The Meanest Genius in Portland, Maine

Outsider jazz great Allen Lowe scorns his neighbors, argues endlessly with himself

The Tablet Longform newsletter highlights the best longform pieces from Tablet magazine. Sign up here to receive bulletins every Thursday afternoon about fiction, features, profiles, and more.

It was a bleak January morning in Portland, Maine. Clouds heavy with foul weather and wet snow enshrouded the city’s stern Victorian houses and dormant factories. Casco Bay, white-capped and gray and dotted with mournful tankers, blew an icy gale. In the lobby of the Holiday Inn, where I was staying, wildly cheerful out-of-towners, members of a booster club for a visiting minor-league hockey team, milled about, looking beefy and hungover. Stacks of complimentary USA Today gathered dust at strategic locations. A Mainer—I swear he was wearing a flannel shirt and one of those plaid hunting caps with the earflaps—was drunk at 8 a.m. and arguing with a receptionist that he’d accused of stealing his medications.

Allen Lowe—late-blooming jazzman, self-taught music-historian, and 20-year disgruntled Portland resident—looked downright merry. Lowe, 60, a lopsided and harrumphing grin half-hidden behind his profusion of graying hair and beard and the Brezhnev-ian shrubbery of his eyebrows, had plenty about which to be cheerful. In 2013, he published two deeply researched histories of the blues and rock ’n’ roll, Really the Blues?: A Horizontal Chronicle of the Vertical Blues, 1893–1959 and God Didn’t Like It: Electric Hillbillies, Singing Preachers, and the Beginning of Rock and Roll, 1950–1970. Critic Greil Marcus called Really the Blues? a “crucial contribution to American culture,” adding that “all those who want to see our musical history whole are in [Lowe’s] debt.” Matt Glaser, the artistic director of the American Music Roots Program at the Berklee College of Music, has also said that “Lowe knows more about early American music—the development of it, the relations between rural and urban music, white and black music, white and black repertoires—than anyone in the field, including myself.”

His most recent album, released in February, is Mulatto Radio: Field Recordings: 1–4 (or: A Jew at Large in the Minstrel Diaspora), a sixty-two-cut, four-CD whopper of a free jazz album. As is typical for Lowe, Field Recordings comes with a 32-two-page, 13,000-word treatise-in-the-form-of-liner-notes, a dense, fact-rich, at times inscrutable, musical-historical-sociological elucidation that often outdoes the song it describes. Here, for example, is a sample of the information provided for the song “Jim Crow Variations–1”:

The ties of jazz, not to mention all of American vernacular music, to dance are, of course, well known and amply documented. Of particular interest in this respect is Jelly Roll Morton’s Library of Congress lecture/demonstration on Tiger Rag. Morton demos Tiger Rag as something that came out of the old-time Quadrille, a dance which had, in its outline, a 19th-century, debutante-formal gravity. Through his auspices and under questioning by Alan Lomax we hear, on these Library of Congress recordings, Tiger Rag morph into something both very different and yet very much the same—dance music that starts to swing and gradually become jazz, yet which retains certain old-time gestures and ideas of rhythm and melody. This is the American vernacular in action, as something actively engaged in both transformation and reaffirmation, a conservative impulse overwhelmed by the idea of cultural progress (which almost sounds like a definition of African American music). Significantly, it is also a precious piece of the 19th-century prehistory of American pop and jazz.

In recognition of this intensely creative, old-time-y outpouring, the Maine Arts Commission named Lowe one of its Artist Fellows in 2012. This generous grant program includes a $13,000 financial honorarium given each year to four artists in the entirety of the state to “reward artistic excellence [and] advance the careers of Maine artists.”

Yet none of this has brought Lowe any happiness. And allow me to be plain: He is not a cult figure or an underground phenomenon or an artist on the verge. Most of his books are self-published at a self-created imprint he’s dubbed Constant Sorrow Press. He plays few gigs, none of them in Portland, where he’s burned all conceivable bridges to the local arts and music community. He conducts his scholarly work not in a university setting with access to a well-stocked library but in the cold and very messy basement of his home. He works for an insurance company.

