My Emails About André

A conversation about André Gregory’s new memoir, ‘This Is Not My Memoir’

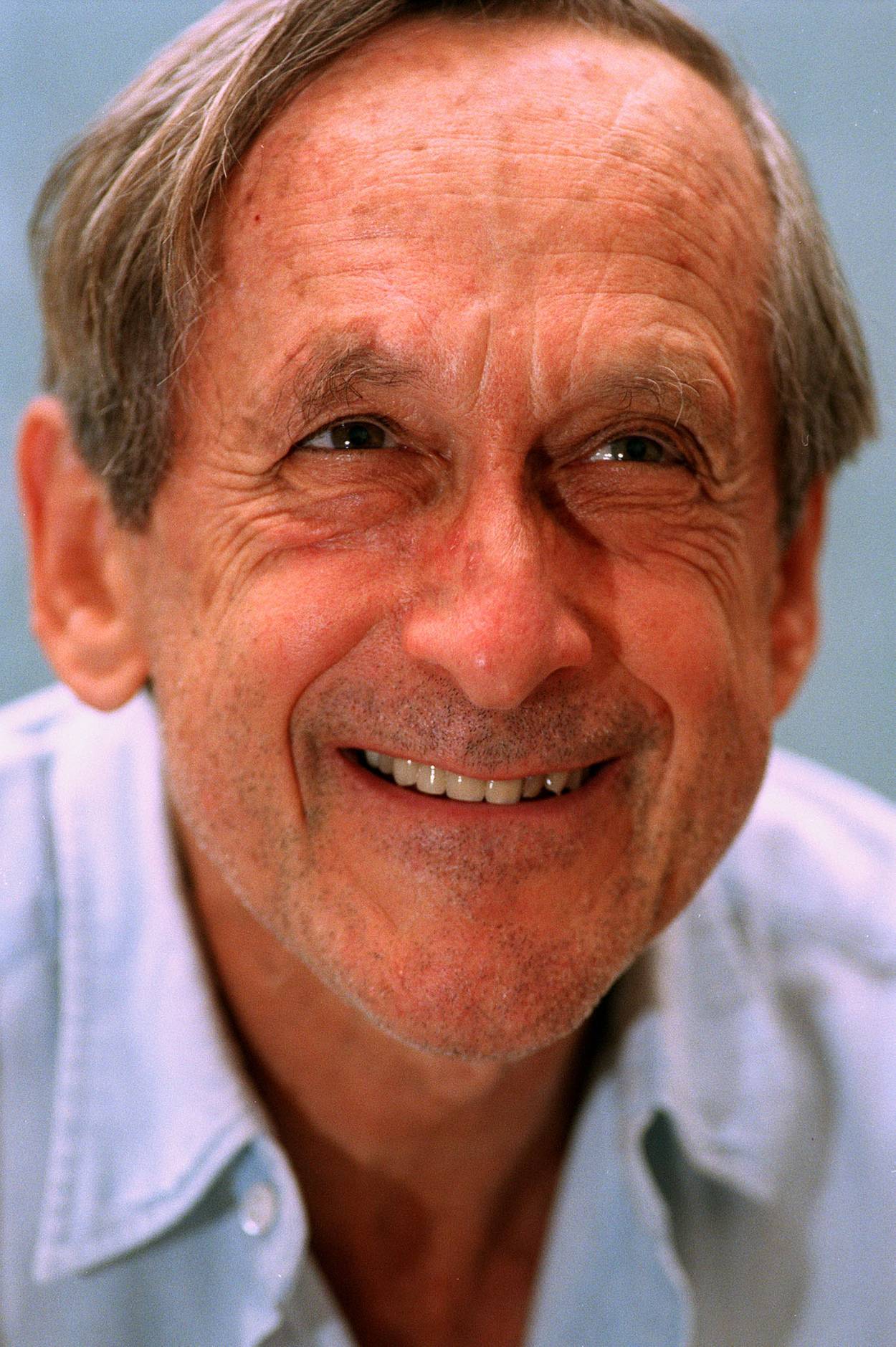

André Gregory is a practically unimaginable figure in today’s American theater—the avant-garde auteur director. Beginning with Alice in Wonderland, his sensational 1970 adaptation of the Lewis Carroll books, made with his troop The Manhattan Project, he defined his unique sensibility on the stage through a body of work that bore the indelible mark of his own imagination. The New York Times called Alice “a nursery tale for a savage nursery” and, in what must be a first in reviewing, thanked Gregory for directing it.

