Archive Fever

Why a growing number of today’s young Jewish fiction writers—including two of the finalists for the Sami Rohr Prize being awarded tonight—are grounding their novels in scholarly research

Since when did multilingual archival research become a required skill for young Jewish novelists?

Consider three: Austin Ratner, Julie Orringer, and Sara Houghteling, all of whom have recently won awards for emerging Jewish authors. Ratner’s The Jump Artist, which will receive the $100,000 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature tonight,draws from letters, local newspaper accounts, and medical reports from a 1928 trial in Innsbruck, Austria. Orringer’s The Invisible Bridgewon the Edward Lewis Wallant award and was a finalist for the Rohr prize; it recreates the Munkaszolgálat newsletters produced by inmates of the Hungarian forced labor brigades in the 1940s. Houghteling’s Pictures at an Exhibition won the Wallant and Hadassah’s Harold U. Ribalow Prize andserves up details from Rose Valland’s Le front de l’art, published in Paris in 1961.

None of these sources are available in English. The authors, or research assistants, read them in the original. So, if one wants to know about Philippe Halsman’s trial, or the comic stylings of Hungarian forced laborers, or an insider’s view of the Nazis’ looting of the Louvre, the most widely accessible resources in English are these novels, notwithstanding the fact that they’re works of fiction.

