Allan Sherman’s Last Laugh

A thorough new biography chronicles the rise and fall of the big, Jewish self-destructive funnyman

Is there any lower form of comedy than song parody? Dirty limericks and knock-knock jokes may be worthless, but at least they have the decency to be brief. A parody song almost always lasts a chorus or two longer than necessary, and that’s just the beginning of the trouble.

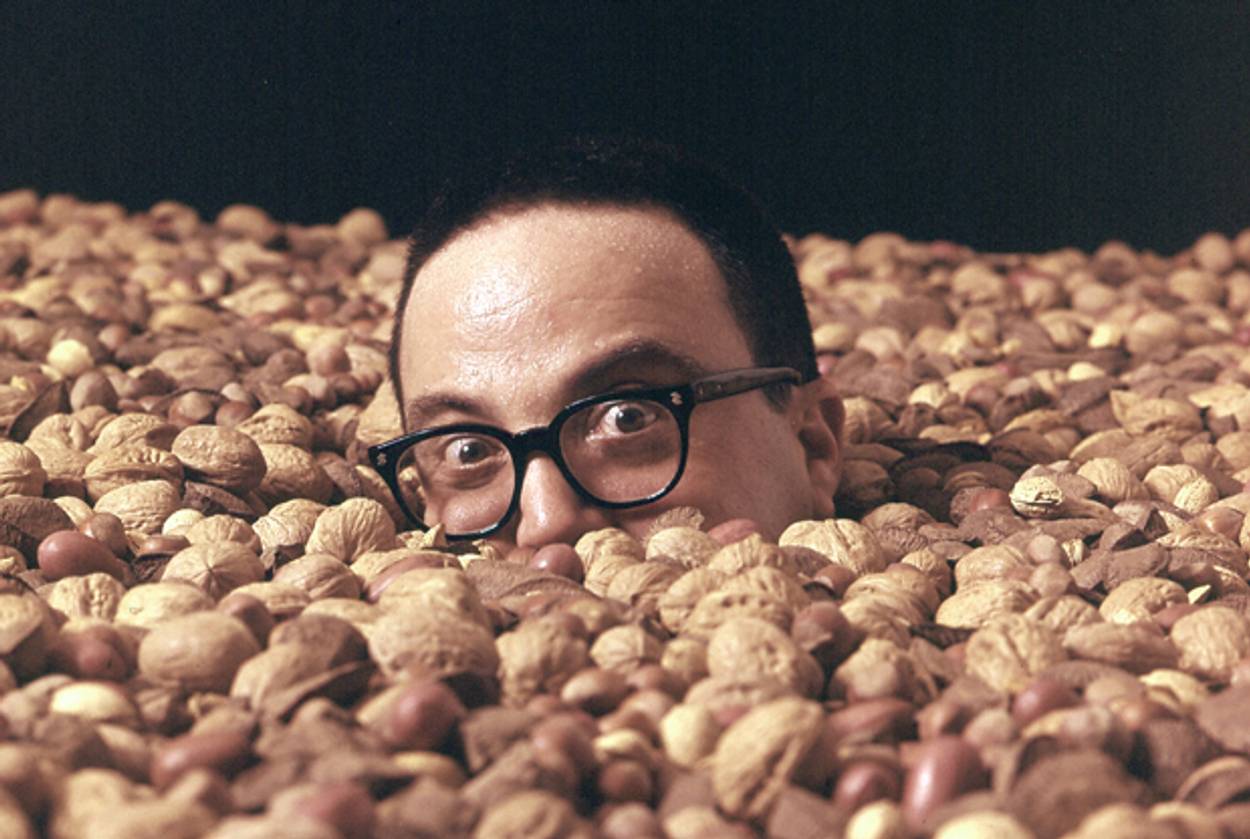

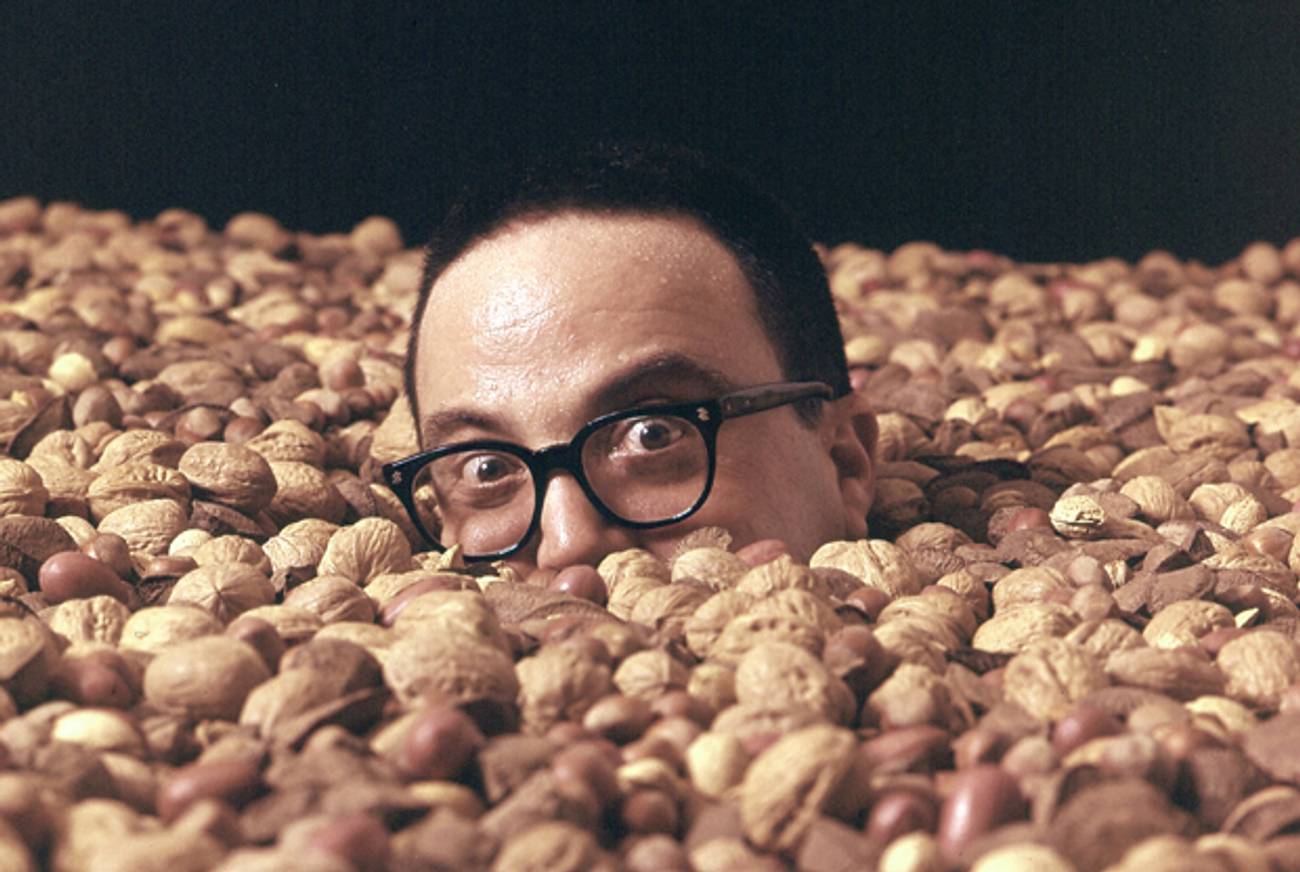

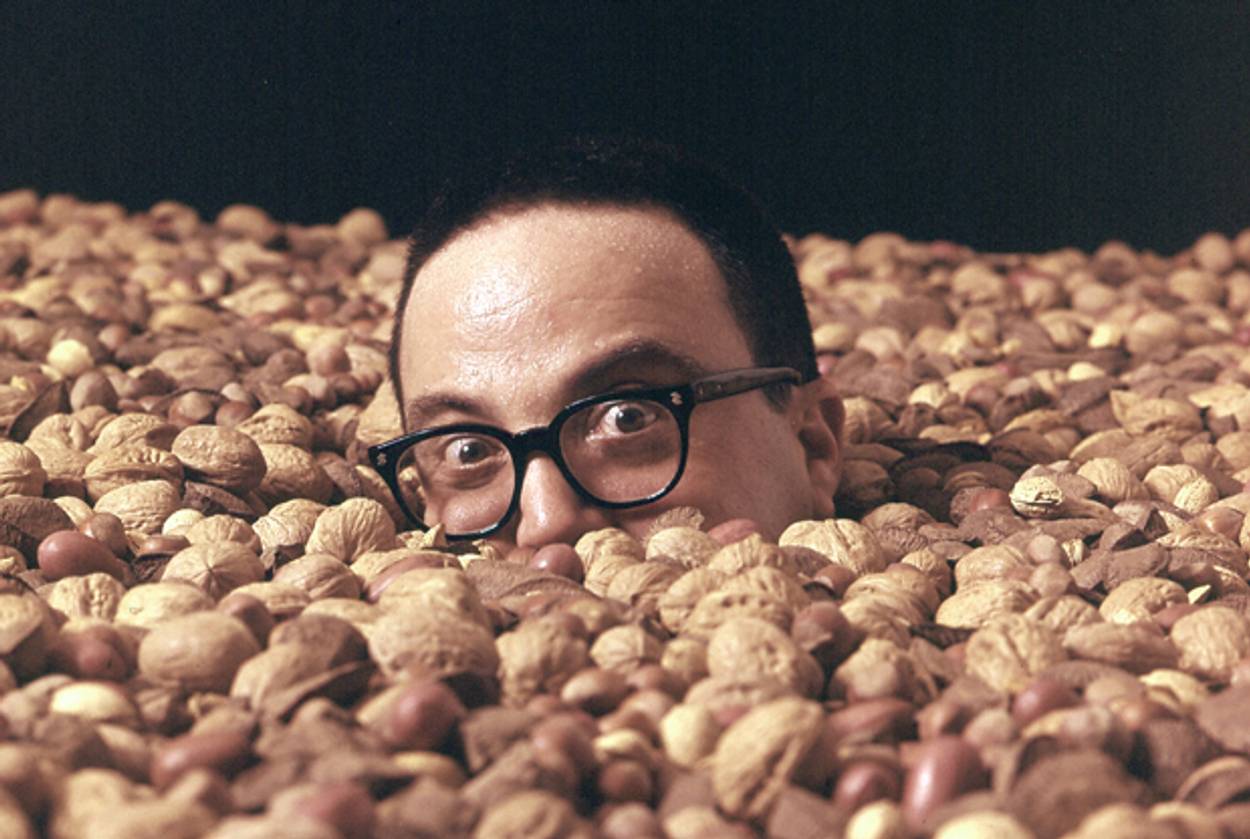

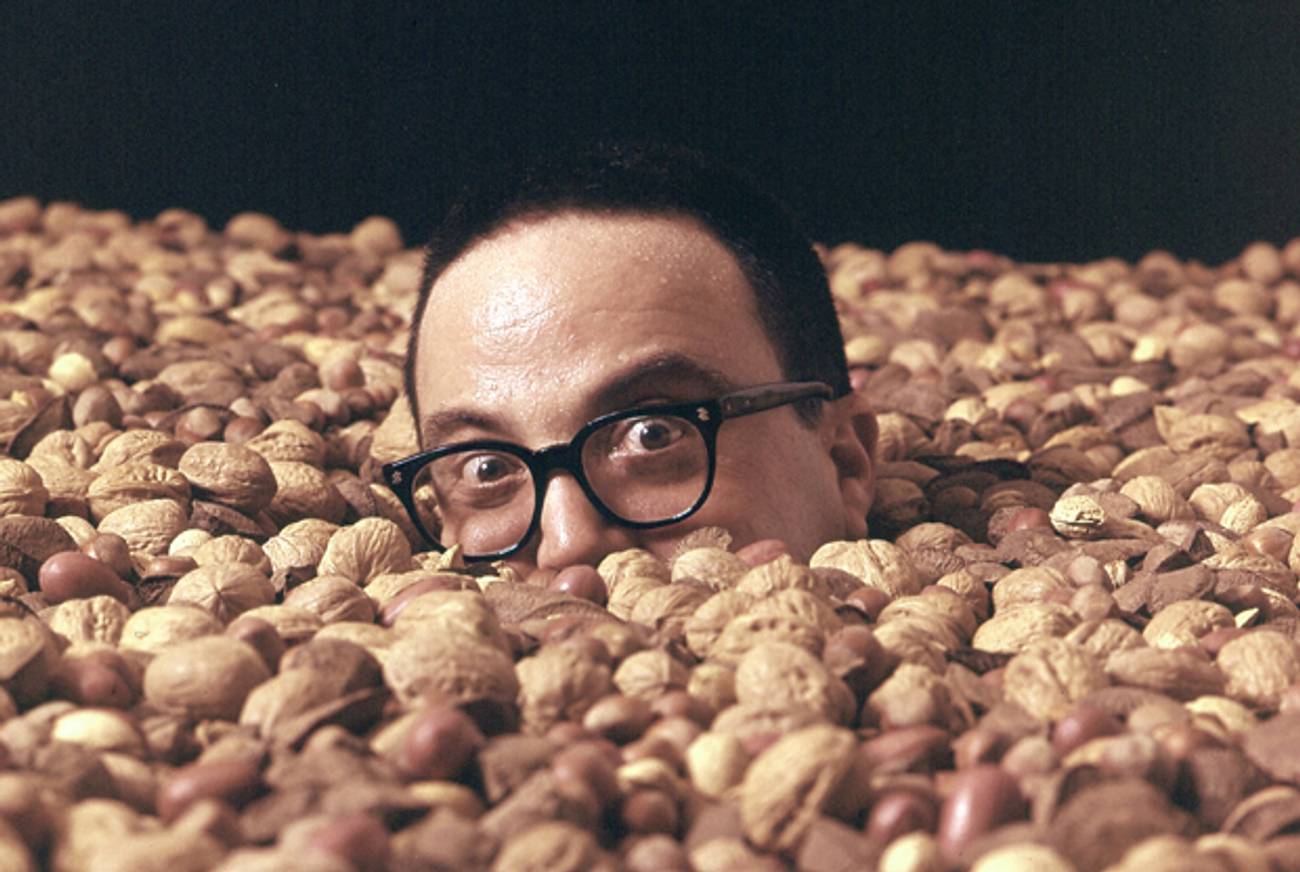

