Atomic Bombshell

New research uncovers a link between Freud’s inner circle and the Soviet atomic bomb

Novelists often engage in research to learn the background and provide verisimilitude for historical yarns, but we intended nothing of the kind when we began an inquiry into an espionage controversy that had raged since the 1980s. When Yale University Press commissioned our book Foxbats Over Dimona: The Soviets’ Nuclear Gamble in the Six-Day War, our editor Jonathan Brent suggested that we add a preface to outline the historical background of Russian involvement in the Middle East. While reviewing Soviet covert activity in Palestine under the British administration as revealed by recently emerged Russian sources, we found that it began sooner after the 1917 Revolution, was ascribed a higher priority, and included higher-ranking figures than we and other scholars had assumed.

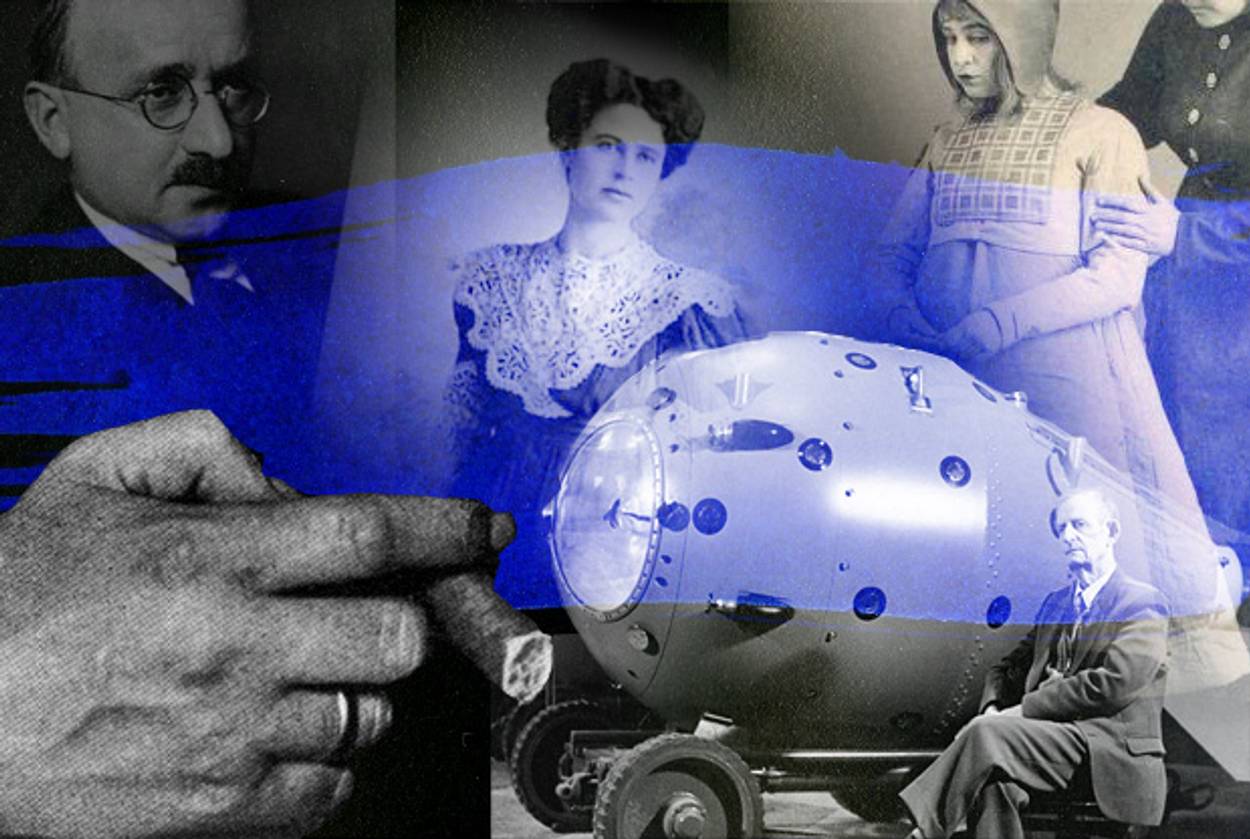

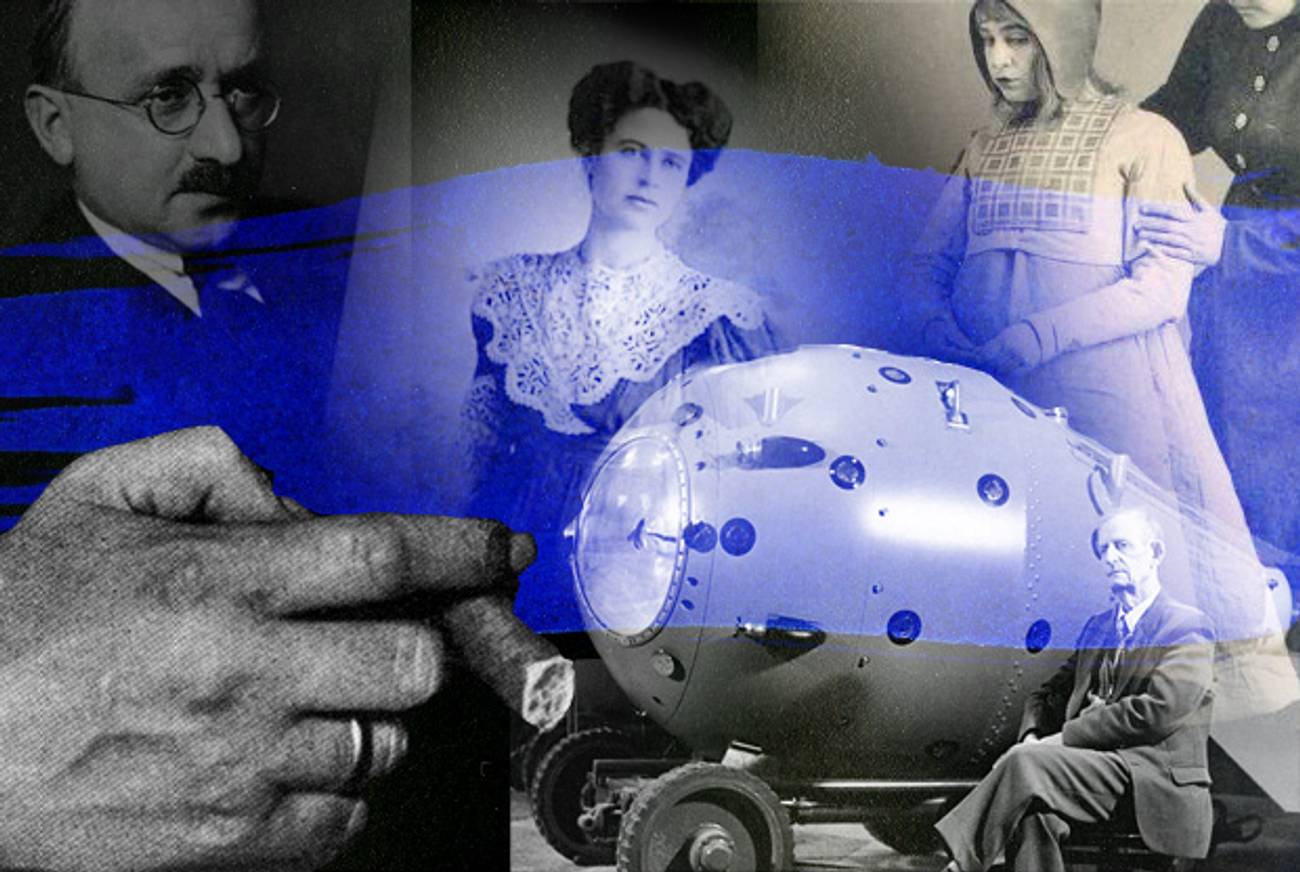

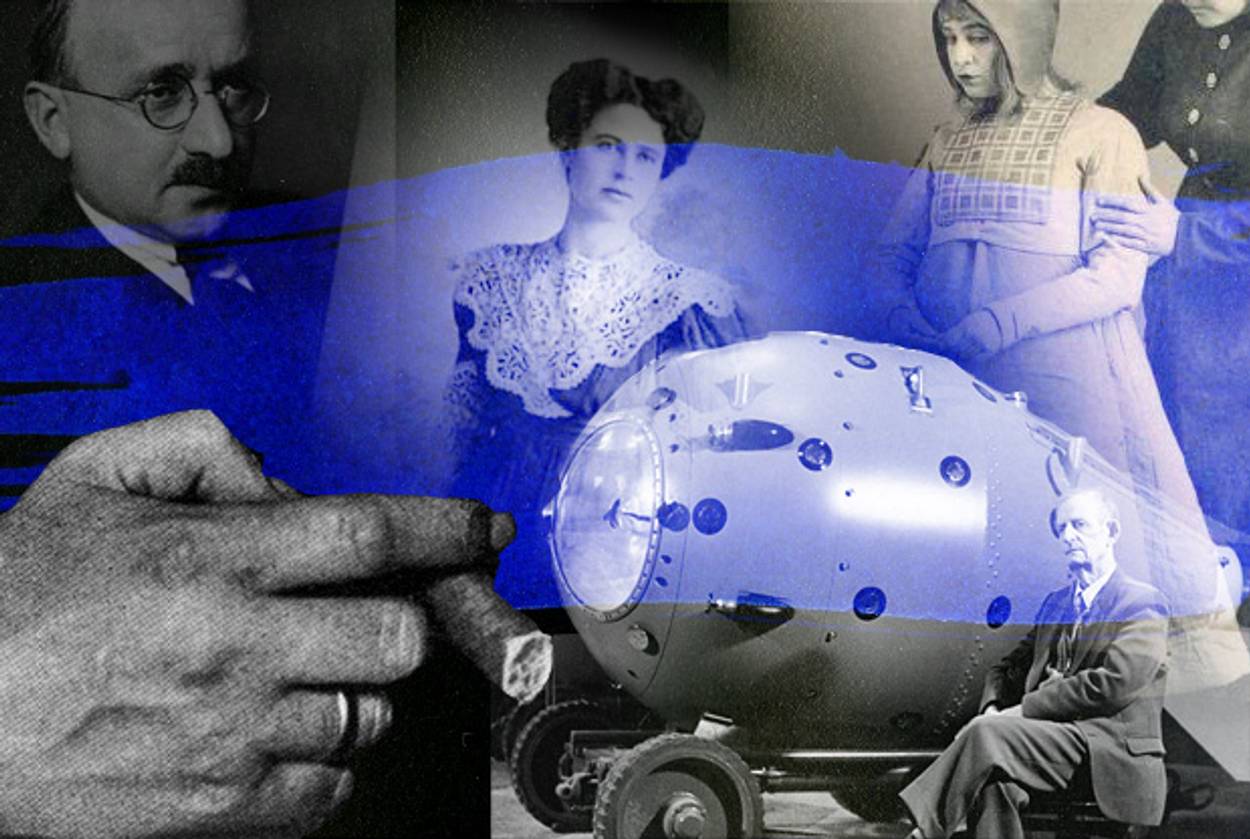

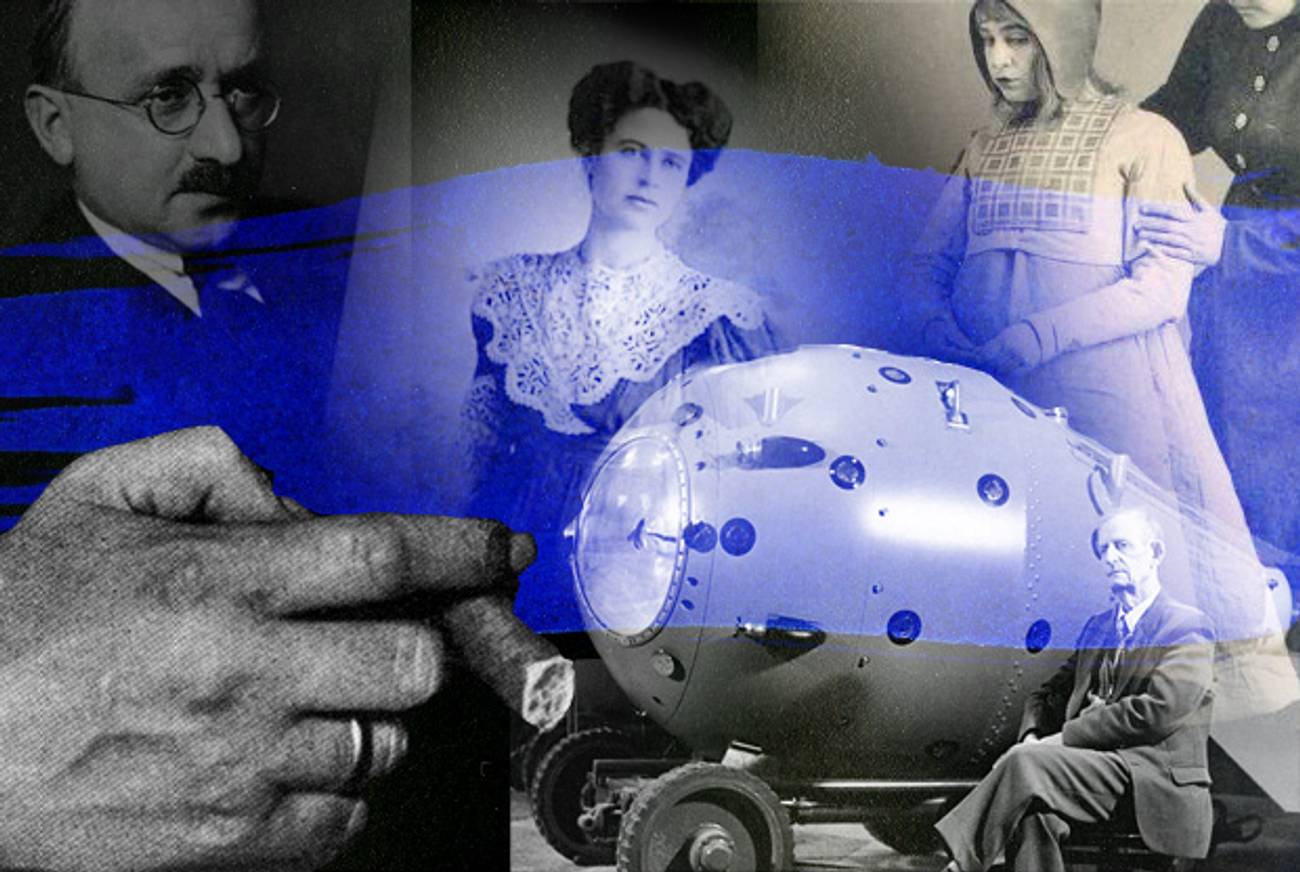

We were particularly intrigued by the allegations that Dr. Max Eitingon, an early student of Sigmund Freud and a financial sponsor of the early psychoanalytic movement, was also an agent of Soviet intelligence. The debate that erupted on this issue in 1988 in the New York Review of Books and New York Times Book Review, among others, focused mainly on Eitingon’s activities in the 1920s and early ’30s, when he endowed and directed the Psychoanalytic Institute and free clinic in Berlin. Because he was a Jew, the Nazis forced him out of his medical positions in 1933. Eitingon then chose to migrate to the remote backwater of Jerusalem—to the surprise of Freud and his other colleagues. There he founded and funded the first psychoanalytic institutions in what was to become Israel.

There is now at least a preponderance of circumstantial evidence that Eitingon did cooperate with Soviet secret agencies even after moving to Palestine—though he hardly qualified as one of “Stalin’s killerati,” as suggested by Stephen Schwartz in the essay that sparked the original debate. Rather, his contribution was more by way of relaying money and information and by making his sumptuous homes (first in Berlin, then in Jerusalem) available as safe houses for discreet meetings, lodging, and mail drops. Our investigation thus registered, at first, a moderate confirmation of the existing—interesting but hardly dramatic.

It was then that a brief reference drew our attention to Eitingon’s wife, Mirra. The espionage polemic hardly mentioned her at all; the vast psychoanalytic literature, which disdainfully dismissed the allegations against one of the movement’s pillars, held her in contempt. She was universally denigrated as pampered, intellectually lightweight, and a brake on her husband’s career—a misevaluation that originated with Freud himself. And since an erroneous rendering of her maiden name was copied from one study to the next, this character assassination (as we found it to be) could hardly be corrected, nor could the significance of her actual identity be detected.

