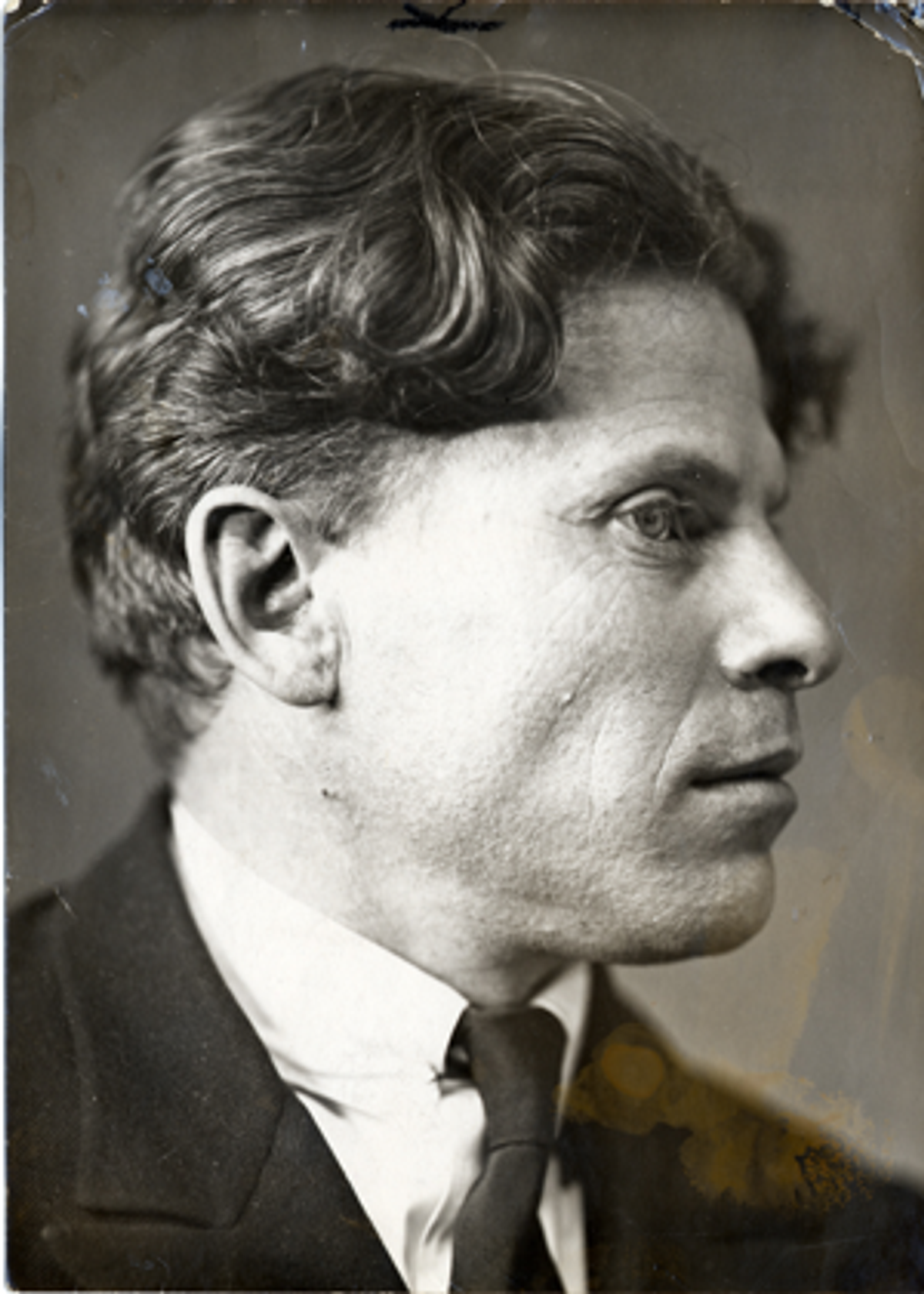

Soghomon Tehlirian, a 24-year-old Armenian student in Berlin, was a melancholy man—his former landlady would testify at his murder trial that he would sit in his room in the dark playing sad songs on his mandolin. She had learned that his entire family had been killed in 1915, but thought it best not to ask too many questions about it. She would often hear him waking up in the middle of the night with nightmares and had recommended to him a doctor who specialized in nervous disorders. Lately, he had taken up dance lessons to help calm his nerves and started to practice his German by flirting with girls. Occasionally he suffered fainting spells.

