The Harvard Jesus Hoax

Ariel Sabar, in ‘Veritas,’ turns the true story of an academic con into a gripping thriller starring an overzealous feminist history prof, a wily forger, and Jesus’ wife

One day in July 2010 Karen King, Hollis Professor at the Harvard Divinity School, received an odd email from a stranger. The man was a manuscript collector, and he had some papyrus fragments he thought she might be interested in. One intriguing scrap of papyrus read:

… not to me. My mother gave me life …

… The disciples said to Jesus, …

… deny. Mary is (not?) worthy of it …

… Jesus said to them, My wife …

… She is able to be my disciple …

… Let wicked people swell up …

… As for me, I dwell with her in order to …

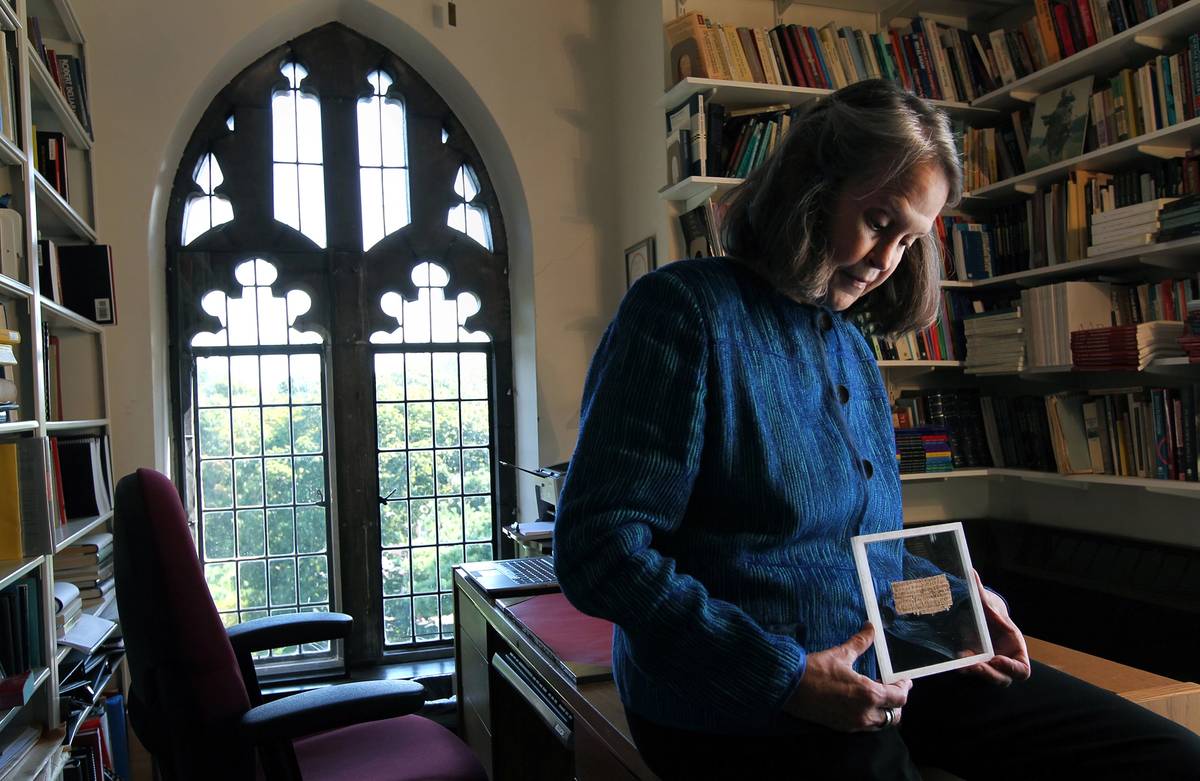

It took King over a year to respond positively to her email correspondent, but when she did, she fell hard. She started calling Coptic Papyrus 02-11 the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife. King told television interviewers that the business-card-size manuscript could overturn 2,000 years of Christian doctrine, finally granting women their rightful place in the Church. The fragment mentioned Mary, and King suggested this could be Mary Magdalene, whose relationship with Jesus was the stuff of Dan Brown’s pop bestseller The Da Vinci Code, published eight years earlier. Maybe Brown’s fantastically successful potboiler had it right, and Jesus and Mary were married.

The fragment’s Jesus was perfectly geared to appeal to a Christian feminist scholar like King. The Son of God turned out to be a married man who praised his wife as his true disciple, and honored his mother as well (“my mother gave me life”). This secret Gospel, the excited King thought, would have made the early Church quake in its boots. The second-century Church fathers said Jesus was celibate, unlike other first-century rabbis, and declared that only men could preach his word. Though the Jesus’ Wife fragment couldn’t have been earlier than the fourth century, King suggested that it must be a copy of a second-century Greek original. Clearly, King thought, misogynist Church fathers like Clement of Alexandria must have been reacting against the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife, which predated them and therefore had greater authority. Here was astounding news: Jesus was a feminist, a fact fiercely repressed by Church patriarchy.

