A Poet for Our New Gilded Age

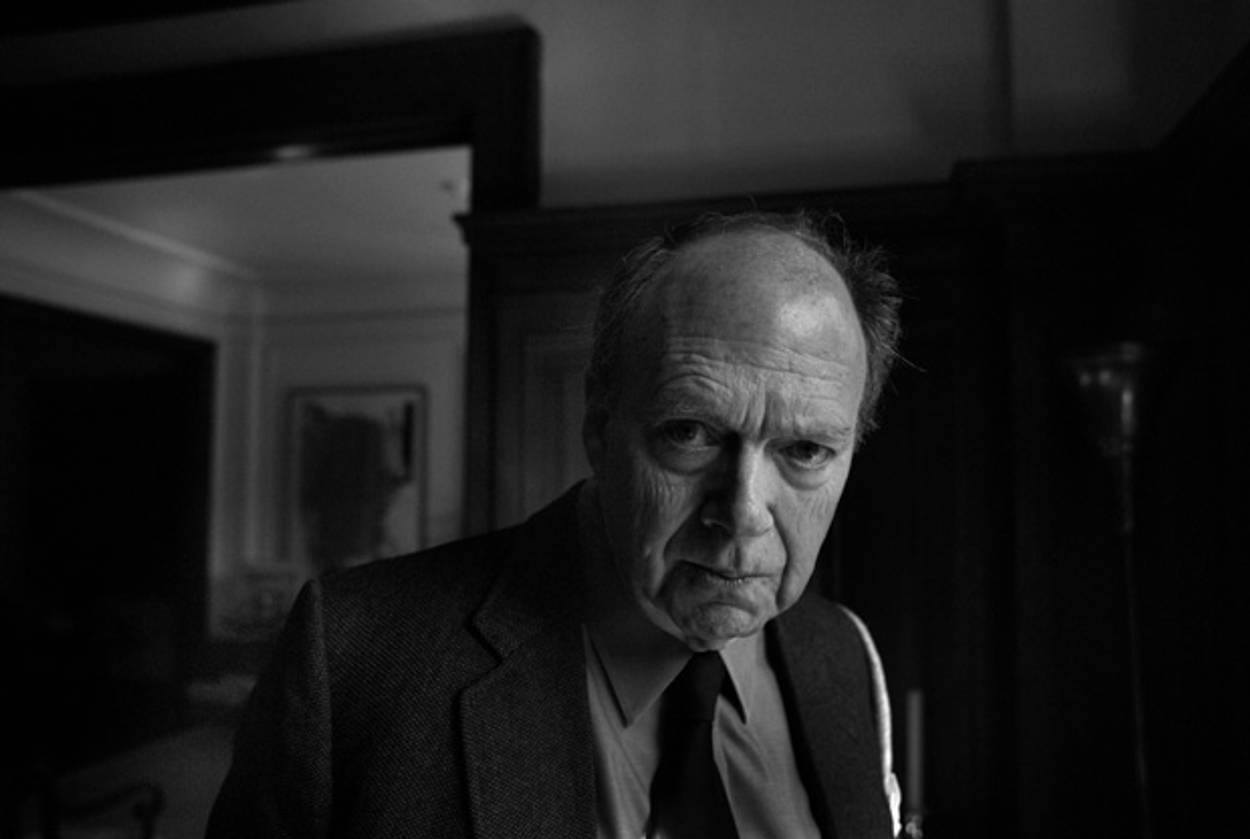

The latest collection from the great Jewish poet Frederick Seidel expresses intimate revulsion at human feats

When Frederick Seidel’s career-defining Poems: 1959-2009 was published a few years ago, the poet received a burst of the kind of publicity he spent most of his life avoiding. For the first time, there were photos of Seidel in magazines and profiles describing his life—his St. Louis childhood, his apartment on the Upper West Side, his love of deluxe Italian motorcycles. No one could argue that Seidel didn’t deserve the attention: He has long been one of the best and most exciting American poets and yet had been almost totally ignored by the poetry world, receiving none of the major prizes and omitted from the big anthologies.

At the same time, however, it was a kind of shame that the real, bodily Seidel stepped out of the shadows of his work. A large part of the transgressive power of his poems comes from the indeterminacy of the man who speaks in them. As he wrote in “Milan,” in his 1998 volume Going Fast:

Combine a far-seeing industrialist.

With an Islamic fundamentalist.

With an Italian premier who doesn’t take bribes.

With a pharmaceuticals CEO who loves to spread disease.

Put them on a 916.

And you get Fred Seidel.

The impossibility of bringing this sinister composite into focus is the whole point of the poem. In all his work, Seidel remains a larger than life figure, full of vice, menace, and power, and capable of uttering the most shocking thoughts. He writes with the same risky power as John Berryman and Sylvia Plath in their confessional poems. Berryman, however, wrote of his inner torments by inventing a surrogate named Henry, while Plath incarnated herself in a series of voracious, quasi-mythical speakers. Seidel, by writing under his own name yet predicating such impossible and scandalous things of himself, raises the stakes of confessional poetry to a new level:

I sit at my regular table in a restaurant I favor,

Napkin tucked into my collar, eating dirt and a stone,

Stooped over in a La Tache stupor. I know it’s disgusting but I savor

My African-American antipode with her hand out outside the window, my clone,

Begging just outside on the sidewalk. I’ll buy her and take her home. We’ll eat dirt.