Tehlirian’s landlady was surprised when, in early March 1921, he suddenly announced he was leaving her flat to move into a new apartment on Hardenbergstrasse near Berlin’s zoo in the upscale Charlottenburg neighborhood. Tehlirian explained that he was moving because his doctor had recommended that he find an apartment with more natural sunlight. But in truth Tehlirian moved because he had learned that a man he had never met who went by the name of Ali Salih was living across the street from the apartment he had just rented, and Tehlirian had decided to murder him.

Ali Salih was the assumed name of Talaat Pasha, the former interior minister and last grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire. One hundred years ago today, on April 24, 1915, Talaat oversaw the arrest of hundreds of leading Armenian community members, a step generally regarded as the first salvo in the Ottoman campaign to deport Armenians from the Anatolian Peninsula, thus beginning the Armenian genocide.

On March 15, as Tehlirian was reading in his room, he glanced out his window and saw Talaat on the balcony of his apartment. He explained to the court that he recognized the man from having seen his picture in the newspapers. He kept watching and then, “I saw Talaat, the man who was responsible for the deaths of my parents, my brothers, and my sisters.” Tehlirian grabbed the loaded pistol he kept with his underclothes in a trunk, ran after Talaat, and fatally shot him. At the sound of gunfire, a crowd descended upon Tehlirian, beating him and holding him down. Witnesses reported that Tehlirian tried to break free, declaring, “I am an Armenian. He is a Turk. It is no loss to Germany.” Tehlirian would later tell the court that he remembered little about what happened after he fired the gun. But he did remember the sense of elation he felt upon hearing in the police station hours later that his shot had been fatal.

Armenians around the world are commemorating the genocide of their people today: Jews, who have just commemorated Holocaust Remembrance Day last week, should be doing so as well.

Armenians around the world are commemorating the genocide of their people today: Jews, who have just commemorated Holocaust Remembrance Day last week, should be doing so as well. Not only because of a shared humanity. Not only because Jews and Armenians are the two victims of genocide that gave this crime its name. But also because of the stark parallels between our experiences.

Writing in the racialized language of the time, U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire Henry Morgenthau, who was also a prominent Jewish activist, noted of the Armenians: “There has been considerable intermarrying with Jews and that by this time there is a decided strain of Jewish blood in them. I asked about this because they all look like Jews and have the same characteristics, the same stubborn adherence to their past and religion and a strong race pride.” Morgenthau was the first major international figure to alert the world to the Armenian genocide. In 1919 he would also head a commission to Poland to investigate the pogroms against Jews.

***

In that same year, on the opposite bank of the Black Sea, in newly independent Ukraine, anti-Jewish pogroms erupted in a manner parallel to what had happened in Anatolia. The list of pogrom perpetrators was expansive and diverse, encompassing foreign armed fighters, Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary organizations, ordinary Ukrainian peasants, military units loyal to the deposed Russian tsar, and Red Army soldiers. But popular memory put the blame for the bloodshed on the figure of Symon Petliura, the leader of the so-called “Directory” government that tried in vain to rule over Ukraine and establish a left-leaning national republic. Despite offering broad autonomy to the Jewish population—the Directory even printed currency in Yiddish and promised Yiddish-speaking telephone operators—the government was unable or unwilling to stem the violence. In total, over one thousand separate incidents of anti-Jewish violence were recorded; a Soviet investigation put the death toll at over 100,194. Other observers estimated that up to 200,000 Jews were murdered.

In an eerie echo of Tehlirian’s assassination of Talaat Pasha, the Yiddish poet and watchmaker Sholem Schwartzbard took his revenge on Petliura, who had fled Ukraine and was living in Parisian exile. Throughout the spring of 1926, Schwartzbard would wander through the streets of Paris’ Latin Quarter with a pistol in his pocket and a photo of Petliura he had clipped out of the Grand Larousse encyclopédique. The blond 31-year-old poet, who courtroom reporters would later comment looked more like a clerk than a murderer, short and “undistinguished in appearance,” drew no attention to himself as he sought out Petliura from among the crowd, comparing the features of likely candidates to the photo in his hands. Schwartzbard found his target on several occasions, but each time Petliura was surrounded by his wife and children.

Finally, on May 25, Schwartzbard encountered Petliura alone on the corner of Rue Racine and Boulevard St. Michel. Still unsure if he matched the photo, Schwartzbard asked the man, “Are you Petliura?” He didn’t answer. The poet took a chance and shot the former head of state five times. When police arrived at the scene, Schwartzbard was waiting for them: “I have killed a great assassin,” he declared. The crowd began running toward Schwartzbard, beating him, but the gendarme took Schwartzbard by cab to the station. Upon learning that the man he had shot was, in fact, Petliura, Schwartzbard was overjoyed.

