American Freedom Is Greater Than Slavery and Ends in Death

The second in a four-part investigation of our national literature

There are many ways of getting freedom wrong. For ways of getting it right, my best advice is to turn to the mainline of American authors from the cusp of the Civil War through the turn of the century. For them, freedom is not the survivalist’s barren fortress-building, the hedonist’s plot to escape the world and its obligations, or the gunman’s drive to violate that world. It’s not the power to accumulate cash or cultural capital. So how did they define this most American of words?

Walt Whitman saw freedom as release, the oneness of death that unites us all. Here was a riposte to easy patriotism, since death precedes all politics, and lies much deeper in us. For Frederick Douglass freedom was a concrete goal, the escape from slavery. Henry James described the freedom that comes with an educated awareness. Mark Twain carved his way through a frontier freedom that was spirited and raw. Edith Wharton outlined the shallow conventional life that can prevent you from being free, turning you into one of life’s victims.

At the start Henry James hated Walt Whitman. “Mr. Whitman is very fond of blowing his own trumpet,” James snickered in his review of Drum-Taps, Whitman’s book of Civil War poetry. Whitman, James charged, was “aggressively careless, inelegant, and ignorant,” and “constantly preoccupied with [him]self.”

But James changed his mind about Whitman. Edith Wharton describes him later in life reciting Whitman’s “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking,” “crooning it in a mood of subdued ecstasy till the fivefold invocation to Death tolled out like the knocks in the opening bars of the Fifth Symphony.” Hard as it is to imagine Henry James on his bike careening through the English countryside (yet it’s true—he was a fanatical cyclist), it might be harder still to imagine him intoning the plaintive words of Whitman’s he-bird yearning after its mate in “Out of the Cradle”:

O madly the sea pushes upon the land,

With love, with love.

O night! Do I not see my love fluttering out among the breakers?

What is that little black thing I see there in the white?

Unembarrassed as always, Whitman poured his soul into the he-bird’s chant, and James, with Wharton at his side, abandoned his usual high-starched quizzical manner to join in the poet’s throbbing.

Whitman charms us with his huzzahs and his many oddnesses. “Hankering, gross, mystical, nude”—so runs the poet’s self-portrait in Song of Myself. “How is it I extract strength from the beef I eat?” he asks. Nutrition, like all else under the sun, and like Walt himself, is a mystery, worth puzzling over.

When Whitman is somber, he haunts us. He notices a child wondering “what is the grass?” and muses an answer that channels Isaiah’s astounding metaphor, all flesh is grass: “And now it seems to me the beautiful uncut hair of graves.” Song of Myself turns dim and reflective as Whitman speaks lines that could have come from his reluctant inheritor T.S. Eliot:

This grass is very dark to be from the white heads of old mothers,

Darker than the colorless beards of old men,

Dark to come from under the faint red roofs of mouths.

We live in a world of the dead, Whitman is saying. Through this gesture, he skews death toward life, making it the most capacious form of our existence, the beautiful secret word that releases us. “The sea,” he writes in “Out of the Cradle” (the climactic passage that Wharton refers to), “lisp’d to me the low and delicious word death, / And again death, death, death, death, / Hissing melodious ...” Since our being is not just ego and consciousness but something that thrums beneath us as a force of union, “To die” is, as Whitman wrote in Song of Myself, “different from what any one supposed, and luckier.”

Whitman was a healer during the war, and he lovingly tended to wounded young soldiers as poignantly described by Mark Edmundson in his recent book on Whitman, Song of Ourselves. The poet was marked forever by his experience of the “camps of the wounded,” “these butchers’ shambles,” as he described them:

There they lie ... in an open space in the woods, from 200 to 300 poor fellows—the groans and screams—the odor of blood, mixed with the fresh scent of the night, the grass, the trees—that slaughter-house!

