On October 9, 1969, as Chicago was engulfed by the trial of anti-war radicals Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman, President Nixon draped the nation’s highest military decoration, the Medal of Honor, around the neck of Capt. Jack Jacobs.

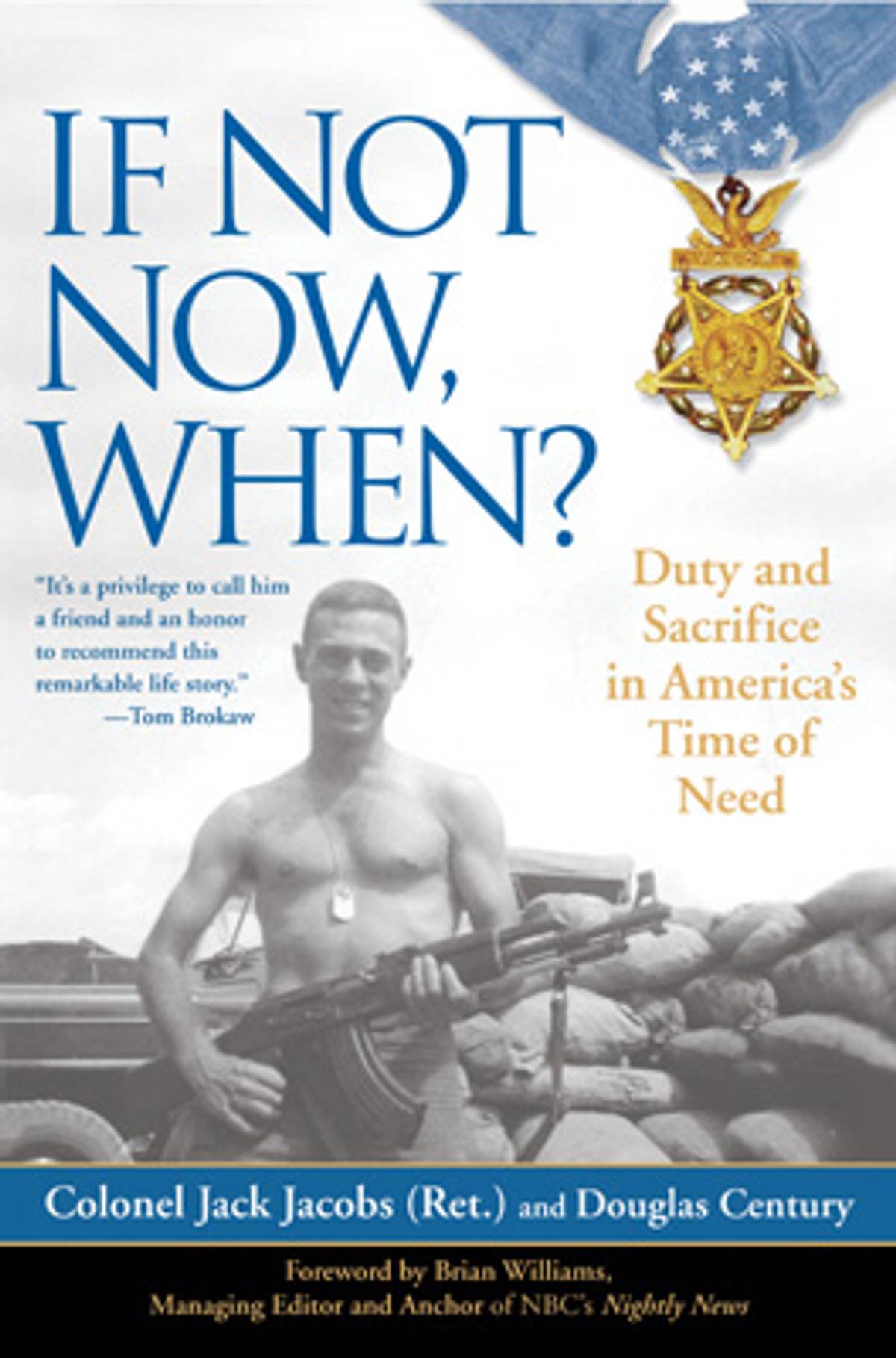

According to the citation that accompanied his award, Jacobs not only assumed command of his unit—despite suffering heavy wounds—and rescued two other soldiers but also individually repelled waves of attacking enemy soldiers: On three separate occasions, Capt. Jacobs contacted and drove off Viet Cong squads who were searching for allied wounded and weapons, single-handedly killing three and wounding several others.” Jacobs, along with co-writer Douglas Century (a specialist in the tough Jew genre who wrote Nextbook’s volume on boxer Barney Ross), has published a memoir, If Not Now, When? which employs Hillel’s aphorism to explain his wartime heroism.