Sholem Schwartzbard had been a struggling Yiddish writer and anarchist activist. Born in 1886 in Bessarabia, Schwartzbard was raised in the Podolian town of Balta, a town with a history of pogroms. Three of his siblings and his mother died when Sholem was a child; Sholem was apprenticed to a watchmaker soon after his bar mitzvah. As a youth, he became involved in anarchist circles, agitating for the overthrow of the tsar. Once, when he was distributing literature inside a beit midrash, the pious Jews trying to pray got fed up with him and denounced him to the authorities. He was arrested but managed to flee in 1906 across the Austro-Hungarian border, where he continued his anarchist activities.

He was arrested again in Vienna on the charge of robbing a small wine bar. He was found in the bar at opening time, having apparently locked himself inside at closing the night before. The till was short, and Schwartbard was carrying a tool kit and cash. Nevertheless, he claimed it was a case of misidentification. After serving four months for the crime, he moved to Budapest where he was again arrested, this time for distributing radical literature. He relocated to Paris in 1910, where, during World War I, he served first in the Foreign Legion and then in a regular French infantry brigade. He was injured in the war and awarded the Croix de Guerre.

But the revolutionary cause remained dear to his heart. Upon hearing news of the overthrow of the tsar in Russia, Schwartzbard returned to Ukraine in the summer of 1917, just as the Russian Empire was breaking up in a bloody civil war. He floated through several revolutionary fighting brigades, eventually finding his way to Odessa, which was from November 1918 to April 1919 under French occupation. Soon after the French abandoned the city, Schwartzbard joined the Bolsheviks and traveled with a brigade to the pogrom-devastated regions around Cherkasy. Disillusioned and traumatized, he returned to Paris, where, under the penname of Bal-Khaloymes (the Dreamer), he published vignettes about the pogroms and a series of poems about the war. He seemed to give up his anarchism and devoted himself to fixing clocks in a small shop—until he found the photo of Petliura in the encyclopedia and became obsessed with the idea of killing him.

Schwartzbard’s obsession, though, was somewhat misplaced. Although Petliura had been nominally in charge during the period of the most rampant anti-Jewish pogroms, his responsibility for them was, at best, indirect. Various warlords controlled most of Ukraine for much of 1919. Petliura’s government could hardly retain control of a single city let alone the entire Ukraine. At times he and his top officials lived in a railway car so they could relocate at a moment’s notice to whichever region his troops controlled at the moment. His proclamations condemning pogroms were as toothless as the secret orders his critics believed—but could never prove—he issued permitting them.

Schwartzbard’s act of vengeance threw him into headlines around the world and brought global attention to the pogroms and the fate of the Jewish people in Ukraine. Emma Goldman published appeals on behalf of Schwartzbard and urged American Jews to contribute to his legal defense. Historians Simon Dubnow and Elias Tcherikower compiled information on the pogroms to provide to Schwartzbard’s lawyers. Yiddish writer Sholem Asch, already known for his controversial hagiography of Jesus of Nazareth, wrote that Schwartzbard’s sin was “a redemption for us all.”

Hannah Arendt was more sympathetic to the lone assassin. Both Tehlirian and Schwartzbard, she argued, sought justice, not revenge. Rather than run from the police, she continued, they waited to be caught in order to force a trial and establish a public record of the genocide. Both courts obliged, putting Talaat and Petliura on trial as much as Tehlirian and Schwartzbard.

Juries acquitted both the Armenian student and the Jewish poet, and the public trials of the two brought the crimes they were avenging to global attention.

One Jewish law student in Warsaw at the time, Raphael Lemkin, followed both trials with rapt attention. Tehlirian, he wrote, “upheld the moral order of mankind,” and Schwartzbard’s act was “a beautiful crime.” Lemkin, who later coined the term “genocide” and lobbied for its recognition at the United Nations, was one of the first to publicly link the Ottoman attacks against Armenians with both the pogroms and the Holocaust. When CBS commentator Quincy Howe asked him in 1949 how he became interested in the topic, Lemkin replied, “Because it happened so many times. It happened to the Armenians, and after the Armenians, Hitler took action.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jeffrey Veidlinger is Joseph Brodsky Collegiate Professor of History and Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan. He is the author, most recently, of In the Shadow of the Shtetl: Small-Town Jewish Life in Soviet Ukraine.

Jeffrey Veidlinger is Joseph Brodsky Collegiate Professor of History and Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan. He is the author, most recently, of In the Midst of Civilized Europe: The Pogroms of 1918-1921 and the Onset of the Holocaust.