Whitman remembered too the darkest hour of the Union, the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861. Whitman was among the crowds in the streets of Washington, many despondent but others taking satisfaction in the Confederate victory. “Half our lookers-on secesh of the most venomous kind—they say nothing; but the devil snickers in their faces,” Whitman wrote, and he added:

If there were nothing else of Abraham Lincoln for history to stamp him with, it is enough to send him with his wreath to the memory of all future time, that he endured that hour, that day, bitterer than gall—indeed a crucifixion day—that it did not conquer him—that he unflinchingly stemm’d it, and resolv’d to lift himself and the Union out of it ... UNIONISM, in its truest and amplest sense, form’d the hard-pan of his character.

Whitman saw in Lincoln the indispensable man, unswervingly dedicated to union, “the foundation and tie of all,” as Whitman called it. But for the ex-slave Frederick Douglass, who tried to sway Lincoln toward a more anti-slavery posture, the president was a less essential and prepossessing figure. In his address at the unveiling of the Freedmen’s Memorial in 1876, which depicts Lincoln freeing a slave, the lion-maned Douglass bluntly proclaimed,

Abraham Lincoln was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model. In his interests, in his associations, in his habits of thought, and in his prejudices, he was a white man.

He was preeminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men. He was ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the rights of humanity in the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people of this country. [...]

Knowing this, I concede to you, my white fellow-citizens, a pre-eminence in this worship at once full and supreme. First, midst, and last, you and yours were the objects of his deepest affection and his most earnest solicitude. You are the children of Abraham Lincoln. We are at best only his step-children; children by adoption, children by forces of circumstances and necessity.

Douglass in his speech then depicts Lincoln as a Moses who was slow coming down from Sinai, bound as he was by the iron laws of politics:

Our faith in him was often taxed and strained to the uttermost, but it never failed. When he tarried long in the mountain; when he strangely told us that we were the cause of the war; when he still more strangely told us that we were to leave the land in which we were born; when he refused to employ our arms in defense of the Union [...] when we saw all this, and more, we were at times grieved, stunned, and greatly bewildered; but our hearts believed while they ached and bled.

To Douglass, Lincoln was not a sacred symbol or a saint but a flawed if necessary leader. Instead of waiting for Lincoln to emancipate him, Douglass achieved his own freedom, not just by escaping to the North but by expunging all traces of the slave in his psyche. Each memory of slavery’s scars was painful to him. In his 1845 autobiography Douglass, who was soon to become the most celebrated orator in America, recalls the singing of slaves making their way to the Great House Farm, their master’s home plantation. “While on their way,” Douglass writes, “they would make the dense old woods, for miles around, reverberate with their wild songs, revealing at once the highest joy and the deepest sadness ...” These songs show the “horrible character” of slavery as nothing else can, Douglass says—presumably including gory scenes at the whipping post—because the slaves cannot completely reject the master’s values. They too are proud of the Great House Farm.

If Douglass were to keep listening to the slaves’ music, his soul would be tarnished, his will made weak. His idea of freedom, wedded to a blunt Christian honesty, is not musical but moral. Here, Douglass turns his back on the blues, which comes out of the field songs he portrays. With hard-earned irony, the blues makes terms with misery and even finds exultation in pain. We admire Douglass’ heroic conception—but sometimes we still want to hear the blues.

William Dean Howells once asked Mark Twain, “Why [do] we hate the past so?” Twain responded, “It’s so humiliating.” Twain’s Huckleberry Finn magically turns every humiliation into a game, from the threats Huck endures at the hands of his drunken murderous Pap to the ritual demeaning of Jim by Huck and Tom Sawyer at the book’s end, when they fool Jim into thinking he is not yet free—hijinks that sour the conclusion for some readers.

Many of Huck Finn’s glories are hard-edged, like the feud between the Shepherdsons and the Grangerfords, a frightening piece of satire from Twain showcasing the brutal consequences of gentlemanly honor. And there’s the cold-blooded killing of a reckless blowhard named Boggs, celebrated by townsfolk in the old-fashioned equivalent of a Twitter frenzy. Twain loves to dissect con men, like the Duke and the Dauphin, but their antics turn pathetic quickly. “Stand up for the stupid and crazy,” Whitman said, presaging the Beats, but in Twain’s work, the stupid and crazy tend to be scoundrels. The best part of Huck Finn is what everyone says it is, the scenes of Huck and Jim lying on their raft:

Sometimes we’d have that whole river all to ourselves for the longest time. Yonder was the banks and the islands, across the water; and maybe a spark—which was a candle in a cabin window; and sometimes on the water you could see a spark or two—on a raft or a scow, you know; and maybe you could hear a fiddle or a song coming over from one of them crafts. It’s lovely to lie on a raft. We had the sky up there, all speckled with stars, and we used to lay on our backs and look up at them, and discuss about whether they was made or only just happened.