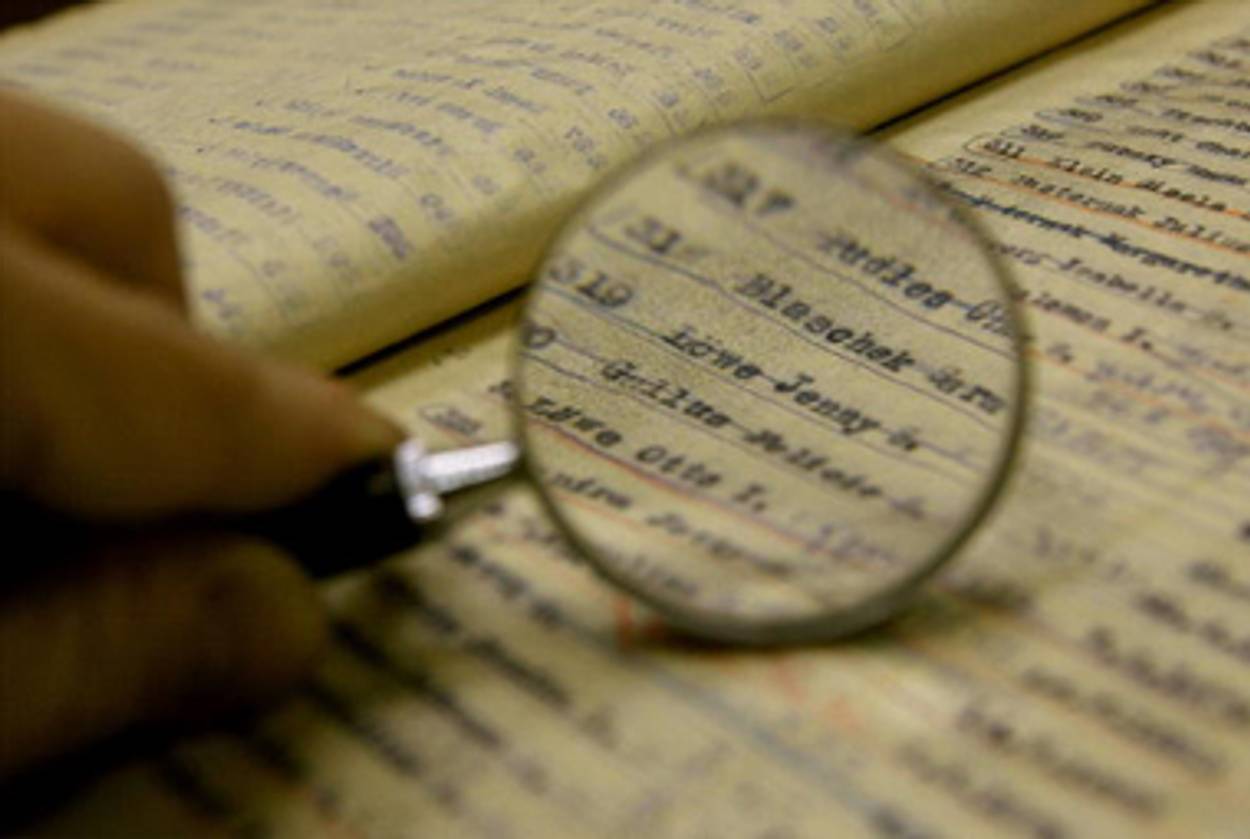

Jewish novelists have always drawn from history, whether it’s Isaac Bashevis Singer imagining the 17th century or Howard Fast’s vision of the Maccabees. Typically, though, they have availed themselves of published sources to construct their historical accounts, and they have tended to downplay the research itself, eschewing endnotes and other back matter. In a sense, Orringer’s novel—a dramatization of her grandfather’s life in the 1930s and 1940s—couldn’t be more conventional as historical fiction; but what’s unusual is the time she devoted to examining “artifacts and documents” at research institutes in D.C., Paris, and Budapest, like the National Hungarian Jewish Archives. What does it mean that this latest group of prize-winning novelists insists on doing historical research themselves, committing to more translation of foreign language texts and more digging through the archives than some of our popular historians do, and that they let their readers know about it?

In a recent essay, the three judges of the Wallant award survey the books they have considered in recent years and remark upon this phenomenon, declaring that “at no time before have Jewish writers in America turned so uniformly to history.” They suggest that this vogue for the “researched novel”—the sort of fiction written by Ratner, Orringer, and Houghteling—might be attributed to the impact of W. G. Sebald’s generically hybrid books and to a growing fascination with the construction and transmission of historical narratives among a generation of Jews with ever more attenuated connections to the events of the Holocaust.

More pessimistically, this archival work could be understood as part of a broader turn, by writers including Orringer, Nathan Englander, and Michael Chabon, from telling contemporary American stories to miring themselves in history. A cynic would say that this development reflects the feeling among young American Jews that there is nothing poignant about their lives. As William Deresiewicz phrased this in a review of Chabon and Englander in The Nation,“The most visible of the current generation of self-consciously Jewish novelists appear to be avoiding their own experience because their own experience just seems too boring. What is there to say about it? Better to write about a time or place where there was more at stake.”

Both of these arguments have merits, but the specifically archival character of these most recent prize-winners suggests another vector of influence: the positioning of creative writers within the university and on academic payrolls. Mark McGurl’s The Program Era,the book of the moment among scholars of contemporary American literature, points out how powerfully the situation of writers in America has changed in recent decades thanks to the explosive proliferation of MFA programs in creative writing. McGurl moves beyond potted debates as to whether working toward an MFA is an enabling aspect of a budding literary career or a homogenizing waste of money. (That’s one of those impossible questions that has as many answers as there are students and alumni of MFA programs.) Instead, he simply remarks upon how massive creative writing has become; with over 300 degree-granting programs and more than 25,000 members of the Associated Writing Programs (the organization for faculty members in the field of creative writing), creative writing in the academy, which pays full-time salaries and benefits to hundreds of novelists and poets, is “the largest system of literary patronage for living writers the world has ever seen.” Having made that point, McGurl then explores what effects this development has produced in the fiction written by the authors who operate within that system’s sphere of influence.

There can be no debate as to whether Ratner, Orringer, and Houghteling are products of McGurl’s program era. In fact, they’re products of a couple of the same individual institutions. Ratner received his undergraduate degree from the University of Michigan, Houghteling got her MFA there, and Orringer served there as a visiting professor. Ratner and Orringer both received MFAs from Iowa, while Orringer and Houghteling have also done time at Cornell, Stanford, and Harvard.