However, though Freud belittled the Russian-born Mirra as a former “comedienne,” he did mention one accurate detail: that she had acted in Konstantin Stanislavsky’s celebrated Moscow Art Theater. This first aroused our doubts about her conventional description: The director’s famously demanding method could not be reconciled with physical or mental indolence. Such weakness certainly could not be attributed to the first Jewish actress to overcome the formidable legal and social restrictions in Tsarist Russia to play major roles on its premier stages—a distinction we now found that Mirra née Burovsky had achieved by 1908, a year before meeting Eitingon. By that time she had also racked up a life story that could fill a novel; a stage sobriquet, “Mirra Birens,” and two married names—both famous. She also gave birth to a son, Yuli Borisovich Khariton, who, 80 years later, when the collapse of the USSR lifted the veil of secrecy that surrounded his accomplishments, would gain world renown as “the father of the Soviet atomic bomb.”

As we researched further, what began to take shape was a story with an illustrious cast of characters, a complex plot line spanning disciplines from psychoanalysis through theater to nuclear physics, and a heroine so extraordinary that no author would have dared to invent her.

***

The capital for Eitingon’s philanthropies originated in his family’s lucrative international fur trade, which prospered thanks to a near monopoly on export of Soviet pelts that made it, through the 1920s, the largest private U.S. importer from the USSR and gave the Eitingons a strong motivation to cooperate with successive incarnations of Soviet intelligence. Another intriguing clue was the name of a leading chekist, Gen. Nahum, aka Leonid, Eitingon, who was responsible, among other exploits, for staging Trotsky’s assassination. The debate in 1988 over whether and how Gen. Eitingon was related to Max has since been resolved by his colleagues and descendants: The two men were cousins.

Little doubt now remains about the Eitingon clan’s collaboration with the Soviets—particularly by Max’s New York-based cousin (and his sometime brother-in-law) Motty, who shortly after claiming a dramatic escape from the Bolsheviks in 1918 was cutting million-dollar fur deals with them. Besides Motty’s support of pro-Soviet intellectuals, trade unions, and causes, his name has popped up in KGB documents that the journalist Alexander Vassiliev was allowed to copy in the chaotic days around the disintegration of the USSR.

Likewise, it is by now clearly established that Leonid Eitingon was assisted by the family firm—in New York and elsewhere—to set up his American spy ring. And our own examination of Max’s papers, as well as his record in Palestine in addition to Berlin, strongly bolstered his accusers’ exhibit A: At the 1938 Paris trial of the Russian singer Nadezhda Plevitskaya for the fatal abduction to Moscow of the “white” Gen. Yevgeny Miller, she fingered Max as her longtime patron even after he relocated to Palestine. The affair has inspired much fictionalized literary treatment, from Nabokov to Anatoly Rybakov. But the fact that Plevitskaya and her husband-accomplice Nikolai Skoblin were indeed recruited by the Soviets had been conclusively documented by the time we revisited the case.

A memorial book published after Yuli Khariton’s death in 1996 revealed that his nickname was Lusia—the hitherto mysterious signature on a letter in the Eitingon papers. It then emerged that 15 years after Mirra left Yuli with his father (the Constitutional-Democrat journalist Boris Khariton) in St.Petersburg, he twice visited his mother and stepfather in Berlin. Mother and son both so assiduously concealed these meetings, and their relationship, that the facts emerged only in his posthumously published memoir. Khariton’s survival and progress during Stalin’s purges were so remarkable for someone with his background that we had to conclude it was one of the factors in Eitingon’s modus vivendi with the Soviets—in which Mirra played a leading real-life role. The Yuli Khariton factor added both a strong motive and a mitigating circumstance for Max Eitingon’s cooperation with the Soviets: His letters show he worshipped Mirra and did all he could to help and protect her son—while suffering great anguish that he never had children of his own.

This new and moving human aspect of the affair helped to stir the interest of Glenda Abramson, the Oxford professor who edits Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, when we submitted an essay on our preliminary findings. As scholarly journal publications take time “in the pipeline,” and we were now consumed in further exploring the story, the present article is a progress report on our research—and we hope readers will forgive the almost forensic detail that has become our stock in trade.

