A Double Life

In an excerpt from a new memoir, the revelation of secrets—secret information from a formerly quiet grandmother

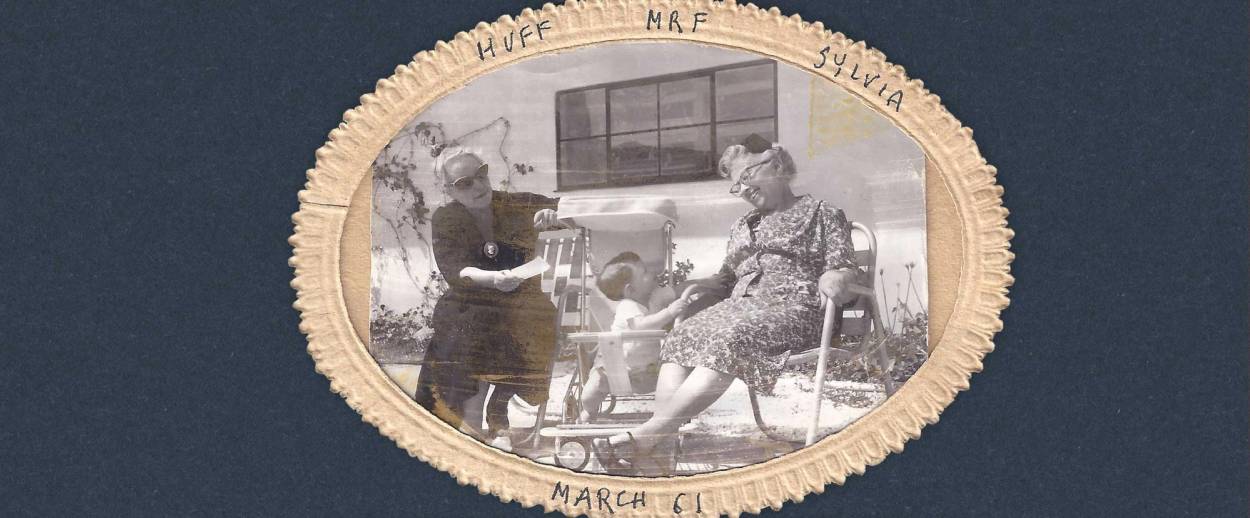

For much of my childhood, my two grandmothers, Harriet Frank Sr., and Sylvia Ravetch, lived unhappily together in an apartment on Ogden Drive in West Hollywood, California, an arrangement I took to be perfectly normal until I grew older and realized that not everyone else’s grandmothers were roommates. Actually: not anyone else’s. Improbable roommates, too, in the case of these two women, who—I understood only later—could not have been more mismatched. Harriet (“Huffy,” in the family) was American-born, Reed- and Berkeley-educated, a writer who had had her own radio program and had worked as a story editor for Louis B. Mayer; she was a powerful personality, outspoken, dominant, and highly charismatic. Sylvia was born in Safed in what was then Palestine, and while she spoke five languages and worked for much of her life as a teacher of Hebrew, her formal education ended abruptly when, at 16, she left her native country. She was quiet, observant, and steady, a resident of the back (thus smaller and inferior) bedroom on Ogden Drive. For years, Sylvia’s volume button was turned down low—until suddenly it wasn’t.

When Huffy died in October 1969, Sylvia moved to the front bedroom on Ogden Drive, and I began to spend time with her at the apartment. A lot of time. On many Fridays after school, Sylvia and I had dinner together at the white pickled table in the dining room. Afterward, we walked in the neighborhood or watched television in the living room or else, especially in winter, we climbed into our beds with our books, each of us grateful, for different reasons, for all that beautiful quiet and space.

On Saturday mornings, Sylvia and I walked to the bus stop—always by the safe route, down Ogden to Sunset, where there was a traffic signal at Fairfax. We waited for the bus to take us to the farmers market at the corner of Fairfax and Third, where my grandmother helped herself to one of the bright green or yellow slatted wooden carts and went from vendor to vendor to do her shopping. I remember how surprised I was when many of them greeted her by name—it was as though I’d discovered she had a secret life. And she had very particular shopping habits that never had managed to announce themselves quite so clearly before. She filled her basket with persimmons, figs, tomatoes, feta, nuts, and greens. Suddenly Sylvia’s Mediterranean origins were written all over the food she bought and prepared for us to eat.

She had friends too. When Huffy was alive, the only neighbor on Ogden anyone spoke to was a woman called Lillian (“Lil”) Lesser, who lived in the corner unit opposite The Apartment. She was a “lady with brains” and therefore suitable acquaintance material for my alpha grandmother. Sylvia, on her own, gaily greeted many of her neighbors in the building and even accepted invitations to tea from the sisters who lived in the mirror-image apartment across the courtyard, two very genteel white-haired widows who baked cookies that shed a dusting of powdered sugar when you bit into them; the decoration of their apartment had previously been pronounced n.g. (= not good) by Huffy and my aunt, who were great adjudicators of style as they were of most everything else, and somehow by implication the women had become n.g. too—but no more.

It was as though Sylvia had changed virtually overnight from someone confined to her tiny back bedroom with its whispering radio to a person who spread her wings, roamed free, and spoke up; spoke up most of all.

