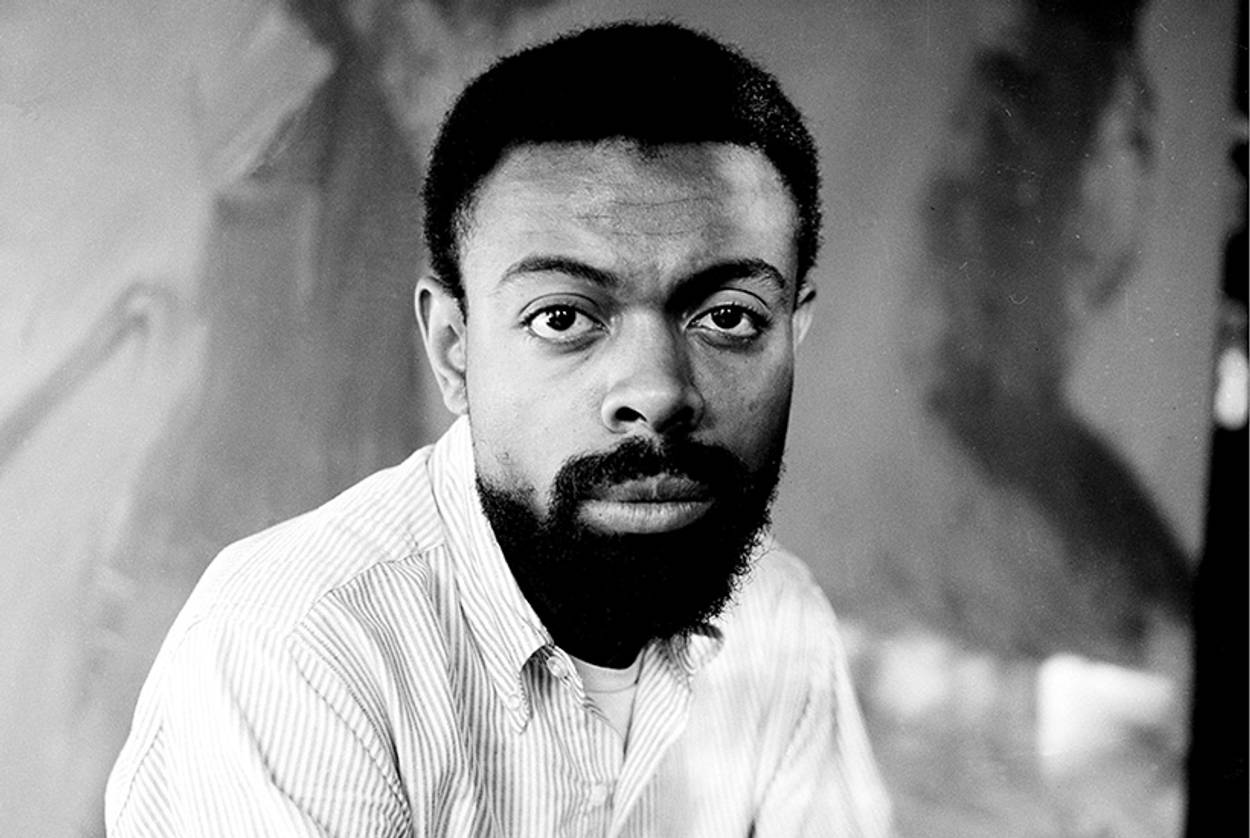

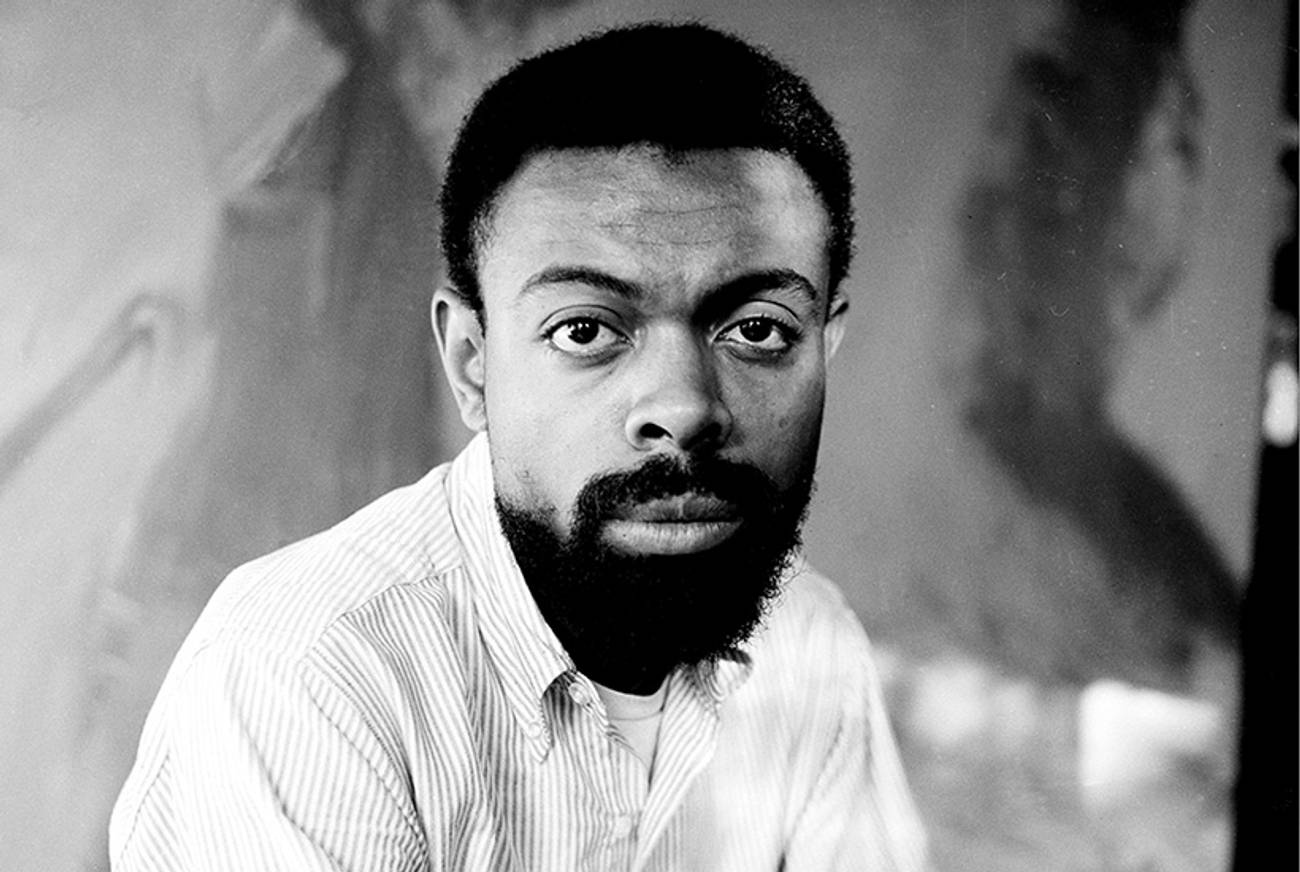

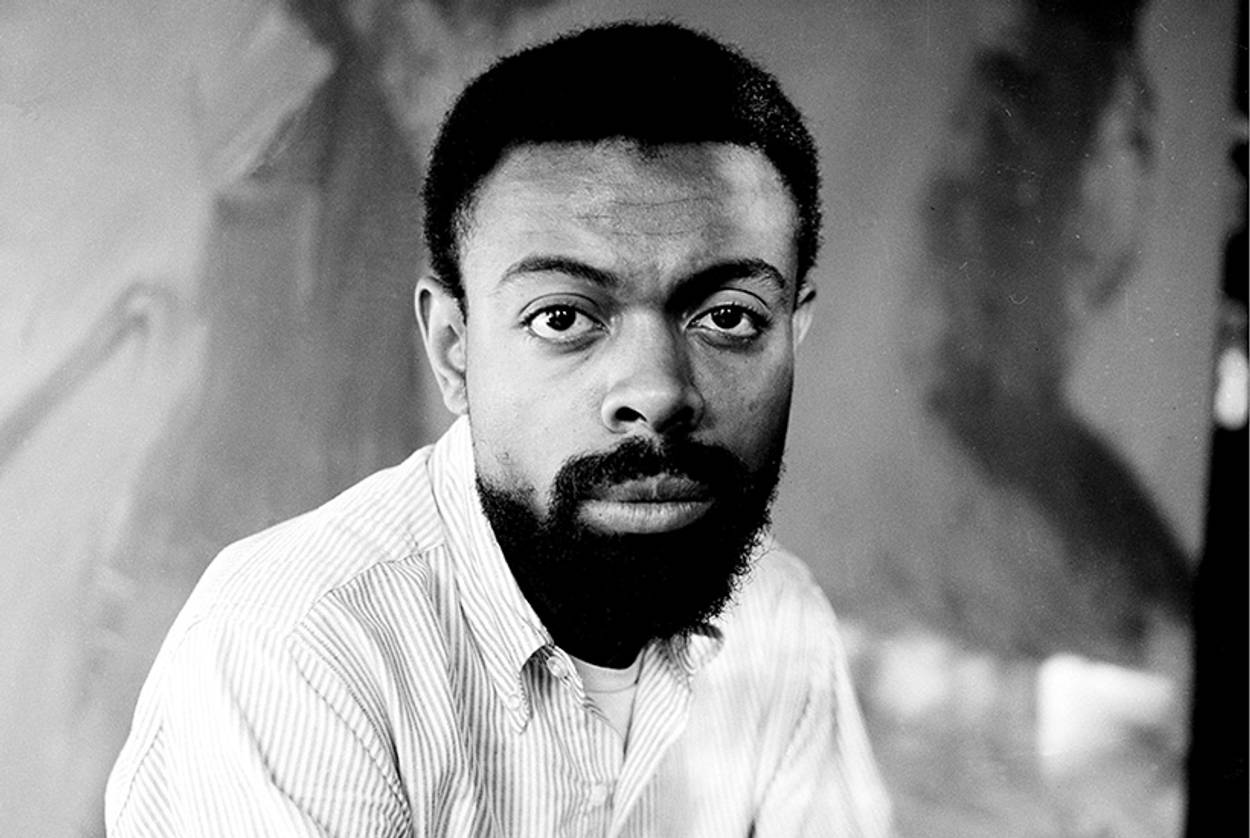

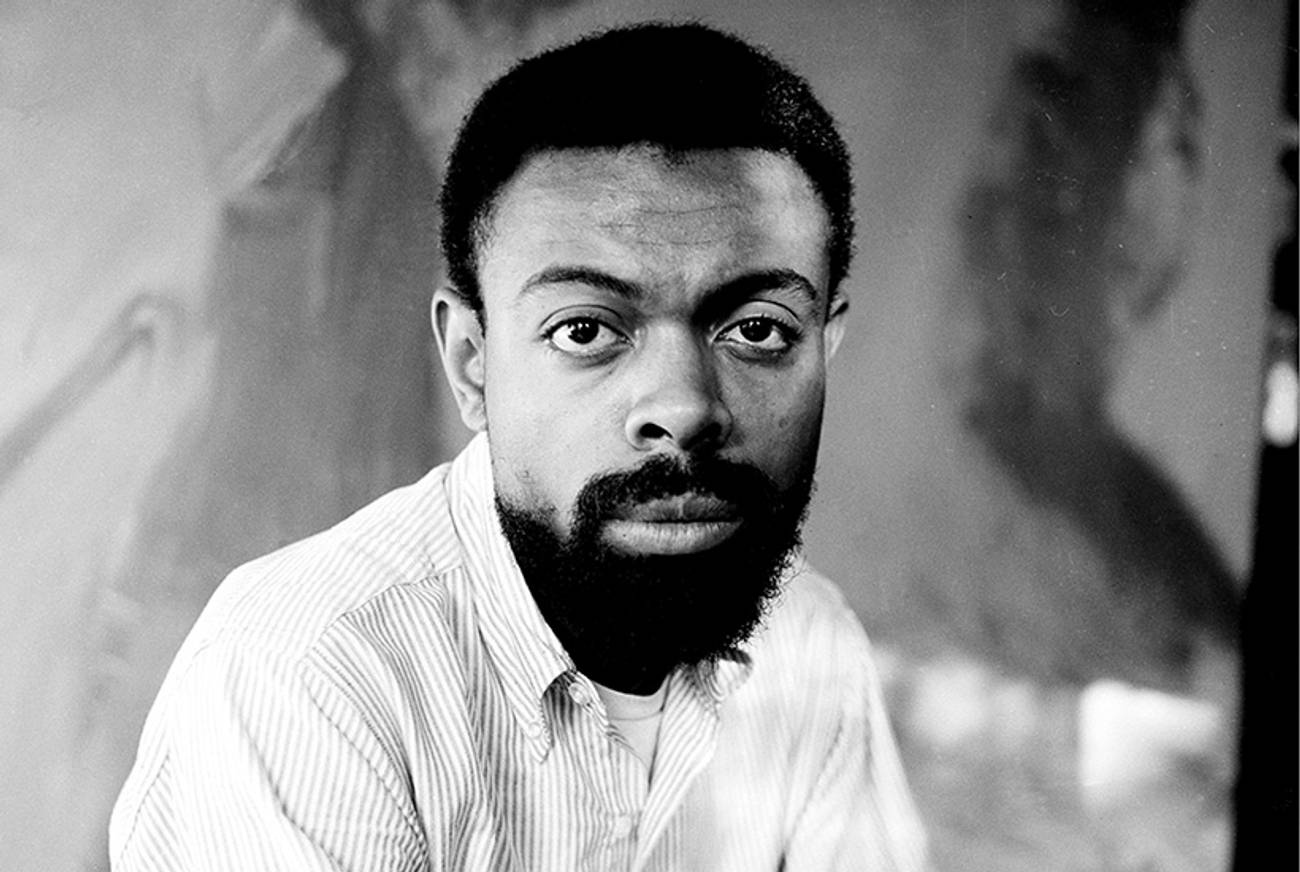

My Favorite Anti-Semite: How Amiri Baraka Inspired Me

Kaddish for the recently deceased poet with a history of bigotry, from a poet with a feeling for jazz

We recognize life’s formative moments long after they’ve occurred, retrospectively. But one spring evening, nearly six years ago, I knew I was in the midst of something major, a turnaround point. At the hushed Stone, John Zorn’s dimly lit East Village club of experimental music, along with three dozen other listeners, I sat staring at the empty lectern with an intensity reserved only for vacant spaces—fraught with a vision, or disappearance, or about to be filled with presence you have obsessively dreamt about. I distinctly remember thinking: Maybe this is what it was like at the Jerusalem Temple, two millennia back, where pilgrims’ eyes searched out the invisible source of the ecstasy they had come looking for. My ecstasy though, was laced with uneasiness.

And then Amiri Baraka came out.