Of course, attending a specific school, or an MFA program in general, does not dictate a novelist’s methods or subjects. And it should be noted, as McGurl does, that one of the most consistent and typical products of the MFA system has been the standard collection of contemporary, semi-autobiographical short stories, like Orringer’s How to Breathe Underwater, that requires very little research into anything but one’s own navel. Still, as McGurl suggests, it cannot be entirely coincidental when some contemporary creative writers begin to resemble the literary scholars with whom they share their departments. And it seems plausible to suggest that movements in literary scholarship like New Historicism and history of the book, both of which emphasize archival research and have exerted pervasive influence over the study of American literature in English departments in the past few decades, might have helped to nudge a few creative writers toward the archive.

What concrete form could this institutional influence take? Well, cash. Michigan’s MFA students apply for research grants that allow them to travel abroad or consult archives. Why wouldn’t a student like Houghteling want to write fiction set in, say, France, if a fellowship were forthcoming that would fly her to Paris gratis and cover her croissants? Joseph Skibell’s A Curable Romantic, another prize-winner—it’s tonight’s $25,000 runner-up for the Rohr Prize—mashes up historical fiction and magical realism and includes lengthy passages translated from Esperanto, as well as some snippets in untransliterated Hebrew and Yiddish. Among his other supporters, Skibell thanks “the University Research Committee of Emory University,” where he serves as associate professor of Creative Writing/English. Again, the availability of research grants does not force novelists to translate foreign languages or to compile bibliographies of over a hundred sources in three languages (as scholars of American literature now tend to do), but obviously the possibility of financial support provides a substantial incentive for undertaking such projects.

It might be objected that Ratner and Houghteling aren’t currently academics; even Orringer only teaches as an adjunct these days. But it’s not just academicians who are affected by the institutionalization of creative writing, nor, for that matter, just recently “emerging writers.” Philip Roth, perhaps the least-emerging novelist in the universe, retired from teaching Comp Lit at the University of Pennsylvania almost two decades ago. Yet his most recent novels lean more heavily on research, or at least cite sources more insistently, than he has ever before in his career: his most recent novel, Nemesis, acknowledges 12 specific books from which he has “drawn information,” and The Plot Against America has a list of sources (for its postscript, granted) almost two pages long.

Whether or not a contemporary writer is formally employed by a creative writing program, McGurl insists, she cannot entirely escape what another critic has dubbed the “culture of the school.” Obviously not all young Jewish novelists have been rushing to visit manuscript collections—prizewinners like Ratner, Orringer, Houghteling, and Skibell are by definition exceptional, to some degree, in their literary practices—but doing so has begun to seem normal. The academy asserts its influence over fiction subtly but unmistakably: We see it in the lengthening of novels’ acknowledgments, the proliferation of bibliographies for fiction, and the citations of archival and multilingual research.

The archival turn exemplified by these recent novelists may have less to do with Sebald’s influence or with the blandness of contemporary Jewish life in the United States, then, and more with the status of literature in our culture. A literary novel is much more likely to be a credential for tenure these days than a popular entertainment, and some of our novelists—whether formally employed by universities or just having been educated by them—increasingly resemble our academic scholars. Whether or not this is salutary, and whether or not we like it, the archival turn reflects how our authors get paid, and if this current crop of emerging Jewish novelists is any indication, some get paid to teach us Jewish history.

Josh Lambert (@joshnlambert), a Tablet Magazine contributing editor and comedy columnist, is the academic director of the Yiddish Book Center, Visiting Assistant Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and author most recently of Unclean Lips: Obscenity, Jews, and American Culture.

Josh Lambert (@joshnlambert), a Tablet Magazine contributing editor and comedy columnist, is the academic director of the Yiddish Book Center, Visiting Assistant Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and author most recently ofUnclean Lips: Obscenity, Jews, and American Culture.