There was only one problem. The Jesus’ Wife fragment turned out to be a crude fake. King got taken for a ride by a swindler named Walt Fritz, who ran a “hotwife” pornography business out of his Florida home. Fritz had studied enough Coptic to make a stab at a phony ancient papyrus, but the fragment’s grammatical blunders and the scribe’s clumsiness with the writing stylus should have alerted King that something was fishy. When experts eventually examined the Jesus’ Wife fragment, they pegged it as an obvious fugazi. Fritz has always officially denied forging the Jesus’ Wife papyrus, but the evidence against him is overwhelming.

In his scintillating new book Veritas, journalist Ariel Sabar, who exposed Fritz’s forgery for The Atlantic in 2016, shows step by step exactly how Fritz bamboozled King. It’s a suspenseful story, taking Sabar from Cambridge, Massachusetts, to South Florida to Germany, Fritz’s home country. Sabar, a tireless detective, delves deep into Fritz’s life story, including his stint as director of the Stasi Museum in Berlin, where he was suspected of pilfering memorabilia. Fritz was apparently raped by a priest as a boy, and that trauma strangely influenced his manuscript hoax. Other characters play a role as well, like Fritz’s wife, who performed in pornographic videos as Jenny Seemore and used her webpage to hint at Gnostic motifs derived from the faked papyrus.

Veritas is a gripping thriller, and a perfect beach read. I don’t want to spoil it, so I won’t reveal the possible involvement of Harvard’s administrators in the Jesus’ Wife fiasco. Suffice it to say that Harvard, not just King, fell for Fritz’s tantalizing papyrus. Sabar’s book adds to one’s sense that the ivory tower is tottering, with professors peddling wishful thinking that masquerades as scholarship, and letting their progressive values freely rewrite history.

Sabar is a master storyteller, adept at showing how the Jesus’ Wife papyrus became a litmus test for the gullible King. Most forgers would shy away from showing their work to a top scholar like King for fear of being caught. But Fritz headed straight for her. She was his perfect target.

Though Fritz told King he was “clueless,” he was in fact an expert at appealing to King’s feminist sensibility, and he tailored his fragment expressly for her. With an old school con man’s flourish, he pretended he didn’t quite know what the fragment meant or how much it might be worth. As Douglas Maurer points out in his classic The Big Con, con artistry requires getting your customer, the mark, to bite without your prompting. Though Walt Fritz told an elaborate series of lies about the papyrus fragment’s provenance, forging letters from several dead experts in the field, he never claimed it was authentic. Fritz was a sloppy forger, but it didn’t matter. King swallowed the bait anyway.

She had been waiting her whole adult life for such a discovery. King made her name as a scholar of the Gnostic Gospels condemned by the early Church. She particularly loved the Gospel of Mary, discovered in 1896, in which Jesus’ disciples receive guidance from someone named Mary—an exceedingly common name in first-century Palestine but in this case, King argued, probably Mary Magdalene. Mary explains to the disciples Jesus’ Gnostic lesson about the soul’s solitary ascent. Astonished by her teaching, they conclude that Jesus “loved her more than us.”

King loaded a lot of feminist messaging onto a single brief text, the Gospel of Mary. She needed the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife to nail down her theory that Mary Magdalene was Jesus’ chief disciple, a fact covered up for 2,000 years by misogynist Christian hierarchs.

When Fritz approached her with his tantalizing piece of papyrus, King was in the middle of a careerlong effort to revise Gnosticism by turning it in a feminist direction. She had to sideline the Gnostics’ rejection of the world, which they saw as an inferior creation designed to fool the ignorant. For the Gnostics, salvation came from what Sabar calls “personal knowledge, or gnosis, of the divine.” Gnostic secret knowledge could save you from what you might call the Matrix, the dark, destructive cosmos that most people take for reality.

The Church was not impressed by Gnostic doctrine. To one early bishop the Gnostics were “deluded people” who “assault us like a swarm of insects, infecting us with diseases, smelly eruptions, and sores.” But in the 20th century the Gnostics’ stock rose appreciably. In 1945 a peasant named Mohammad al-Samman stumbled on a treasure trove of Gnostic manuscripts in a buried jar near Nag Hammadi, Egypt. They were stunning, explosive texts, full of enigmatic sublimity. One scripture, called “Thunder, Perfect Mind,” proclaimed, “I am knowledge and ignorance. I am shame and boldness. I am shameless; I am ashamed. I am strength and I am fear. I am war and peace. Give heed to me … do not be afraid of my power.” The German Jewish philosopher Hans Jonas compared the Gnostics to Heidegger, claiming they had uncanny resonance for the age of existentialism. Gnosticism, Jonas thought, portrayed the isolated, and illuminated, self thrown into a dark world. Harold Bloom applied Jonas’ version of Gnosticism to writers like Emerson and Melville, and even claimed to be a Gnostic himself. One current scholar has praised Gnosticism as a “New Age,” “countercultural” spirituality reflected in everything from Superman comics to, needless to say, The Matrix.

