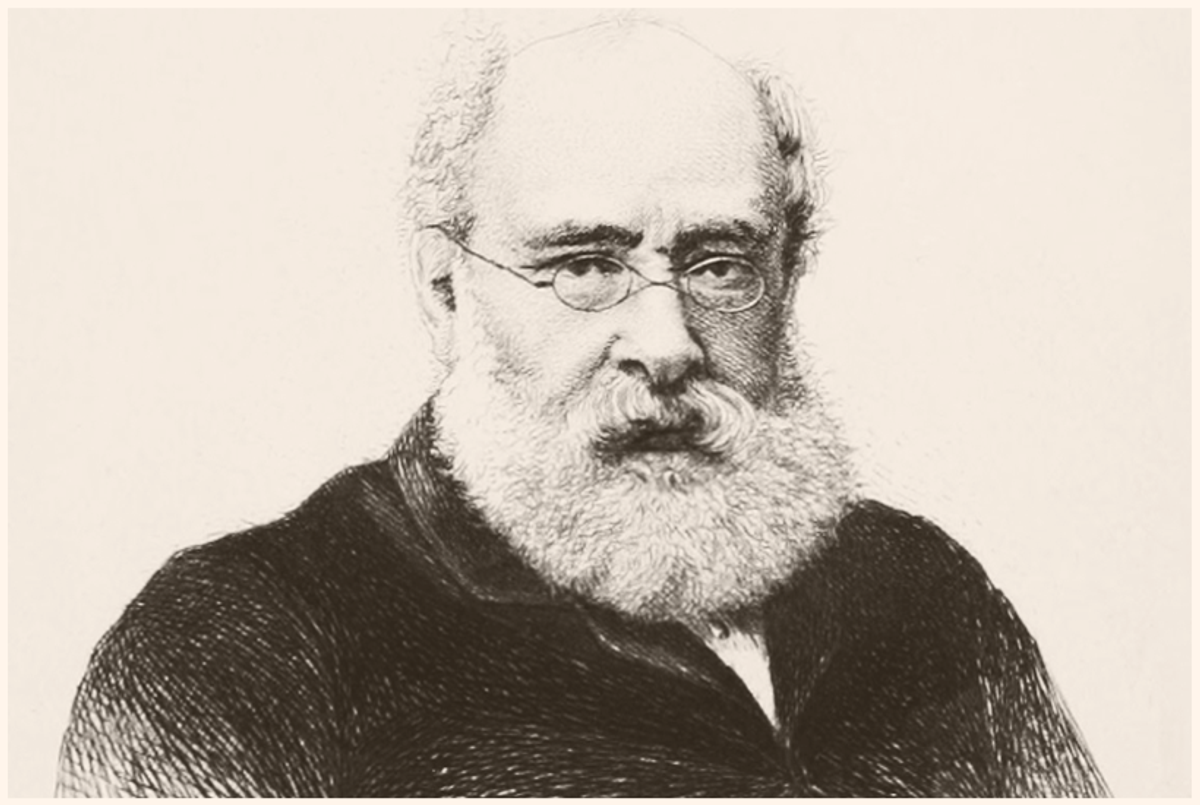

“I was big, and awkward, and ugly, and, I have no doubt, skulked about in a most unattractive manner. Of course I was ill-dressed and dirty.” Anthony Trollope’s An Autobiography (1883) is remarkable for a number of reasons. One is the searing honesty of sentences like this one and his candid, sometimes harsh assessment of his own works. Another is a Romantic embrace of abjection, at odds with the measured calm of his novels. Even the language is different: less polished, more emotional. His failed barrister father, Trollope says, was “occupying dingy, almost suicidal chambers”: a phrase impossible to imagine in his fiction.

Today, this tone makes An Autobiography more accessible than the novels. Perhaps this is why Oxford University Press has come out with a new edition that seems aimed at the academic market. It includes notes that Trollope (1815-1882) wrote about Jane Austen, unpublished in his lifetime; excerpts from his “biography” of Thackeray and an essay on Hawthorne; a short lecture defending the novel, “On English Prose Fiction as a Rational Amusement,” part of a charming essay called “A Walk in a Wood,” and editor Nicholas Shrimpton’s estimable 13-page introduction. All of this is worth having, but those on a budget should note that An Autobiography is available for free on Kindle (ranking around 24,000 among free offerings at the Kindle store). So, happily, are most of Trollope’s works; he wrote 47 novels and 18 works of nonfiction in addition to short-story collections.

Trollope did not bring out An Autobiography in his lifetime, relying on his son Henry to see it through to posthumous publication, which he did. At the time it was published—a year after Trollope’s death—An Autobiography was thought coarse-grained and philistine, little in sympathy with the pleasant notion of the novelist as a cloistered aesthete unconcerned with productivity, much less with money, waiting on the Muse for inspiration rather than eying the household budget.