Baraka, who died last week at the age of 79, back then, at the Stone, was not merely a poet, or critic, or activist, but a mythic, mysterious force.

Like many others I first learned of Baraka’s work in 2001, not long after Sept. 11, when his “Somebody Blew Up America” made him America’s most controversial and reviled poet. The anger that filled me, reading Baraka’s allegation that the Israeli citizens were warned of the Sept. 11 attacks in advance, was tinged with bewilderment. “Who told 4,000 Israeli workers at the Twin Towers/ to stay away from home that day” ran the notorious line. The poem, as a whole, depicted a frenzied attempt to identify “the Devil on the real side” as it unraveled a hypnotic tornado of questions: “Who got fat from plantations/ Who genocided Indians …/ Who killed Malcolm, Kennedy & his Brother … Who put the Jews in ovens,/ And who helped them do it.” The meltdown over the questions on the nature of evil is legitimate, necessary, but what was the cheap, unrealistic conspiracy theory doing in the middle of it all?

What, however, vaguely occurred to me then as well was that the measure of the feeling—negative as it was—was bigger than anything I have ever felt toward any poem I had yet read.

Osip Mandelstam, the Jewish Soviet poet murdered by Stalin’s government, wrote of the USSR with noir pride: “Poetry is respected only in this country—people kill for it. There’s no place where more people are killed for it.” Having grown up in the Soviet and freshly post-Soviet Ukraine, I knew how true Mandelstam’s words were. In America, much of the poetry I encountered was light, elegant entertainment. The token New Yorker poems went well with their cartoons—and aimed for a similar affect. Baraka, it occurred to me, came as close to Mandelstam’s dictum as one can get in contemporary America—for a “career” poet, “Somebody Blew Up America” would have been professional suicide.

I was in my early 20s and was exploring the world of poetry and all that went with it—experimentation, spirituality, rebellion, performance—and found myself encountering Baraka’s work again and again. I was interested in the kind of writing that lived off the page and was given life and voice. I sought out words imbued with the sense of improvisation, medium-like channeling, mad prophetic ranting. I felt that in jazz—in the widest sense of that term—there lived a mysterious key to self-understanding. Each of these pursuits and concerns led me to Baraka and, at first reluctantly, I found myself reading through collections of not only his poetry but prose, award-winning plays, music criticism, letters—anything I could get my hands on. Even though I had no interest in politics of any kind, I have never encountered a poet whose work electrified and enlightened me more than his. In a piece called “Tone Poem” he writes:

… All the poems

are full of it. Shit and hope, and history. Read this line

young colored or white and know I felt the twist of dividing

memory. Blood spoiled in the air, caked and anonymous. Arms opening,

opened last night, we sat up howling and kissing. Men who loved

each other. Will that be understood? That we could, and still

move under cold nights with clenched fists. Swing these losers

by the tail. Got drunk then high, then sick, then quiet. But thinking

(and of you lovely shorties sit in libraries seeking such ideas out).

