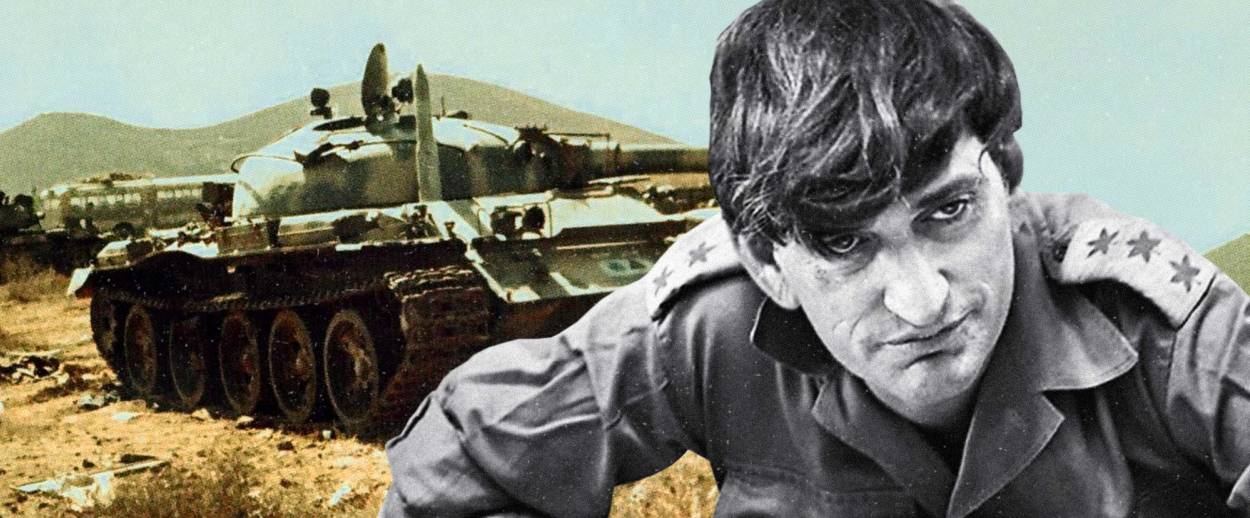

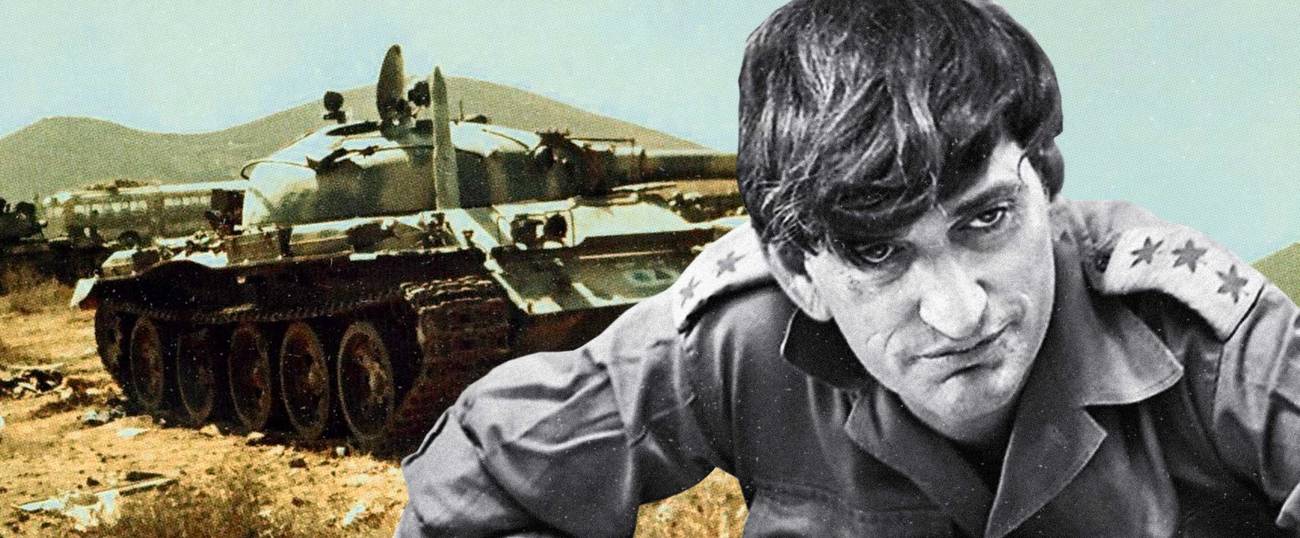

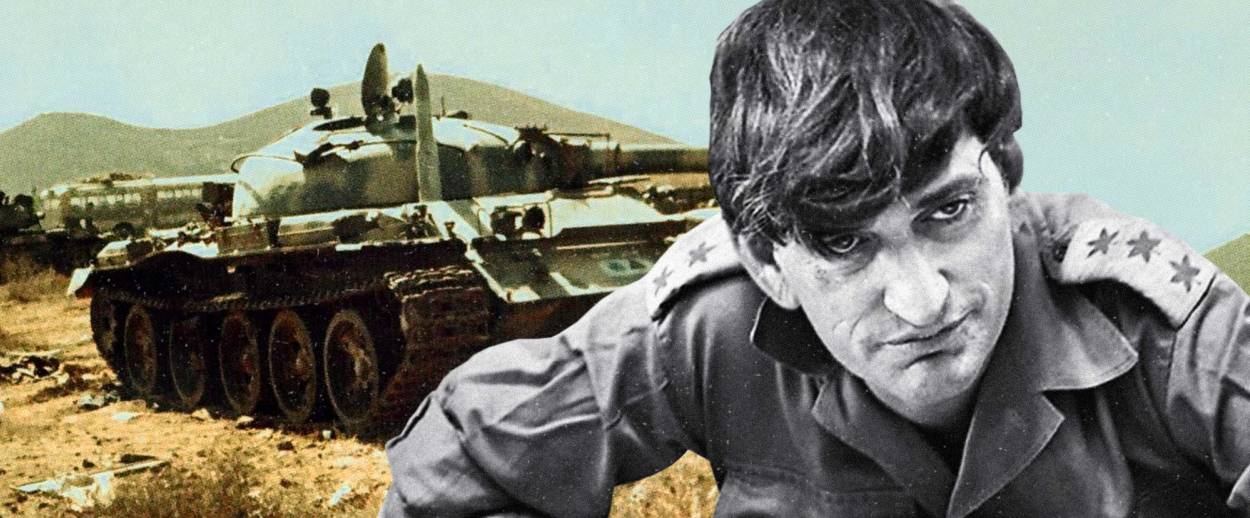

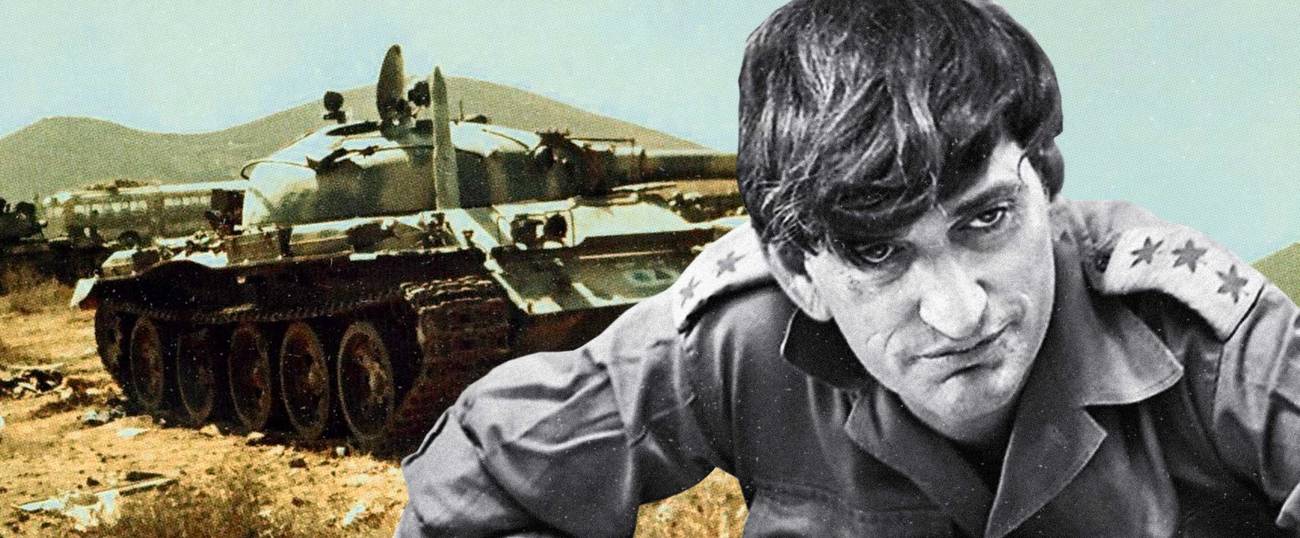

The War for the Golan Heights

Remembering the dead lost under Avigdor Ben-Gal’s pivotal battle to hold the Syrian army on the Golan Heights in the 1973 Yom Kippur War

Col. Avigdor Ben-Gal drove along the cease-fire line in his halftrack and scanned the Syrian plain. There was a large army out there, much larger than he had ever seen the Syrians deploy. Camouflage netting cloaked hundreds of tanks and artillery pieces spread over the terrain like stacks of hay at harvest time. Nothing was stirring. It was noon on Yom Kippur, 1973.

Ben-Gal, commander of the Seventh Armored Brigade, had for the past 10 days been dispatching units piecemeal up to the Golan from their training grounds in Sinai as the General Staff ratcheted up its assessment of the perceived threat from Syria. The brigade’s last tanks were at this moment making the steep ascent from the Jordan River.

At the sound of chirping Ben-Gal raised his head and saw birds on a nearby tree. There was nothing unusual about the birds singing. What was odd was that he could hear them. The unnatural stillness seemed final confirmation that war was imminent.