For the first time, she told me stories about her childhood in Safed, in what was then Palestine, where in the middle of the 19th century her devout grandparents had immigrated from Galicia and where she had been born. Almost always her stories concerned her family’s terrible poverty: “You cannot imagine.” Only I could imagine, because she helped me to. She told me about her sister Leah (the fifth in line—there were seven sisters in all), who had contracted polio when she was a girl, which I knew because in the few photographs of her that I had ever seen, her left leg, on which she had to wear a cumbersome metal brace, was torn out, by Leah herself. One day when they were small, Sylvia told me, Malka, my great-grandmother, took Leah to the doctor, who advised her to fatten up the stricken child by giving her butter. Butter? They had no money for butter. For seven girls? The very idea of it was unspeakable, and no one spoke of it again. Except that Malka, unable to let the suggestion go, came up with a wily solution. She would buy just enough butter for Leah—she could afford that much—and she would spread it on one side of a slice of bread: the underside. She instructed Leah to eat it discreetly, with the buttered side facing away from the others. And Leah did … until it happened that one of her sisters jostled her and the slice of bread flipped over onto her plate, and a great raucous, jealous, unhappy pandemonium erupted from all the girls—except Sylvia. “I was the only one who realized what my mother was doing,” she said. “I alone understood.”

A year or so after the incident with the butter, Sylvia came home from school one day to find Moses Shapiro, her rabbi father, waiting for her in their two-room stone house. Because of the war, he told her, the help that their community of Hasidic Jews had been receiving from Europe was soon to dry up. Rifka, her older sister, had just been married, but that still left a household full, too full, of hungry girls. The only possible solution he had found was to take the next two in line, meaning Sylvia and Edith, across the ocean to Canada, where a man he knew had arranged for them to work as teachers of Hebrew to well-to-do children in Montreal; how lucky it was, he added, that they had learned both French and Hebrew in school. “You see, Schifra,” he said, opening the envelope to show the tickets for their passage that he had already booked, “you can save us. You and Edith are the future, our future.”

In September 1914, Sylvia and Edith, ages 16 and 14, respectively, left their home, their mother, their sisters, their school, and their friends, and they traveled with their father, who after a journey of 10 days delivered them to a grim boardinghouse in Montreal. They went to work the next day; he left the following week.

To me, all this might as well have taken place in the Middle Ages. “You were 16? It’s not possible.”

“I may have been even younger. I’ve told you, no one wrote down when a girl was born. Girls couldn’t study Torah, so no one cared about girls.”

“Edith was 14!”

“Give or take. About a year older than you are now, anyway.”

A year older than me, living on her own in a boardinghouse with her older sister in a strange city, with no parents, and working at a job. The only paid work I had done at that point in my life was watering my aunt and uncle’s plants when they were out of town.

“You do what you have to do, Michaelah,” she said.

Along with the stories came the revelation of secrets—secret information.

“You have seen—that part of me, the flat part, yes?” she said to me one day. “I know you have.”

I had seen it, yes. A chest as flat as a man’s—flatter. Plainer too, because there were no nipples. Although there were scars, marks. Not knowing what to do with this image, I had pushed it out of my mind until that very moment, when I nodded.

She said, “I am OK. It’s important for you to know that I am OK—now.”

“But what did they do to you—to those pieces of you?”

“They removed them.”

“Why?”

She considered for a moment. “They were diseased. And the disease would have continued to grow if they had left my breasts there.”

“Did it hurt?”

She shook her head. “When you have surgery, you go to sleep, and you don’t feel a thing.”

“And afterward?”

“Afterward you … you get used to it. Anyway, it made it possible for me to live.”

She told me about Merona and Irving’s in-between brother, Herbert. We had come across a box of framed photographs that had belonged to her when she and my grandfather lived in Long Beach; I offered to hang them up for her in her new bedroom. Among them was a photograph of Herbert standing under a huppah with a thin, bright-eyed woman who did not look remotely like his wife.

“Not that one,” Sylvia said, flushing.

“Why not that one?” I asked.

She looked at me assessingly. “I suppose you’re old enough to know.” She placed her palm against her cheek, a familiar gesture. “Herbert was married before. To a friend of your mother’s. She was not … right for him.”

“Not right?”

“It was not easy for him—for any of us,” she said obliquely. “Your cousins have not been told. This is only for you, Michaelah. Farshteyst?”

“Farshtey,” I said, though I didn’t really understand.

I cannot say how exactly or to what extent, but Sylvia recognized that I suffered at school, where I was routinely bullied and beaten-up for a being bookish, artistic; other. When one afternoon she asked about the bruises on my leg, I told her I had been hit with a handball on the playground.

“In two places?” she asked dubiously. I nodded.

“I see,” she said, though the way she said it, while looking at my legs, and then at my face, told me she knew I was lying. But she did not ask anything more. Instead, she wrapped ice cubes in a dish towel and daubed them against my legs.

The ice was comforting, but Sylvia’s deeper balm was the way she embraced me so completely and unquestioningly. It helped that her home, being removed from our neighborhood, was so far beyond the reach of the bullies that it might as well have belonged to a different city entirely. I didn’t know any kids; I wasn’t marked. I was free to be myself, much as, in the aftermath of Huffy’s death, Sylvia was free to be herself.

In this safe house I was free to be myself in the company of a woman who asked nothing in return but my company. She had no agenda, no ideas to impose, no particular philosophy to advance, no competition to win, no stories to control, nothing on offer, really, but love.

Little did we know what, or who, threatened our safe house on Ogden Drive. But we were to find out soon.

***

Excerpted from The Mighty Franks: A Memoir, by Michael Frank. Copyright © Michael Frank, 2017. Reprinted with permission.

Michael Frank is also the author of a memoir, The Mighty Franks, and What Is Missing, a novel.