Trollope brought this criticism upon himself—as perhaps he knew he would—by emphasizing his grinding work ethic and discussing at length the financial aspects of the literary life. It was unlike the stereotype of the gentleman, with his sprezzatura and his disdain for money, and yet Trollope had devoted more ink than perhaps more than any other writer to the question of what makes a gentleman or a lady. Yes, there is nasty anti-Semitism in Trollope’s depictions of Jews, but there is also identification.

Trollope’s unsympathetic readers seem never to have drawn the connection between his lauding of industry and concern with money and his family’s financial instability, which he dwells on in An Autobiography. Trollope’s childhood was overshadowed by his family’s battle to retain their gentle status amid financial catastrophe. At one point, the young Trollope had to help smuggle the family’s sparse treasures out of the house as the bailiffs arrived to seize their property to pay his father’s debts. Due to family poverty, Trollope had to walk 12 miles a day to and from his fashionable school, Harrow, arriving dirty and disheveled. There, and at Winchester, he was bullied and beaten constantly and learned next to nothing but Latin and Greek, and that not well. Of one incident of bullying, Trollope wrote, “All that was fifty years ago, and it burns me now as though it were yesterday. … I remember their names well and almost wish to write them here.”

Life for the Trollopes improved briefly when his mother Frances (Fanny) Trollope returned from an American visit—a failed attempt to set her second-eldest son up in business in Cincinnati—and wrote her first book about it at the age of 50. It was a smash success, and Fanny supported the family thereafter, publishing 114 books. (Perhaps only the son of a mother who published 114 books would find it necessary to boast of his 47. Trollope’s first break came from his mother’s publisher.) Trollope makes it clear that his astonishing work ethic and energy mirrored those of his parents. Fanny “was at her table at four in the morning, and had finished her work before the world had begun to be aroused.”

Trollope also relates almost casually how his mother nursed her husband, a son, and a daughter through their deaths by tuberculosis. Of her six children, four died of tuberculosis while young. Only Trollope and his oldest brother, also an author, lived past young adulthood. After giving up the law, his father labored on a massive ecclesiastical dictionary each night after putting in a full day as a failing gentleman farmer. Eventually he too succumbed to tuberculosis.

Trollope expressed pride in An Autobiography of his fearsome industry, boasting that he often began one 600-page novel the day after finishing another. “It was my practice to be at my table every morning at 5:30 a.m. … I could complete my literary work before I dressed for breakfast.” After breakfast, Trollope left for his job as a high official in the Post Office, where he worked for 32 years; he claimed credit for introducing the institution of street mailboxes throughout Britain. He resigned only in 1867, after publishing about a dozen novels. Then he took up editing a literary magazine for three and a half years.

Trollope wrote 250 words every 15 minutes, 10 pages a day: enough for three three-volume novels a year. And he made no bones about the fact that he chose his publishers by how much they paid him, listing the sum he received for each of his books as a coda to An Autobiography. Trollope was candid about the finances of his literary life to a level of detail that would raise eyebrows even today. (“He agreed also to pay me £30 more when he had sold 350 copies, and £50 more should he sell 450 within six months.”)

Yes, there is nasty anti-Semitism in Trollope’s depictions of Jews, but there is also identification.

Yet despite his emphasis in An Autobiography on routine and steady work, there was a strong streak of Romanticism buried just beneath the surface of the man. Trollope wrote of “living with” his characters imaginatively, saying that for the novelist, “They must be with him as he lies down to sleep, and as he wakes from his dreams. He must learn to hate them and to love them.” As Shrimpton emphasizes, Trollope’s communing with his characters “has a distinctly Romantic flavor.” To the charge of mercenary production, Trollope made clear in An Autobiography that he saw the difference between writing “not because he has to tell a story, but because he has a story to tell” and of novelists who have “distressed their audience because they have gone on with their work til their work has become simply a trade with them.” As the description of living with his characters makes clear, writing was a joy to Trollope.

Anyone who hasn’t already read a few novels by Trollope ought to do so immediately, but anyone who has had the pleasure of exploring the novels ought to read An Autobiography. It is a counterweight to them, in which Trollope shrugs off the endless preoccupation with ladylike and gentlemanly behavior and unburdens himself emotionally, letting the chips fly insofar as his native reticence allowed. I also see An Autobiography as the place where Trollope explores some of the issues he investigates with his many Jewish characters: how people would act and speak and think who were not English ladies and gentlemen.