Two weeks earlier, at a meeting of the Israeli General Staff in Tel Aviv, Maj. Gen. Yitzhak Hofi was scheduled to be the first to comment on the main subject on the agenda, the proposed acquisition of the new American F-15s. “There’s something else I want to talk about first,” said Hofi, commander of the Northern Front. The situation along the Golan cease-fire line, he declared, had become “very serious”; the deployment of the Syrian forces permitted them to strike without warning.

His colleagues knew well that opposite the understrength Israeli division guarding the Golan were three Syrian divisions at full battle strength. Hofi wanted to draw his colleagues’ attention to a new element: the forward positioning of the latest Soviet anti-aircraft missile, the SAM-6. The Israeli Air Force (IAF), which had dealt with earlier SAM versions, had not yet found a solution for the SAM-6. The IAF had stopped overflying the Golan and even the upper Galilee, inside Israel, because of the missile’s long reach. Only low-flying planes like crop dusters were permitted to fly over the area. This meant, Hofi said, that he would not have air support in the event of a surprise Syrian attack. Without air support, it was questionable if he could hold the Golan. Having made his point, Hofi went on to give his opinion about the F-15s.

The discussion about the new planes proceeded around the table without anyone commenting on Hofi’s remarks, as if a surprise Syrian attack was too unlikely a prospect to merit serious discussion. It was the consensus that Syria would not go to war without Egypt and there had been no sign that Egypt was preparing for war. But Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, sitting