A Bird With Feathers

‘I am just a human body, not as good looking as I once was, but not yet the small gathering of ash I will be’

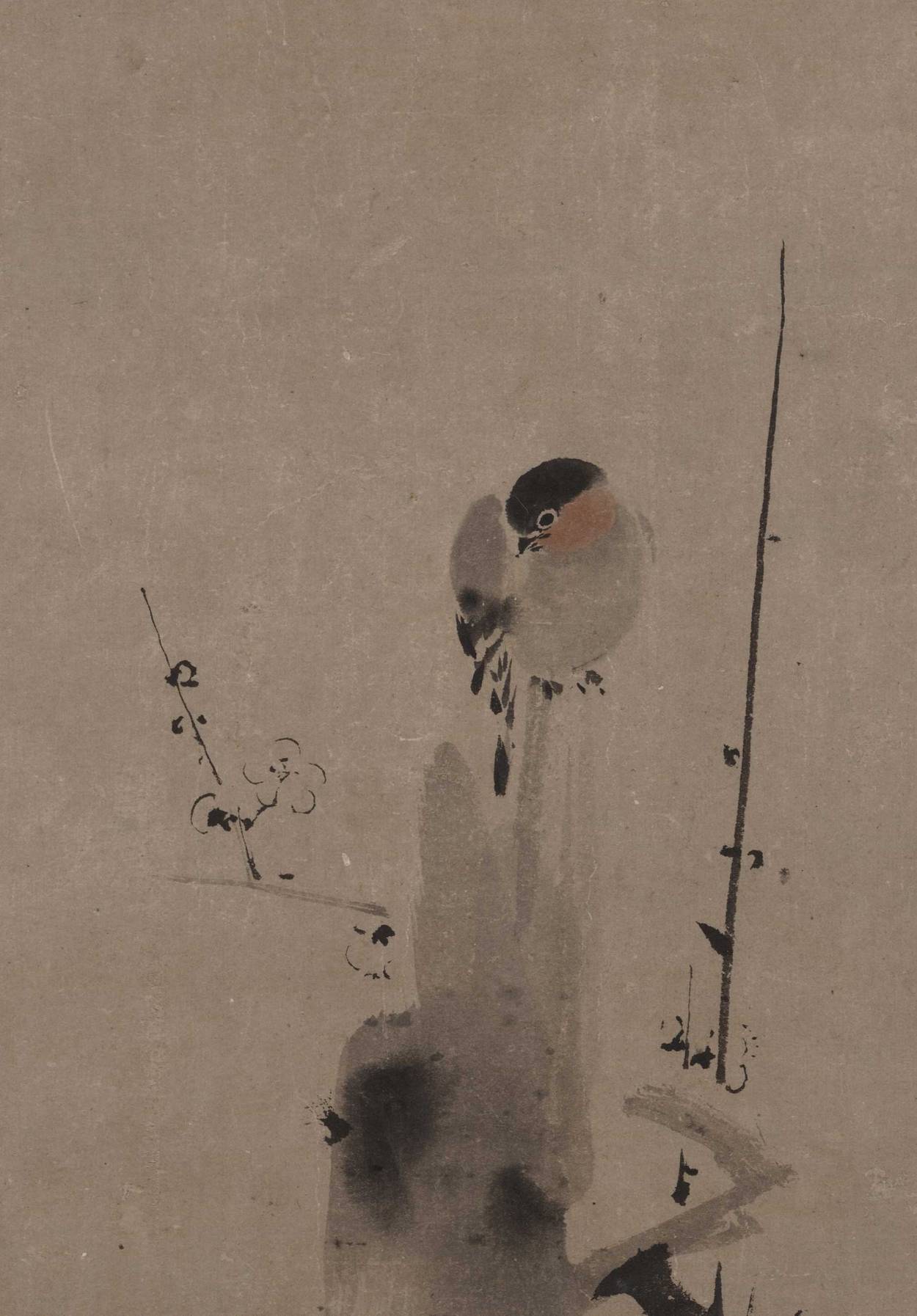

