A Milkman in Winter

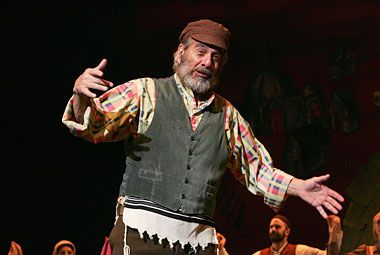

After 42 years, ‘Fiddler on the Roof’ star Topol is still stuck in Anatevka

Fiddler on the Roof, the Bock-Harnick musical based on Sholom Aleichem’s stories of life in the Russian shtetl, opened on Broadway in September, 1964, with Zero Mostel in the central role of Tevye the Milkman. But the Israeli actor Chaim Topol—usually billed mononymically, as Topol—has become perhaps even more associated with the character. Topol, then 31 years old, starred in Fiddler’s 1967 West End debut; he starred in Norman Jewison’s 1971 film version; and he’s played the character around the world—by his account, more than 2,500 times. (That puts him well ahead of onetime record-holder Paul Lipson, Mostel’s original understudy, who, according to his 1996 New York Times obit had played the role 2,000 times.) Now 73, he’s yeidel-deideling his way up the West Coast of the United States, part of a two-year Fiddler tour that’s being billed as Topol’s farewell. He spoke to Tablet Magazine from the rooftop restaurant at the Peninsula Hotel in Beverly Hills, where he stayed during a recent, sold-out run at L.A.’s Pantages Theater, about Tevye, Israel, and whether this is really his last hurrah.

You’ve been doing this role for more than 40 years. What has Topol learned from Tevye?

When I first played Tevye, Israelis had kind of detached ourselves from living in the Diaspora, and all the problems that Jews had in the Diaspora, pogroms and so on. We weren’t able to digest the huge catastrophe that happened, the six million killed. People who came from there, the survivors, didn’t talk. We, in Israel, didn’t understand anti-Semitism—what it means when someone doesn’t like you because you are Jewish. Although my father and mother were the only two survivors in their families, because they arrived to Israel from Poland in the early ’30s; probably my great-grandfather was a Tevye.

I’ve always felt like the end of the show—we’ll have to go wait for the Messiah someplace else—makes a pretty clear argument for the existence of Israel.

For me, it’s an axiom. I grew up on that idea. I was there when Jabotinsky and other people were saying that if you want to live the Diaspora, you won’t live. It’s funny, this morning, I hummed to myself a song that my father used to sing. “Sing the song of flowing land…,” a kibbutznik song, and I thought, who would write a song like that today? But for people who came to Israel then, it was such a sensation for them. I thought, what sort of happiness that they made of hard work. And there they were, singing a song to the hard work.

But, then, also, you have that line as the Jews are being evicted from Anatevka, “this corner of the world has always been our home.” It’s a point that could be made about Palestinians in the territories today.

It’s not an equivalent, because we don’t want them out, they want us out. And it was certainly our corner of the world before theirs.

But Israel is the one in control now, issuing edicts.

The stronger force by necessity, because otherwise they would do to us what the Germans did to the Jews, and they are not declaring it, they are hiding it quietly. But that’s what they say, that’s what the Hamas say, that’s what the Iranians say, that’s what Arabs say. We’d better be strong.

Have there been any memorably unsuccessful performances? I imagine it doesn’t translate as well to some—

You’re wrong. It translates to Japanese very, very well. It translates to—

I’ve seen it in New York, and in L.A., surrounded by the descendents of Eastern European Jews. You’d think that’s a very different experience from Tokyo.

I was in Australia three years ago. I was in places where maybe in the entire area there are probably a thousand Jews. It was packed by Chinese, by Indians, by Koreans, by Vietnamese, by Yugoslavs, by Turks. And all identify with it. It’s not that they say, “Ah, this is how the Jews lived.” They say, “This is how my family lived.” In Australia, 90 percent are immigrants. So when you sing, in “Anatevka,” “Soon I’ll be a stranger in a strange new place, looking for a familiar face,” they know exactly the feeling. They cry during “Anatevka” no less than any Jewish family. Everyone, they cry in exactly the same places, and they laugh exactly in the same places.

The audience at the Pantages gave you I think the loudest, most excited entrance applause I’ve ever heard.

I think it’s excitement to see Tevye. Well, probably Tevye portrayed by Topol. But Tevye. You should blame the film for it, because the film was seen by a billion people.

Is there any part of you that’s frustrated that you’ve been so associated with this role for so long years?

Not at all. I’m very thankful and very grateful to my luck to be associated with a role like that. In the whole world, there are probably four or five guys who are associated with a role, and I’m sure they’re very proud of it. I mean, it’s Yul Brynner with the king, Rex Harrison with My Fair Lady, Tony Quinn with Zorba, the James Bonds…

Any truth to the rumor that on your tax return you list your occupation not as “actor” but simply as “Tevye”?

Really? I should try it.

Why are you saying farewell, then?

I don’t think farewell. I think it’s a good way for the producers to promote it.

So you’d consider doing it again.

If they’ll ask me, I’ll do it again.

Jesse Oxfeld, a former executive editor and publisher of Tablet Magazine, is a freelance theater critic. He was The New York Observer’s theater critic from 2009 to 2014.