in on the meeting, brought the generals back to Hofi’s warning. “The General Staff can’t let Khaka’s [Hofi’s nickname] remarks pass without comment,” he said. “Either his scenario doesn’t hold water or it does. If it does, we need a plan for dealing with it.”

The chief of staff, Lt. Gen. David Elazar, downplayed Dayan’s concern. “I don’t accept that the Syrians can conquer the Golan.” If Damascus was planning war, he said, intelligence would certainly pick it up in time to mobilize the reserves. If war broke out, Elazar said, the air force would provide the ground forces close support and pay whatever price was necessary.

After the General Staff meeting, Elazar ordered two companies from the Seventh Armored Brigade in Sinai sent north to reinforce the 77 tanks presently on the heights and thereby placate Dayan. “We’ll have 100 tanks against the Syrians’ 800,” he said. “That should be enough.”

Israel’s stunning victory in the Six-Day War had shattered three Arab armies but it also inflicted serious collateral damage to Israel itself by fueling unbridled self-confidence. Even cautious leaders were swept up by hubris. “Arab soldiers lack the characteristics necessary for modern war,” said Gen. Haim Bar-Lev, who had preceded Elazar as chief of staff. These attributes, he said, included adaptability, technical competence, a high level of intelligence, “and, above all, the ability to see events realistically and speak truth, even when it is difficult and bitter.”