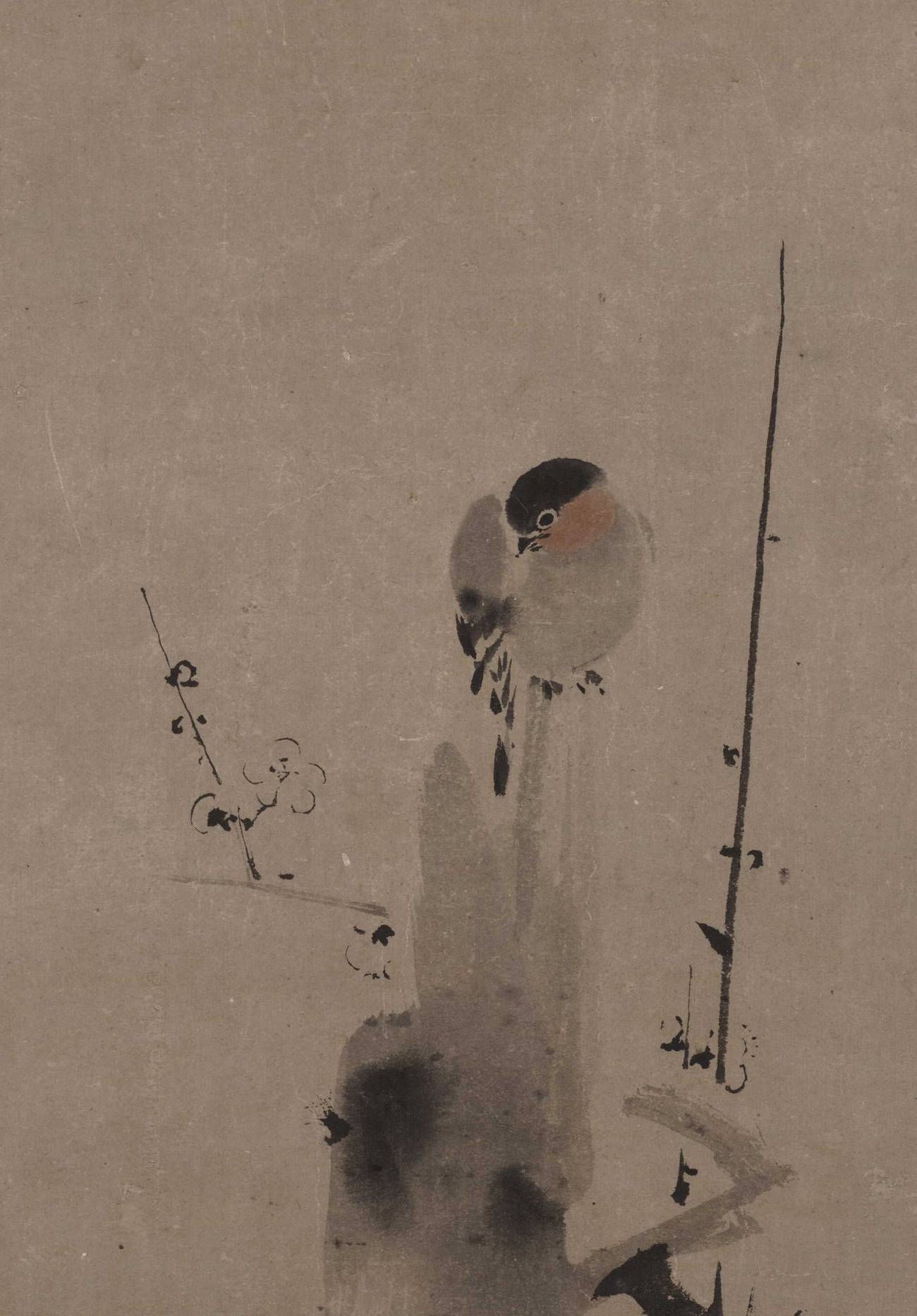

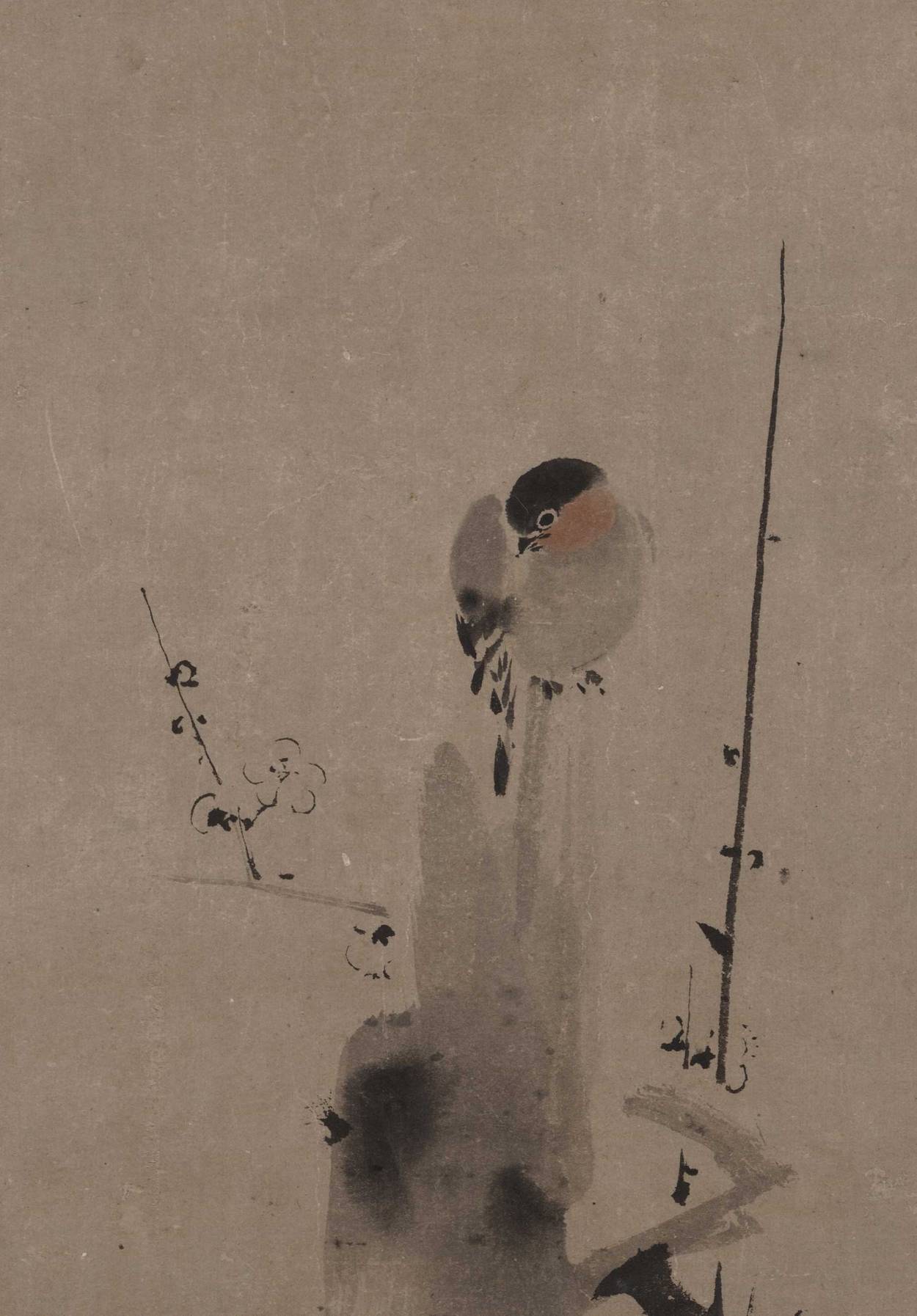

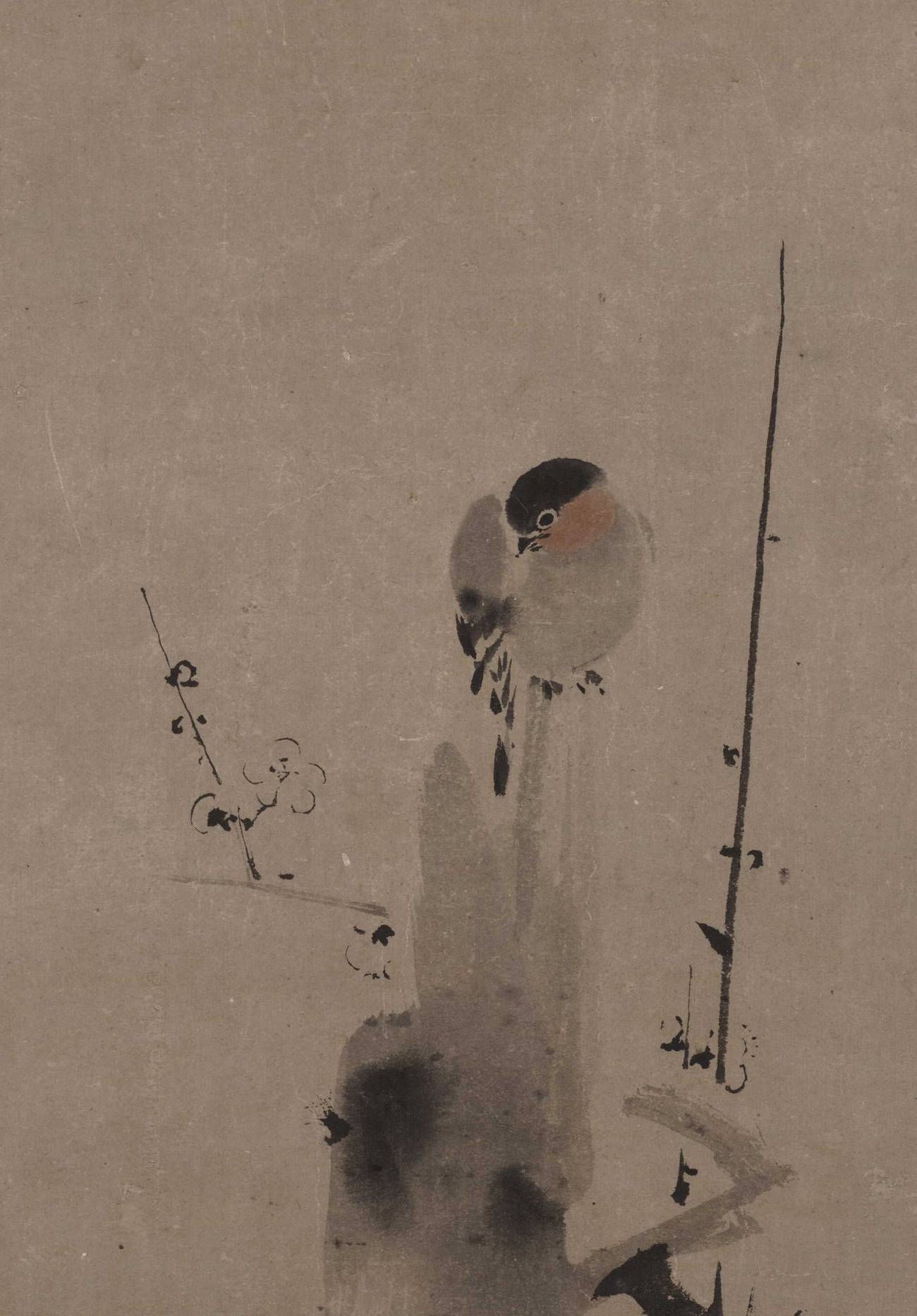

Faith is a bird with feathers or is that Hope? Faith is good for you like orange juice and can bring you joy like ice cream. Faith is like believing that Elijah enters when you open the door for him at Passover. If you lose Faith it is very hard to find again. Even if you find it you will never trust it the way you once did. Faith answers many questions but it is like reaching the top of a mountain. You can see other mountain tops all around and you still have to climb down.

