Against Politics

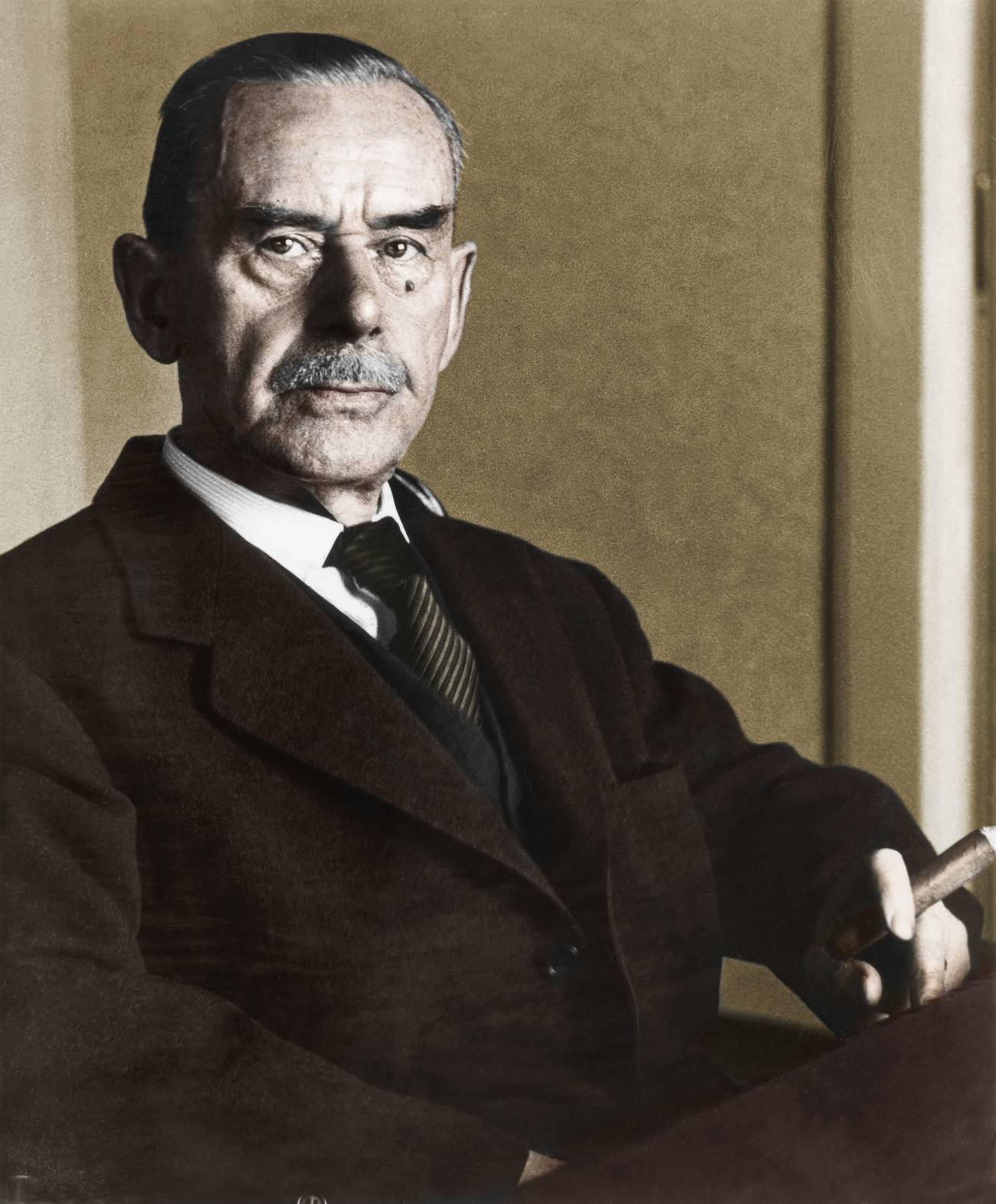

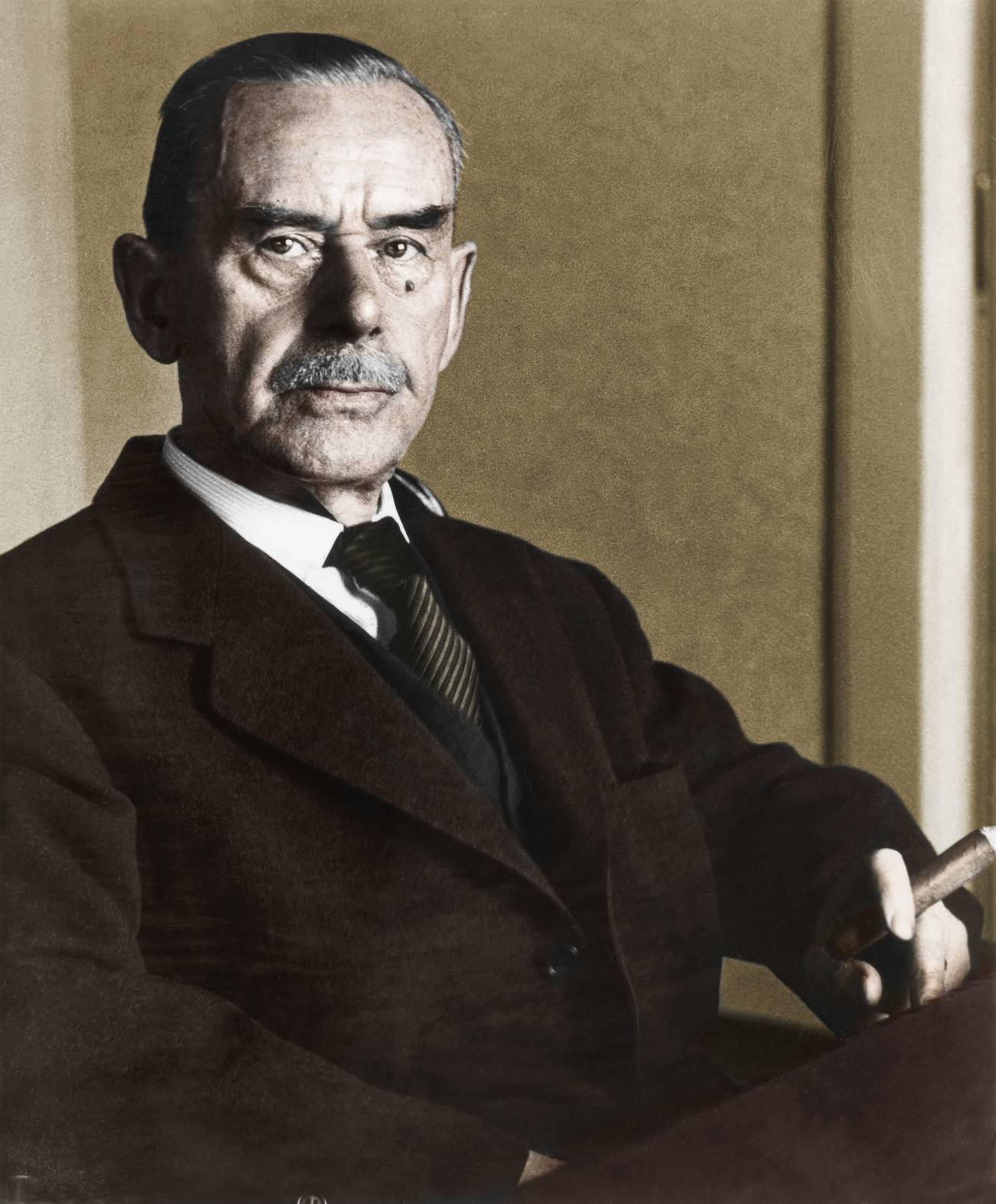

Communists and fascists are very often the same unpleasant people, wrote Thomas Mann—literary champion of the German bourgeois. He was right.