We’ll grovel in the grass and bat our eyes and flirt.

That is from a poem titled “My Poetry,” and it has many of the hallmarks of Seidel’s late work: the ugly surrealism, the jaunty, singsong rhymes, and the disgust with wealth and power. For while Seidel’s poems are usually set in the world of privilege—Harvard, the Carlyle Hotel, and Sagaponack are recurring locations—he writes about high society in a spirit of intimate revulsion. He is always slightly outside the WASP aristocracy he leers at—a position he owes in part to being a poet, and in part to being a Jew, of a generation when Jews were ill at ease in such settings. Seidel’s first collection, published in 1963, was titled Final Solutions, and his vision of a corrupt and endangered human species is deeply informed by the Holocaust, which took place during his safe American childhood:

I don’t want to remember the Holocaust.

I’m thick of remembering the Holocaust.

To the best of my ability, I wasn’t there anyway.

And then I woke.

…

I wasn’t there anyway.

I don’t believe in anything.

I was somewhere else

Screaming beneath an avalanche.

Seidel is now 76 years old, yet his new collection, Nice Weather, out this week from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, betrays no falling off in daring or up-to-the-moment engagement. As always, familiar headlines appear in Seidel’s poems in weirdly refracted forms, as in “Lisbon,” which treats of President Obama’s election and inauguration:

I love the future I won’t live to see. I don’t know why.

And don’t even know if it’s true.

Maybe I’ve already lived to see the future.

My multiple personalities climb to altitude on a single pair of wings.

Luxury Man rises to the top and Evening Man brings

To the podium the first African-American president to sing fado,

Chicago fado dado didi dado. Obrigado.

The trailing off into nonsense is not new in Seidel’s work, though this is not the most effective example of the technique. What is new is the sense, pervasive in Nice Weather, that he is coming to the end of his life and, what may be worse, of his potency. Like the late work of Robert Lowell, Nice Weather confronts these losses with a combination of nostalgic resignation and fierce defiance:

I face a yawning lion shaving in my mirror in the morning, roaring,

And there’s my grandchild standing in the doorway, adoring—

Many teeth to brush, a beard to shave!

OK, it’s not solace, but it’s not nothing, still to be able to roar, to rave

With vim and vigor about the loss of vim and vigor.

It’s sort of like a finger on the trigger

Is facing me in the morning mirror, and starts to snigger.

Many elements of Nice Weather, in fact, can be traced to Lowell, in a way that makes the book feel valedictory—a salute to the poet who has influenced Seidel more than any other. A poem called “Midterm Election Results, 2010” begins “My old buddy, my body!”, calling out to Lowell’s “The Old Flame,” which starts, “My old flame, my wife!” Lowell’s last book, Day by Day, is full of leisurely reminiscences of his schooldays and his Harvard friendships; so is Nice Weather, which includes several elegies for old classmates and a suite about Harvard titled “School Days” (“Updike is dead./ I remember his big nose at Harvard/ When he was a kid.”)

The most famous line in Lowell’s late work is from his poem “Epilogue”: “Why not say what happened?” But here Seidel can’t follow him. For Seidel, saying what happened has always been a game, in which the truth is distorted into a hundred teasing shapes. Is “Do Not Resuscitate,” for instance, a description of a nightmare, an elegy for a dead spouse, a poem of self-reproach, or all three at once?

The mummy in the case is coming back to life.

It sits up slowly. I can’t bear it.

The guard pays no attention. He knows it is my wife.

Her heart sits blinking on her shoulder like a parrot.

…

I loved my wife to bits. I loved her tits.

Her bandaged mummy mouth had nothing else to give.

“All the poems he wrote, and so few dedications,” the poem ends—an eloquent statement of regret for the brutal aloofness of his poetry. And in Nice Weather, Seidel comes across as more sentimental, more clinging to life and love, than ever before. (“Jews grab/ The thing they love unless it’s ham,/ And hold it tightly to them lest it die,” he writes in one poem, savoring the bad joke.) Several poems seem to describe a love affair with a much younger woman, as in “Arnaut Daniel”:

Age is a factor.

A Caucasian male nine hundred years old

Is singing to an unattainable lady, fair beyond compare,

Far above his pay grade, in front of Barzini’s on Broadway

Barzini’s is a specialty grocer on 91st and Broadway—another example of the local accuracies that are mixed in with Seidel’s outlandish fantasies and help to give them their power.

The most moving poems in Nice Weather, however, are those in which Seidel reflects on his artistic accomplishment and how it weighs in the balance with death. At times he is cynical and dismissive, as in “They’re There,” an elegy for the critic Frank Kermode: “Don’t try to tell Frank that his charming work won’t die./ The dead don’t give a shit/ About their work once they die,” he says flatly. In other poems, he seems to regret the way the persona he has constructed in his work will replace him in the world after he disappears:

My fourteen books of poems

Tie a tin can to my tail.

You hear me fleeing myself.

I won’t get away.

But it is not for a writer like Seidel to ask for the reader’s pity. He remains, even now, a poet of wonderful fearlessness and daring, and he deserves to be remembered as the transgressive adventurer he is: “A Jew found frozen on the mountain at the howling summit,/ Immortally preserved singing to the dying planet from it.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.