Still, most folks given a large check earned “on the sole basis of artistic excellence” might consider an expression of gratitude and a quick sprint to the bank. Not Lowe. It seems somehow to have pissed him off a bit, or at least provoked the aggrieved sense of humor—part personality quirk, part malignant DNA strand—which may be culturally familiar to some, but apparently translates not at all into the society and community here in Maine. Lowe has called his musical projects “an argument with someone, real or imagined.” These disputes can take arcane forms—he’s had a one-way beef going with Wynton Marsalis for close on two decades—but they all serve the same function: as an opposing force that Lowe, in turn, uses to create. He strikes the world here and there until the resulting friction throws a spark, which serves as the flashpoint for his art.

Lowe has at times diverted that resulting blaze in, shall we say, rather indelicate directions. His bio on the Maine Arts Commission website includes a reference to the state’s “lack of historical awareness,” plus a bit on how the locals tend toward a form of “musical in-breeding” that leads to “the exclusion of those whose work is not immediately accessible.”

‘Through no fault of his own’ Lowe has become ‘jazz’s quintessential outsider artist.’

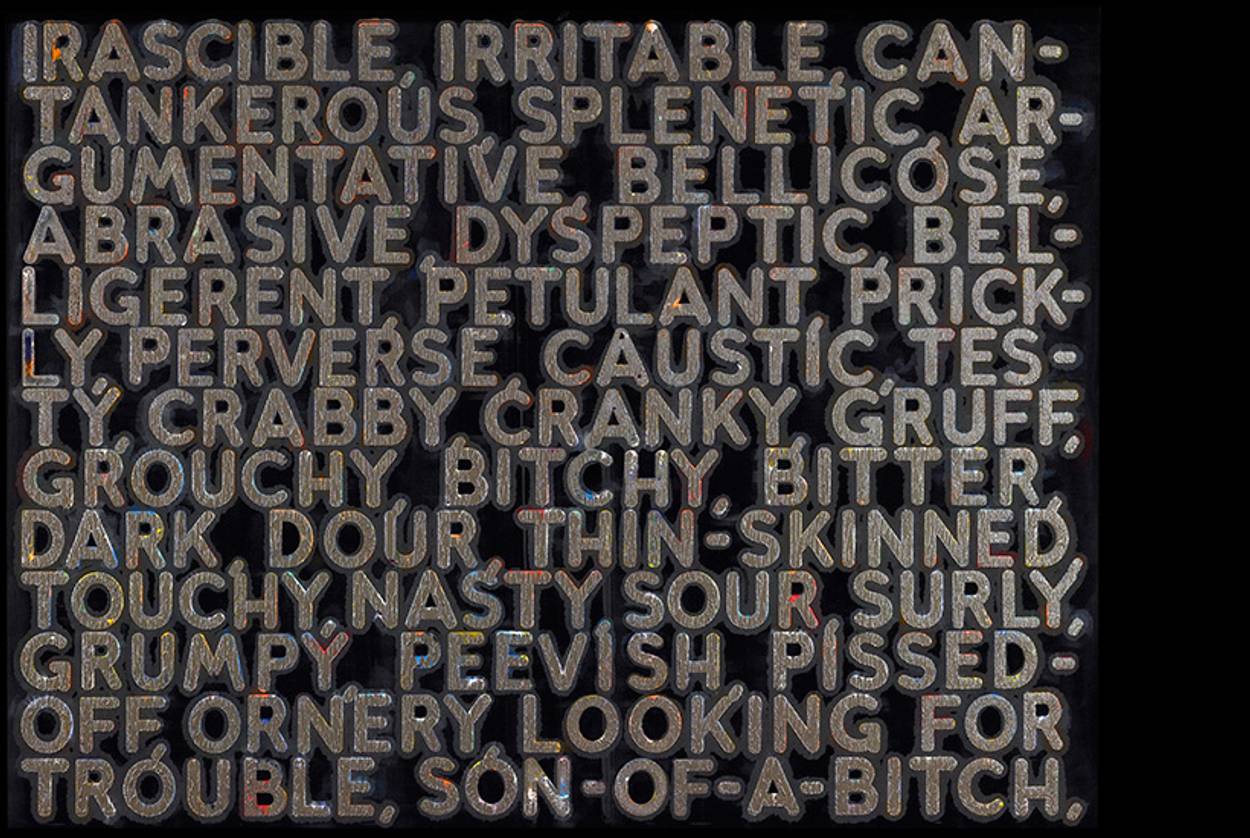

Lowe bemoans the fact that his grant didn’t result in more work in regional clubs and arts institutions. He assumed he’d finally be taken seriously and that he could play where he wanted, make a little money, make a name for himself. “But I got nothing. I’m a permanent outsider.” Just so. But Lowe bears some responsibility for that. His personal website offers this tidbit about the 2007 album, Jews in Hell (I’m going to omit the lengthy subtitle, other than to note that the hell in question is Maine and that it includes noncomplimentary references both to Stanley Crouch—long story—and a prominent Portland-based modern-arts venue): “[I]n many ways, this CD was intended as a big FUCK YOU to Maine [and] to its arts institutions.”

So, perhaps there is more than joy and amity to be seen in the face that Lowe Lowe shows to the world.

“Hop in,” he says as I let myself into his car. “I’ll give you a tour of all the places I hate.”

***

Lowe conducts me around Portland’s pleasant downtown, whipping past various clubs and galleries and other art spaces and raining amiable opprobrium on all of them. One place “won’t hire anyone over 25.” Another, which receives funding from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the Maine Arts Commission, he dismisses as no more than a spot for “bad art films.” At One Longfellow Square, a live music nonprofit, he remarks on the demise of its predecessor, the Center for Cultural Exchange, which failed in 2006. “I wouldn’t call it suicide—more like murder.” The New England Conservatory of Music won’t return an email, but he won’t be ignored. He opposes and disdains and covets approval, all at the same time.