“Germany declared war on Russia. Swimming lesson in the afternoon,” Franz Kafka famously wrote in his diary on Aug. 2, 1914. Thomas Mann couldn’t have read Kafka’s words, but during his wartime exile in Los Angeles he jotted down something similar in his own diary. Mann’s entry for Aug. 6, 1945: “Went to Westwood to buy white shoes and colored shirts—First raid on Japan using the energy of the split atom (uranium).”

The many denizens of Twitter who like to ravenously screech that everything is political would no doubt be quick to judge Kafka and Mann. What monsters of vanity they were, thinking about swimming and (colored!) shirts while the world around them was being laid waste! But cordoning off the personal from the political, even in times of war and mass death, is a necessity for a writer like Mann or Kafka. These artists of illness and isolation never stopped imagining worlds apart: a burrow; a castle; a mountaintop sanitarium; deathly, plague-soaked Venice. Mann’s children called him der Zauberer, the magician. His inner sanctum, the study with its implacably closing door, was rarely violated.

Mann would have a hard time surviving present-day America, where we have all been ordered to surrender our entire brains to politics—and to hold nothing back. The meaning of the things we do or say is relentlessly referred back to our gender or skin color, both of which have become just as omnipresent and ever-malleable keystones of political propaganda as the divide between workers and bourgeois parasites was in the old Soviet Union. Who you are is rapidly being replaced by what you are, for the convenience of Facebook’s capitalists and BLM’s moralists alike.

For that reason, the restlessly gnashing thousand-mouthed social media barracuda will probably pay no attention to the recent reissue of Mann’s Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man by NYRB Press, with a new introduction by Mark Lilla, and new translations of two more essays by Mann—and therefore won’t notice how effectively Mann’s book crushes some of their most cherished and central assumptions.

In Reflections, Mann takes an ornery stand on behalf of Germany during the First World War, arguing bitterly against his brother Heinrich, who opted for France. Heinrich, who saw French civilization facing off against German barbarism, was the social justice warrior; Thomas was the conservative, skeptical patriot. Thomas sardonically quipped that for Heinrich, a renowned novelist in his own right, French bombs were reasonable and peaceful, while German ones were mere savagery.

Reflections takes up arms for the nonpolitical. Mann combats the insistence on turning every human affair into a parlor crusade where partisanship rules and enemies are satisfyingly bashed. The chief liberal slogans—democracy, human rights, freedom—come under close and rather unfriendly scrutiny. At one point, Mann even declares himself a monarchist.

Reflections remains an embarrassment to those who want to see Mann as a steadfast apostle of liberal democracy and its various causes. The usual tactic is to call Reflections an aberration corrected by Mann himself after World War I, when he became a defender of the Weimar Republic. But Mann’s tome, cantankerous and unwieldy as it is, can’t be shrugged off so easily.

Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, Mann said, was “no book and no work of art.” He was right. The volume, which came out in October 1918, when it was clear that Germany was about to lose the war, veers wildly from one subject to another. Mann is too often fumbling, strident and self-conscious, but if the reader sifts the book for gems, she will find them. Here is one:

Complete justice, with no injustice remaining, is simply an ideal goal that can only be approximated. If, for example, injustice is thrown out from one side, it slips in again from the other, for injustice is deeply embedded in the human character. Also, all experiments here are dangerous, because one is dealing with the most unmanageable material, the human race, which is almost as dangerous to deal with as high explosives.

Mann disapproves of America’s progressive push “to let pure, unalloyed justice rule” via state power. The United States, Mann remarks, is rife with “base utilitarianism, ignorance, bigotry, conceit, vulgarity, and simple-minded veneration of women, there is also enslavement and mistreatment of negroes, lynch law, unpunished assassination, the most brutal of duels, open disdain for justice and laws, repudiation of public debts, shocking political swindle of neighboring provinces, continually increasing mob rule, and more to boot.”

