Jews out West

19th-century Jewish American writers described America’s vastness in lyrical—and liturgical—terms

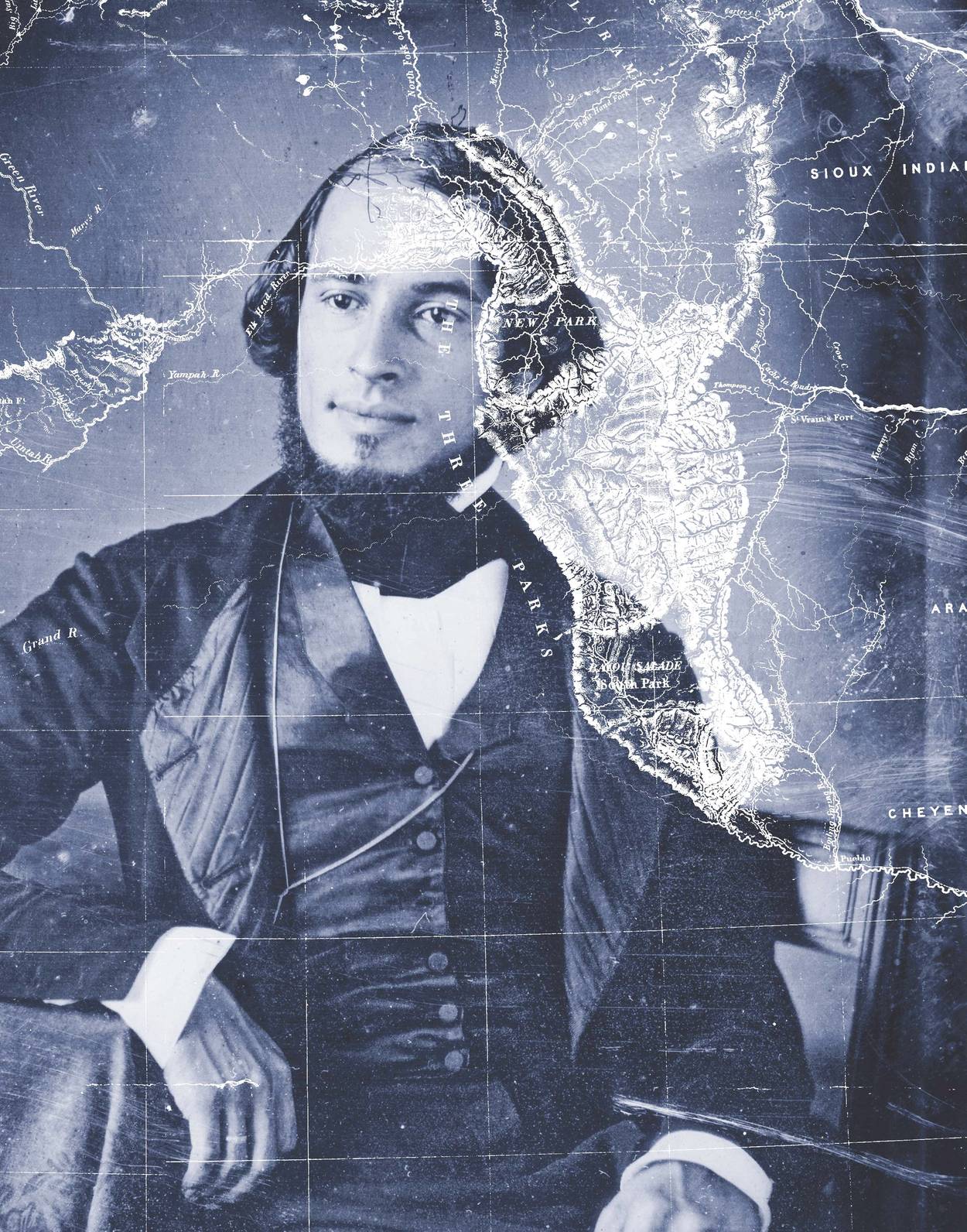

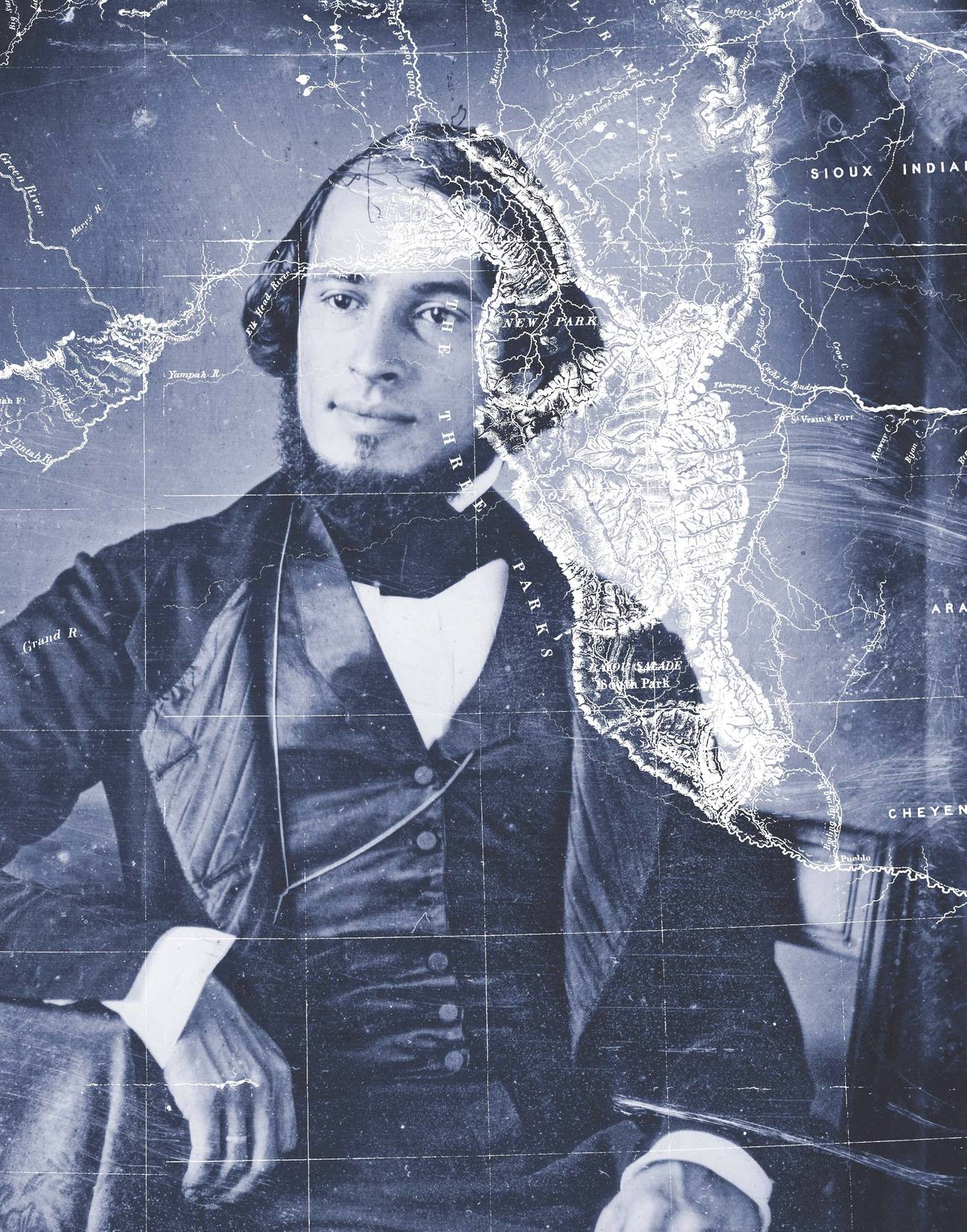

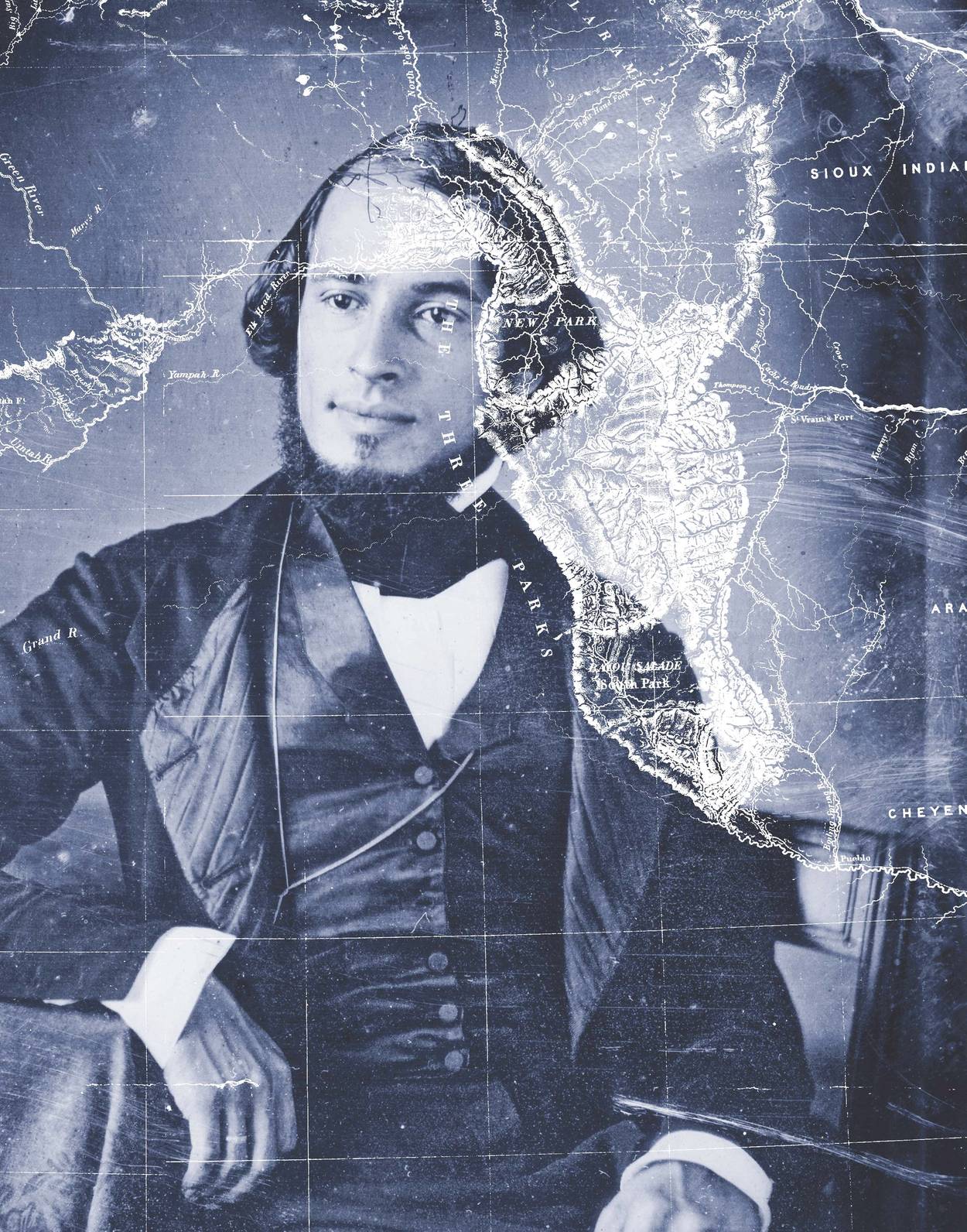

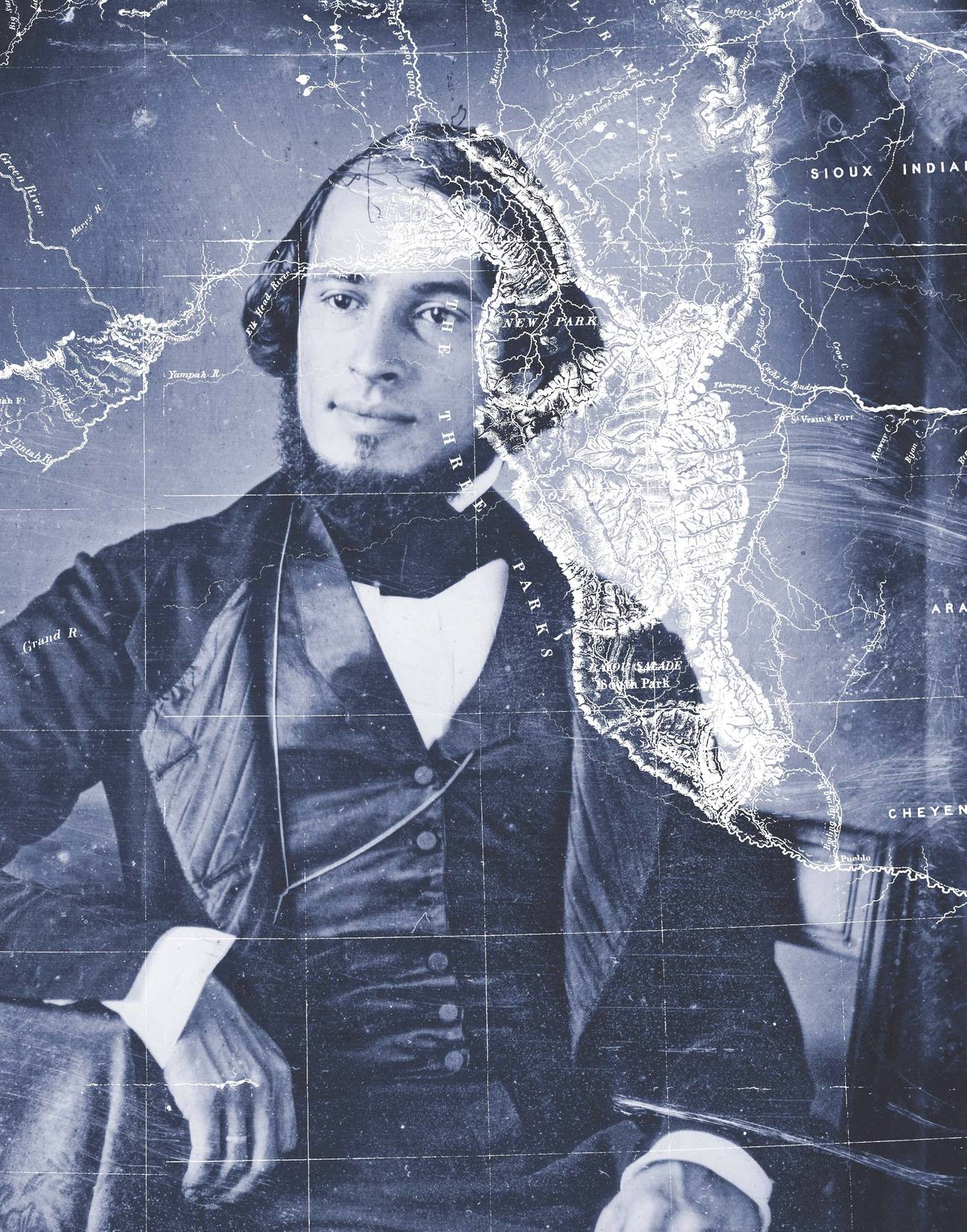

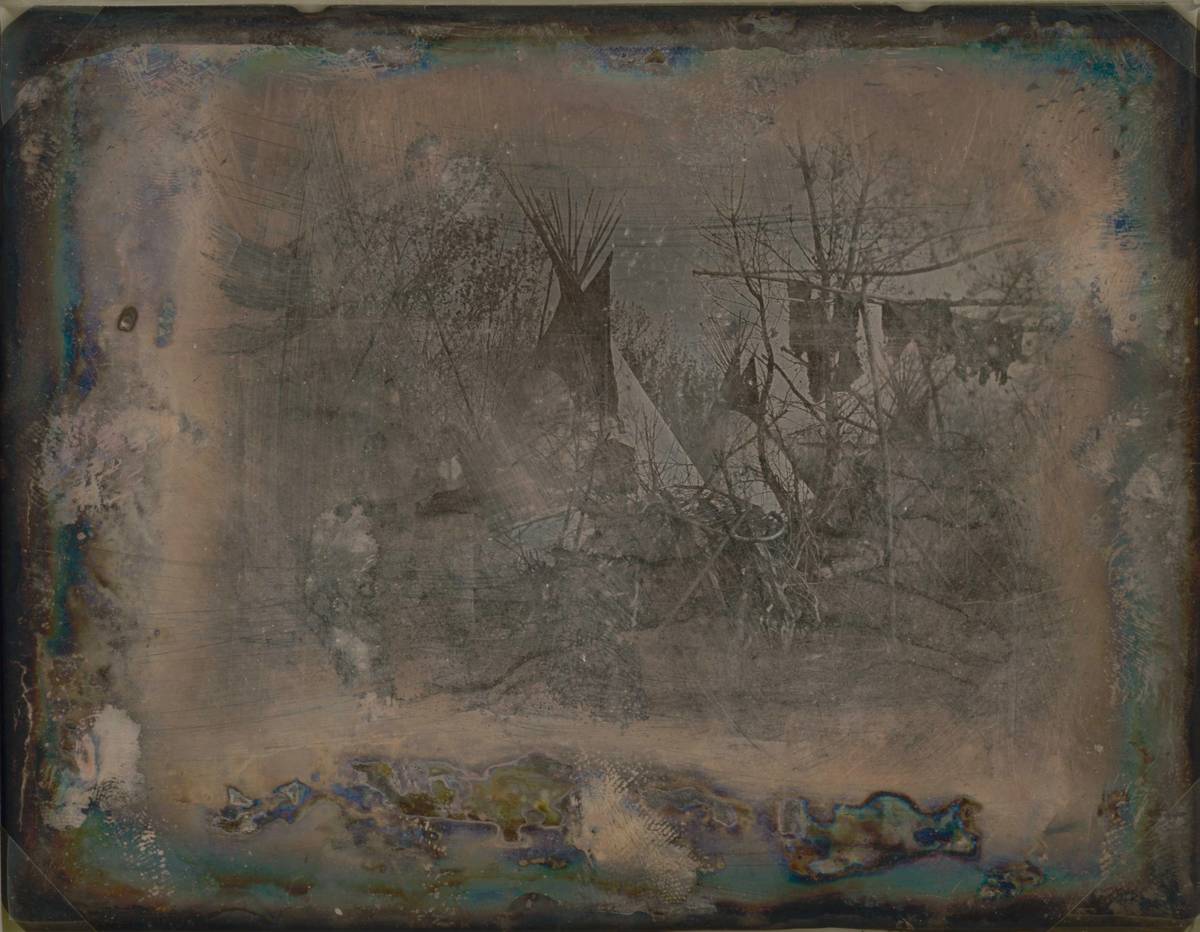

One morning during the late autumn of 1853, a painter and daguerreotypist named Solomon Nunes Carvalho climbed out of a tent on the Kansas prairie to view a spectacular sunrise. The description of the scene that he published three years later was worthy of Ralph Waldo Emerson, but its language also resonated with the Jewish liturgical tradition that the writer had absorbed during the many years he’d spent attending services at the synagogue in his hometown of Charleston, South Carolina. Mounted on his pony and riding away from his campsite, Carvalho looked out to see “floating clouds develop their form against the luminous heavens.” He witnessed “hues of the most brilliant and gorgeous colors as the glorious orb of day commenced his diurnal course and illumined the vault above.” In the “mysterious silence that prevailed”—aside from a handful of members of the expeditionary party with whom he was traveling, there were no humans within hundreds of miles of where he was—this pioneering Jewish American artist and writer gave extended thought to the meaning of all that space. Carvalho’s lyrical exaltation over the American landscape was illustrative of an element within the Jewish American literary tradition that has been understudied and underappreciated. The affinity for place, a dominant motif for American writers extending backward to the colonial-era poetry of Anne Bradstreet and forward into the work of such literary lights as Toni Morrison and Leslie Marmon Silko, is as every bit as Jewish a theme as immigration.