Echoing that sentiment was Gen. Eli Zeira, chief of military intelligence. A former commander of the elite paratroop brigade, with a stint as military attaché in Washington, Zeira was highly regarded by Dayan and was considered a safe bet to become a future chief of staff. Some, however, were put off by his self-assurance. A paratroop colonel who heard Zeira for the first time addressing a closed forum told a colleague he would have preferred an intelligence chief less certain about things. Zeira was convinced that Egypt and Syria, whatever their threats or deployments, would not go to war because they understood that they risked a replay of the Six-Day War. Earlier in the year, numerous reports were received that Egypt and Syria were planning a surprise attack. The reports were taken seriously by Dayan and Elazar who ordered extensive defensive steps but Zeira dismissed the threat as empty. When the tension dissipated without incident after a few weeks, his already high reputation soared; the chief of staff would henceforth be loath to challenge Zeira’s assessments.( Zeira, it would turn out, had been right for the wrong reasons; Syria wanted a postponement of the planned attack only because it was awaiting advanced weaponry from the Soviet Union.)

In September, tensions rose once more. Eleven separate warnings of war were received during the month. One source was none other than Jordan’s King Hussein who arrived one night by helicopter for a secret meeting with Prime Minister Golda Meir in a Mossad safe house outside Tel Aviv. He warned of an imminent two-front war but Zeira was unimpressed. His standard situation assessment remained “low probability of war”.

Disturbed by Zeira’s casualness was his opposite number in the Mossad, Zvi Zamir, himself a former general. Even in intimate meetings, Zamir noted, the intelligence chief never said what his assessments were based on. “It would never occur to me,” Zamir would write, “in meetings with the prime minister or defense minister, not to tell them on what sources my assessments were based and my evaluation of the credibility of those sources.”

By late September, it was not just foreign sources that were warning of war. Frontline troops could see it coming. A few days before Yom Kippur, a paratroop platoon relieving a unit on the Golan front was briefed by the departing intelligence officer who pointed out the Syrian positions opposite. “The whole Syrian army is out there,” he said before moving off. “I’m glad I won’t be here when the war starts.”

Along the Suez Canal, troops manning the Bar-Lev Line were being kept awake at night by noise across the waterway. The sounds were coming from behind ramparts the Egyptians had built on their side of the canal. Tanks and other vehicles could be heard arriving from the rear, evidently in great numbers. Dawn patrols along the canal banks began to note footprints of infiltrators who had crossed the canal during the night between Israeli positions and headed inland, behind Israeli lines. The Israeli general commanding forces in the canal area was informed by intelligence that the activities he was witnessing across the canal were not preparations for war but part of a routine military exercise to begin Oct. 1, six days before Yom Kippur. The general nevertheless told aides that war was coming and expressed grave concern that the reserves had not yet been mobilized.

Reserves constituted two-thirds of Israel’s army. In 1967, they had been mobilized more than two weeks before the Six-Day War broke out, time enough to turn a mass of civilians into soldiers again. But this time Zeira’s “low probability” mantra, spoken with the authority of Someone Who Knows, prevailed; there was no mobilization.

The day before Rosh Hashana, Dayan helicoptered up to the Golan Heights to issue a warning via military correspondents about dire consequences for Syria if it attacked. (The statement, aimed at deterrence, was duly picked up by the Syrian press.) At his insistence, Elazar and Zeira joined him on the visit, although both felt that Dayan was overreacting to Hofi’s warning two days before. From atop one of the volcanic cones that dotted both sides of the cease-fire line, a 24-year-old tank officer, Maj. Shmuel Askarov, briefed them. Pointing at the massive Syrian deployment before them, he said, “War is certain.”

Dayan asked Zeira to respond. “There will not be another war for 10 years,” said the intelligence chief.

In the traumatic aftermath of the Yom Kippur War, the question asked repeatedly by the public and press was how Israel’s leadership could have risked catastrophe by ignoring abundant evidence that war was at the gates. It would be 40 years before Israeli censors would permit revelation of one of the war’s best-kept secrets, one that offered at least a partial answer.