It’s likely that soon Huck Finn, felled by the ideology of anti-freedom, which presents itself as a shield against harm, will no longer be taught in our schools. Yet it will always find readers, because of passages like the one I’ve just quoted.

Henry James was Twain’s opposite number. Where Twain pretends to be rude and untamed, James is judicious and evasive in his manner. Both were great experimenters, forecasting the modernist adventures of the 1920s that I will talk about in my next article in this series.

James is our great novelist of renunciation, which is not usually considered an American virtue. In his most accessible masterpiece, A Portrait of a Lady, which, like Huck Finn, was first published in the 1880s, James seduces the reader into thinking that this will be a story about imagination and freedom, not renunciation, but in the end his heroine, the inimitable Isabel Archer, gives up romantic love.

All James’ novels feature an electric-wire sensibility. His characters are constantly alert, and at times quivering with alarm. James portrays an exhilarated awareness piqued by danger, whether the danger is the specter of social ruin, being tricked into or out of love, or being shown up in front of the internal jury that rules on the legitimacy of one’s self-image. This darting psychomachia is a heightened form of life, a virtual reality. No one misses a move.

James’ knowing style, with its precision which may occasionally seem preening or archly tut-tutting, is easily parodied. But it allowed James to let loose his energies and be superbly creative. This style, oblique and cutting, was his invented personal signature, and astoundingly enough, it was the way James spoke, too.

The young lady of the Portrait, Isabel Archer, is drawn so that every reader will fall in love with her. She is quick, alive, and open, and above all free, with an American’s hunger for new experiences. The leisurely opening of James’ novel acquaints us with Isabel’s capacious and acute way of looking at the world. “She had an immense curiosity about life and was constantly staring and wondering,” James writes. “Her deepest enjoyment was to feel the continuity between the movements of her own soul and the agitations of the world.” Still more charmingly, Isabel, James remarks, “had an unquenchable desire to think well of herself. She had a theory that it was only under this provision that life was worth living.”

Isabel gives herself proper credit, the first prerequisite of freedom. But she steps into a trap. James, as usual, has something up his sleeve—a nightmare marriage.

The Portrait of a Lady contains a puzzle to thwart readers: Why does Isabel choose to marry the serpentlike connoisseur Gilbert Osmond, a louche American expat, instead of the most wholehearted and simpatico of her suitors, Caspar Goodwood? (A solid name, that, made for gripping firmly in hand.)

Goodwood is simply too plain, too much there, unlike the chiaroscuro Osmond—he gives Isabel nothing to figure out, no material to work on. As the critic Robert Pippin remarks, when Goodwood makes his final try for Isabel, after her marriage to Osmond has collapsed, he is the same “earnest boy” he always was, only more assertive. Pippin notes, “There is something pathetic and paradigmatically American in Goodwood’s claim: ‘Why shouldn’t we be happy—when it’s here before us. When it’s so easy?’”

When they embrace, Isabel senses Goodwood’s “hard manhood” like a flash of lightning (James added this sensational phrase when he revised the novel for the New York edition of his works). Yet she rejects a relationship with him. She didn’t and doesn’t love Goodwood, but is merely excited by him, and excitement is not enough.

At the end of the Portrait Isabel narrows the circle of her interest, which has earlier been so ample and free-swinging. By facing her fate, instead of fleeing it with Goodwood, Isabel survives. She returns to Rome, the site of her marriage to Osmond, perhaps to confront him or to rescue Osmond’s daughter Pansy—only the all-seeing author Henry James knows for sure, and he’s not telling us.

