Monumental paintings adorn every wall of Hyman Bloom’s house in Nashua, New Hampshire—a fluorescent rabbi at the main entrance, a dark nude of an old woman just off the kitchen. It’s been 65 years since Bloom made his momentous leap onto the American art scene. He was 28 when the Museum of Modern Art selected him as one of 18 new artists to be featured in the exhibit “Americans 1942.” Critics applauded his work, struck as much by his vibrant use of color as his subjects: aging rabbis, an exotic bride, a chandelier from his childhood synagogue. Equally impressed were Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, both in their 30s and yet to embark on the work that would make them famous. De Kooning would later tell Bernard Chaet that he and Pollock considered Bloom the first Abstract Expressionist in America. But while Bloom’s paintings soon hung alongside theirs at the 1950 Venice Biennale, few people today have heard of him.

That may be remedied, in small part, by “A Spiritual Embrace,” a rich and surprising exhibition of Bloom’s work running at the Danforth Museum of Art in Framingham, Massachusetts until March 11. It comes only five years after a retrospective at the National Academy of Design, but includes ten previously unseen portraits of rabbis, only a sample of at least 40 that Bloom has painted in the last fifteen years. They most closely resemble the uncomfortable, unsparing portraiture of Lucian Freud, all wrinkles, flesh, and shadows, but Bloom’s brushstrokes are thicker and more spontaneous, as though he were at war with the canvas. To see them forces a reframing of his career—not as an Expressionist who found his style memorializing a world he had abandoned, but one still grappling with people and places he never escaped in the first place.

Bloom was only seven when he and his parents left Lithuania for Boston. Now 93, he dismisses the recent round of attention as “a lot of nonsense.” Sitting at the kitchen table, he takes an occasional bite of banana from the plate in front of him, and listens with an impish grin, his gray beard only a few inches shorter than those of the rabbis he used to paint and still sketches. Stella, his second wife, 30 years younger and Greek, with smooth gray hair and glasses, says it’s one of his bad days, and goes digging for his hearing aid. When I thank him for making time to speak with me, he laughs, “Think nothing of it. You’ve just kept a dying man from his bed.”

Death is not a new concern for Bloom. Many critics have seen echoes of Parisian Expressionist Chaim Soutine’s work in his painting. But while Soutine was content to paint animal carcasses hanging in butcher shop windows, Bloom took one dreary step further, depicting human corpses torn open, chests gaping wide. He seems at once invested in exposing the sad tangibility of the flesh, and offering a glimpse of something beyond, something he may or may not believe in. “I just have no particular need to go to the synagogue, confess my sins,” he says. “I don’t think I’m talking to anyone.”

