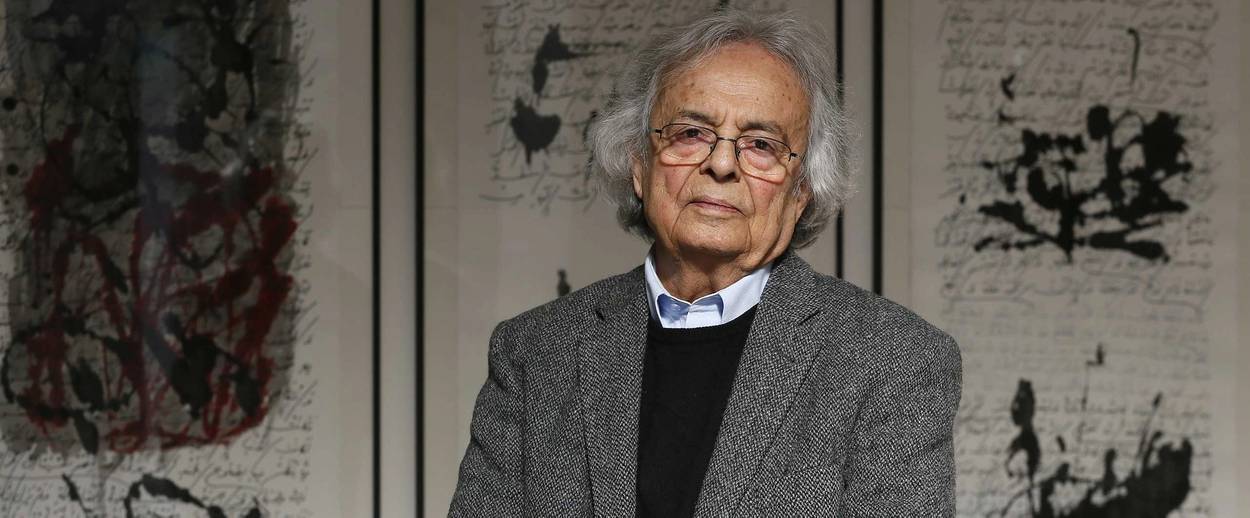

Adonis in Jerusalem

A Syrian-born poet resembles Arab literary men of the ancient past

This is the second of a two-part essay on Saul Bellow in Jerusalem. Read part one here.

I have become an Adonis-reader. Sometimes I have read him in English translations from the Arabic by Khaled Mattawa, Samuel Hazo, and other translators. But mostly I have turned to the French versions. Adonis was born in Syria, but his political activities led him to flee to Beirut in the 1950s, and from there to France, where he has been prolific. Steadily his books in their French translations have spread across the bookstore shelves, not just collections of random poems but one volume after another in complete editions, presented by a variety of translators under what appears to be his own supervision, and sometimes with his own collaboration, too—such that, to my eyes, Adonis might almost be considered a poet in French, and not just in Arabic.

So I bought his new book, Jérusalem. It is a single long poem with the city as his theme. Adonis is in general a lucid and accessible poet. Only, I found the book about Jerusalem to be a bit opaque—which made me wonder if my command of French is perhaps insufficient. A year later Mattawa came out with an English translation under the more exotic title Concerto Al-Quds, and he provided a number of clarifying footnotes, too. But the opacity of the poem turns out to be the same in French and in English.

What is it with book-length poems about Jerusalem? It is not just Torquato Tasso and his too-many hundreds of pages of Crusaders and Saracens. Glumly I have failed to make my way through Melville’s giant poem, Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land, from 1876. Hundreds of pages of compressed rhymes (“Ay, and Chateaubriand, he, too, / The Catholic pilgrim, hither drew”) jingle in the ear, which becomes unbearable. Adonis’s Jerusalem poem is in free verse and much shorter—a mere 68 pages in Mattawa’s English version. But, then again, the way to make sense of the Jerusalem poem is by reading it in the context of his larger work of recent years, which is a gigantic free-verse opus on themes of Arab history called Al Kitab, or The Book, translated into French as Le Livre, in three fat volumes. The three volumes add up to something vaster than Tasso’s poem and Melville’s combined. It is something like Victor Hugo’s The Legend of the Centuries, except bristly with scholarly footnotes and marginal gloss—thrilling and alive with the voices of ancient poets, but also dense and puzzling for large sections at a time. This may be one more effect of the Jerusalem sky.

The sky is, in any case, Adonis’s starting point in his Jerusalem poem—except that, instead of being Isaiah’s garment of God, as Bellow would have it, the sky in Adonis’s poem turns out to be the roof of a Jerusalem puppet show. This sky is anything but transcendental. The sky is an oppression, and Adonis is furious at it from start to finish. Some of his fury is political in a conventional sense, directed at the Israelis and the Jews, not just in connection to the one city but to Israel as a national project—a country founded on crime, as he pictures it.