Faith gives you an option to anticipate an afterlife. As if the molecules that you shed in the grave can reassemble themselves along with your shriveled heart muscle in some distant place and you can be you again. This belief while obviously comforting raises many questions. What age is my reconstructed self? What ideas and memories are in my head? Who will love me and whom will I love and if I no longer have the capacity or need to love, why bother?

Ironically I suppose, Grace Paley named her alter ego character Faith although her character was clearly Jewish and Jews are more interested in stories than in devotion. Although there are excellent tales of devotion, they are mostly for little children so they can sustain the magic of belief as long as possible. The Wise Child however knows that a good story is a delight without any direct reference to truth or reality. The Simple Child does not care and the Wicked Child has more profitable things to think about.

There is such a thing as a death-bed confession but I wonder if such conversations aren’t more wish than fact. Our sins seem more pervasive, more terrible, more hard to admit as time goes on. Certainly it seems to me that my last moments might be better spent in tenderness rather than righteousness addressed to the fading self. Where is the judge and who is the judge and who is judging the judge? I can think of a long list of repairs that the judge ought to make to His creations before He looks at us askance.

None of this is my business. I am not a philosopher or a monk or a guru or a holy woman who bathes the feet of the poor. I am just a human body, not as good looking as I once was, but not yet the small gathering of ash I will be.

When the man I loved, the father of my children, fell on the lobby floor of our Riverside Drive apartment building one cold December night some years ago, I looked in his eyes and said, “Should I call an ambulance?’ “What for?” he said, and the light went out of his eyes and I knew he was dead.

He was dead-gone-vanished—unreachable by séance, by memory, by airmail, by email, by fan mail. He left behind some papers published in professional journals, a library of 19th-century fiction, some paintings of dubious provenance, and the ever-flowing images of his life stored in the minds of his wife and children. And a bill from his ex-wife for the December forever monthly alimony he hadn’t paid because he had died.

One thing I know for sure: There are atheists in fox holes. How many I do not know. No one would choose such a position but for those of us who hold it, like the color of your eyes, only fraud, self-deception, changes it.

One summer day as we were driving to the beach and he was already pale and tired I asked him if he would like to be buried or cremated and he said why would I care? Do what you want. All right, I said. But it wasn’t right, not at all.

I thought about releasing his ashes into the Atlantic Ocean but then I thought they might stay intact until they reached the Normandy shore where he had survived a landing on the second day of our invasion. He had been 18 years old. He was one of a group of five men who tended a large communications machine that stood behind the trenches and sent messages to generals in other places. It was an early computer. The guys who kept the machine dry and working had unpacked one canvas bag and filled it with Thomas Mann, Proust, and Tolstoy translations and some German biology books. They dragged those books all the way up to the gates of Auschwitz.

German science was thought to be the best in the world. He told me that on our first date.

I didn’t want his ashes on the Normandy beach. He wouldn’t have cared. But I did.

I suspect that an ash cannot cross the ocean intact.

If he were here I would ask him.

If he were here the smell of freshly baked bread would drift down the halls of our apartment. If bread is the staff of life what is its absence: something wrapped in plastic?

And so I come to the point. Snow only falls down, also rain. This is gravity. Time only goes forward and only in memory or dream or in novels does it rewind. So that people have the illusion of growing up when in fact they are growing down, sliding down, slipping down and will like all the snowflakes that rain down on us, melt away in the rising sun.

This sounds somber but it isn’t. It is just the way it is. So I will imagine taking my sled to the park and I will be wearing my warm gloves and boots and my nose will turn red and I will watch the children who are rehearsing again and again the direction of their lives.

Anne Roiphe is a novelist and a journalist.