An Enemy of the People

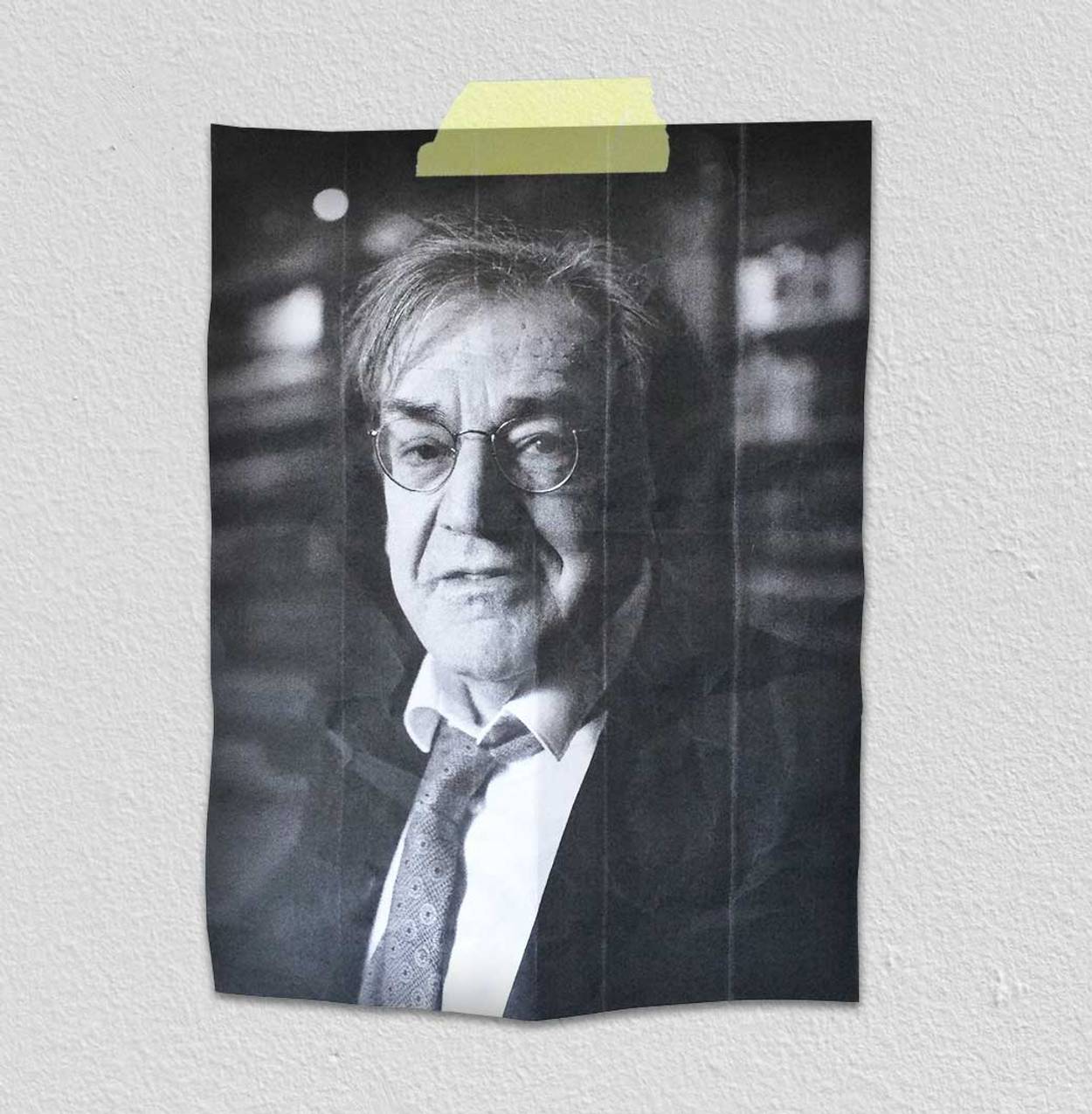

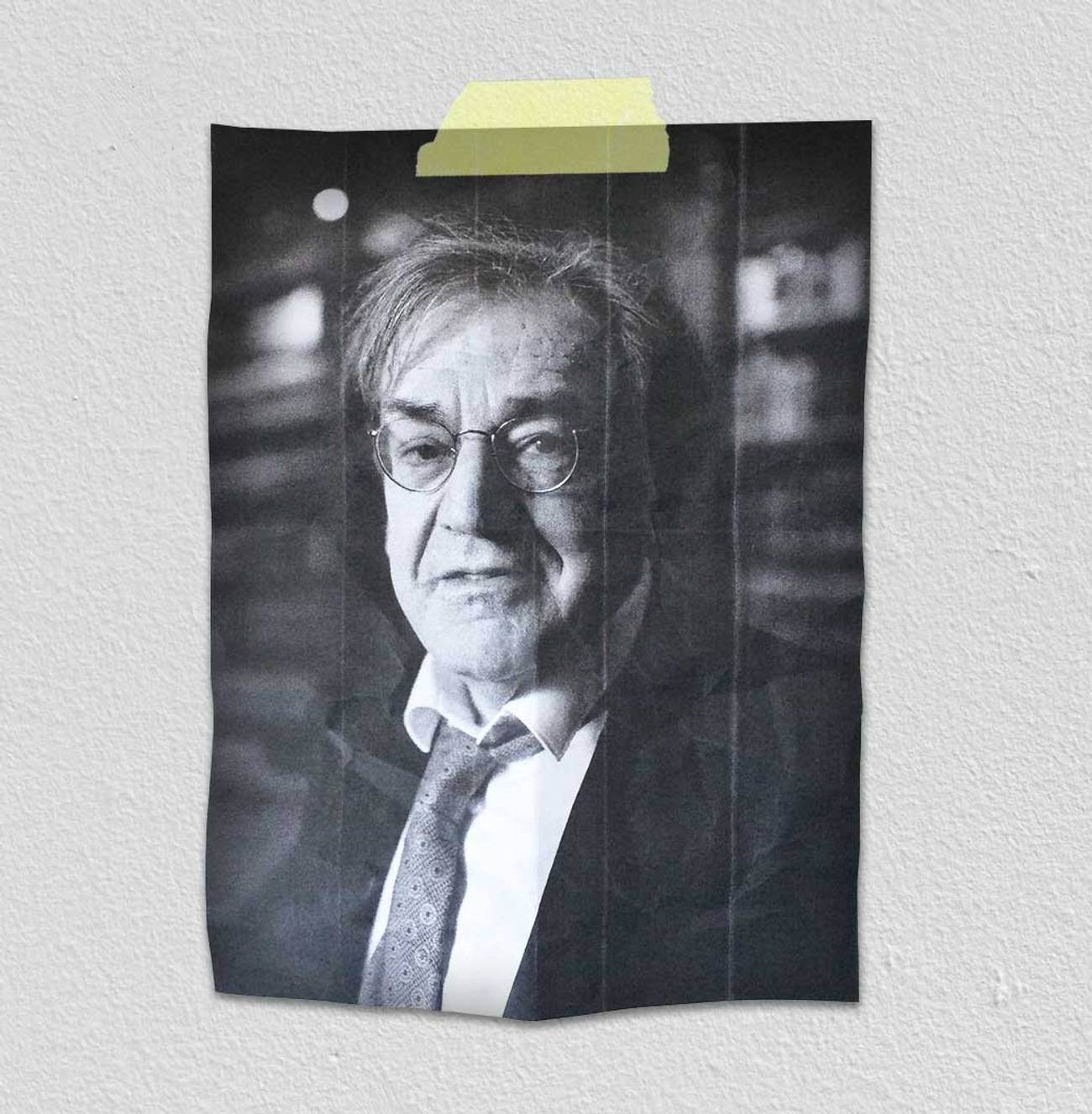

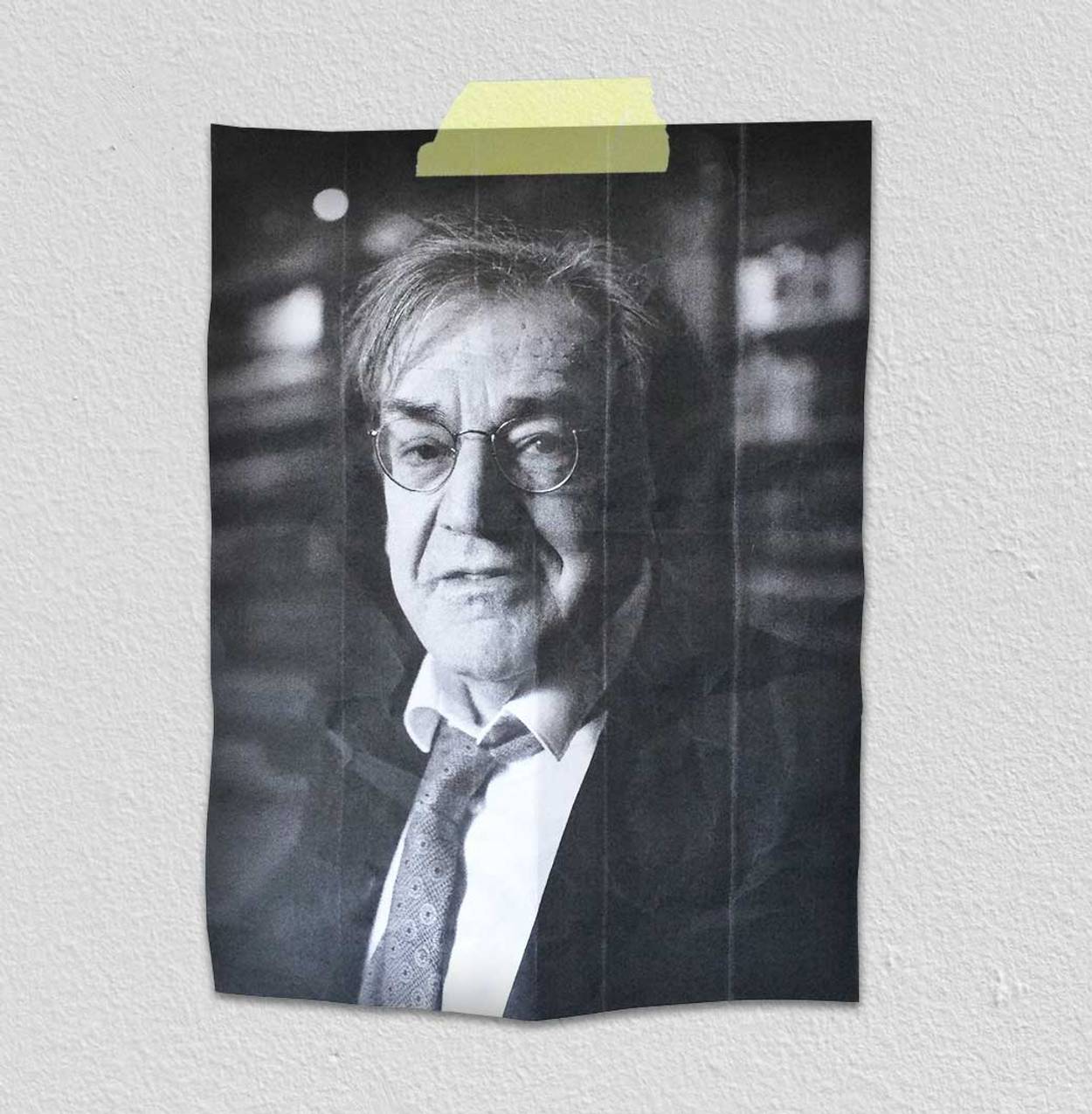

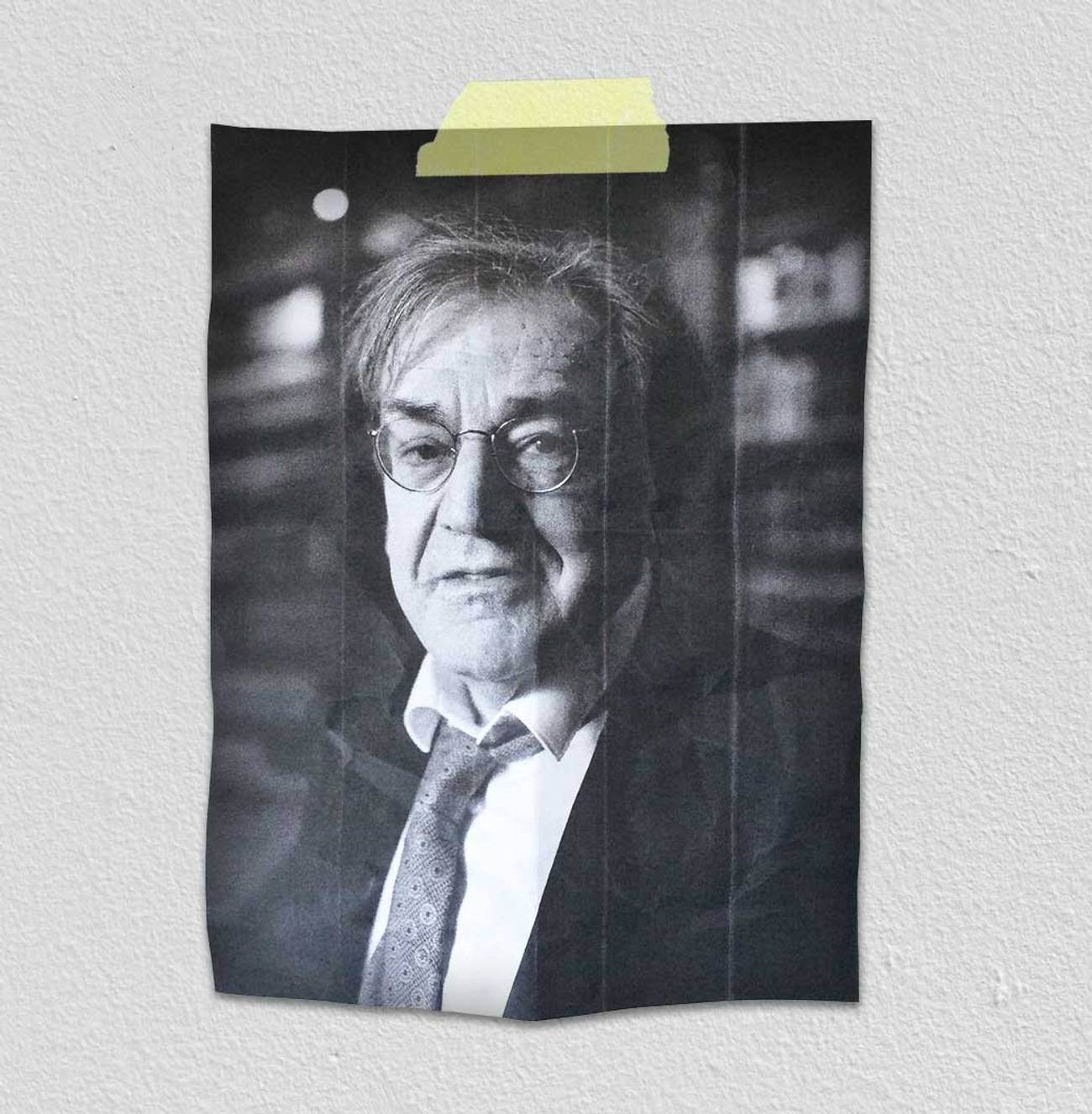

Finkielkraut, attacked (and defended)

The Yellow Vest sidewalk mini-riot against Alain Finkielkraut, the French philosopher, in Paris a few weeks ago—widely and even internationally reported in the press and visible here—deserves an additional commentary, apart from the obvious remark made by many people at the time, to wit, that manias against the Jews have gotten out of hand in France. Finkielkraut was walking in the street, when a group of Yellow Vests discovered him, and, recognizing his face, famous from a thousand talk-show appearances, shouted at him, “France belongs to us! Damn racist! You are a hatemonger. You are going to die. You are going to hell. God will punish you. The people