Alice toured for several years and was a global hit. But eventually The Manhattan Project dissolved. Gregory, like one of his idols, the Polish director Jerzy Grotowski, drifted away from mainstream theater and began to experiment with performance art. He also was drawn toward some of the era’s utopian communities. If he continued to be interested in theater, it was not in its commercial iteration.

Today, Gregory is probably best known for several films he was involved with in the 1980s. The most famous is My Dinner with André, made in 1981, an 111-minute-long conversation between Gregory and the playwright Wallace Shawn in which they play rough versions of themselves, auto-fiction avant la lettre. Then in 1989 came Gregory’s Vanya on 42nd Street, David Mamet’s adaptation of Chekhov’s play, Uncle Vanya, starring Shawn in the title role. More recently, he had a second, or third, act when in 2013, Jonathan Demme filmed Shawn’s adaptation of the Henrik Ibsen play The Master Builder, which Gregory had directed in the theater.

These films, rightly considered as other-staged emanations of Gregory’s sensibility, allow audiences to see a robust theatrical intelligence that is part chutzpah, part faith. They also show how much time such work takes to create. In contrast to the standard rehearsal period of three or four weeks, Gregory famously takes years, albeit in bits and pieces, to fine-tune his productions.

Gregory’s new memoir, This Is Not My Memoir, written with the theater journalist Todd London, tells the stories behind some of these great works and also fills in some gaps about his childhood and early career. It reaffirms for me that he is sui generis but also emblematic: He represents a time when theater mattered, when the great 20th-century thinkers and artists tried to create new forms for the theater that weren’t facsimiles of TV, Broadway, or star showcases.

Perhaps I’m romanticizing the latter half of the 20th century—I was alive then, so I know it wasn’t all great! But still, it’s important for people to read This Is Not My Memoir, especially with so much blather about theater artists doing theater on Zoom in the air. Hovering behind the rush to embrace Zoom is the fear that the most ephemeral of arts will never recover, and that the tradition of live theater has reached the end of its creative life span.

It turns out that I wasn’t alone in my interest. Tablet magazine Features Editor Matthew Fishbane, like me stuck at home during the pandemic, was also feeling nostalgic for the lost art of conversation. So we decided that the best way to engage André’s life and legacy was to talk about him. What follows is our own emailed dinner with André. —Rachel Shteir

Rachel Shteir: For the last 20 years, at the theater conservatory where I teach, I begin a course on theories of the theater by making my students watch My Dinner With André. Directed by Louis Malle, the film, which has no plot, just talk, and no characters (the two guys play versions of themselves), became a cult hit. I also insert Gregory’s other films into my syllabuses wherever I can. Last spring, as COVID began, I made some students watch A Master Builder, Jonathan Demme’s 2013 adaptation of Gregory and Shawn’s gripping version of Ibsen’s weird late-life tragedy, The Master Builder. I haven’t yet figured out how to work in the 2013 documentary that Gregory’s wife, Cindy Kleine, made about him, André Gregory: Before and After Dinner.

I have thought for a long time that students need more than anything to see that someone like Gregory exists. And if anything, now, that project is probably more urgent.

Gregory is representative of several vanished categories in the American theater. One of these categories is the director as intellectual, as someone who cares about ideas for their own value. Another is the director as enfant terrible, which seems practically gone from our conformist times. But even harder to imagine today is that Gregory takes the theater seriously not just as a career but as a vocation.

Then too, paradoxically he is also emblematic of another bygone trend that my students sometimes find inexplicable or worse: the theater director as celebrity. Theater had a more glamorous air in his era. His 1970 adaptation of Alice in Wonderland, which used techniques he learned from one of his mentors, the Polish theater director Jerzy Grotowski, made him famous. Both that production’s vitality and fame are clear in the Avedon photos widely viewable on line. (He was friends with Avedon.)