Which makes the best work of Allan Sherman all the more astonishing. Fiddling with the lyrics of recognizable songs—transforming “Frère Jacques” into “Sarah Jackman” and “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” into “The Ballad of Harry Lewis”—the heavyset, bespectacled comic turned himself into a star, sold millions of albums, won a Grammy, and headlined concerts from Hollywood to Capitol Hill. (JFK was a fan.) He also managed to say something about the place of Jews in 1960s America.

That’s why Sherman merits as scrupulous a biography as Mark Cohen has just given him, the appropriately corny-pun-titled Overweight Sensation: The Life and Comedy of Allan Sherman. And it’s why the rise and fall of a big, self-destructive funnyman fits into a series of otherwise serious academic monographs from Brandeis University Press.

***

Sherman has been rediscovered as often as he has been forgotten, but Cohen’s book is exhaustively definitive, offering enough detail to satisfy even the most annoyingly punctilious comedy nerd. Cohen has dug up every scrap of Sherman’s writing, published or unpublished, going back to his eighth-grade compositions, as well as school report cards, yearbooks, divorce papers, and even dentist registration records. Cohen actually tracked down the 1937 and 1938 Birmingham, Ala., phone books, just to let his readers know that in the latter year, Sherman’s father’s auto parts company was listed “in boldface type, a more expensive option”—suggesting business may have been picking up.

Cohen also offers up every street address at which Sherman or his parents ever lived, and how much each house cost, by way of telling the tale of a broken, bizarre family. Sherman’s parents moved back and forth across the country; after they split up, Sherman’s mother hooked up with a con artist while his obese father did something even more self-punishing. On Aug. 27, 1949, he embarked on a 100-day fast in a tiny custom-built house hoisted atop a 20-foot metal pole in Tarrant City, Ala. This was national news of the wacky variety, until the stunt killed him.