will punish you. Damn Zionist!,”—along with “Go back to Tel Aviv!,” “Get lost, dirty Zionist shit!,” “We are the people!,” and other such cries, expressed with an air of violent menace—until he was rescued by a more sympathetic Yellow Vest and by the police.

Somebody filmed the encounter. The Yellow Vests looked bad. In reality, Finkielkraut was born in France (of parents who had fled Poland) and was naturalized at the age of 1. His writings have always struck a French patriotic note, even in the years before he adopted patriotism as a theme. His initial response to the Yellow Vest movement was approval. He has written cleverly and at length about Jewish identity in France and about the anti-Jewish fervors, but those are French topics, and not Israeli ones. Toward Israel, he has always adopted a double posture: warmly supportive of the country and its right to exist, sharply critical of the West Bank settlements and the politics of Benjamin Netanyahu. And Israel has never been his major obsession.

The sidewalk attack ought to remind us, in short, that Zola’s phrase (in his immortal J’accuse) was “imbecile anti-Semitism,” and not something adjective-free. Imbecility undergirds the phenomenon. If the attack on Finkielkraut revealed anything new, it was only by showing that imbecilities of different provenances can blend together—a loathing of the Jews compatible with the leftist tone of Yellow Vest economic protest; a loathing in the populist mode, with its rhetoric of “the people” against the Jews; and, as it happens, a touch of Islamist loathing, to boot. The most vituperative of the Yellow Vests shouting at Finkielkraut turned out to be an Islamist, known to the French police. The Yellow Vests on the sidewalk must have found the combination very exciting.