Lowe grew up in Massapequa Park, Long Island, in a house of what he described to me as mid-century Jewish intellectual-liberals. His parents—dad a public-school teacher, mom a librarian with a doctorate—hailed from the Brooklyn folk-villages of Brownsville and Bensonhurst. Mother played piano, trained as a youth with Paul Wittgenstein, the one-armed concert pianist and brother of Ludwig, the Austrian philosopher. Lowe studied the oboe as a young child, without devotion. At 13 he spent the summer at a music-themed summer camp and afterword took up the sax. His interest in contemporary music grew.

“I was extremely lucky,” Lowe told me. “That period from 1966–’70, jazz is dying from the rise of rock ’n’ roll. For an innocent boy like me it was perfect. All the jazz records were on sale for cheap. $1.99, they’re overpriced.” He’d forage albums out of a bin at the Waldbaum’s in Bar Harbor. Chased Sonny Rollins and Charlie Parker and Ornette Coleman down the musical rabbit hole. He was particularly taken with early avant-garde. “Coltrane spoke to me and still does. I wanted something a little bit more harmonically based, a little less free, but structured.” At 15, he snuck into the city a few times with a bunch of friends, driving someone’s VW bus, to see Mingus and Ornette play at Slug’s Saloon, a legendary jazz spot on an Alphabet City block run by Hell’s Angels. Saw Zappa with his mother, Muddy Waters on the lawn at Newport, Miles Davis with his electric band, B.B. King with Michael Bloomfield at the Fillmore East. Strong sense of identification with Bloomfield, the guitarist. “We’re alike in many weird ways. A wiseass Jewish guy, never hit his stride.” He never imagined himself taking up music professionally. He just listened. Obsessively. Eight hours a day sometimes.

He went to college in Michigan, transferred to Binghamton, dropped out, took classes elsewhere, went back, finished. Went to the Yale School of Drama, for a single year of playwriting, dropped out before he flunked out, battled his professors. “Closest I ever came to taking a swing at someone was John Guare”—author of Six Degrees of Separation. Met and married his wife, an accomplished public-affairs attorney from a family of accomplished WASPs in New Haven. They moved back to Brooklyn, where Lowe acquired a master’s degree in library sciences, moved back to New Haven, where he variously sold ads for a small newspaper, worked as a librarian, ran a music festival, started a sound-restoration and audio-remastering business, got serious with the sax, gigged around town. In 1985, at age 31, he recorded his first album, For Poor B.B. and Others (that would be Bertolt Brecht), which the Philadelphia Inquirer described as “mostly slow bebop with an intimate, almost dreamlike slant.” Sales were in the vicinity of 100 copies.