James’ Isabel has her dark double in Edith Wharton’s Lily Bart from The House of Mirth. Where Isabel wants to see and experience beauty, Lily aspires to be a beautiful object, admired like a jewel in its setting. “She could not figure herself as anywhere but in a drawing-room, diffusing elegance as a flower sheds perfume,” Wharton writes. Yet despite the shallowness of her dream Lily does not seem at all trivial to us—a miraculous achievement on Wharton’s part.

Lack of money haunts Lily and finally does her in, with a directness matched only in Dreiser. Her grand desperation and tragic death are set off against the fine sensitivity of Laurence Selden, the man who should have married her but who instead remains a mere observer of her career. Selden is kind to her, as is, surprisingly, the Jewish social climber Rosedale. Wharton began writing Rosedale as an antisemitic caricature, but then turned him into a mensch. But kindness is not enough. Lily is simply unequipped for life, shortsighted and full of wrong instincts. “She had never learned to live with her own thoughts,” Wharton notes piercingly about Lily.

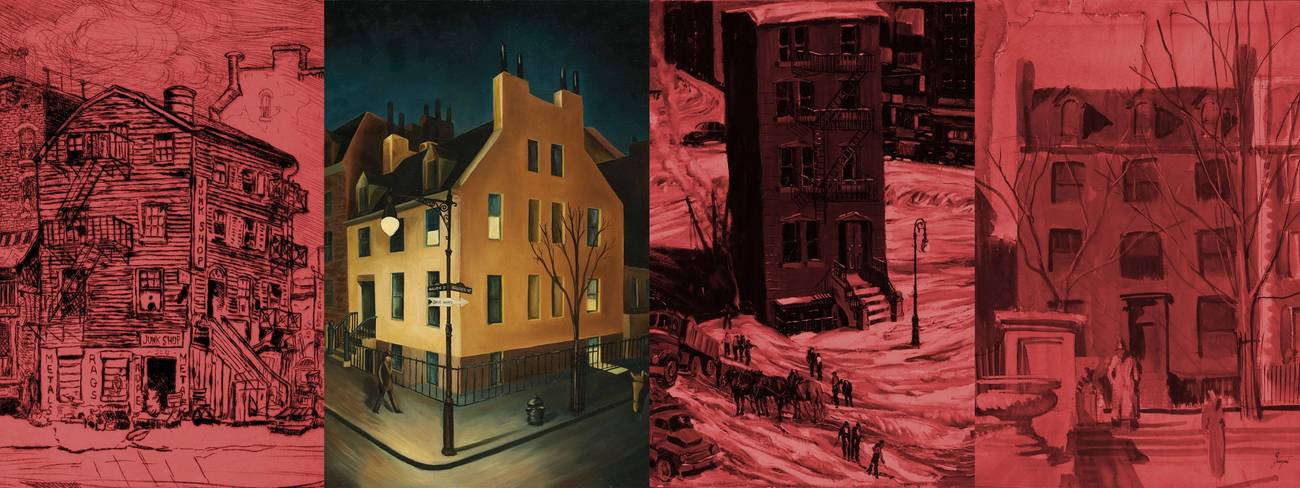

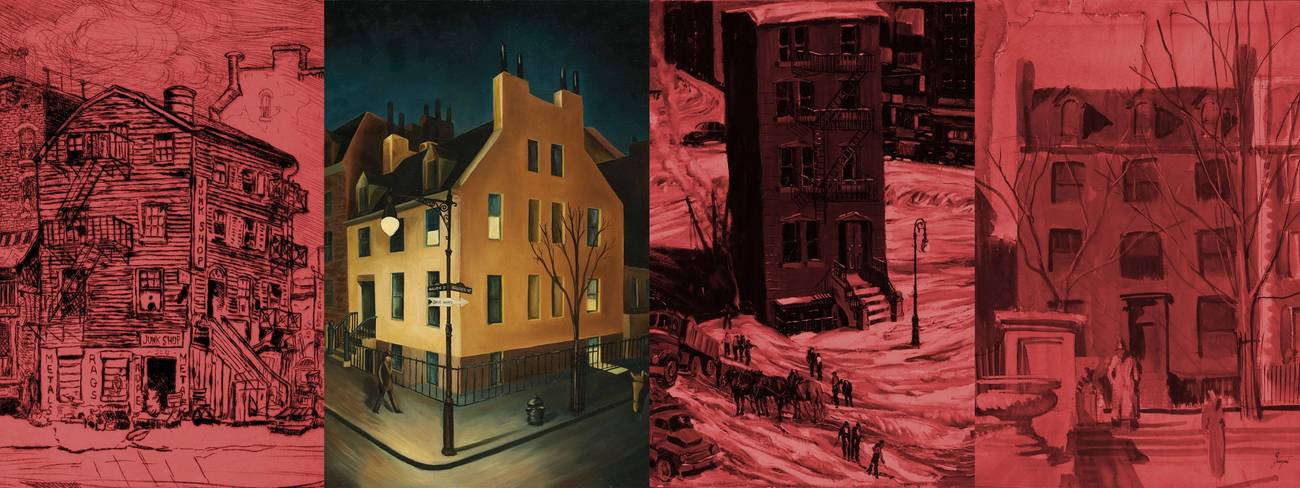

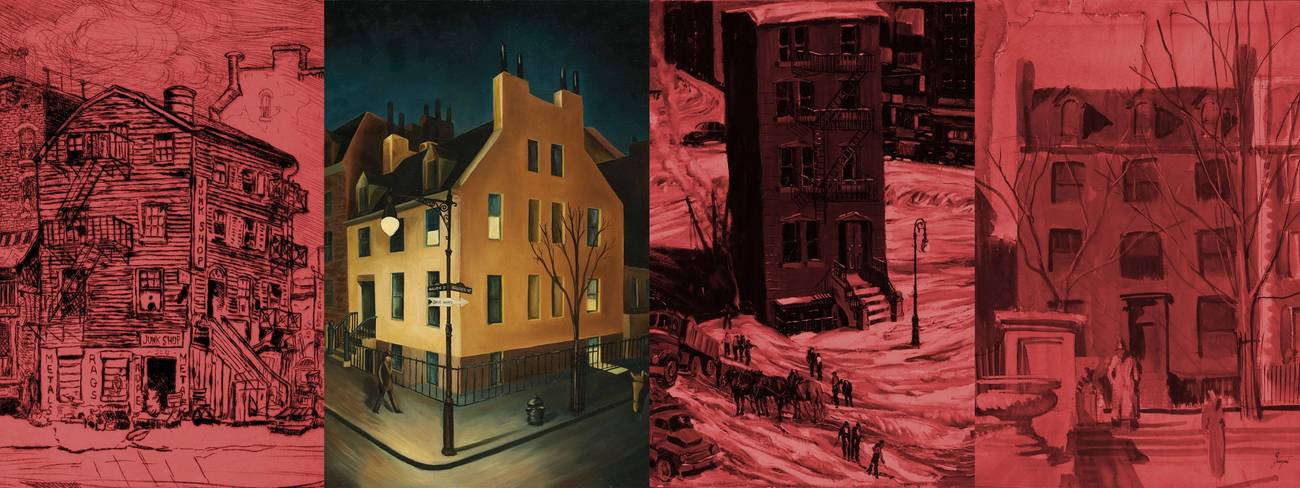

James advised Wharton to “do New York”—and she did. Her unsparing account of the city’s ruthless upper classes in The House of Mirth and an even more brutal novel, The Custom of the Country, shows how money, personal appearance, and sexual availability imprison young women. For Lily there is no way out—but Selden the aesthete memorializes her from the sidelines. In the end, disquietingly, Selden congratulates himself for having loved Lily, almost as if savoring the fact of her ruin.

For James’ Isabel, freedom meant conceiving the world so that doing what you like and doing what you ought become one and the same. It’s the noblest combination imaginable, but there is something childlike about it. Lily Bart in The House of Mirth represents the crashing of such dreams into the hard reality of the American drive for success. Freedom is a way of shaping the self, which Isabel can achieve and Lily cannot.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.