A Slap in the Face

Beate and Serge Klarsfeld’s moving memoirs trace the evolution of a new idea: that Germans were responsible for the Nazi past. Can today’s Europe learn from their moral courage?

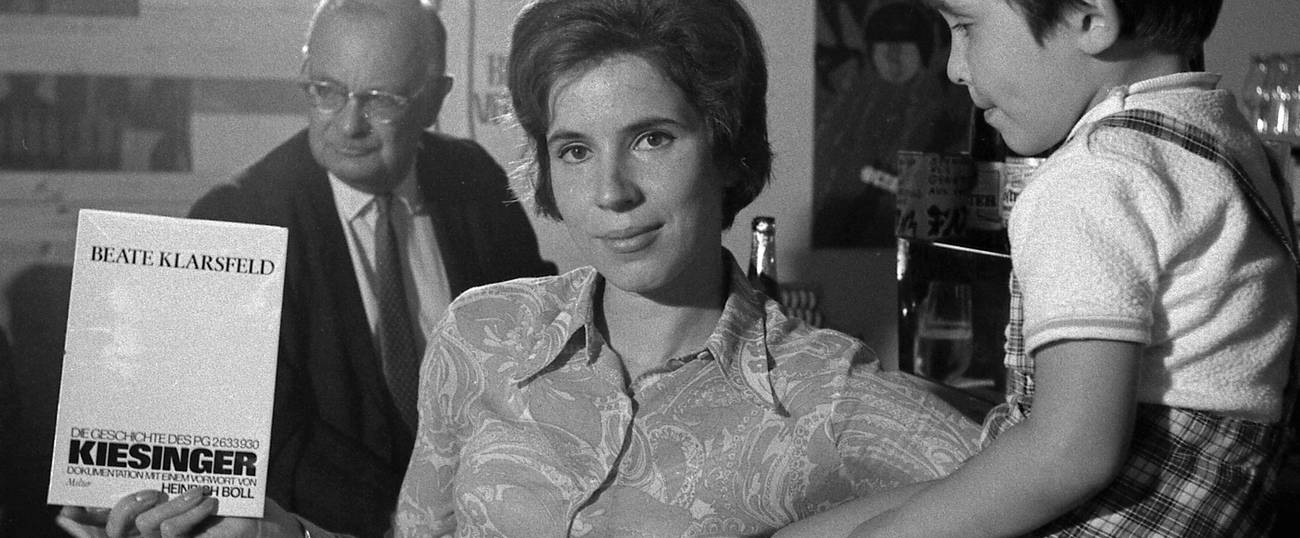

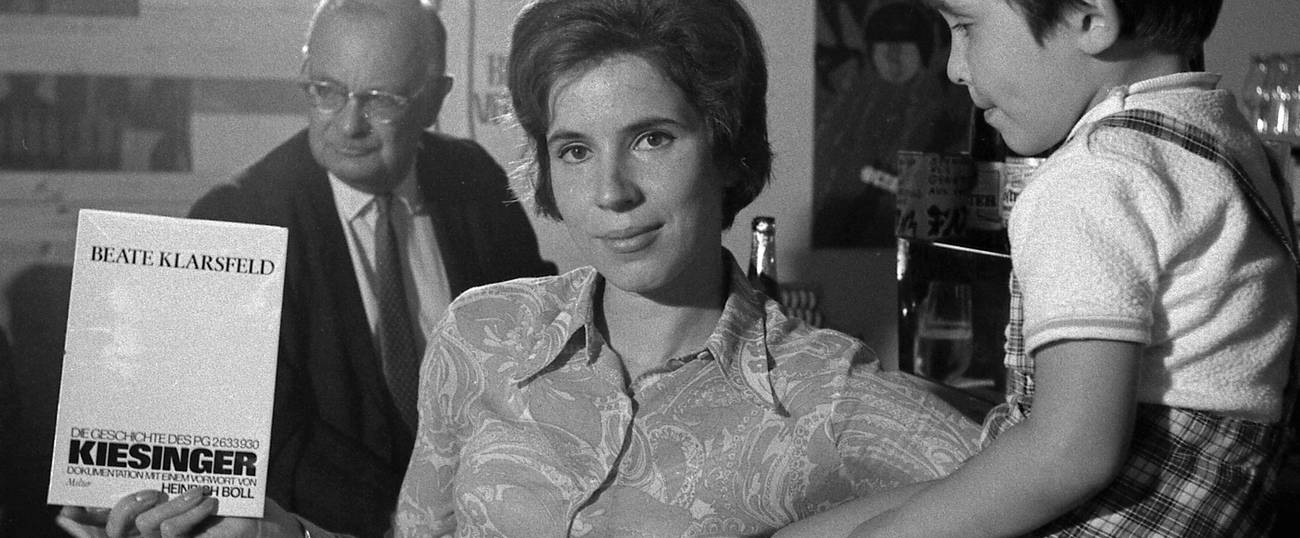

Beate Klarsfeld had been saying for weeks that she would slap the chancellor. Twenty-five years earlier Kurt Georg Kiesinger had been Hitler’s assistant director of foreign propaganda in France. Now he was Germany’s head of state, and this ought to be a scandal, Klarsfeld thought. On Nov. 7, 1968, the 29-year-old Klarsfeld rushed across the stage during a meeting of Kiesinger’s Christian Democratic party and struck the surprised chancellor across the face. “Ohrfeige für den Kanzler!” (“A slap for the chancellor!”) the newspapers excitedly proclaimed.

It was the “slap heard ’round the world,” the Süddeutsche Zeitung announced, and perhaps the most convincing bit of political theater ever. Heinrich Böll, the novelist and future Nobel Prize winner, sent flowers to Klarsfeld, writing in the newspaper Die Zeit that Kiesinger was one of “those bourgeois Nazis who did not get their hands dirty, and who have continued, since 1945, to stroll shamelessly through German public life.” Böll added that when he and his fellow writer Günter Grass condemned Kiesinger they merely “play[ed] the ludicrous role of ‘the nation’s conscience,’ to be proudly displayed in other countries.” Böll hoped that Klarsfeld, by contrast, might actually change the nation’s mind about whether an ex-Nazi should be the head of their government.

And so she did. Before long, Kiesinger’s speeches were being greeted by chants of “Kiesinger Nazi.” In September 1969 his party lost the election to the rival Social Democrats. The new chancellor was Willy Brandt, who had left Germany when Hitler took power. The next year Brandt would fall to his knees before the monument to the Warsaw ghetto fighters. A new era in German history had begun, in which a reckoning with the Nazi past was not only permitted but mandatory. Beate Klarsfeld was more responsible than anyone for this sea change in German public life. She received a four-month suspended sentence for her attack on the chancellor, a tacit recognition that her slap had some moral force behind it.