Despite our longstanding tendency to associate Jewish literature in America with feelings of exile, the difficulties of adjustment to a new land, and the idea that Jews came to America from somewhere else, close attention to so much of what we find in it tells a different story. The earliest origins of Jewish American literature lie in the 18th century (actually, if we ignore national boundaries and explore the legacy of Jewish writing in the Caribbean and Latin America, the story begins in the middle decades of the 17th century). When we take its long historical reach into account, as well as the fact that its scope includes such genres as letter-writing, sermons, and personal diaries, we might just as easily argue that Jewish American literature chronicles the experiences of many generations of Jews coming from America. Complications exist, to be sure. Just because Jewish writers may have identified strongly with American landscapes and wanted to consider North America their home doesn’t mean that they haven’t also been wary of being considered outsiders, or, for that matter, neither felt nor expressed misgivings about what it means to “belong” to a nation that was founded by colonializing conquerors. Nonetheless, if the sense of place comes across in literature as an expression of longing, then Jewish writers have participated just as forthrightly in it as other American writers have. No less of a leading light than Philip Roth, describing his first attraction to American literature as a young person, wrote that its “most potent lyrical appeal” to him “lay precisely in the sounding of the country’s most distant places, its spaciousness, [and] in the dialects and the landscapes that were at once so American and so unlike [his] own.”

American geography is as multifarious as its social makeup, and the broad spectrum of types of places in the United States is a direct reflection of its cultural complexity. Readers of Jewish American literature may assume that because its most illustrious and attention-getting practitioners have so often been urbanites, that the only works worth reading are ones that account for urban experiences. That Roth and other denizens of the Jewish American literary firmament such as Anzia Yezierska, Saul Bellow, and Cynthia Ozick produced much memorable and artistically innovative work whose contents explored both the confinements and liberations that defined the Jewish experience of places like New York and Chicago, especially during the first two-thirds of the 20th century, is undeniable. We shouldn’t forget, however, that these and especially other Jewish American writers were often just as eager to explore the worlds that existed beyond the city limits. The title of one of Philip Roth’s most critically acclaimed novels American Pastoral employs the social ascent and physical “escape” of a Newark-born Jewish father to the greener pastures of exurbia and the purchase of his own “hundred acres of America” as a vehicle for exploring the moral decline of America itself during the Vietnam War era. It is as much a study of the pioneering mindset as anything that James Fenimore Cooper or Mark Twain might have written. Its ultimate lesson is that escape is not possible—that America’s pristine rural spaces are only pristine in our longing, delusional imaginations. From the earliest days of European settlement, they were never free of the taint of industrialism, violence, and the “corruptions” that accompany historical experience.

Not that all of this Jewish literature about American places is dark, foreboding, and chastening or, for that matter, hopelessly complicit with acts of conquest. Let’s return briefly to Solomon Nunes Carvalho. His account of frontier life undoubtedly served the cause of Manifest Destiny. (Carvalho served in the officer corps of John C. Fremont’s expedition whose purpose it was to map a railroad route across the Rockies.) Nonetheless, its writing might also be said to have undermined that cause, in part by emphasizing Carvalho’s strong admiration for the Indian scouts and Mexican nationals whose selfless participation had made the journey possible, and in part by challenging the conventions of “heroic” frontier accounts and openly celebrating the occasions when members of the expeditionary party were found rescued and redeemed not by their own heroics but by the kindness of other people (namely, the Utah Mormons who saved his life when he had to bail from the expedition because of the malnutrition and exposure he’d just suffered). Arguably, Carvalho’s most significant contribution to the literature of the American frontier was his lighthearted tendency to self-deprecation. The rollicking enumeration of rookie errors he committed during a buffalo hunt (also on the Kansas prairie) comprises one of the book’s most remarkable passages. When his description of that adventure ended with his having lost his way after having slaughtered a male buffalo whose meat would have been useless to the members of the party, he went on to name a final humiliation: No one, including the group’s head Indian scout whom he so greatly admired, believed any part of the story he tried to tell them around the campfire that night. As the Indian scout explained to him, people who kill buffaloes cut the animals tongues out as proof of their conquest. Since he had no buffalo tongue in his possession, Carvalho might as well have lost his own tongue in that situation.