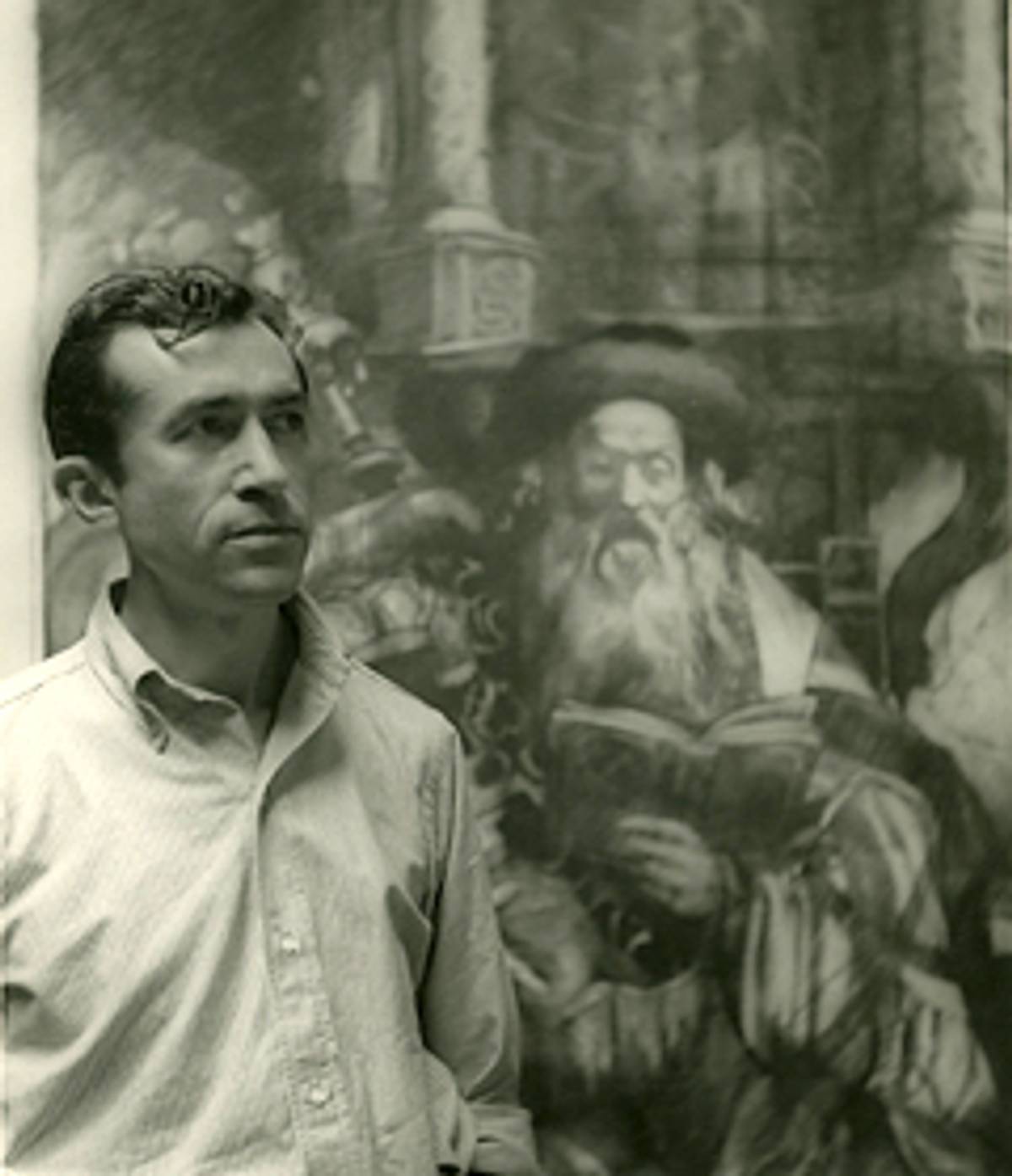

Bloom’s agnosticism makes his obsession with rabbis especially mysterious. He has often insisted that the rabbis are simply good subjects, only to hint, at other moments, at a deeper resonance. With a slight smirk, he says, “I’ll tell you a secret. I had a melamid, a teacher, in the old country, and he asked me what I wanted to be in the United States. I told him I wanted to be a rabbi, and he gave me his blessings.” In fact, the story’s no secret. Bloom has told it many times before, pushing critics, curators, and viewers to read the rabbis as shadow selves, or doppelgangers—representations of the man Bloom might have become. (He has, in fact, several photos around his studio of himself modeling, posed as a rabbi, wrapped in a tallis.) The rabbis, he says, “represent the best that can be made of a human being, and so, at least in my mind, that’s what they represented when I was a boy. And even if they don’t live up to that standard, they still have a symbolic value.”

Asked why he never joined the rabbinate, Bloom answers, “Because I didn’t have any pupils.” The reality is more complicated: After arriving in America, Bloom’s father tried to enlist a Hasidic rabbi to tutor him, but he could only find someone to take the boy through his bar mitzvah. It was soon after that Bloom began another sort of training. Boston’s elite, along with its more established Jewish community, set up classes and schools to turn the city’s greenhorns into true Americans, and Bloom won a scholarship to take drawing classes at the Museum of Fine Arts. And it was at the West End Community Center, where he attended classes at the same time, that he met Harold Zimmerman, the instructor who taught him to paint not from real life but from memory and imagination.

It’s a method that Bloom’s never abandoned, and one that’s led to the mesmerizing paradox at the heart of the rabbi portraits—they remember keepers of a tradition in a method that tradition expressly forbids. As Bloom explains, age and illness endowing his voice with a hoarse, prophetic quality, “Jewish culture has nothing to do with painting. That’s a rule, ‘Thou shalt not make an image of anything in the air or on the earth.’” Nor is there anything sweet or sentimental in Bloom’s style. In a pair of rabbi portraits from 1955, you can practically see Bloom in his studio working out his style, moving between the Abstract Expressionism he pioneered and a more classical, figurative mode. Both paintings depict elderly rabbis enthroned with Torahs on their laps, robes and tallit trailing to the floor. But in one, every inch, even the rabbi’s wrinkled face, is suffused with yellows and oranges, and the Torah is wider, taller. It feels less like a nostalgic reverie than a fever dream.

It’s this portrait that blurs the boundary between reality and imagination, and points to Bloom’s later works, dark in style and subject, including not only autopsies, fish skeletons, and gnarled forests but the astral plane, a hellish dimension of demons straight out of Pan’s Labyrinth. These stem from Bloom’s study of Theosophy, an occult religion dating back to the 19th century that once counted H.G. Wells and Kandinsky among its followers. While living in Boston, he was even a regular at séances, but Bloom says he never found any medium who could produce a physical manifestation. Not that it stopped him from imagining more: the Danforth has on display several breathtaking canvases depicting spirits rising out of bodies, the sort of supernatural visions at the root of much of Bloom’s art. Asked to name the artists who’ve inspired him, Bloom mentions the British Romantic painter J.M.W. Turner. “He was always dealing with fantasy, like hope.”