For Beate and her husband, Serge, hitting Kiesinger was the beginning of a five-decades-long career as political activists, which they recount in their new memoir, Hunting the Truth. Beate alternates chapters with Serge so that the book becomes a heartfelt dialogue between the two. The Klarsfelds are Nazi hunters, committed to bringing German and French war criminals to justice. They have also campaigned against anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, and to stop massacres elsewhere in the world, from Beirut to Sarajevo. In 2015 Beate traveled to Burundi to protest ethnic cleansing in the African nation. Two years later they battled against Marine le Pen’s campaign for the French presidency. In the last few years, they have been alarmed by the increasing anti-Semitism in France, where, Beate writes, “Hatred of Israel has become so commonplace that it has led to hatred of Jews becoming commonplace, too.”

***

Beate was born Beate-Auguste Künzel to a non-Jewish German family in Berlin. Her father was a soldier on the eastern front who luckily caught pneumonia in the winter of 1941, so he returned to Germany and became an army accountant. In 1943, the family spent a few luxurious months in Lodz with Beate’s godfather, a high-ranking Nazi, never mentioning the fact that the Jews of Poland were being annihilated all around them. After Hitler’s fall the Künzels lived mostly on potatoes and lard, in a one-room apartment they shared with another woman.

Beate’s parents learned nothing from the “epochal events they sleepwalked through,” Beate writes. “They weren’t Nazis,” she adds, “but they had voted for Hitler like everyone else, and they did not feel any responsibility for what had occurred under Nazism.” Gossiping with the neighbors, her mother lamented the loss of favorite household objects during the war but never had a word of compassion for what other peoples had suffered, least of all the Russians.