***

Trollope wrote a great many Jewish characters, considering that at the time Jews comprised less than half of 1 percent of the English population. Nina Balatka (1867), obscure because it is set in Prague, concerns the courtship by a worthy, wealthy young Jew, Anton Trendellsohn, of an impoverished but virtuous Catholic girl. There is also a darkly beautiful, tragic Jewess named Rachel—who helps the young couple unite, though she loves Anton herself. In the better-known The Eustace Diamonds (1872), a thoroughly bad-Jew-turned-successful-Christian minister, Mr Emilius, becomes the husband of the wicked but charismatic Lizzie Eustace. She views him as “a nasty, greasy, lying squinting Jew preacher. … But there was a certain manliness to him.”

Two Trollope novels, Phineas Redux and The Way We Live Now, depict multiple Jews or people who may be Jewish in origin, some of whom are commendable and some villainous. In Phineas Redux (1873), the gallant Madame Marie Max Goesler (the widow of a Jew, if not definitely Jewish herself) faces off against the evil Dr Emilius, saving the politician Phineas Finn from the gallows—and ends by becoming his second wife. One critic, Shirley Letwin, has argued that Madame Goesler is actually the most perfect “gentleman” in Trollope. (I owe this reference to the English critic Bryan Cheyette’s doctoral thesis, available online.) Cheyette, however, believes that for Trollope a “good Jew” is one who, like Goesler, renounces the ambition of marrying into the English aristocracy. (He doesn’t say so, but this is basically the stance of Walter Scott’s Rebecca in the 1819 Ivanhoe.)

Cheyette has also pointed out the importance of Trollope’s hatred of Benjamin Disraeli in understanding some of Trollope’s later novels. Trollope was a Liberal, Disraeli a conservative; but perhaps worse was the fact that Disraeli had supported himself by writing novels from the age of 23, publishing 18 in his lifetime—and still had time to run the world, while Trollope failed miserably in his attempt to enter Parliament in 1868, as he notes in An Autobiography. Trollope’s venomous comments on Disraeli’s novels refer to anti-Semitic stereotypes. Charging him with falsity, Trollope speaks of “that flavor of hair-oil, that flavor of false jewels, that remembrance of tailors.”

Yet for Trollope, the profession of writing novels involved at least one stereotypical Jewish trait. In The Prime Minister (which depicts a prime minister as stodgy and useless, but also as helplessly sincere, as Disraeli was brilliant, effective, and ruthless), the upright old gentleman Mr. Wharton refuses to allow the marriage of his daughter to the evil Ferdinand Lopez, a Jew. Trollope comments editorially that the world no longer cared whether men had “the fair skin and bold eyes and uncertain words of an English gentleman or the swarthy colour and false grimace and glib tongue of some inferior Latin race.” Professionally, Trollope certainly is with the people of the glib tongue, not the stammering gentlefolk. There is perhaps no 19th-century English novelist as “glib” as Trollope.

Trollope scholar James Kincaid has argued that we ought not to take Trollope’s invective at face value:

[V]ery often Trollope’s objective descriptions, particularly of bizarre persons or unsavoury motives, imperceptibly alter, drop the objectivity gradually, and move us inward. We suddenly realize that it is not “it” being discussed but “we.” Trollope does literally shift the pronouns, adopting a technique of the sermon, a standard device of application. He so disguises the technique, however, that we are led not to contemplation, the end desired by the sermon, but to radical identification—with Ferdinand Lopez, for instance, one of the most repellent of his characters: “And so he taught himself to regard the old man as a robber and himself as a victim. Who among us is there that does not teach himself the same lesson?”

As this suggests, the last laugh may belong to the Jews. One of the characters in Orley Farm (1861) is a ferociously capable solicitor, Solomon Aram, known for successfully defending the guilty. Trollope has two barristers discuss the wisdom of hiring him to defend the sympathetic will-forger Lady Mason:

“By-the-by, who is her attorney? In such a case as that you couldn’t have a better man than old Solomon Aram. But Solomon Aram is too far east from you, I suppose?”

“Isn’t he a Jew?”

“Upon my word I don’t know. He’s an attorney, and that’s enough for me.”

Here the work a man does defines him more than his family background—and in writing novels, as in practicing law, it’s the results that make a man’s name. As Trollope says elsewhere in the novel about Aram:

When one knew that he was a Jew one saw that he was a Jew; but in the absence of such previous knowledge he might have been taken for as good a Christian as any other attorney.

As An Autobiography makes clear, the young Trollope had come close to falling off the class ladder into the vast sea of hair-oil-using, false-jewel-wearing, tailorish non-gentlefolk himself. For Trollope, Jews stand outside the inherited social order, creating themselves by their work—much as he did, and as he was half-ashamed, half-proud of doing.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Ann Marlowe, a visiting fellow at the Hudson Institute, is a writer and financial investigator in New York. She is the author of How to Stop Time. Her Twitter feed is at @annmarlowe.

Ann Marlowe, a visiting fellow at the Hudson Institute, is a writer and financial investigator in New York. She is the author of How to Stop Time. Her Twitter feed is at @annmarlowe.