Our list of sins is hard to beat, today as in Mann’s time. Yet Americans still imagine that the state’s social engineering will make uncomplicated justice—now called equity—triumph throughout the land. Equity means redistributing goods to citizens based on their supposed victim status and punishing those who cannot claim victimhood—producing new victims and only dubious rewards for those they are supposed to benefit. If injustice is thrown out of the American house from one door, it slips in again through another.

In Reflections, Mann portrayed himself as a German burgher, inward looking and dutiful, averse to crass nationalism but eager to defend his nation in time of war. He was the spiritual heir of a long line of Nuremberg craftsmen, he wrote, hard workers who cared about their art above all else. While left-leaning humanitarians like his brother Heinrich trumpeted the universal rights of man (while simultaneously accepting France’s alliance with the arch-reactionary Russian czar), Thomas stressed how culture tells us who we are. Reverent toward German tradition, he was not ready to overthrow the past in the service of a drab new anonymous ideal in which every person was to be equal to and indistinguishable from every other. Legal personhood, he knew, cannot capture very much about human personality, since it ignores our cultural roots. Here Mann anticipated late-20-century thinkers like Charles Taylor, with his emphasis on how culture makes the self.

Mann’s trust in culture is still meaningful, but in the 21st century, culture has lost much of its holding power against the global forces that define us down into faceless persons who labor and consume. We enjoy abstract rights (often violated) to health and happiness that can seem as meaningless as the rights supposedly guaranteed by the Soviet constitution. Identity, because it is flimsy, even at times imaginary, cannot root us the way that culture could, or make a compelling argument against global capitalism, the dragon whose leveling shadow extends everywhere we turn.

From a literary standpoint, the writing of Reflections was an intermezzo, something Mann had to get out of his system before he could return to his work on his epic novel The Magic Mountain, which he had started in 1913, inspired by his wife Katia’s sojourn at a Davos sanitarium stocked with eccentric characters. Mann went back to writing the novel in 1919 and finished it five years later.

The Magic Mountain is, like Joyce’s Ulysses or Proust’s Search, a book you can settle into and make a home in. Mann’s sanitarium, the Berghof, is a cozy, uncanny world unto itself, where before you know it another year has gone by. The novel lives on quarantine time—for as the author tells us in his preface, “only thoroughness is truly entertaining.”

Mann’s genial, prosaic young hero, Hans Castorp, spends seven years in the Berghof, though the reader suspects that he never really has tuberculosis, but has been seduced by its atmosphere, which is full of illness and frivolity, deadly serious ideas, and cool flirtation. Hans is a steady, untroubled lover of routine—he always drinks a glass of porter with breakfast and then smokes a Maria Mancini cigar—and his relaxed bourgeois nature appealed to Mann, as Hans was the antithesis of his own high strung, passionate personality. The agonized 21-year-old Mann wrote in his diary, “What am I suffering from? Sexuality ... Will it destroy me? ... How can I rid myself of sexuality?”

Mann was erotically drawn toward men, a preference he apparently never acted on beyond a kiss or two; he would marry and have six children. His homoerotic desire was not repressed, he insisted in his diary: He didn’t wish to have sex with men, an act he found repulsive, but instead to adore them.

Mann’s tormented reverence for male beauty, so perfectly realized in Death in Venice, gives his work its bright erotic flame. He is a master at depicting the near-miss romances of men and women as well. In The Magic Mountain, for my money the most erotic book ever written, Mann portrays the monthslong silent flirtation between Hans Castorp and Clavdia Chauchat, a slinking, faintly louche Russian woman with taunting Kirghiz eyes and close-bitten fingernails. She is an enigma—Hans’ muse and his adversary. The sexual tension at long last leads to a one-night stand during Mardi Gras, when her punk meets his twee.

The Magic Mountain is a novel of ideas as well as eros, with Hans Castorp the model student sitting at the feet of two antagonistic debaters: Ludovico Settembrini, a gentle Italian liberal humanist, and Leo Naphta, a Jew by birth but now a fire breathing Jesuit who defends both the medieval church and the Bolsheviks, praising torture and persecution in the service of faith. Mann based Naphta on Georg Lukács, one of many Jewish intellectuals who turned to communism. He admired Lukács’ literary criticism, which he discusses in Reflections, but he was disheartened when Lukács started defending the communists’ use of terror against innocent people.