The 21-year-old Beate preferred East to West Berlin, and took solitary trips there on Sundays: “It was so dark and poor, but I was drawn by its unknown past.” Restless and alienated, she realized that she wanted to leave Germany. She went to Paris as an au pair, and it was there, at a Metro station, that she met Serge Klarsfeld, a handsome young man in a suit who asked for her phone number.

Serge, she soon learned, was a Jew whose father had been murdered at Auschwitz. In 1943, when the Klarsfelds were hiding in a borrowed apartment in Nice, the Gestapo knocked on the door, and Serge’s father answered. Eight-year-old Serge squeezed into an armoire along with his mother and sister. The Gestapo searched the apartment, and opened the armoire: “Seventy years later, I can still hear the sound of the clothes sliding along the rod,” Serge says—but the Klarsfelds were concealed behind a partition. The Germans left with Serge’s father, persuaded by his story that he had sent his family to the countryside. Years later Serge learned that his father was sent to the coal mine at Fürstengrube, a certain death sentence, because he had struck a Kapo in Auschwitz. Had he not defied the Kapo, Serge’s father might have survived the war. Rather than defiance, Serge chose a cool and determined method, pursuing the Nazi murderers through the courts.

Serge plunged Beate into a new existence, writing to her, “You must poeticize your life, Beate, re-create it, live it consciously. … A bit of courage, cheerfulness, energy, connection to humanity.” He talked to her about the Scholl family, who were executed for distributing anti-Hitler leaflets in Munich in 1943. Beate suddenly understood “that it was not only difficult but thrilling to be German after Nazism.” Her fight against Kiesinger embodied a new idea, that Germans were responsible for the Nazi past. They thought Nazism was something that had happened to them, but instead, it was something they had done. Beate told Germans that owning the Nazi crimes was not a mere burden but rather, to use her word, thrilling, an awakening to the truth.

After Kiesinger, Beate rapidly widened her campaign against anti-Semitism to include the Eastern Bloc. Through her connections in East Germany, Beate snuck into Warsaw in August 1970, chained herself to a tree in the town square, and handed out leaflets denouncing the Polish government’s anti-Semitic campaign, “the elimination of the Jews that is still going on in Poland.” The next year, she went to Czechoslovakia to protest the Czech Communist Party’s campaign against “Zionist elements.” Even riskier, she condemned the persecution of Soviet Jews. Beate’s family feared for her life: Two years earlier, the Czech Secret Service had drowned a member of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. Poland had expelled her instantly, but in Prague, she served a short stint in jail. In the end, she was sent across the Austrian border and warned not to return.

A lawyer, Serge quit his job at Credit Lyonnais in 1970 so he could work on the dossiers of Nazi war criminals living in Germany even though French courts had condemned them in absentia. Chief among these men was Kurt Lischka, the head of the Gestapo’s Jewish Affairs Department in France. Lischka had been sentenced to life imprisonment by a French court, but he lived openly in Cologne, a wealthy industrialist whose name was in the phone book. The Klarsfelds began stalking Lischka: They filmed him outside his house and gave the footage to television news. Lischka could not be tried in Germany because the Bundestag was dragging its feet on the legal agreement that would permit such trials. So the Klarsfelds tried, and failed, to abduct him and carry him across the border to France. The Franco-German legal agreement, now known as the Lex Klarsfeld, was finally ratified in February 1975, so that Nazis with the blood of French Jews on their hands could, at last, be put on trial.

‘You must poeticize your life, Beate, re-create it, live it consciously. … A bit of courage, cheerfulness, energy, connection to humanity.’

In Cologne in 1974 Beate, waiting to be tried for her actions against Lischka, shared a jail cell with Christel Guillaume, wife of the East German mole Günter Guillaume, who had infiltrated Brandt’s government. The same jail housed the Baader Meinhof women, who trashed their cells in protest, while Klarsfeld and Guillaume kept theirs spotless. Beate received, again, a suspended sentence. Golda Meir announced that “to Israel and the Jewish people Beate Klarsfeld is a ‘Woman of Valor’—a title that has no peer in Jewish tradition.” The Klarsfelds became frequent visitors to Israel, sometimes guests of Teddy Kollek at kibbutz Dalia.