I’m here now, LeRoi, who tried to say something long for you. Keep it.

Forget me, or what I say, but not the tone, and exit image.

The concept of poetry presented here is not a momentary distraction; neither is it some self-glorifying ego trip, but a combustion of unsavory and sacred, visceral imagery against an apocalyptic backdrop, charged with immediacy, and this immediacy’s historical repercussions. Baraka’s closest friend and associate of his Greenwich Village days, Diane di Prima, wrote in her memoir that eventually every artist has to face a choice: “Art as magick, or art as entertainment.” Although Baraka is the only poet in the world whose performance style has earned him comparisons to James Brown, Baraka’s work, at all times, had little to do with entertainment but instead with what di Prima has called “magick.” The magick is felt most palpably in his recognizable tone, shaped largely by his encounters with music. As he put it in one interview:

Poetry is a form of music, an early form of music. … Poetry is the first music. I think poetry predicts music and I don’t think you can disconnect poetry from music.— I think when poetry gets away from music, as is the case of academic poetry, it tends to be anti-musical, having more and more to do with rhetoric than it has with music. The more poetry gets disconnected from music, the less interesting it is and the less likely it is to live as poetry.

The sort of music he loved and wrote about most extensively was jazz—the wild, free, all-revealing communication at the level unavailable to word-slingers. As I, too, listened to the music he spoke of, I knew precisely what the poet meant when he quipped: “If you can hear, this music will make you think of a lot of weird and wonderful things. You might even become one of them.” And, in the liner notes of 1964’s Coltrane Live at Birdland, “In this tiny America where the most delirious happiness can only be caused by the dollar, a man continues to make daring reference to some other kind of thought. … Beautiful has nothing to do with it, but it is.” This was the first time I have seen art criticism that was on par with the art itself: in this case, the undone, wailing spiritual crisis I too heard in Coltrane works—the undercurrent of which drew me to jazz in the first place. Baraka’s stance against life’s trajectory as outlined in the poem “To a Publisher … cut out,” resonated with my own search for meaning and direction, specifically as a poet:

Grandeur in boldness. Big and stupid as the wind.

But so lovely. Who’s to understand that kind of con?

As if each day, after breakfast, someone asked you,

“What do you want to be when grow up??” &

Day in, Day out, you just kept belching.

Like Baraka, I wanted to have another answer to that big question.

Having come into prominence in the late 1950s, known then as Leroi Jones, he wrote in a circle of poets who mattered the most to me, the Beats—Allen Ginsberg, Diane di Prima, David Meltzer, and numerous others. He was then married to a Jewish woman, Hettie Jones (née Cohen), and the couple’s Greenwich Village apartment became the nexus where the revolutionary American poetry was written. In 1965, following Malcolm X’s assassination, Baraka (still as Jones) divorced Hettie—on ideological grounds, later pronouncing: “How could someone be married to the enemy?” He moved to Harlem to become the founding member of what came to be known as the Black Arts movement, the expression of African American art, imbued with radical politics of liberation.

It was during that period that he wrote poems with undeniably anti-Semitic content.

From my early teenage years, I’ve learned to glide past the casually vile anti-Semitism of my favorite writers—Dostoyevsky, Gogol, and Turgenev. But Baraka’s anti-Semitism stuck in my throat. How could it possibly fit in the mind of a contemporary leftist American thinker of dazzling intellect? And why? In the year immediately preceding his move to Harlem Baraka recorded his poem “Black Dada Nihilismus” with the New York Art Quartet. Among the poem’s collage of disjunctive, surreal radicalism and violent imagery, the following lines appeared:

ugly silent deaths of jews under

the surgeon’s knife. (To awake on

69th street with money and a hip

nose.