But the three amazing movies that Gregory has been associated with—My Dinner with André, and the filmed versions of his theatrical direction of two brilliant 20th-century plays—make him essential for our vulgar, politics-and-social-media-saturated, cancel culture era. Take My Dinner with André. The movie is a philosophical conversation about the meaning of the theater—or really art—and life. It is a dialogue about the philosophical question of whether you can turn your life into art and what that means. It is also about Gregory’s spiritual journey both into and away from the theater.

Like another one of his idols, the German playwright and theorist Bertolt Brecht, Gregory wanted (and wants) the theater to be more than a show. He wants it to be sacred. It was also his salvation, from his tyrannical Russian Jewish parents, something I learned in his memoir.

But the movie is not just a platform for Gregory’s point of view. The title of the movie is My Dinner with André so it is skeptical about Gregory’s whimsical, pompous, paranoid, and ultimately humane ideas about how artists should live and work. The “My” refers to the perspective of the character of Wally Shawn. It uses Wally’s point of view as a way to engage, cast doubt on, and even puncture André’s ideas. It is like the dialogues of the ancients, set at an elegant French restaurant. ...

Matthew Fishbane: And you know who the real star of that movie is? Jean Lenauer, the Vienna-born director and actor, who as the waiter at André and Wally’s table uses his wizened face and a subtle tilt of his giant smoke-stained, white comb-over to be part Greek chorus, part Bergman-like Death, and part eye-roller extraordinaire: Can you believe these guys? Withering hardly covers it. Now: Do Wally and André deserve that?

That is the maddeningly paradoxical joy of André and his ilk (and I disagree he is sui generis, but more on that later): their ability to be both impossibly pretentious and at the same time endearing. What we learn from the memoir is that “disarming” is a family trait inherited from Soviet Jewish war refugee parents who hustled their way into a postwar New York-Los Angeles life as hosts of Hollywood A-list poker parties and Fifth Avenue private school socialite-ism that included George Burns, Greta Garbo, the Marx brothers, and Errol Flynn, who was briefly Gregory’s mother’s lover, in between bouts of blackout drunkenness. They were also terrible parents.

I mean, take the first line of this mixed-bag new memoir: “When I was a freshman at Harvard in 1952,”—ugh, you smug Ivy League snob!—“I had horrible roommates and got slightly depressed.” Great! Can’t wait to hear about how horrible your life was! Any sane person would slam the book shut right then and there and tell this coddled entitled jerk to go tell his cockamamie stories to someone who gives a shit. But before the end of the page, as you note, we’re in a burlesque-hotel with a stripper called Princess Totem Pole, and all our weapons are sheathed, and the guru has charmed and tamed us. Call me Wally.

Taming and tameness are of course central themes in My Dinner with André, at the heart of André and Wally’s debate over whether it’s better to be comfortable (-ly numb) or uncomfortable and searching, but lost—whether to live to make art or make art to live. I imagine most of your students land on Wally’s side—“I’m just trying to survive!”—against the man-child of privilege who has the luxury to take himself on a whim to Tibetan monasteries to be blissed out by the love-glow of a German-Buddhist Rinpoche, or to “Dick” Avedon’s cliffside Montauk bungalow for a ritual burial and rebirth prepared for him by his cool artsy theater friends.

The question for today’s world of self-absorption is if we can still appreciate André Gregory without resentment. What do you think?

Rachel Shteir: I love Lenauer’s stony presence and from the memoir I learned that he was not a trained actor but rather worked in the film department of MOMA. So he was an amateur, which is interesting in terms of Gregory’s fascination with actors who are able to do more than play realistic psychological characters. But Lenauer’s function in the film, which you so richly describe, to me is also further proof that one is not meant to wholeheartedly endorse André’s at times smug perspective. In other words, I don’t think the film is suggesting that you embrace unequivocally what you rightly call André’s “pretentiousness.” But at the same time, given the state of American culture—and theater—I’m not going to condemn that pretentiousness since it also involves Gregory paying homage to the great European modernists (Brecht, Grotowski) that he took inspiration from. And given “today’s world of self-absorption,” as you put it, I could actually stand a little more of this pretentiousness. Must everything be Real Housewives of Beverly Hills?

These modernist guys are theater artists (yes, they were all guys and even worse, white guys), all advocated for other kinds of representation of stage besides that of the great naturalist theorist and director Constantin Stanislavski. For students (the group I’m often foisting the movie on), it’s important to know that there are living people who take those theories seriously, even if some of those living people are “men-children of privilege”!