Sherman had good reasons to be cynical about familial relationships and the promise of adulthood. But there can be upsides to having lunatic parents: While pawned off for months at a time on his grandparents in Chicago, Sherman learned Yiddish expressions and the behavioral patterns of immigrant Jews and their communities, and he drew from that well when he sat down to put together a quick album of public-domain song parodies in the summer of 1962. By then, Sherman was a veteran TV hack; he had produced game shows and award shows and buddied up with celebrities including Jack Benny, Harpo Marx, and Steve Allen while entertaining friends privately with his parodies. On Aug. 6, 1962, he gathered an audience, served them drinks, turned the microphones on, and started doing his shtick.

The result was My Son, the Folksinger, and it sold 400,000 copies in three weeks. Half a century later, the most striking aspect of the album is just how many of Sherman’s punch-lines are names. Just Jewish people’s names, sung fortissimo. On the tracks, you can hear the audience responding to this, laughing raucously, whistling, pounding the floor at times. On Sherman’s parody of the folksong “Greensleeves,” he gets a 10-second laughter break after introducing “a knight who was known as the righteous Sir Green”—pause—“baum.” That’s the joke. The song ends on another joke name in the same vein: The Jewish knight retires to marry “Guinevere Schwartz.” Hallelujah becomes Harry Lewis, Harry Belfonte’s “Matilda” becomes “My Zelda,” and in “Shake Hands With Your Uncle Max,” Sherman spins out a dizzying list of Jewish family names with irrepressible ebullience:

Merowitz, Berowitz, Handelman, Schandelman,

Sperber and Gerber and Steiner and Stone,

Boskowitz, Lubowitz, Aaronson, Baronson,

Kleinman and Feinman and Freidman and Cohen,

Smallowitz, Wallowitz, Tidelbaum, Mandelbaum,

Levin, Levinsky, Levine and Levi,

Brumburger, Schlumburger, Minkus and Pinkus,

And Stein with an E-I and Styne with a Y

This was a time when most Jewish comedians were still taking deracinated stage names (Allan Stewart Konigsberg, Melvin James Kaminsky, Jacob Rodney Cohen, and so on), but Sherman clearly had no shame. His own name came not from his father but from his maternal grandparents, who, he said admiringly, “were shamelessly unselfconscious about being Jewish.”

An ethnic revival had begun in America a few years earlier, and no one captured the moment better, in comedy, than Sherman. Cohen emphasizes, cannily, that what differentiated Sherman’s first albums from other Jewish song parodists, like the delightful Yiddish-and-klezmer fueled oeuvre of Mickey Katz, and from much midcentury Jewish culture in general, was that most of his humor rested not on descriptions of Jews as they had been in some imagined immigrant or old country past, but as what they were becoming in America: model suburbanites. Sarah Jackman and her relatives read John O’Hara, work for law firms and talent agencies, identify as Freedom Riders and “nonconforma”s. Sherman’s “Hava Nagila” parody, “Harvey and Sheila,” is a love story about an MIT-trained accountant and a girl who works in the clerical department of the advertising firm BBDO. If Cohen’s claim that Sherman anticipated the ethnic style of Seinfeld and Curb Your Enthusiasm seems farfetched, consider that Jason Alexander blurbed the book, and both Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David have been heard lately singing Sherman’s tunes, or his praises.

Songs that Sherman couldn’t record, for fear of getting sued, went a step further. Introducing what he called his “Goldeneh Moments from Broadway,” Sherman would explain that his Jewish versions of show tunes had been inspired by the thought, “What would have happened, how would it have been, if all of the great Broadway hits of the great Broadway shows had been written by Jewish people—which they were.” The joke was that the great Jewish Broadway composers and lyricists had rarely, if ever, written shows about Jews. Sherman presided over the return of the repressed, turning the Gershwins’ “Summertime” from Porgy and Bess into a Catskills lament, and deforming a song from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific into a paean to smoked salmon. Bootleg recordings of some of these, including a whole set of songs from My Fair Lady, survive, but others remain only as lyrics in an appendix to Cohen’s book, where they wait for some sympathetic young performer to rediscover them.