The Jewish contribution to the anti-war movement has been well documented. Look no further than Rubin and Hoffman as Exhibits A and B. Not so the Jewish presence in the American military. In fact, the supposed dearth of Jews in Vietnam has drawn attention. Michael Lind in his 1999 book The Necessary War contended that, by and large, Jews avoided military service in Vietnam: Although Jews accounted for 2.5 percent of the U.S. population, Jewish men accounted for only 0.46 percent of the war-related deaths in the Vietnam War,” Lind wrote. The evident explanation for this discrepancy is the use of college deferments by the higher than average proportion of Jewish men in college to avoid military service.” This perception has been carried forward today with attacks on many Jewish supporters of the Iraq War as so-called Chicken Hawks. Such an argument even hints at the post-World War I refrain in Germany that a collection of Jews and leftists stabbed the homeland in the back.

For a variety of reasons, particularly one personal one, this point has always caused my blood to boil. My father, Gerald Gitell, served as a United States Army Special Forces officer in Vietnam in 1965. He was a member of the elite unit, informally known as the Green Berets”—in fact, he helped discover Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler, whose Ballad of the Green Berets” became the number one record in 1966. He saw and led soldiers in combat but achieved nothing near the military acclaim of the low-key and understated Jacobs. As a young boy, I became used to the fact that I had to approach him warily at night lest he leap out of bed, grunt and face me in a combat stance. Yet I never found another of my Hebrew school classmates or fellow campers at Jewish summer camp whose father had served in Vietnam, let alone joined an elite combat unit and jumped out of airplanes.

That’s what makes Jacobs so interesting: he does little to exploit his Jewishness. Jacobs is extraordinary in that he sees nothing particularly unique or interesting in that an American Jew was capable of meriting the Medal of Honor. He is, to be sure, proud of his unique Greek-Jewish heritage, writing, we are, in fact, Romaniote Jews . . . . My father’s family came from Judea, most likely 1,700 years ago on Roman slave ships which crashed on the rocks of the northern Mediterranean.” When I interviewed him recently, he put the Jewish presence (or lack thereof) in Vietnam in perspective. What seemed to be paradoxical was easily explained. It was true, he said, that few enlisted men were Jewish. The Vietnam era draft, thanks to a system of deferments, fell directly on those high school graduates who were not college bound. But among officers, who were college educated, he maintains, a significant Jewish contingent existed.

“Because Jews go to school and the focus of the anti-war movement was educational institutions, it goes to say that Jews were heavily involved in the anti-war movement,” he says. “If the locus of the anti-war movement was the building trades, you wouldn’t have a lot of Jews in it.”

Jacobs does confess that his plans to enter elect active (as opposed to reserve) service upon graduation from Rutgers University drew resistance from his parents, including his World War II-veteran father. He recalls his mother telling him, “You must be out of your mind.” His parents objected both out of a traditional Jewish skepticism of the military, hardened during the era of the Russian czars’ conscription of able-bodied Jewish youths, as well as mere career aspirations for their son. “Their faces had that sad, shocked expression that said they would have preferred I become a trash collector, or a grave digger, or a Catholic. No, I was supposed to become a banker.”

Jacobs claims he experienced little or no anti-Semitism in the military during his career, even from a sergeant major who had begun his military life as a 16-year-old member of the Hitler Youth conscripted to fight with the German army on the Eastern Front. My father, too, remembers little overt anti-Semitism. I have pressed him on this over the years. His friend Barry Sadler was known to collect German war memorabilia from World War II and even brandished an S.S. dagger he was able to obtain through song royalties. “I didn’t see any anti-Semitism in him,” my father says. “If you were a historian and into the military stuff, it was possible to be a buff without being anti-Semitic.”

Back in the late 1960s, American Jews weren’t exactly renowned for their fighting skills. Jewish service in World War II (such as my grandfather’s) had been taken for granted as part of the total war effort America waged against the Axis Powers. But Jews as fighting men still hadn’t entered the general consciousness. Israel had won its stunning victory over its Arab enemies in six days, but American Jews were seen as separate from that. Paul Breines described the prevalent post-Six Day War Jewish cultural image in his 1990 study, Tough Jews, as “the Woody Allen figure, that is, the schlemiel: the pale, bespectacled, diminutive, vessel of Jewish anxieties who cannot, indeed, must not hurt a flea and whose European forebears fell by the millions to European Jew-hating savagery.”

Given that stereotype, it’s interesting to note that Jacobs was short, less than 5 feet 4 inches tall. His book extolls the battlefield advantages of being small. (My 5-foot-8-inch father was no giant.) Jacobs is counterintuitive and interesting when he talks about another perceived Jewish trait that aided Jewish soldiers, a curious mind.

“I don’t think Jews are followers at all. We’re taught to be leaders in things. We’re taught to question. We have to think for ourselves and be creative,” says Jacobs. “Sometimes we see it in the workaday world and sometimes we see it in the government and the military.”

When I accompanied my father to his Special Forces alumni group in Las Vegas, he introduced me to a few fellow former Jewish Green Berets, none of them particularly tall. Like Jack Jacobs, they suggest that some of the most serious military men come in small packages.

Seth Gitell, a contributing editor at the New York Sun, blogs at gitell.com.