But incidents like this also reflect a second popular impulse, parallel to a mania against the Jews, but different, and worthy of its own commentary. This is a suspicion of the intellectual elite, conceived in melodramatic terms. It is the worried suspicion that, beneath their benign and respectable appearance, the grandest and most impressive of philosophers and writers may be harboring the darkest of reactionary thoughts and theories, intended to roll back the cause of human progress. And it is the idea that we, the vulnerable potential victims of the dangerous thoughts, ought to conduct an investigation, perhaps by looking into anything the suspect intellectuals may have written, in search of incriminating passages. Or we ought to rummage through their offhand remarks, given that books are opaque, and mutterings are transparent. And shouldn’t a popular tribunal be convened?

The popular tribunals do convene, as everyone has noticed. The prosecutors rise from their seats. The American universities have become famous for those melodramatic scenes, with crowds of undergraduates convincing themselves that Satan or Joseph de Maistre is about to deliver a lecture, and must be stopped. But student fads are the least of it. In our era, the loftiest of intellectual journals have been known to execute their own editors at noon. If the French version of this sort of thing is different, it is chiefly because the best-known of writers, and not just the academics, can find themselves on trial now and then, not just in the “court of public opinion,” and not just in the American closed-door Title IX university hearings (which is bad enough), but in courts of law.

This has been Michel Houellebecq’s situation, brought up on charges in France some years ago for having insulted Islam, which, of course, he had done—Houellebecq, whose novel Submission, is routinely denounced as racist (though an exposé of anti-Semitism is one of its principal themes). Pascal Bruckner was obliged more recently to defend himself in court, not once but twice, because of his analytic dissections of the Islamist controversies in France—Bruckner, the author of An Imaginary Racism, whose crime can be guessed at from the title of his book. Georges Bensoussan, the historian of the Jews in the Arab countries (in a compendious 900 pages), was brought up on charges for having said in a radio interview that, among Arab families in France, “anti-Semitism is imbibed with one’s mother’s milk”—though, like Houellebecq and Bruckner, Bensoussan managed to avoid conviction (in his case because he had quoted someone else, and the court ruled that he had merely misspoken, and his intentions were not criminal).

And there is Finkielkraut. In 2005, Finkielkraut found himself under a legal accusation for having pointed out, in an interview with Haaretz, how large and significant was the Muslim and African component in the French riots of that year. Finkielkraut, too, got away undamaged, which, in regard to the well-known writers, does seem to be the rule. But there is no avoiding the reality that court cases, one after another of them, reinforce the idea that intellectual life stands at the border of the impermissible, and literature is the neighbor of crime, and surely some of these writers must, in fact, be enemies of the people, and ought to be punished. Only, what should their punishment be? Oh, and look, here comes a well-known writer, ambling down the sidewalk!

Finkielkraut has had to deal with this sort of thing repeatedly. He used to live in the Paris suburbs, but discovered that harassments on the commuter train were making life a misery, and he moved to central Paris. Three years ago, he went to take a look at a young people’s left-wing protest in Paris, the “Nuit debout” occupation of the Place de la République, and the protesters expelled him with a degree of vituperative nastiness (“one of the most notorious spokesmen of violent identity racism,” said one of the leaders) that made the newspapers. The verbal assault on him last month was anything but exceptional, then. The man has been designated a menace to the human race too many times over the years; and the idiots in the street treat him accordingly.

What purpose is served in speaking about someone as thoughtful and flexible as Finkielkraut in one-syllable ideological terms, left and right?

Then, too, an echo of the melodramatic suspicion appears from time to time in the respectable and mainstream press, where extreme or crazy-sounding accusations might seem in bad taste, but where, even so, it is sometimes assumed that a gigantic ideological battle between progressives and reactionaries comprises the ultimate reality of the intellectual world. And, under those circumstances, surely it is necessary, in the name of lucidity and reality, to paste a single all-revealing ideological syllable, left or right, across the forehead of every well-known thinker who addresses political topics even on rare occasion. About Alain Finkielkraut, then, who addresses political topics night and day, everyone’s first and only query appears to be: Which syllable should it be?—as if, in coming up with the label, we would know what to make of his ideas, and maybe could spare ourselves the trouble of reading his books.

Finkielkraut himself has emphasized or perhaps boasted that, like other people in his generation, he started out as a student insurrectionary in the uprisings of 1968. And he spent the next few years as a militant of the Marxist cause, in the faintly anarchist version known as “autonomist.” He was a schoolteacher who believed in dismantling the authority of schoolteachers. He sang “Bella Ciao.” He was a classic man of the ’68er left, on its hipper side. He was also alive to his own era, and, in the 1980s, he began to lend his support to the dissident movement in the old Soviet bloc. He studied the writings of Czesław Miłosz. A combination of anti-totalitarianism and veneration for high culture became his updated cause, which meant that already he was in trouble with a certain part of the left.

He distinguished himself in defending the victims of Serbian nationalism in the Balkans. He was a champion of Croats and Muslims. I think it fair to say that he was one of the people who inspired the French military intervention in the Balkans, which brought about, after a while, the American intervention. Then he turned back to the problems of his own country and the consequences of the North African immigration. And his detractors on the left, apoplectic by now, began to accuse him of having veered not just to the right, but to the remotest shores of the right-wing extreme, which, in France, means blood-and-soil opposition to the French Revolution, in the style of the royalists of the 1890s—a ridiculous accusation, which might almost seem funny, except that people do say these things.