Some of the new evidence we have found is directly connected with our reassessment of the “espionage” debate. One example is the prominence of figures connected with the psychoanalytic movement in the Soviet establishment during the peak years of Max’s activity in Berlin. We knew that Soviet Russia’s first envoy to Germany, Adolf Yoffe, was a patient and student of Alfred Adler while the latter was still a member of Freud’s circle. His successor, Viktor Kopp, was the vice-president of the Soviet Psychoanalytic Association (which enjoyed official aegis as long as their mentor, Freud’s admirer Trotsky, was in power). Our hypothesis that these professional acquaintances provided Max—and the Eitingons’ family enterprise—with a direct link to Moscow has now been borne out, offering a fascinating window into the links between two revolutionary movements of the 1920s—Soviet communism and psychoanalysis.

The former commissar for finances of the short-lived Hungarian Soviet republic, Jenö Varga, was an early supporter, then a member, of the Hungarian Psychoanalytic Association. After the defeat of the Hungarian revolution, Varga was interned in Austria, and upon his release he attended seminars in Freud’s Vienna residence before being transferred to Russia. In 1923, after being posted to the Russian commercial mission in Berlin, he resumed his connection with Freud’s circle via Eitingon’s Institute. Freud’s Secret Committee was soon notified (in a document recently published by the Freudian scholar Christfried Tögel) that Varga would “enable correspondence with Moscow by courier,” a connection that was then next to impossible by other means. It might be argued that this link was used for psychoanalytic business alone; we doubt it.

A lot of what we’ve discovered rounds out the Eitingons’ characters and their place at center stage of cultural as well as political history, ostensibly apart from the issue of Soviet intelligence. But more often than not, their double lives are intertwined. Take, for instance, Mirra’s first marriage. We originally knew about it only from the 1943 Yiddish memoirs of the author and playwright Osip Dymov, who launched Mirra’s stage career. An affair between them was widely rumored and became a scandal in 1907 St. Petersburg when her second husband, Boris Khariton, fired four pistol rounds at Dymov (though a distinguished journalist, Khariton was not a marksman: He missed all four times). The incident provided the plot for Dymov’s best-known play, Nju, and later a major silent film. Describing it, he wrote that “the young lady who played such a serious role in my destiny” had, before wedding Khariton, fled a marriage to a scion of the Brodsky dynasty—the sugar magnates of imperial Russia—to whom she had borne a son. But Dymov didn’t actually name Mirra (to protect her reputation, as he explained), and there was no other evidence of this marriage and child.

So, imagine our delight when a few weeks ago we found conclusive proof that this child, Viktor Brodsky, was a high-school student in Baku in 1913 and in affectionate contact with his mother, who was by then already in Berlin. Freud heard at some point that Mirra had had two children, the first of whom was killed by the Bolsheviks. But Freud also heard that her second son, whom we now know was Yuli Khariton, was “in Siberia,” and untraceable—which was incorrect and possibly resulted from the Eitingon’s own efforts to obscure their link.

We’re now trying to establish Viktor’s fate, which besides adding to the drama might have a lot to do with the espionage inquiry. Recently, we discovered that a Jewish “artist” named Viktor Brodsky, of the right age, who gave his birthplace as Yekaterinodar—Mirra’s hometown—arrived at Ellis Island in 1923, with a group of defeated “white” Russians who had escaped to Constantinople. There were only a few hundred Jews in Yekaterinodar at the time, and for two to be born the same year with the same name seems highly unlikely. He then changed his surname to Piatakoff—the name of a prominent Bolshevik, and hardly a convenient name to assume at random when applying for naturalization, which he successfully did. Viktor Piatakoff, who described himself as a textile designer in New York, lived to age 92—just like his apparent half-brother Yuli Khariton. But that’s all we’ve been able to find out about Viktor so far. If Tablet readers can help, we’ll be much obliged.

Another facet that we have just begun to explore is the Eitingons’ close friendship with Arnold Zweig, the German-Jewish writer who found refuge in Palestine but then returned to East Germany in 1949. Zweig, whose finances were precarious until he began to receive royalties from Moscow, often enjoyed the Eitingons’ hospitality and published glowing eulogies of both of them. His last novel, set in the Middle East during World War II, Traum ist teuer (“dreaming is costly”—never translated into English), features a saintly psychiatrist, Manfred Jacobs, who is an obvious lionization of Max Eitingon, as well as a pampered Mrs. Jacobs who resembles the negative stereotype of Mirra.