The issue here is with the unsavory cultural stereotype. Then, one may notice the trademark bracket that never closes and instead turns the reader’s field of attention toward a certain equation, which, if described by a Jewish poet would hardly make one wince. We’re seeing a not entirely foreign set of ingredients: death, Jews, America, assimilation. But coming from an African American activist, the poem implies that the Jewish variety of assimilation in America was warranted, in no small part, by the color of a Jews’ skin. To Baraka, the “hip nose” didn’t merely symbolize becoming less Jewish—but more white. And wasn’t it true that all too many times, in the traditional Jewish circles I have found myself hearing a sentiment Baraka may have been responding to so abrasively: “we pulled ourselves by our bootstraps … they had a chance to do the same, didn’t they?”

In his 1980s article “Confessions of a Former Anti-Semite,” Baraka reflected that back in the 1960s a lot of his resentment had to do with “these Jewish intellectuals [who] have been able to pass over the into the Promised Land of American privilege,” yet whose focus remained on history of their own oppression rather than a true struggle for the equality of all.

And so, not long after “Black Dada Nihilismus,” came other, more painful poems and references. When in 1965, a rupture tore through America’s Left, African American activists came to think that the only way toward equality and self-determination was through militant radicalization. For Baraka, this resulted in his break with Greenwich Village circles. A scholar of the Black Arts movement, James Smethurst, points out that the “particular vitriol of Baraka’s anti-Semitism … is often attributed largely to an inner psychodrama in which he tried to break off from his close emotional ties to individual Jews in downtown bohemia, most intensely his wife, Hettie Jones.”

Smethurt’s idea seems plausible, even appealing, to me. Some 16 years ago, not long after my move to the United States from Ukraine, I found myself developing an acute, embarrassing distaste for my fellow Russian Jews. I caught myself changing seats on the subway to avoid hearing the language of my past. Like Baraka, I too, changed my name, to further enforce the cultural transition that to me seemed only possible through purging, escape, self-disdain. I know something about the costs of these transitions. The poet pushed himself violently away from his closest friends, and maybe in a way I understood that violence even as I found his expression of it reprehensible.

Though he parted ways with the Beats, Baraka continued their tradition of searing confessional poetry. Allen Ginsberg’s confessions were of a sexual, spiritual, and psychological nature; but Baraka’s were those of internal socio-political reality, honest to the point of self-condemnation.

It is important to distinguish among justifications, whitewashing, and the attempt to live, opening oneself to the complexity of history and human nature, in all of its beauty and violence, ugliness and hope. Baraka’s hatred was not something that warranted excuses, or even attempts “to understand” or discard for the sake of his other writings. His complex personae fed into one another. As writer and cultural critic Greg Tate wrote, “Baraka’s literary forms are so rich and provocative because of his personality, not in spite of it. As could also be said of hip-hop MCs, Baraka’s best art puts a premium on projecting his bad attitude.”

That spring evening, at the Stone, I finally saw Baraka, face-to-face. He was short and frail, nerdy in a hip sort of a way, elegantly dressed, and, I remember thinking, he looked like an African American grandmother. The mount of tension I felt in expectation of the encounter lifted—though no epiphanies or resolutions came. I beheld him and enjoyed the set immensely and laughed and clapped along with other, predominantly white, people in the audience. I allowed myself the experience of living inside the acute conflict—and isn’t that what poetry is made of?

Baraka, in all of his complexity, tried to live, and channel intensity, revelation, victories, and failures that among his best readers will bring the desire to respond, think deeply, to dread and to be awed. As poet and scholar Ammiel Alcalay said, introducing Baraka at one of the poet’s last public appearances: “He has constantly exposed himself and his ideas to public scrutiny, even attack, opening a window into participation in the amalgamation of selves and ideas that form the creative, political subject. Amiri’s example has served as a constant reminder that such selves, ideas, forms, even communities, are won through struggle and confrontation with oneself and the world.”

What Baraka has written, in the liner notes to John Coltrane’s album, about our country may just be equally true about himself: “One of the most baffling things about America is that despite its essentially vile profile, so much beauty continues to exist here. Perhaps it’s as so many thinkers have said, that it is because of the vileness, or call it adversity, that such beauty does exist. (As balance?)”

Rest in peace. Peace in unrest.

Jake Marmer is Tablet’s poetry critic. He is the author of Cosmic Diaspora (2020), The Neighbor Out of Sound (2018) and Jazz Talmud (2012). He has also released two jazz-klezmer-poetry records: Purple Tentacles of Thought and Desire (2020, with Cosmic Diaspora Trio), and Hermeneutic Stomp (2013).