You can see the charges against him in English in a book from last year called The End of the French Intellectual, by an Israeli leftist (with Parisian credentials) named Shlomo Sand—who, in lighting into Finkielkraut, restrained himself only by remarking, “True, this is not yet fascism.” And restraint is not for everybody. Alain Badiou, the last of the Maoist philosophers, has accused Finkielkraut of having adopted neo-Nazi views, no less—this, about someone who grew up gazing at the numbers tattooed on his father’s forearm. Or, less aggressively, it is said that, instead of having veered into old-fashioned reaction, Finkielkraut has evolved into a new-style “reac.”

Or, more conventionally and plausibly, it is said that, yes, he does appear to have drifted rightward over the years, though only into zones that ought to be described as “conservative,” where he can be politely designated as “well to the right,” or some such phrase, with emphasis on the “well.” But even the temperate descriptions come down to affirming that, in one way or another, the man of the admirable left has metamorphosed into a man of the appalling right—which, in France, can be a fairly devastating thing to say about a writer or intellectual, with a guarantee of an exodus of friends and a good probability (as the late André Glucksmann recounted in his autobiography) of a rude reception among the anonymous passers-by on the street.

I have to wonder, though, what purpose is served in speaking about someone as thoughtful and flexible as Finkielkraut in one-syllable ideological terms, left and right? He is a writer on a hundred themes—on politics, French history, the erotic, male-female relations in French literature, the ironies of Milan Kundera, the plotlines of Philip Roth, and so on—which not even the most tedious of dogmatists could boil down to a slogan or a hand signal; and no one has accused Finkielkraut of dogmatic tedium. Anyway, he has explained more than once that, if he had, in fact, become a man of the right, he would be happy to say so. But he does not say so, and this is not merely because, on one political issue or another, he advocates positions that fit more comfortably on the left in France—e.g., support for secularism, as against the traditional demands of the Catholic right; and his enthusiasm for public education.

He instructs us on philosophical grounds that social wrongs are rooted in history, and not merely in the immutable nature of man, and can therefore be redressed, at least sometimes—which puts him once again elsewhere than on the right. He has explained that, in regard to the French Revolution—which is, after all, the ultimate reference point for definitions of left and right—he does not, in fact, yearn to roll it back. He prefers the company of Jules Michelet, the Revolution’s most sympathetic historian, over that of Edmund Burke, the Revolution’s sharpest critic. But mostly he objects to the whole idea of dividing the universe into left and right, which is the lesson that he learned from Miłosz. He looks upon left-right divisions as a formula for each side to dream of crushing the other, which means a formula for tyranny.

President Emmanuel Macron defended Finkielkraut against the sidewalk rioters (which was generous on his part, given some of Finkielkraut’s remarks about Macron), by describing him as a “man of letters,” and this makes more sense. Letters, and not doctrines, are his natural home. I wonder if there is a better essayist anywhere in the world, when it comes to explicating the quirks and meanings of complicated ideas. I have never understood why he is not better known in the English-speaking world. The modern French essay style favors a tone of brusqueness and agitation (not to mention a style in certain quarters, now somewhat passé, favoring the higher gibberish), but Finkielkraut’s inspiration has always pointed in a smoother and more pleasing direction.

He may have a rough time of it on the commuter train or the sidewalk, and yet, when he is at last safe and sound at his writing desk, he manages almost always to be elegantly serene and, in the classic French manner, tranquilly rhythmic. His schoolboy exercises in translating Cicero and Virgil have evidently stayed with him. I think his earlier books were perhaps the most elegant of all, in their lucidity and dazzle, and his more recent books less so, by a shade. But nearly everything he has written, recently or long ago—everything that I have read—reflects the same prose discipline and personal charm, quite as if, over the years and despite what people say, he has not really changed at all.

The denunciations that come his way do have to have an origin, though, and I think I can identify the when and the where. It was in one of his earliest discussions, back in the early 1980s, on a topic that might appear to be the last word in dusty arcana. This was the Dreyfus Affair, from 1894 to 1906, an ancient dispute. But, as he showed, the core of the dispute was a philosophical quarrel, and the philosophical quarrel has remained entirely alive and unresolved, even if, at the end of those dozen years, the supreme court in France had its say, and Captain Dreyfus was officially declared innocent.

The quarrel was over how to judge evidence. The evidence against Dreyfus—he was accused by the French army high command of spying for Germany—revealed, to anyone who examined it closely enough and applied the laws of logic, that he had been framed. But there were different theories about how closely the evidence should be examined, and from what angle, and how rigorous should be the logic—three main theories, each of which has proved to be an enduring impulse for one another sector of modern opinion. And there was a fourth theory, which Finkielkraut has more or less adopted as his own.

The right-wing theory dismissed evidence on principle, in the belief that truth is best revealed by consulting the emotions, and not by dwelling over the aridities of fact and logic. The appropriate emotions from the right-wing perspective were these: a love of France, which the right-wingers pictured as the French race and the French soil; a love of the army and its high command, pictured as the defenders of the race and the soil; a disdain or loathing for Jews like Dreyfus, pictured as a different race, without ties to the soil; and a disdain for the abstract thinking that fails to reflect the realities of blood and soil. And, since the army high command said that Dreyfus was guilty, anyone with the appropriate emotions could only agree that he was guilty.

A second theory belonged to the orthodox Marxists, beginning with Karl Marx’s friend and comrade Wilhelm Liebknecht, no less, who regarded themselves as champions of the oppressed. The champions of the oppressed clung to an identity-politics notion of truth. They observed that Captain Dreyfus was a bourgeois, which meant that he could not possibly be oppressed, which meant that he might very well be guilty. And, in any case, the fate of a bourgeois was no concern of theirs, and there was no point in troubling over the evidence. Nor was anti-Semitism a Marxist concern, since it did not bear on the ultimate source of oppression, which can only be capitalist exploitation.

A third theory belonged to the more-or-less liberal left, which meant Zola and his intellectual friends. Those people regarded themselves as the champions of science, and therefore were keen on examining evidence and logic, without reference to blood, soil, the nation, the proletariat, or anything else. Evidence and logic led them to conclude that Dreyfus had indeed been framed. And they observed that anti-Semitic prejudices were an irrational folly, unacceptable from a scientific standpoint.