If that first album and those mostly unpublished Broadway parodies are what make Sherman worth remembering, what granted him immortality, for better or worse, were 174 seconds of goofball fun he called “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah! (A Letter From Camp)” and released as a single in the summer of 1963 and then on his third album in a year, My Son, the Nut. It was a massive hit, climbing to the #2 spot on the Billboard charts, inspiring sequels, a board game, and even a sitcom. Seemingly no talent show at any English-speaking summer camp since 1963 has ever omitted some localized version of this chestnut.

Because Cohen seems to have scoured high and low for every available snippet of Sherman’s biographical record, it seems odd that he neglects to mention one crucial source of “Hello Muddah.” Surely the song was inspired, as Cohen notes, by Sherman’s son’s unpleasant experience at a summer camp in upstate New York, but it seems equally likely that it was also Sherman’s riff on a Tonight Show bit that Jack Paar called “Letters From Camp.” In the memoir Penny Marshall published last year, she recalls that she and her brother Garry went to “a kosher camp for rich Jewish kids” despite being “neither,” and that was whence her brother derived the material—including a joke about “Camp Nehoc” being “Cohen” spelled backward—that he later wrote for Paar. Which makes “Hello Muddah” an excellent illustration of the strange place Sherman occupied. When a Jew borrows material from a show that Lenny Bruce called “very goyish,” maybe written by an Italian who got it at a kosher summer camp, and then turns it into a hit by adding a tune from Ponchielli’s “Dance of the Hours” and singing it badly—that’s America.

***

Given the variety of Sherman’s achievements—he discovered Bill Cosby, voiced the Cat in the Hat, guest-hosted Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show—the speed of his slide into oblivion is shocking. Sherman was never exactly a rock star, but he managed to flare out like one, killing himself over the course of a decade with food, drink, drugs, sex, and heartbreak. He walked out on his wife and kids. His creative output turned to junk. His Jewish material was outshined by the work of less self-destructive talents—Woody Allen, Carl Reiner, Mel Brooks—and his nonsectarian material turned out to be mostly cliché, pap, or grumpiness. His later albums flopped, his TV appearances floundered, concert opportunities dried up, and the Broadway musical he wrote closed after four performances and a withering New York Times pan. Sherman died of a heart attack at 48, in 1973, with all his albums out of print.

Cohen details the attempts to rehabilitate Sherman’s reputation with obituaries, Best Of collections, an Off-Broadway revue, etc. But the truth he won’t quite acknowledge is that Sherman was never a great comic genius, and the form he worked in—the song parody—didn’t give him a chance to be one. The reason people enjoy parody songs at all is that they’re so accessible. When you hear a song over and over, you can’t help but substitute new lyrics. A 3-year-old will do it. And can do it. That’s why parody songs are a default gesture for lame radio DJs, high-school talent shows, and viral videos, which means that a song parodist has to be truly brilliant to escape being thought of as an excited 11-year-old.

A handful of “Weird Al” Yankovic parody songs clear this bar, and a few by Tom Lehrer. If Sherman was no better, he wasn’t much worse. Along with a whole lot of forgettable silliness and a grim personal life, he left a few treasures worth preserving—and he did as much as anyone to bring Jews out of the American pop-culture closet. One can hope that, thanks to Cohen, his legacy is now safe.

***

For more of Josh Lambert’s ongoing Tablet series on Jews and comedy, click here.

Josh Lambert (@joshnlambert), a Tablet Magazine contributing editor and comedy columnist, is the academic director of the Yiddish Book Center, Visiting Assistant Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and author most recently of Unclean Lips: Obscenity, Jews, and American Culture.

Josh Lambert (@joshnlambert), a Tablet Magazine contributing editor and comedy columnist, is the academic director of the Yiddish Book Center, Visiting Assistant Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and author most recently ofUnclean Lips: Obscenity, Jews, and American Culture.