So while I agree with you about the Harvard bit—totally, cringingly awful—as are some of the bloviating bits that come out of André’s mouth in My Dinner with André and in the memoir, I think many of these bits are staged as a kind of high-low pastiche to get us to think more expansively about the question of how to be an artist. Like in the memoir the Harvard line and the striptease bit are on the same page.

You ask at the end of your lively summa “if we can appreciate Gregory without resentment,” but to me that’s not the question. I don’t see why we must separate the two responses. I want the thrill of both resenting and appreciating at the same time; i.e., Gregory’s father’s money allowed him to go on this journey, but his discoveries about himself—his own transformation—and his contribution to the arts went way beyond that. As you know, there are a lot of Harvard grads with wealthy parents who go straight to Wall Street. Who would work in the arts if they had a choice?

Another fact I learned from the memoir was that Gregory was first drawn into the theater by rage at his classmates. But this is hardly unusual. I am reminded of Bill T. Jones, who, when asked why he kept creating, said “spite.” I think it’s important for students to see that the beginning of something does not have to be the end. And that Gregory’s irritating qualities don’t diminish his brilliant work, which is what I mean when I say he is sui generis.

I also want to say that in This Is Not My Memoir, where Gregory writes more than anywhere I’m aware of about his moneyed father, I learned that he was also possibly a Nazi collaborator and mentally ill. These latter facts strike me as being as important as the wealth. Gregory spent years in analysis trying to deal with them, with the (typical of that era) frigidity of his terrible parents. He writes that he never loved his mother, who (again I read this in the memoir) on her deathbed renounced him and demanded caviar.

Gregory is well aware of how the failures of his parents shaped the major failures that he had as a husband, as a father, even as an artist. But he can’t unlive his life or change his past.

As to your note about my students: They, as I said, have mixed responses to the movie and the memoir. (Full disclosure: I read long passages of the memoir to them over Zoom.) Some were charmed, others horrified, some both. Some were/are bored, although in the memoir Gregory says what my high school chemistry teacher said: When you’re bored it’s about you.

Matthew Fishbane: I’m sorry I gave the impression that Gregory’s privilege, race, or gender is a matter of “social justice” or of any real import. I think it’s a near tragedy to view his work through that lens—at least, it makes me sad.

His pretension, on the other hand, is, as you say, an aspect of his masterful artistry and worth another look. And I love his work. But when I say that he isn’t sui generis, I think of other literary-minded white male gentlemen adventurers (whose group-signifiers, again, I don’t care about) who I also admire and envy: Bruce Chatwin, Peter Matthiessen, Ryszard Kapuściński, Patrick Leigh Fermor, Spalding Gray, and others who mined out-there personal experiences for their storytelling arts. All credit to them: Any of us can find the nerve to sign up for a Lakota sweat lodge, or ride ponies across the Mongolian steppe, or get lost near the Big Bend of the Rio Grande high on peyote (who, me?), but only the artist can transform any of that into something the rest of the world might gain from. But Gregory is not alone in doing so. You could argue that Instagram has moved in on their turf.

What interests me isn’t the pretension, but the ability to overcome self-doubt which can in turn come across as pretentious. I do think privilege plays a part in that: The financial safety net changes the equation of risk, as Gregory acknowledges in the memoir and in My Dinner with André. “Privileged men know they can pay or charm their way out of anything,” he writes. His late-in-life turn to watercolors and self-portraiture, for example, which leads to a gallery show instead of a scrapbook collection: Would it, were he not a noted actor and theater director first?

Or, let me try to say this through a personal anecdote, if you’ll indulge, since André likes to insist that there are no coincidences.

My Dinner with André came out in October of 1981. I was 10 years old at the time, in college-town Virginia, which means impossibly peripheral to the remote world of New York art-house cinema, let alone experimental theater, or the moneyed Upper East Side Jewish immigrant aristocracy. (Wally, in the film, about his lost innocence: “When I was 10, I was rich, I was an aristocrat! Now I’m 31 and all I think about is money.”) Yet, somehow, probably through my father’s pretensions—he was a physics professor and is still a Francophile—I saw the film: In our provincial backwater I’m guessing it was a second or third run at our own art house, after the film initially flopped (as Gregory describes in the memoir) and after it got its cult following in the wake of Siskel and Ebert’s unexpectedly glowing review. (My father did watch Siskel & Ebert on occasion, and probably got the idea from them, when critics still held that power.) So, let’s assume that I saw this film in 1982, probably too young to get it, but still amazed.