Then the move to Portland—“Seemed cool. God strike me dead for saying that”—and the gigs dried up, and Lowe turned his attention to research, immersing himself in the deep annals, the bedrock strata, of American musical history, drawing associations and rendering insights that only an autodidact whose work is beholden to no one would likely make. In 2010, Greil Marcus, Lowe’s most mainstream champion, wrote an appreciation of Lowe in The Believer, praising him as a “radical pluralist” who stitched together thoughts and songs from “late-nineteenth-century black quartette singing, Bert Williams, W.C. Handy, early gospel, vaudeville blues, minstrelsy survivals … Mamie Smith, Sarah Martin … Bessie Smith, Louis Armstrong, King Oliver, and the lone-traveler-with-guitar of the country blues … Paul Whiteman, Jimmie Rodgers, white mountain singers, Billie Holiday, bluegrass, Sacred Harp chanting, Frank Sinatra, Doris Day, and a Charles Ives piano piece from his Symphony no. 1.”

Matt Glaser brings Lowe up to Berklee every once in a while to lecture to the students. Lowe plays music for them and explains it, spins associative webs from his skeins of musical silk. Glaser concedes that his students might not “appreciate the depth and range of Lowe’s knowledge.” Savor the understatement in that remark. Think of how Lowe must appear to these young people seeking accreditation in the musical establishment. He has no degree and no pedigree. Just two ears and a mind.

Lowe is like that crabby Jewish uncle of mine (or yours, or someone’s), the one who slips me a twenty at the bar mitzvah and then, a few scotch-rocks in, corners me with his tales of woe in the insurance business. Or the bespectacled, chain-smoking grandfather, the one from Minsk who managed a dry-goods store, sang like a Yiddish bird, and knew more about classical music than any schmuck on the radio. And really, is Lowe’s caustic worldview so different from any New York Jew of a certain age, one displaced from his shtetl-like homeland on Long Island and settled, forcibly or no, in a town where the bagels suck? (Of the subject of his Judaism, Lowe has this to say: “It’s safe to be a Jew with a lowercase j here. In a weird way—I’m not religious—I have a capital J. I’m so clearly a Jew, but in a way that hits people the wrong way.”) Lowe has enough self-awareness to discern a bright side to all this. “I made better music here than anywhere else,” he tells me, pausing a moment before slipping in the knife. “What else is there to do but play the piano all day and compose?”

***

Let us pull back for a moment. Allen Lowe has a nice life. He knocks off work each day at 3 p.m., with ample time to retreat to his basement lair and listen to music. Maybe no one reads his books or listens to his albums, but they exist and that is an achievement. He has a sweet house that we visit after our drive. Not too big, not too small, all the right knickknacks, lots of good books. He shares it with his wife, Helen, with whom he has two grown children and a friendly dog. There is a Steinway upright in the dining room against one wall and a few saxophones piled in a corner. Helen has a regal bearing and kind eyes. She speaks of Lowe in warm and admiring and protective tones. She grew up in a family with a “very Calvinist” background, she tells me, very “risk averse.” There is nothing of that in Lowe, and she loves it and wants to shield that quality—that lack—from the actuarial demands of the conventional world. To a question about his devotion to music, whether Lowe could function without the stability she brings to their lives, she allows only that he might lack “executive skills.” Lowe smirks at this. “I might end up homeless without her,” he says. “But I would do my projects.” Now she smiles.

In 1974, when he was 20, Lowe moved to Queens, after a short stint in Boston, where he worked at the warehouse of a local record-store chain and helped run the American Shakespeare Theater in Stratford. This was a wonderful period in his life. He had a cheap apartment in Woodhaven and an old Chevy Biscayne that he’d drive everywhere, but mostly into Manhattan to the jazz clubs. He became a regular at the Vanguard and Birdland, Jimmy Ryan’s on West 52nd, Gregory’s on First Avenue. Without quite intending to, he started making connections to the jazzmen around town. He’d approach them after sets and ask to talk, tell them he was working on a book, which was nominally true but never actually happened. These weren’t the marquee names, the ones you recognize from album covers, but second-tier craftsmen, players you know only if you pore over liner notes, listen to everything, pay attention to the granular details.