Arnold Zweig engaged in overt pro-Soviet activity such as publishing a periodical, Orient, and—after the Nazi onslaught on the USSR—organizing the “V[ictory] League to support the Soviet Union’s Struggle against Fascism.” Max Eitingon—though already unwell and with barely a year yet to live—was enlisted to become the president of the Jerusalem chapter (the organization’s original charter was drafted by Martin Buber). Zweig also had clandestine links with the Moscow-based, paramilitary Nationalkommittee Freies Deutschland, and in later years confirmed that he had conducted such distinctly intelligence-related activities as spreading Soviet information materials among German POW’s in Egypt.

In Traum ist teuer, Zweig describes a hero of the Communist Greek resistance who seeks shelter in Palestine. A document in the files of the Haganah’s anti-Communist department connects the harboring of just such a fugitive with Hava Rund—the Jerusalem Party cadre who claimed to the Israeli writer Haim Be’er, after the 1988 Eitingon controversy, that she was the liaison to Eitingon for money transfers that he delivered to the party “from the day he arrived” in Palestine. And most remarkably, in another letter we found in Berlin, Arnold suggested to Mirra—in 1945, after Max’s death—that she might let rooms in their house to officials of a Soviet political mission that was about to open in Jerusalem. Nothing was publicly announced at the time about an intended Soviet office, and none ever opened; the Soviets in question would have come under cover. Zweig, then, was privy to confidential Soviet information and trusted Mirra with it.

An even more suggestive example of Max and Mirra’s place at the center of pre-Israeli intellectual life is their complex relationship with the writer and Nobel Prize laureate S.J. (Shai) Agnon, and especially his wife Esther (better known as “Estherlein” from their published letters). We couldn’t help noticing that after Max’s father Chaim Eitingon was expelled with other Jewish merchants from Moscow in 1891—a trauma that we believe left a lasting mark on his then 10-year-old son Max—he took up at least formal domicile in Buczacz, Galicia, and thus gained Austro-Hungarian citizenship for his family. They soon established themselves in Leipzig, but Max’s MD thesis in 1909 still identifies him “aus Buczacz.” Freud’s father also happened to hail from there, but the town’s most famous native and chronicler is Agnon. It soon transpired that his maternal grandfather was, like Chaim Eitingon, a fur trader who took Shai’s father into the business, and it’s pretty certain that this common trade explains the Eitingons’ choice of this particular shtetl, as well as an origin of Max’s acquaintance with the Agnons.

For a memorial volume on Max Eitingon, Agnon (who attended Max’s funeral) contributed a short story, “Another Tallith,” dedicated to Max’s Hebrew name, Reb Mordechai Halevy, which was also the name of Agnon’s father. It relates a dream, exemplifying Agnon’s interest in this angle of Freudianism. There’s a typescript of it in Eitingon’s papers, along with one of a rare, yet-unpublished fragment, also about a dream—which indicates that Max was shown the stories in his lifetime, probably by Esther, who used to type her husband’s manuscripts. Unlike Max, who gave Mirra liberty to pursue her interests, Agnon stifled Esther’s, and their marriage was rocky. According to the historian Avner Falk, she fled their home several times and sought Max’s professional help throughout his 10 years in Jerusalem.

A final, tragic note is also among our recent discoveries in Zweig’s papers. In 1947, four years after Max died, Mirra left Jerusalem to care for her ailing sister in Paris—ostensibly confirming the widespread version that the Eitingons had come to Palestine over her objections. We, however, had found several indications that her Zionism had always been at least as enthusiastic as his. This was now corroborated when it emerged that Mirra had already booked her return passage to Palestine, even though she now had no family or property there—but she died two days before the ship sailed. Unnamed friends (we suspect it was Princess Marie Bonaparte) flew her casket back to Jerusalem, where her burial, next to Max, was among the last Jewish funerals on the Mount of Olives before it was cut off by the outbreak of Israel’s War of Independence.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Isabella Ginor and Gideon Remez are research fellows at the Truman Institute of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Their paper “Her Son, the Atomic Scientist: Mirra Birens, Yuli Khariton, and Max Eitingon’s Services for the Soviets” appeared in the Journal of Modern Jewish Studies.

Isabella Ginor and Gideon Remez are research fellows at the Truman Institute of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Their paper “Her Son, the Atomic Scientist: Mirra Birens, Yuli Khariton, and Max Eitingon’s Services for the Soviets” appeared in the Journal of Modern Jewish Studies.