But something else happened at the end of 1981, which was that my mother committed suicide. So here is André Gregory’s “André Gregory” character, as Louis Malle’s camera zooms slowly in on his face, describing a parlor game he and his friends engaged in one Halloween night out on “Dick” Avedon’s Montauk retreat, in which he was asked to write his last will and testament, and his friends had dug a pit for him, and he was ceremoniously lowered into this grave, covered with planks, covered with dirt, left there for 30 minutes, and then “revived,” which led to much dancing and merrymaking on the heaths of coastal Long Island—and, well, perhaps you can see why that kind of fun and games can be off-putting. It’s a privilege to be put to death in a way that allows for a resurrection.

Gregory and Grotowski came to find performance in the theater to be superfluous, that the ultimate performance art was living, and that our Jungian 20th-century alienation made us inhabit roles. In fact, the ultimate performance art is dying, and I’m willing to bet that Gregory’s deep understanding of that may well be what hampered his output for so much of his life.

But since there are no coincidences, what brought you to him and his work, exactly?

Rachel Shteir: Matthew, thanks for clarifying about your take on André’s, uh, privilege, a word that I loathe. Also I should say re his late-life painting, I mean, I think it’s great that he’s doing it, but care about it way less than the Hedda Gabler he teases us with. And I’m not sure I agree with you that he has conquered self-doubt. But if he has, he’s been in a lot of therapy and he’s in his 80s, so I guess my hope is that that’s wisdom, not $$$.

But let me change the subject here because of course I was jolted by your anecdotes. First, uh, I would like to hear about Big Bend! Second, about your first viewing of My Dinner with André. I am trying to understand what it must have been like for you seeing it as a boy who had just tragically lost his mother. I don’t know if I can. And I agree with you that André’s talk about staging his own suffering when put next to real suffering can sound insensitive. Like in the movie, when Wally talks about his beloved electric blanket, André delivers a lecture about how that blanket prevents you from having an existential breakthrough when of course, actually Wally just wants to warm his toes.

Yet here too as usual, I am split. I think of this tendency as obnoxious and maybe it does come from having that financial cushion. But I also think of it as part of a Gallic tendency to lecture (he was born in France), which I am kind of predisposed to.

However, in the end, I’m not sure André’s suffering occludes other people’s suffering. He appears to be empathetic, although maybe he is merely intuitive, a kind of Geiger counter “regarding the pain of others,” to use Susan Sontag’s phrase. He is certainly interested in how individuals work out their agony in their art—and ultimately how he does this.

In the memoir, he writes about Vanya on 42nd Street, which I am again waving about as my piece of evidence as to why he IS sui generis—there is no other adaptation of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya that so illuminates the play as his 1989 movie. He was directing it at the time when his wife, Chiquita, was dying and in fact, as he tells in the memoir, a number of people in the Vanya cast were struggling with their own grief and loss off stage. Perhaps that’s what gives the film its incandescence. I miss this kind of sensibility in our present moment. It doesn’t make him a better person, necessarily.

To your question: I don’t remember when exactly I first saw My Dinner with André. The year it came out, I was a senior in high school. I doubt that I saw it at the Garden Theatre on Nassau Street in Princeton, where I grew up. (I do remember a few years earlier when Looking for Mr. Goodbar came to town, dragging my mother to see it with me, but that’s another story!) I think it’s more likely that I first saw André in Chicago, at DOC films, the University of Chicago film club, where they screened such things. I certainly spent my college years and many years after that admiring many of those “white gentlemen adventurers” you write about above, especially Bruce Chatwin, all the while trying to figure out how women—how I—could fit into the picture. Maybe my enchantment with female travelers from the 19th century, Victorians like Isabelle Eberhardt, who dressed as men and gallivanted through the desert comes from André.

I want an actor who can fly. I want scenery made of human bodies. I don’t want stage lights, I want light that emanates from the actor’s body.