While Bloom’s work attracted attention for decades—the Whitney hosted a retrospective in 1954, and an exhibit of his drawings in 1968—by 2002, when the National Academy of Design decided to curate a series of shows celebrating “once renowned artists whose careers have fallen into relative obscurity,” he seemed an appropriate place to start.

“There was a period of about six months where Hyman Bloom was the most important painter in the world, and probably a period of about five years where he was the most important painter in America,” says Katherine French, director of the Danforth Museum and curator of “A Spiritual Embrace.” But while museums including the MoMA, the Whitney, and the MFA have paintings by Bloom in their permanent collections, “most of them are in storage,” says French.

Some critics would say Bloom’s style simply went out of fashion—Clement Greenberg was never a fan to begin with, and while Pollock and De Kooning pushed art further into the stylistically abstract, Bloom’s work remained more figurative. But the better explanation for his fall into obscurity may be Bloom’s own reluctance to show and sell his work. Already in 1942, Time described him toiling away in a Boston studio, warmed only by a kerosene stove, “uninfluenced by other U.S. artists, indifferent to both money and publicity,” and he hasn’t changed much since. Though he had dealers up until 1986, later when gallery owners and curators would come to the house, he’d turn his paintings to the wall. “To him the most important thing in his life was to paint, to have enough money to live and paint. He didn’t care about fame,” says Stella Bloom.

While most artists hold on to few works—witness PS1’s current “Not For Sale” exhibition—the racks in Bloom’s studio are full of giant canvases he considers incomplete. “Even now, none of the work is finished,” says Stella. “If you show him something from 40 years ago that a museum owns, he says, ‘Oh, the hands are not right, the head, the eyes, the cloth is not folded right.’ There’s always something that he could do to improve it. I said to him. ‘Thank god, we did not have any children,’ because he would have never let them go.” It’s only in the last two years, since Bloom’s fallen ill, that he’s allowed Stella to show and sell his work to visitors.

After 45 minutes, it’s clear Bloom is too tired to continue, and Stella helps him to his walker and leads him through the living room into his studio. It’s nearly the size of a barn, and littered with enough books, papers, and pictures to make it look like Bloom’s worked there for decades. In truth it was built only five years ago as a more spacious alternative to the narrow studio on the third floor, but, as Bloom’s found it more and more difficult to climb the stairs, it’s become his primary workspace. In one corner lie a pair of Torah covers and a shtreimel, a fur hat worn by members of some Hasidic sects. Below the window sits a twin-sized bed. Tenderly, Stella tucks Bloom in for his afternoon nap, pulling the blanket up to his chest, his shoes still on.

As Bloom’s gotten older, his rabbis have seemed to age, too—growing ever more frail, skeletal, and ghostly, and, at the same time, more flamboyant in their colors and brushstrokes. In the last two years, he’s lost the energy to paint, but he still does at least one small drawing in a notebook every day, usually after sunset (he’s always preferred to work at night). Many of the sketches depict rabbinical students with their books open, sometimes reading, sometimes dozing. In others they talk with demons and goats, as though the rabbis were sitting down for a conversation with the residents of the astral plane for a meeting between human and animal, spiritual and bodily.

The old studio upstairs, where Bloom’s worked for most of the thirty years he’s lived in Nashua, practically overflows with remnants of his career. Over the railing hangs another pair of Torah covers; on a table sits a surburhar, a stringed Indian instrument which resembles a sitar on steroids, that Bloom once learned to play; while many more “unfinished” canvases stand facing the wall.

The studio contains another unexpected clue about Bloom’s rabbis: photos of favorite artworks are taped to the cabinets, including a painting by Matthias Grunewald of Christ nailed to the cross. The way Jesus’s head keels to one side echoes a pose in one of the rabbi paintings at the Danforth, and makes clear how earnest Bloom was when he called rabbis the “best that can be made of a human being.” The rabbis, like Grunewald’s Jesus, carry a burden—the law, at once majestic and almost too heavy to bear—but they refuse to let go. And in a strange way, Bloom, whether he won’t or simply can’t, has never let go either. Like the ghosts of the séance paintings, ghosts Bloom never actually saw, the rabbis are a sort of wish fulfillment—a dream of spiritual grandeur that Bloom hopes for, and wants us to hope for, even if it remains, in the end, a fantasy.

For those who resist or deny those consolations, and the tradition Bloom’s rabbis uphold, the portraits can also inspire something like guilt—something uncanny in Freud’s sense of the unheimlich or unhomely, when something secretly familiar and repressed resurfaces. What’s so unsettling about the rabbi paintings is that they feel like a memory pulled from some cultural unconscious and made visible. Maybe the rabbis are Bloom’s doppelgangers, but they’re many other people’s too—the ghosts of the past resurrected, asking us once more to reconcile our present with the places left behind, a world as enchanting as it is grim.