Al Haig, who played piano for Charlie Parker and recorded with Miles Davis on Birth of the Cool (and who was tried and acquitted of strangling his third wife), became a friend. So did Davey Schildkraut, whose alto sax you can hear on albums by everyone from Tommy Dorsey to Tito Puente. “One of the three, four, greatest sax players of the bebop era. Dizzy put him just after Bird.” And Jaki Byard, who played for Mingus, and whose death—he was shot in 1999—brought Lowe to tears in his living room. A lot of these guys weren’t even playing anymore. Lowe would just look them up in the phone book and call, head over to their houses with his Sony recorder and tape everything. Curly Russell (double-bass: Monk, Miles, Hawkins, Getz, Buddy Powell) was driving a cab and living with his daughter in a big old house in Queens. “Thing Curly was proudest of, he told me, ‘When Parker died, I owed him money.’ ” Tommy Potter (bass: Count Basie, Artie Shaw, Max Roach) washed dishes at the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center. Joe Albany, a pianist and heroin addict with another Bird story: “Said to me once, ‘When I write my autobiography, I’ll call it I Licked Charlie Parker’s Blood’—off the needles they’d shared.” Lenny Tristano, the blind pianist and a founding figure of free jazz who quit playing in public in 1968. Lowe visited him at his place in Jamaica Estates, Queens. Because Tristano was a recluse, it took six months of phone calls before he would allow Lowe to come by. When he finally did sit down with him in his living room, flanked by his two nine-foot Steinways, he told Lowe to put away his tape recorder. “ ‘Want you to get it right. That cocksucker Ira Gitler screwed it all up.’ ” (Gitler, author of Jazz Masters of the 40’s.) “We did this long narrative interview. School for the Blind. Taking lessons. Chicago. Something is very familiar about all this, but I’m taking notes furiously. I leave, and afterwards, I’m like wait a minute. I got Jazz Masters, and he had told me almost verbatim the same thing. It was like word for fricking word.”

Eventually he lost touch with these men, stopped haunting their doorsteps. He still has some of the tapes. Others are gone. He used the interviews to scare up a few stories in DownBeat and CMJ, but mostly he couldn’t place them anywhere. Lowe can write, so it was probably the names. Who were these people, and what was interesting about them, so far from their short time in the small corner of someone else’s spotlight? “I just wanted to talk to them about their lives,” he says. “I idolized these guys, and I was honored they accepted me as a friend. I didn’t think I was going to be a musician. It was just part of life.”

It’s not easy to place this period from Lowe’s life into context. The lessons don’t announce themselves. “I think those experiences taught me how to be a musician,” he ventures. “Even if they weren’t playing much, all they thought about was music,” he told me. “Every time I compose a tune it’s like I’m imagining these guys that I knew. It doesn’t come out like them. But it’s coming through me.”

***

Lowe has a practice session scheduled for that afternoon. We make our way through the snow to a faceless hulking duplex on the other side of town. Peter, a kid recently laid off from One Longfellow, lives here and will play drums. Him plus a standup bassist Lowe’s never met. Both are still out buying beer when we show up. A roommate squires us to the converted back bedroom and disappears.

Who were these people, and what was interesting about them, so far from their short time in the small corner of someone else’s spotlight?

The room is crowded with a drum kit, a rickety-looking upright, a stylish tan Wurlitzer, a lamp someone made out of an antique phone, some basic recording equipment, an old computer with sound-mixing software open on the desktop. Generous natural light and a square patch of dirty carpeting nailed to the ceiling (for acoustics). Posters on the wall for Lil Wayne, Deerhoof, Heart, a local arts festival, all much doodled upon. A cluttered and half-bohemian location nicely suited to the idea of some dudes working out on jazz.

Lowe gravitates immediately to the Wurlitzer as we wait, looking it over wistfully.

“Love these,” he says. “But they’re not cheap.”