Naphta, like Lukács, traffics in paradoxes, a slippery logician with a forked tongue. “The Absolute, the holy terror these times require, can arise only out of the most radical skepticism, out of moral chaos,” Naphta terrifyingly proclaims. Settembrini’s humanism, by contrast, is mere pablum, Naphta charges, since “its sole objective was for a person to grow old, rich, happy, and healthy—period; [Settembrini] considered a philistine gospel of reason and work to be ethics.”

In 1918 Lukács was still against Lenin’s movement, though late that year he would change his mind and join the Communist Party. Before his communist conversion, Lukács wrote, “Bolshevism rests on the metaphysical notion that good can come from evil. That it is possible, as Razumikhin said in Crime and Punishment, to lie our way to truth. This writer cannot share this faith, and hence, sees an insoluble moral dilemma at the root of Bolshevism.”

By 1923, when Lukács published his magnum opus, History and Class Consciousness, he had decided that you could in fact lie your way to truth. The party’s leadership was infallible, since working-class consciousness actually resided not in the masses but in Lenin and his cronies. In History and Class Consciousness, Lukács praises the “revolutionary character of the Bolshevik ‘suppression of freedom.’” Lukács derided Rosa Luxemburg because she rejected terror and praised freedom of argument. The revolution relied on terror, and it could not afford freedom for anything else than the Leninist point of view—which would soon become enshrined and purified by Stalinist terror. Out of these necessary evils would come forth good, Lukács argued.

Lukács never recognized himself in Naphta, Mann sardonically noted in the 1940s. Lukács remarked that Naphta was a fascist, thereby missing Mann’s point completely. Naphta, alias Lukács, stands for a radical leftism which, like the medieval priesthood that tortured in the name of God, really amounts to nihilism—if human life cannot be made to serve a simplistic, violent idea, it must be destroyed as worthless.

The dystopian death cult whose spiritual outlines Mann saw in Lukács has infected societies from Pol Pot’s Cambodia to Yahya Sinwar’s Gaza. The price may be endless war, but at the end of the rainbow, they preach, stands a workers paradise or an Islamic heaven freed from the presence of exploiters and Jews. It is no accident that today’s leftists favor Hamas over democratic Israel—they recognize the affinity between theocracy and left radicalism, as did Mann when he made Naphta both a Jesuit and a Bolshevik.

Mann knew that Nazism’s seeds were deeply embedded in German history yet realized too that with the ascent of Hitler something horrifyingly new was born. On March 27, 1933, he called the Nazi victory “a revolution of an unprecedented kind: without ideas, against ideas, against everything that is good, noble and decent, against freedom, truth, and justice. Nothing comparable has ever happened in the whole history of mankind.” Hitler, Mann recognized, meant the total, disastrous triumph of politics over the whole of human existence. There was no space left for ideas, decency or truth, since these must be discovered by the private individual, whose worth Nazism had canceled.

Mann knew in Reflections that individual freedom, which he identified with the writer’s talent for playing with ideas, must stand against all political demands. It is on behalf of that life-giving freedom that Mann celebrates “art’s lively ambiguity, its deep lack of commitment, its intellectual freedom ... someone who is used to creating art, never takes spiritual and intellectual things completely seriously, for his job has always been rather to treat them as material and as playthings, to represent points of view, to deal in dialectics, always letting the one who is speaking at the time be right.”

The higher playfulness that Mann espouses in these sentences from Reflections perfectly suits his dazzling, many-faceted Magic Mountain, so different from today’s prizewinning novels, which present uplifting lessons endorsed by the socially conscious author and his or her tenure committee. In Mann, each character is right when he or she speaks, and the whole revolves in crystal. Staging a debate between two sides of himself, passionate lover and staid bourgeois, Mann the magician proves his freedom. High up there in the mountains, he remains miles above the cheap political fervor that contaminates his time, and ours.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.