He quotes a horrendous passage from Leviticus granting the Hebrews permission to enslave the neighboring pagans, with an inference that, in our own time, this sort of thing has governed Israel’s treatment of the Arabs. He quotes Habakkuk predicting woe to the injust. He implies an Israeli failure to build bridges to the Other (which suggests, at least, that building bridges to the Other would be possible and desirable)—though he never gets around to suggesting that Arabs build bridges to their own Other, who are the Jews. The poem does acknowledge, at least, that Jerusalem synagogues are more than a modern phenomenon.

But the poem is not really a political statement. It is a surrealist outpouring of thoughts and angers, which turn out to be recollections of texts, sometimes identified, and sometimes not—quite as if Adonis is still another Chateaubriand, for whom the universe is a vast library of well-thumbed books, which in this instance are the Hebrew Bible, the Qur’an, the sayings of Muhammad, the pensées of Nietzsche, lines from James Joyce, and passages from Arab poets and scholars of the ancient past. The quotations and references are not always comprehensible, but, if you allow yourself to submit to his words as they come, you begin to understand that he is, fact, conjuring a conflict. And yet, the conflict is not finally the one over populations and geography.

It is a conflict over freedom of thought. The puppet-show that enrages him at the start is a three-headed theocratic tyranny, signifying all three of the monotheistic religions—though naturally he is principally engaged with Islam. His objection to official religion is not ultimately different from Sari Nusseibeh’s objection to the tyrannical qualities of dogmatic beliefs. He pictures a head imprisoned in a cellar of words it has invented, which is Nusseibeh-like of him, except that he gives a name to the imprisoning beliefs. The name is Jerusalem itself, or al-Quds.

He addresses the city directly. In Mattawa’s translation:

What if we counted the skulls that tumbled and rolled (in your name) into history’s tunnels and coliseums? Will they not be enough to raise another sky the size of our sky?

Shall we say then, “Blessed be the heavens whose thirst cannot be slaked except with earthly blood?” And shall we say, “Blessed be this earth that can only praise the heavens by being another graveyard?”

The poet says to Jerusalem:

Have the skies wronged you? Or do you know a greater sinner, more arrogant and more lethal than yourself, al-Quds?

He is mordant:

They have become excellent at taxidermy.

They do not only embalm bodies they embalm

minds and ideas and now they intend

to embalm light not only

exterior light but also the light of inner life.

“No one can vanquish us”; this is how they describe themselves.

He pictures a rebellion against the tyrannical beliefs, which is a great theme of his books of the 1960s and ’70s, Songs of Mihyar the Damascene and Singulars, his masterworks. It is a poets’ rebellion, and quite an old one, too, beginning with the classical Arab poets of ancient times. It is an angry rebellion. It is not exactly an atheist rebellion, nor is it a rebellion in the spirit of the European Enlightenment. It is something else—libertarian, radical, sexy (an important quality, throughout Adonis’s poetry), and even religious, except that Adonis conceives of a religion all his own.

In none of this does he share the anxieties that pull so insistently on Bellow in Jerusalem—the anxiety about not being able to succumb to the nonrational experiences of earlier generations. Adonis has fashioned for himself a mythology of the Arab literary past that is flexibly modern and ancient at once—a tremendous achievement, which he has done in his anthologies and French translations of the ancient Arab poets, and has done a second time in his volumes of the 1960s and ’70s, and has done a third time in the opacities of The Book and the book-length poem about Jerusalem. The achievement allows him not just to resemble the poets of the ancient past, but—here is the miracle in the poetry of Adonis, our contemporary—to be one of those poets himself, a man of classical times.

He is someone like Imru-Ulquais from the pre-Islamic era, a marvelous poet of love (as we Adonis-readers know from his anthology of classic Arab poetry) who shows up in the opening section of the Jerusalem poem, quite as if, in Adonis’s world, it is normal for the most ancient of poets to trespass across the living page. And from his standpoint in a world that is ancient and modern at the same time, Adonis points his accusatory finger at the source of the modern oppression. He concludes with these caustic lines (in my translation of the French translation):

And you, Hell, in what heaven do you reside?

From what heaven do you descend?

It is a jeer at official theology—not just at one theology, but at the lot of them, the official religions, each with its own horrible heaven. A surprising conclusion to a book about Jerusalem!

And, having had his say, Adonis affixes to his Jerusalem poem, in its French edition, the date of March 2012, and the place of composition, which is Paris, where he makes his home. In this way he resembles Bellow, who, having had his own say, brings To Jerusalem and Back to a close by announcing a return to his own home, which is Chicagoland. These literary pilgrims may not share a lot, but they share, at least, a final impulse, which is to slam their books shut with farewell amens that invoke the relentlessly nonsupernatural world—the real-life alternative to the eternal exhaustion that is Jerusalem.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.