The fourth theory, though—the idea that transfixed Finkielkraut, that changed him for life, that animates a good half of his writings—was a lonely one, which hardly anybody would remember today, if Finkielkraut had not made a fuss over it. Its champion was Charles Péguy, the Catholic poet, who was a man of the left, though in a fashion all his own. Péguy recognized that Dreyfus was innocent. But he did not approve of the dry rationalism and cerebral style of the liberal left and the intellectuals. He saw something to admire in the right-wing cult of the emotions. It was just that, in his view, the right-wingers invoked their emotions incorrectly. The right-wingers reduced human considerations to questions of race and soil, which are material considerations, and this was a mistake.

Péguy explained that man is material and spiritual both, with the two qualities intermingled. To love only what is material is to fail to appreciate what is human. He shared with the right-wingers a love of France. But he thought of France, too, as material and spiritual both. In his view, the spiritual qualities of France—its mystique—arose from the entire history of the country, beginning with the kings and reaching a grand culmination in the French Revolution, with its principle of human rights and its aspiration for universal justice, which are the spiritual glories of the French republic. The glories in question, as applied to Captain Dreyfus, left no doubt as to his innocence. And the glories left no doubt that every good republican in France needed to defend the wronged and martyred victim; and, in sum, a patriotic love of France made Péguy a Dreyfusard.

He also sympathized with the Jews as a whole, and this was unusual. He knew that, during the dozen years of the Affair, the wave of hatred for the Jews in France was intense, and Jews of all economic classes, and especially the lower class, went through terrible experiences—lives and fortunes destroyed, careers ruined. He noted that, in Russia, too, the Jews were undergoing dreadful times, expelled from certain regions, singled out by law for special discrimination. And in other countries: Romania, Hungary, Turkey, Algeria, and America. The Jews were persecuted in the name of Christianity, and persecuted in the name of Islam. He saw it all. Nor was it just a matter of his own moment.

He wrote: “I know this people well. There is not a spot on their skin that is not painful, where there is not an old bruise, an old contusion, a deaf pain, the memory of a deaf pain, a scar, a wound, a bruise from the East or the West.” He also noted that, in the eyes of the anti-Semites, Jews were powerful people who controlled the destiny of the world; and this belief made it impossible for a great many people to see the scars and the wounds. The Jewish suffering was wide and ancient and deep; and it was invisible. The sufferings of the Jewish lower class were doubly or perhaps triply invisible—doubly invisible because the lower class Jews were more vulnerable to persecution than everybody else, and triply invisible because, in the imagination of the anti-Semites, Jews were rich, and the Jewish poor did not exist. But the Jewish poor existed.

Then again, he noted that, in spite of every terrible thing, the Jews displayed a quality of spiritual grandeur, a spirit of sympathy for other people, a spirit of solidarity. He noted among them the persistent vocation of the ancient Hebrew prophets—not among everyone, of course, and not among the official Jewish leaders, who had been beaten into submission by their oppressors: the Jewish leaders who, crouching in fear, wanted nothing to do with Captain Dreyfus and his troubles. But the prophetic vocation remained alive, even so, embodied by one person or another—embodied by his own friend, the anarchist Bernard Lazare, a principal hero of the Dreyfusard cause, perhaps the greatest hero of all—whose virtues were recognized by every Jewish peddler on the street. The Jews were the “prophetic race.” And the spectacle of their spiritual grandeur filled him with more than admiration—filled him with love, and gratitude, and awe.

Somebody should put together an all-inclusive anthology of writings on warmly pro-Jewish themes by major non-Jewish literary figures. It would not be a massive volume. Péguy’s scattered pages on the Jews in his memoir of the Dreyfus Affair, Our Youth, from 1910, would occupy half the book. In any case, the young Alain Finkielkraut was smitten with Péguy, which is easy to understand. He set out to mount a Péguy revival, and the revival became for him a lifelong project. Then, too, Finkielkraut began to adapt and update a few of Péguy’s thoughts for purposes of his own, and, in doing this, he came up with main points of his own originality, which I would describe as patriotically French, indignantly Jewish, instinctively rebellious and (Péguy would say) prophetic, in fertile and novel combination.

Finkielkraut’s Péguy revival ran into a complicating circumstance, though, which was a parallel revival of manias against the Jews, something unexpected: an additional story of the 1980s. This was the anti-Semitism of the immigrant Islamists in France. Imams from Algeria made their way to the immigrant suburbs and began to preach the word. And the word turned out to be a classic mania about the Jews, medieval in style, rendered sacred with quotations from the ancient Islamic texts, rendered modern with paranoid inputs from the European ultra-right, and rendered drunk on a fantasy of the coming Day of Judgment, when the Jews will be killed. The suburbs, as it happened, were not just Arab (and Berber), but, in a small way, Jewish, with a population of the lower-class Jews who, even today, are thought not to exist—mostly the immigrant Jews who had fled to France from North Africa in order to escape the Arab revolution, only to discover that, in France, too, an Arab revolution was still pursuing them.

Those people, the Jews in the suburbs, began to experience the kinds of harassment and discomfort that could be expected in neighborhoods where an increasing number of the neighbors believed that, during the last 1,400 years, Jews have been engaged in a diabolical conspiracy to destroy Islam and ought to be massacred. Jewish children began to discover that life in the schoolyard was hell. Their parents discovered that teachers and school principals were overwhelmed by the scale of the problem, and there was no alternative but to remove the children from the public schools. And the Jews began to flee the neighborhoods. Some 60,000 Jews out of a total of 350,000 Jews in the Paris region, according to Finkielkraut’s figures, have decamped from one locale to another in France during the last decade or so, in order to escape the neighborhood persecutions. Or they have decamped to Israel. Finkielkraut himself, in decamping from the suburbs to central Paris, was one of the earliest of those people, though he has not made a point of complaining about it.