In preparation for the trial of Lischka and two other top Nazis, Serge collected 11 volumes of documents on the Final Solution in France. Lischka had still not been arrested, so the Klarsfelds enlisted some students as well as a rabbi and Auschwitz survivor, Daniel Farhi, to smash the windows of Lischka’s office. The trial finally began in 1979, and when it was over Lischka got 10 years.

The Klarsfelds’ most famous victory was the extradition of Klaus Barbie from Bolivia to Germany to stand trial. Barbie was the “butcher of Lyon,” who as local head of the Gestapo tortured and killed many prisoners by breaking their bones, setting dogs on them, and other barbaric methods. Barbie also led the raid on the orphanage at Izieu, where in 1944, 44 Jewish children were sent to their deaths; Serge Klarsfeld later wrote a book about the young victims, The Children of Izieu. Serge’s exhaustive research revealed that Barbie was living as Klaus Altmann in La Paz, Bolivia. In fact, Barbie’s existence was no secret to the West’s spy networks, which cared nothing about bringing him to justice. The U.S. Army’s Counterintelligence Corps had helped Barbie escape to Bolivia after the war, and German intelligence employed him as an agent in the 1960s.

After years of hard work by the Klarsfelds, Barbie was extradited to France in 1983, and four years later received life imprisonment for crimes against humanity. Meanwhile, in 1986, Farrah Fawcett played Beate in Nazi Hunter, a made-for-TV movie.

The Klarsfelds fought against the French tendency to make excuses for the Vichy regime. Vichy was often thought of as a necessary compromise with Nazism: President François Mitterand defended Marshal Pétain, even laying a wreath on Pétain’s grave each year. Serge Klarsfeld made such a forgiving attitude toward Vichy’s leader impossible. In 2010 he proved that Pétain was behind Vichy’s anti-Semitic decree of 1940. It has long been known that Pierre Laval, Vichy’s second in command, rounded up Jewish children on his own initiative, rather than being forced by the Nazis. But only recently did a French president, François Hollande, declare that the Vél d’Hiv deportation of Jews to their deaths was “a crime committed in France, by France.” Serge Klarsfeld has written a powerful documentary history, French Children of the Holocaust: A Memorial, filled with heartbreaking glimpses into the lives that were cut short by the fascist police of Vichy.

The Klarsfelds’ story has some lessons for us at a time when political activism seems adrift, unsure about its targets and tactics. Their methods, assiduous research combined with illegal, highly symbolic actions, were perfectly chosen, and their goals were clear. They argued that Germans should feel guilty for remaining silent about the Nazi past and they provided a clear pathway to reparation: bringing Nazi war criminals to trial. The Klarsfelds retained their moral compass: Unlike many German leftists, they were disgusted by the Soviet Union’s plan to eliminate the state of Israel by arming its Arab enemies. After its leader Rudi Dutschke was shot in 1968, the German left fell prey to terrorists like the Baader Meinhof gang, who insisted that capitalism and fascism were synonymous. Their bombings, hijackings and other acts of terror, including the kidnapping and murder of businessman and former SS lieutenant Hanns-Martin Schleyer, turned Germany against them. This bloody vision culminated in the 1976 Entebbe hijacking, where Palestinian and German hijackers separated Jewish and non-Jewish passengers and held the Jews hostage. In a burst of high irony, the anti-fascist Reds behaved exactly like Nazis.

Beate Klarsfeld’s lawyer when she went to court for slapping Kiesinger was Horst Mahler, one of the founders of the Red Army Faction. Mahler is now a Holocaust denier and right-wing anti-Semite, a perfectly logical trajectory, since the rootless conspiracy theories of the hard left have much in common with right-wing nationalism. The Klarsfelds, by contrast, have been honored with Israeli citizenship, along with their son, Arno, who has carried on the couples’ work by prosecuting Maurice Papon for helping to round up the Jews of Bordeaux. Beate Klarsfeld has been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize and for the German presidency.

Together, the Klarsfelds testify to the stark choice that confronts Europe now. There is blind nationalism and anti-Semitism of the left and the right, but also a willingness to learn from the past and to stand for decency. What’s missing is a catalyzing action like Beate Klarsfeld’s in 1968. Sometimes moral awareness requires a slap in the face, but whose?

***

Read David Mikics’s Tablet reviews of political and historical nonfiction here.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.