In a far less self-deprecatory and strangely prophetic mode, Carvalho’s near-contemporary, the Romanian-born Israel Joseph Benjamin, produced a full-length account of the Western frontier in 1862 that also put a Jewish spin on the “meaning” of the Far West. Benjamin, who published his book in Hanover, Germany, authored a text titled Three Years in America, 1859-1862. Alternating from self-important claims of his own significance as an emissary of the European Jewish community to the American frontier to providing exhaustive population counts and surveys of Jewish communities in developing cities like San Francisco and Portland, Benjamin viewed and portrayed himself as a Jewish geographer (inspired and trained by none other than Alexander von Humboldt) whose primary purpose it was to describe the latest efforts of Jews to “plant the seed of civilization in the [virgin] soil” of “the young country beyond the ocean.” Benjamin was nothing if not ambitious, but if we are willing to look past the bluster, self-promotion, and occasional tediousness that we find in his account, we can find in it a fascinating and, indeed, prescient, sensibility. The convergence of his book’s publication with the outbreak of the Civil War gave his account an odd poignancy. Perched at the edge of the Pacific Ocean at a cemetery just outside the San Francisco city limits called “The Mountain of Love,” Benjamin articulated hopes that Americans would see fit to stop building “splendid castles in the air” as dictated by their economic ambitions and, instead, eliminate the scourge of slavery.

If the notion of Jewish frontiersmen strikes us as counterintuitive, the idea that a 20th-century Jewish writer would have been the product of and a booster for small-town American life may seem odder still. This was exactly the case for Edna Ferber, however, who wrote two books during her long and prolific career as a novelist that recounted her growing up years, first in Ottumwa, Iowa, and later in Appleton, Wisconsin. Ferber’s own fairly upbeat treatment of small-town Midwestern life coincided with the popular depictions, most notably dramatized by books like Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (1919) and Sinclair Lewis’ Elmer Gantry (1926), of small-town environments as culturally backward and soul-stealing. For her part, however, and most likely for the very good reason that, as the daughter of at least intermittently well-to-do Jewish shop owners, she had never been trapped in such a town, Ferber was eager to describe her small-town upbringing as, on the whole, a good thing. While her family had been subjected to rough treatment in Ottumwa, she was eager to chalk the townspeople’s anti-Semitism up to a bigotry that she associated not with American life, but with a small-mindedness she associated with “foreign” peoples. Both her semi-autobiographical novel, Fanny Herself (1917), and her 1940 autobiography, A Peculiar Treasure, describe her family’s arrival in Appleton (which took place in 1897) in terms that rival the Israelites’ achievement of the Promised Land. “A lovely little town of sixteen-thousand people; tree-shaded, prosperous, civilized,” Appleton felt like “a cool green oasis after heart-breaking days through parched desert and wind-swept plains.” The town’s mayor was a Jew, as was its most famous native son, Erik Weisz, aka Harry Houdini.

For Edna Ferber, as well as for Solomon Nunes Carvalho and a host of other Jewish American writers, what made America unique wasn’t just the economic and social opportunities it afforded them but the land itself, and the way in which that land, with its openness, its ease of access to other more distant places (including not only cities but also foreign shores) symbolized America’s potential as a modern and thoroughly civilized environment—a place where the Jews might find not only safe haven but the basis for the physical and communal renewal of their ancient culture. The implications have been wide-ranging and, as I’ve hinted above in connection with Roth’s American Pastoral, far from untroubled. The legacy of conquest, as the Western American historian Patricia Nelson Limerick refers to it, has always brought with it a mixed bag of racial erasures, environmental extractions, and economic exploitations. Whether they have sought to celebrate the conquest, critique it, or avoid dealing with it altogether, Jewish American writers have demonstrated their American-ness by attempting to inscribe their presence on the American land.

Michael Hoberman is a Professor of English and American Studies at Fitchburg State University and author of A Hundred Acres of America: The Geography of Jewish American Literary History.