Those were not tiny events. And yet, Péguy’s observation about the invisibility of Jewish suffering circa 1900 turned out to be applicable, as well, to Jewish experiences circa 2000. The persecutions expanded, and, for a good many years, they remained invisible to the national journalists in France, the government, the intellectuals, and even to the august notables in the Jewish elite, who, exactly as in the Dreyfus Affair, ought to have known better. The persecutions were visible to Finkielkraut, though, and to Bensoussan, the historian, and a few others. In Finkielkraut’s case, this was largely because his talk show on Jewish radio in France made him a familiar and friendly figure to the Jews in the suburbs, and his listeners reached out to him to share their troubles. By the early years of the new century, he was pretty upset about what he was hearing. And now he found himself confronting a still more peculiar circumstance.

In the world of journalists and intellectuals who consider themselves sophisticated and progressive, in Europe and America both, it has become fashionable to say that France and the European continent as a whole have been undergoing a crisis of racism so deep and frightening as to relive the black years of the 1930s—only, this time with the Muslims cast in the role of the Jews. This is an idea with a curious history. Finkielkraut himself may have been one of its progenitors, back in the early 1990s, in the course of his protests against the persecution and massacres of Muslims in the Balkans.

That was in a period when the Islamist movement in France and other places in Europe was still small and marginal and easily ignored—even if, in France, the terrorist attacks on random Jews had already begun (as early as 1980). But the movement grew with extreme rapidity, with the effect that, among the various European political tendencies that cultivate exterminationist fantasies about other populations, the Islamists ultimately achieved pride of place—though it is all too easy to imagine still other movements, anti-Muslim and equally ghastly, swelling into something still larger, perhaps tomorrow or the day after.

In France, the police statistics have shown for quite a few years that, while the Jews are less than 1 percent of the French population, they are the victims of a very large percentage of violent hate crimes—in 2017, nearly 40 percent of such crimes that were attributed to racial or religious animus, with the assumption being that Arabs and Muslims are largely responsible. And atop the tide of low-level incidents and schoolyard persecutions and the bloodcurdling sermons came a series of shocking public scenes—the sacking of the Jewish stores in suburban Sarcelles, the attacks on synagogues, the left-wing pro-Hamas march in Paris in 2014 that broke into cries of “Death to the Jews!”—followed by the wave of Islamist massacres in Europe, and the wave-within-the wave of terrorist attacks on Jews in France, Belgium, and Holland, no longer as isolated events but as a sustained campaign. Which led the French government to station military patrols, not merely police officers, at the door of every Jewish institution, for a while. Which was followed by a scattering of other murders, which has given the reality a still clearer focus, until finally it has become hard not to suspect that in Europe today the “Jews” are the Jews.

Finkielkraut pointed this out—though he also warned against drawing parallels to the 1930s. And he pointed out that, under an Islamist pressure, an authentically reactionary development was underway in some of the neighborhoods—the rollback, at last, not just of cultural progress in regard to superstitions about Jews, but a larger rollback of secular education, and a rollback of women’s equality, a rollback that enforced a segregation of the sexes and prevented men in workplaces from shaking hands with their women colleagues and limited the opportunities for girls’ education.

But there was not the slightest chance that his message was going to be well-received. A great many intellectuals and journalists remained frozen in a nameless ideology of their own, descended from the orthodox Marxism of the 1890s, which asserted two principles, neither of which was open to criticism or new information. There was a belief that oppression is unitary and not multiple—the unitary oppression that Marxists used to picture as capitalist exploitation, and that leftists of our own era picture as an all-encompassing White-European-versus-Third-World racism. And there was the equally dogmatic belief that, in inquiring into the unitary racist oppression and its consequences, the thing to examine is personal identity, and not empirical evidence.

So Finkielkraut reported racism; but the particular racism he reported did not fit into the category of White-European-versus-Third-World, which made it unrecognizable. He pointed to events. But there was a bias against looking at events. He pointed to certain neighborhoods. But the neighborhoods he pointed to, judged on identity grounds, could not possibly be the home of racist oppressors. And, as a result, a great many intellectuals and journalists and a sizable public could only conclude that, if anyone was a racist, it was Alain Finkielkraut, a man without compassion—just as Bensoussan, the historian of the Arab Jews, was judged to be a racist.

It may be that Finkielkraut has responded less than adroitly to the insults that came his way. He has noted that certain authors on the extreme right have proposed observations about the doleful effects of immigration that he considers valid and well-put, and, in expressing his approval, he has declined, a bit haughtily, to make a big display of his larger disagreements (though he does express disagreements)—which has allowed his detractors to proclaim that here, at last, is proof of his crypto-royalism. I do not think it would have cost him anything to show a bit more warmth toward his non-Islamist Arab neighbors, themselves the first victims of the Islamists. Nor would it have cost him anything to express his solidarity a little more ardently with his intellectual comrades from Muslim backgrounds, the doughty liberals and feminists, heroes of the anti-Islamist cause—though he does express solidarity, in print and on his radio show. Perhaps he has allowed himself to appear chilly.

But he may have reflected that his purpose in these controversies has been to reveal truths and express indignation, and he has not wanted to soften the truths or the indignation under a blanket of reassuring nuances and complexities. Nor has he looked for ways to cheer up his readers by pointing to hopeful indications of a better future. In the course of a study of Péguy from as long ago as 1991, he wondered, “Are we sure that we are right in defining reason as a lack of emotion?” He chose emotion. And, over the years, the emotion he chose has largely been a gloomy one—gloomy about the political left and its systematic blindnesses (an early and enduring theme), gloomy about the state of modern culture (a somewhat later theme), gloomy about the Islamists and their role in the immigration (a recent theme), gloomy about France’s ability to remember and understand its own grandeurs (likewise a recent theme, though with older roots).

