing with this case comes at the beginning of responsum No. 29. (Hebraic Section, Library of Congress.)](https://tablet-mag-images.b-cdn.net/production/010707e9471641e72882ca93496d2efdaacb62a4-500x730.jpg?w=1200&q=70&auto=format&dpr=1)

As mentioned, the manuscript in the Library of Congress does not bring together all of the documents pertinent to the case of Kasti Delmedigo. The above-quoted responsum of Rabbi Katzenellenbogen, for example, is not included there, nor is a responsum penned by one other scholar in the debate, Rabbi Lev ibn Habib, though according to earlier testimony it was at one time included. Most important, the evidence quoted by Moses Alashkar in his collected responsa is not brought in this manuscript collection of documents, where indeed the name of Kasti appears only once (the bottom of Fol. 2), and the other names not at all.

Nevertheless, the manuscript is valuable in bringing together many of the documents, for not only is the sum greater than its parts, but it shines a spotlight on the case and even creates something of a parallel with the more famous Tamari-Venturi case a quarter century later. Of course, the case of Kasti Delmedigo pales in comparison with that case, and has none of the bans, counterbans, or street fights that took place in Venice some 25 years later. Nor—unlike the Tamari-Venturi case, which involved four reigning dukes and the Council of Ten in Venice—did the case of Kasti Delmedigo spill outside of the Jewish community. Nevertheless, one is struck by certain similarities between the two cases above and beyond the fact that both deal with matters of betrothal. For one thing, both cases produced a written body of texts, and while the Tamari-Venturi case produced no less than four separate publications, it is not impossible that the manuscript now in hand was assembled with an eye toward publication as well, most likely by the presses in Venice. For another, both cases illustrate a phenomenon much discussed by historians of the Jewish community in Renaissance Italy, namely, the concerted attempts by the rabbinic establishment to regulate questions of betrothal and marriage (see: Jonathan Ray’s 2013 book After Expulsion: 1492 and the Making of Sephardic Jewry) and brings this case as an example of the laxity deplored by the rabbis in this period. He does not seem to realize, however, that the incident involved Delmedigo’s own daughter. And this of course would have included Candia, as a colony of the Venetian Republic.

But perhaps the most important similarity—indeed, the most poignant similarity—between the two cases is that in each one, the young girl at the heart of the matter seems to have gotten lost in all the legal wrangling. Though we know something about the subsequent life of the young man involved in the Tamari-Venturi case—most notably, that he came under the patronage of Cosimo de’ Medici in Florence—we know nothing about the ultimate fate of the young women involved in either case. Nor can we help but wonder about all that has been left unsaid in the accounts, wordy as they are.

Had Tamar’s heart been engaged to the young man in Venice, or just her hand? And what about Kasti—did she ever live down that night of infamy around the card table? And why in the world was her father so adamant about the validity of her betrothal when his colleague on the island was willing to play it down? Was he simply anxious to show that his daughter was not to be taken lightly? Or to prove, perhaps, that she was not frivolous or flighty? The sources refer to Kasti with varying degrees of disapproval. We have already noted that Isaac Algazu used the word מהתלת to describe Kasti’s behavior, but just how disapproving he was being here it is hard to know; perhaps he only meant “playful,” perhaps he meant “mocking.” But her behavior is characterized as “brazen” (העיזה פניה) in the responsum by Jacob Berab of Safed (No. 17), and here the disapproval registers loud and clear. It seems a high price to pay for a moment of playfulness. Be this as it may, perhaps one day some future scholar will come across the two girls in some as yet undiscovered sources and then be able to tell us the end of their stories. Let us hope they were happy ones.

Ann Brener is an area specialist in the Hebraic section of the Library of Congress.