I think I had seen My Dinner with André by the time I went to the Yale School of Drama in the late 1980s, but by then, Gregory’s antics—like his attempt to find a real severed head in the New Haven morgue for his production of The Bacchae—were so distant from our own squabbles in the classroom and the rehearsal hall as to seem from a different planet. In the memoir, there are a lot of such stories and all of them make theater sound exciting.

But there are two things we haven’t talked about at all here that I want to bring up. One is Gregory’s relationship to his Jewishness. I wonder how you see that, if you think his referring to Nazis and totalitarianism, even his own such tendencies in My Dinner with André, are excessive. To me reading about his father provided a backstory for what seems faintly embarrassing or maybe I’m looking at it through Wally’s eyes? And to get back to my students, I’m not sure how they see this part of the film, if they understand the historical context of it.

And then there is the fact that there is so little talk about sex. Not that there need be any sex of course in a movie about dinner! But André does joke that any sequel will contain more sex.

Matthew Fishbane: Yes, I loved that part of the memoir: André and Wally agree that though they never will make a sequel to My Dinner with André, if they were to, it would be the two of them, Gregory at 90, Shawn at 80, but instead of a dinner, they would be “old men in rocking chairs on the veranda of an Adirondack hotel.” How wonderful would that be? Two old Jews, one a professed atheist—with all the sexual hang-ups of 20th-century Jewish American males, but uninhibited through their deep friendship and the fact that their sexual lives are a closed book—joking, reminiscing, storytelling about every kind of sex they had, didn’t have, imagined, were afraid to imagine, and the women (or men!) who came between them in the intimacy of their theater work, and so on. I wish they would make that sequel.

But it’s not true that sex isn’t mentioned in My Dinner with André: André talks about the moment of complete forgetting that accompanies orgasm and the way the world rushes in so quickly, and how hard it is to reach that same inner calm through disciplined means. Dualities like these—which cause you to say that you are “split”—are everywhere in André’s work, and yes, they run strong in his own Jewish family: His father was “a shtetl Jew [who] fashioned himself like a WASP gentleman golfer”; his mother, a rough Soviet refugee who “had never seen a lobster and didn’t know how to peel a banana,” but who came to bed Errol Flynn in Hollywood. And great-grandfather Haim, who did nothing: “he was a learner,” which is what Gregory imagines himself to be, in his own way.

This heritage is fascinating because it represents one prominent strain of the American Jewish 20th century, which is no longer (along with the “vanished categories in the American theater” you described above). Ultimately that’s the memoir I wish he had written, as a living witness, more focused on his life and his parents’ lives than on philosophical backstage backstories that seem exclusive to the theater-obsessed and a tad too far into self-deprecating guru-dom. But then again, Talmudic commentary is likewise humbly insular, and he did say that This Was Not His Memoir.

Rachel Shteir: I was rereading This Is Not My Memoir last night and there are so many quotes and stories in it that I love. I probably have scanted the influence of the Polish director Jerzy Grotowski on Gregory. It was Grotowski, I think, who gave Gregory his idea of rehearsing without the onus of performing for an audience, without the burden of a box office, marketing, everything that has now taken the lead in so-called mainstream theater. In his 1968 book, Towards a Poor Theatre, Grotowski tries to give actors ideas for how, by using their bodies, they can compete with television and these ideas do not involve realism, for the most part. It was Grotowski who inspired Gregory’s first hit, Alice in Wonderland. At one point, Gregory, trying to describe the “miracle” theater he is looking for says, “I want an actor who can fly. I want scenery made of human bodies. I don’t want stage lights, I want light that emanates from the actor’s body.”

Perhaps some will find this silly or impractical but I find it moving. There are a number of inspirational lines in the book. A memorable one is where Gregory quotes the Swedish actor and writer Erland Josephson: “what I would now like to do is find a teacher who could show me how to walk down to the footlights and—by just standing there, by doing nothing—be like a lighthouse illuminating and giving hope to the audience.”

That is how I felt about the book—that Gregory was his own lighthouse. We need more lighthouses.

Rachel Shteir, a professor at the Theatre School of DePaul University, is the author of three books, including, most recently, The Steal: A Cultural History of Shoplifting. She is working on a biography of Betty Friedan for Yale Jewish Lives.

Matthew Fishbane is Creative Director at Tablet magazine.