I don’t say anything, but I’m getting a case of nerves as we wait. To like Lowe, to get him, enjoy him—this comes easily to me. Here’s the thing, though. I know enough about books to judge Lowe’s, and they impress. But the music? Truth be told, I’ve intentionally shied away from listening to it.

I came to Portland, in some respects, in search of my very own Outsider Artist, and so far Lowe hasn’t disappointed. The grievances, the fact of his being overlooked, the assurances from Greil Marcus and the others I’ve spoken to before coming here, bolster the case for something special lurking in the northland. The talented Jew exiled to the Taiga for crimes beyond his comprehension. He slaves away in the gulag of his day job, while at night he etches his mark on the cold and unforgiving stone of humanity.

But that narrative demands at least some proficiency with the alto sax Lowe has brought with him this day. I watch him monkey around with his reeds until Peter and the bassist show up. I remind myself that his life, the small truths of it that I am supposed to render for public consumption, do not make of me a judge or jazz critic. So, he need not be Bird or Miles (though that would be awesome), but please, please, please, please let him not suck.

Peter, when he comes, is a big fellow with an impressive hipster’s beard. He’s recorded with Lowe before and regards him with what I read as tolerance cut with respect (or maybe it’s the other way round). The bassist, a soft-cheeked boy whose paunch has grown past the confines of his jeans, doesn’t say much. Lowe distributes the sheet music, and they dive in. They sound raw but tuneful at the outset. They pass soloes around and Lowe stops occasionally, tells them what he wants and where they should go. “I want stuff to breathe,” he says. “Stop short like Mingus. Flow in a non-flowing way.”

The young guys seem a little constrained at first. Not nervous so much as uncertain. They’re having trouble getting into it, which sounds ridiculous but just means they don’t understand the music. They stumble over the changes, apologize, try again. Lowe is supportive. No anger, no frustrated self-regard. He’s wearing an old sweatshirt with the elbows patched and looks like a cross between an aging hepcat and a hermit squatting out by the docks. Eventually, though, the music catches the boys and they lose the self-consciousness. Something switches on and they can see what to do. The bassist clasps his eyes shut and his body begins moving in (awkward) rhythm. Peter breaks into a wide smile as he whacks away. He looks to Lowe for direction and they converse without speaking, through the music.

“Cool tune,” the bassist says between numbers. “I like it.” Peter agrees. They discuss something in musical jargon that I miss but that they all chuckle at.

They move on to a new tune, which Lowe describes as a “riff tune with a bridge. No repeats. Sorta works out. Gets a little bouncy to the bridge.” He calls out the tempo and off they run.

So, what of the music? Was there anything to it? Should everyone book tickets to Lowe’s triumphant return to the Vanguard? I can’t—I won’t—say. I would like to help in some way, but I’m not sure if that’s really what Lowe wants.

Francis Davis, the former jazz critic for the Village Voice, has said that “through no fault of his own” Lowe has become “jazz’s quintessential outsider artist.” And with this Lowe agrees, telling me earlier that he is “an outsider artist, but one who is desperate to get in.” But I’m not sure that he would ever voluntarily resolve the argument that comprises the entirety of his creative undertakings.

Lowe wraps up the session after a couple of hours. Some loose talk about getting back together for more practice. A discussion about recording these songs. Lowe thinks out loud about a trip down to Brooklyn to a studio in Gowanus that asks $75 an hour. Or maybe some out-of-town session players can be flattered into a road trip up to Portland.

Peter tries gently to coax Lowe into recording here in town. Grab some local talent, he suggests, talk to this club owner—someone who has thrown elbows with Lowe before—about booking his place for free.

“I don’t know … ” Lowe says.

You can tell he does, though, and that there will be no reconciliation with the artistic community of Portland, Maine. Lowe thanks Peter and the bassist, packs his saxophone, and we leave. He will make his music and write his books. He will not change.

***

Sign Up for special curated mailings of the best longform content from Tablet Magazine.

Theodore Ross, the author of the memoir Am I a Jew?, has written for the New York Times, Harper’s Magazine, the Oxford American, and other publications.

Theodore Ross, the author of the memoir Am I a Jew?, has written for the New York Times, Harper’s Magazine, the Oxford American, and other publications.