King disagreed with Jonas. Instead of championing a stranded visionary selfhood, her Gnostics were socially oriented. And they were pro-woman. King asserted that the Gospel of Mary was a “straightforward and convincing argument … for the legitimacy of women’s leadership.” Mary Magdalene was not a forlorn ex-prostitute, as the Church claimed, but Jesus’ central disciple and companion. Here was up-to-the-minute feminism, strikingly embodied in a second-century CE text.

Some of King’s work, though prized by Harvard as historical scholarship, was actually anachronistic fantasy. Jesus’ “my wife,” she announced in a documentary film about the papyrus, “allows us to recapture the pleasures of sexuality, the joyfulness and the beauties of human intimate relations.” The known Gospels give no evidence at all that Jesus valued “the pleasures of sexuality,” but this was no obstacle for King’s revisionism.

King offered Midrash, rather than scholarly proof that Jesus was a feminist who appreciated marital sexuality. There was simply no support for her view. If she had styled herself a free interpreter rather than a historian, that would be fair enough. Any religious tradition requires exactly King’s kind of rereading, adjusting an earlier text in the light of later needs. In Judaism, for instance, the Talmud radically revises the Torah. But King wanted to be more than just an interpreter. She claimed to have hard evidence that could change everything we thought about the Church.

Sabar’s judgment of King is harsh but accurate. “King wanted it both ways,” he writes. “She sought to expose the Church’s ‘facts’ as positions while promoting her own positions as facts.” He adds that “she demanded that people be ‘accountable’ to facts and history, though she herself believed in neither.”

Texts would mean what King wanted them to mean, so that a few enigmatic references to a figure named Mary were actually a celebration of the feminine principle. King combined such airy mythmaking with the claim that facts were on her side. That’s the recipe of conspiracy theorists, and so she cast her lot with the The Da Vinci Code, though she criticized Brown for failing to see Mary Magdalene as a spiritual leader. Still she praised The Da Vinci Code in a 2004 MSNBC interview for the way it showed “the enormous diversity of early Christianity.”

King’s target audience was the millions who up the ante on their pseudohistorical fantasies by adding one more fantasy: that it’s all true. Genuine religious interpreters acknowledge, instead, that the facts about Jesus are mostly lost in the darkness of time, and that when evidence is scarce our imagination steps in. Imagination can exert authority, too; and in religious tradition, it has to.

King’s repurposing of Jesus had a precursor. When King was an undergraduate at the University of Montana, Sabar writes, she “fell under the spell” of Robert W. Funk, a charismatic, publicity-seeking professor who referred to Jesus as a “party animal,” a “social deviant,” and “perhaps the first Jewish stand-up comic.” Funk founded the Jesus Seminar, a group of liberal theologians who announced in a 1993 bestseller that Jesus, rather than being celibate, probably “had a special relationship with at least one woman, Mary of Magdala.” King was a prominent member of the Jesus Seminar, and shared its goal of suggesting a relationship between Jesus and Mary, a decade before The Da Vinci Code and two decades before the Jesus’ Wife Gospel.

But King went further than her Jesus Seminar colleagues. No scholar had ever suggested that the Gnostic Gospel of Philip, another of King’s favorite texts, implied a marriage between Jesus and Mary Magdalene. Only Karen King and Dan Brown argued that it did.

After the papyrus had been revealed as a fake, King still stuck to her guns. In honor of the Harvard Divinity School’s bicentennial she gave a public lecture on the Church’s ancient “rhetoric of forgery,” when the Church fathers lambasted heretics as forgers, frauds, and sexually promiscuous—the implication was that she too was one of these victims of patriarchy. Here was a chutzpahdik maneuver. King gave no hint that she was at fault, nor did she even acknowledge that she had been bilked. Instead, she seemed to blame her critics.

The post-truth world had come to Harvard. King “called facts ‘little tyrants’ and accused people who put too much stock in them of ‘fact fundamentalism,’” Sabar reports. But King insisted for years that she had a handle on the facts, with the papyrus her key piece of evidence that Mary Magdalene was Jesus’ wife. In the end, the famous papyrus became fodder for comedians; Colbert and Jon Stewart piled on.

King was not the first to come a cropper when her pipe dream of the historical Jesus proved groundless. The Christian Gospels open the way for such futile questing after the hidden but real Jesus, both because Jesus is such an enigmatic figure and because he stresses his actual bodily presence. Since Christians believe in the actuality of Jesus, and yet such a long-ago truth (if that’s what it is) can never really be rediscovered, fact and fiction blend together, and fraudulent temptations beckon.

Karen King walked with Walt Fritz down the road of fraud, in perhaps the most spectacular case of scholarly wish-fulfillment since the Hitler Diaries. The result was a world-class embarrassment, and a reminder that it can be dangerous to insist that your progressive fantasy is God’s own truth.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.