Nothing can discourage him from being discouraged—not even his own successes, which are undeniable. He does win his debates sometimes. His gloomy arguments bring him a round of applause. Crowds march in the French streets to condemn the resurgent manias and the violence against the Jews—all of which ought to satisfy and delight him and arouse his own applause. And he does applaud. He savors his victories. He is not inhuman. Grumpiness appears to be a point of principle with him, though, as if in aggressive demonstration of his militant posture—a grumpiness presented in the pure and limpid prose of a man whose own unhappiness will never take away from the happiness of expressing himself. He complains (in his L’identité malheureuse, or Unhappy Identity, from 2013, the most controversial of his recent books) about students in the public schools being disrespectful to their teachers—they squirt ink at the teachers!—as if to show that old-fogeydom does not intimidate him, either; and the flash of old-fogey irritation adds still more snap to his protests.

I have noticed that his friends sometimes try to persuade him to defend himself more deftly, or to temper his vehemence, or to cheer up, if only on tactical grounds. A year and a half ago, he and the philosopher Élisabeth de Fontenay brought out a volume of amicable email exchanges, her complaints about him and his responses, called En terrain miné, or In the Minefield, in which she all but implores him to adopt a lighter tone, as if with her hand on his arm and an earnest look on her face. She bristles at his willingness to speak well of his favorite right-wing authors, and his outrageous (in her eyes) defense of the French arts of gallantry and flirtation, and other transgressions—though she grants that, in the end, she and he are on the same side. She says, “You are courageous, without a doubt, but I often deplore what I would provisionally call your imprudence.” And Finkielkraut, exasperated at her exasperation, chooses to ease up not at all—even while insisting, yet again, that he is not a man of the right.

If I read him correctly, though, he has clung to his style and mood principally out of a sincere and considered adherence to the views on patriotism and civilization that he has discovered in Charles Péguy. He is appalled by something bigger than Islamist bigotries and the trendy fashion for abiding the bigotries, and this is a weakening or decline in French confidence in French civilization itself—the civilization that is coolly rejected by a percentage of the immigrants, and is denounced as the enemy by the Islamists, and is regarded as a criminal enterprise by certain kinds of left-wingers, and is undermined by market economics, and which, in his anguished estimation, has lost its urge to defend itself, abandoned by the addled professors.

He deplores the academic suspicion of the cultural past, the genre studies that reduce the history of literature to a sociological commentary on the present, the cult of subjectivity that is barely distinguishable from the manipulations of marketing. He has reacted by adopting the posture of a rearguard preservationist, keen on preventing the ancient abandoned churches in the French villages from being recycled as mosques. And in Péguy he has found his model.

Péguy’s famous line in his memoir of the Dreyfus Affair—“Everything begins in the mystical and ends in the political”—proposed a general theory of the decline of pretty much everything. And rearguard indignation was Péguy’s response. He wanted to defend the spiritual grandeurs of the past from the lowly politics of the present. It is just that, with Péguy, nothing is what you expect it to be. “Rearguard” was his own term, and, if you look closely enough, sometimes its meaning was “avant-garde.” Péguy made this clear in his poetry. A year after he published his memoir of the Dreyfus Affair, he brought out a book-length poem called The Portico of the Mystery of the Second Virtue, which, under Finkielkraut’s inspiration, I have dutifully read. I cannot say that I adore the poem.

Soupy clouds of Catholic proletarian nostalgia drift across the page, and through the soup we see a sturdy provincial workingman and his calloused hands and his family values and his sturdy sons and everyone’s reverence for faith, hope (the “Second Virtue”), charity, and the mother of sorrows. The poem chants, in rearguard fashion: “It is necessary that France, it is necessary that Christianity, continue.” It is a hymn to the past. And yet, I will grant that something about those swelling chants does seem exciting. The chanting advances in a single free-verse breath, as if intoned by someone in a rapture of joy at the prospect of doing away, at last, with the rhymed couplets of Victor Hugo and the tyrannies of formal meter and 500 years of French literary tradition. “Freedom!” the chanting seems to cry—“Freedom from the syllable-counting of French prosody! Freedom from 1-2-3-4-5-6! Freedom to think and feel and emote in chaotic rhythmic heaves and sobs of one’s own!”

Is this what Finkielkraut has in mind when he invokes Péguy—not the Christianity, obviously, but Péguy’s insistence on some kind of rearguard-as-avant-garde? The piety for tradition that also suggests an occasional libertarian urge to kick over tradition? Or, in Finkielkraut’s phrase, “the great European tradition of anti-tradition”? That has got to be his meaning. A Péguy revival would make no sense without Péguy’s radical provocations.

But really I don’t care. I am not French, and I do not get up in the morning wondering how to interpret whatever scandalous thing Finkielkraut may have said last night that has driven his critics mad. I read him in blissful tranquility across the seas, oblivious to the French news cycle, hoping only to find intellectual stimulation. And he is generous in providing it.

In America, we have not had to confront the kinds of problems that immigrant Islamists have brought to France, except on a tiny scale. We are lucky that way. We have other problems. But I note that, among those other problems, one after another of them has found an intelligent diagnosis in the essays of Alain Finkielkraut—the crisis of historical understanding and the condemnation of the past; the penchant for national self-loathing; the decline of the humanities and book-reading and therefore of cultural memory; the peculiar invisibility of Jewish oppression in the eyes of people who regard themselves as experts on oppression; the various intellectual surrenders to the Islamists; the evolution of customs and social behaviors ever since the revolutionary 1960s; the consternations over relations between the sexes and how to regulate them. I note how pleasing it is to read Finkielkraut’s ruminations on those many themes, and how bracing, and how profitable. I savor his prose melodies. And how infuriating it is to see this most valiant and vigorous and civilized of writers slandered melodramatically in the journals as a man of villainous tendencies and mobbed on the street!

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.