Early in 1973, helicopter-borne Israeli commandos had flown at night into Egypt with technicians to attach listening devices to communication hubs that were considered integral to any Egyptian war preparations. Dubbed “special means,” the system was regarded as an insurance policy against a surprise attack. Except for periodic testing, the system was kept dormant since its activation too often might be detected by the Egyptians. It was to be activated when warranted.

Few people knew of its existence but key decision makers—the defense minister, the chief of staff, the prime minister, and senior aides–did know. All assumed that Zeira, who was in charge of the system, had activated it as soon as the Egyptian military exercise began on Oct. 1 when Israel suddenly found Arab armies massed on two of its borders.

Elazar reportedly asked Zeira twice during the week before Yom Kippur if the system had indeed been activated and was given to understand that it had been and that it was not showing signs of war. But in fact it hadn’t been activated. Zeira had rejected pleas by his senior staff to do so on the grounds that the Egyptians might detect it. “What do special means exist for if not for situations like we’re facing,” asked the exasperated chief of signals intelligence. Zeira replied: “The situations you see are not the ones I see.” Confronting a major existential threat, the bulk of Israel’s strength remained unmobilized and the country’s leaders remained unaware of mortal danger.

The arrival of Ben-Gal’s brigade had increased the number of Israeli tanks on the Golan to 177. However, the three Syrian divisions on the other side of the cease-fire line numbered 900 tanks. To the rear, a few hours away, were two more divisions with 470 tanks. Opposite 11 Israeli artillery batteries were 115 Syrian batteries. On the Egyptian front the odds were similar. The Syrians calculated that Israeli reserve units could not reach the Golan in less than 24 hours. Damascus expected to capture the heights before then. Until Israel’s reserves joined the battle, the main burden of holding the enemy at bay would fall upon young conscripts—draftees—and their regular army commanders.

Informed by Hofi at 10 a.m. on Yom Kippur of the war warning, Col. Ben-Gal summoned his battalion and company commanders by radio to a meeting at the main army base in the northern Golan, Nafakh. All rose when he entered and he waved them back to their seats. “Gentlemen, war will break out today. A coordinated attack by Egypt and Syria.” He told the officers to return to their units and prepare the tanks for action. Their men, almost all of whom were fasting, were to be ordered to break the fast. The officers would meet again at 2 p.m. by which time the situation might be clearer. With that, the brigade commander drove to the front where he heard the birds break the stillness.

Ben-Gal, known to all as Yanosh, was a tall, commanding presence with a craggy face and large shock of unkempt hair. Born in Lodz, Poland, in 1938, he lost his family in the Holocaust and arrived in Palestine in 1944 with a group of orphaned children via the Soviet Union and Iran. In the absence of a family of his own, he adopted the army. To his officers and men, he radiated professionalism. He had a cutting tongue but some saw his brusqueness as a mask. Since assuming command of the prestigious Seventh Brigade the previous year, he insisted that training exercises emulate war conditions as closely as possible. He drilled his men intensely in gunnery and held weeklong exercises in which the brigade operated only at night. Frequently, in the middle of an exercise, he would announce a change in mission, requiring rapid decisions by commanders and movement through unfamiliar terrain.

The officers were just arriving for the 2 p.m. meeting when MiGs dropped bombs on the camp. “Everyone to your tanks,” Ben-Gal shouted. A sentry already lay dead at the gateway.

With Ben-Gal’s tanks still in rear holding areas, the 40-mile-long front was held by the 188th Armored Brigade commanded by Col. Yitzhak Ben-Shoham. A platoon commander, Lt. Oded Beckman, was trying to persuade a reluctant tank crewman to break his fast when an artillery barrage hit with a deafening roar. Beckman could see the ground ripple as the Syrian guns methodically worked their way across preplanned target areas. His tanks managed to scramble out of the way just in time. Smoke blanketed every crossroad, military camp, strongpoint, command center, tank park and communications facility on the heights.

Ben-Gal drove along the front in his halftrack to see if the Syrians were sending in their tanks. Dust and smoke reduced visibility to virtually zero. Near the abandoned town of Kuneitra, he ordered his driver to stop. From across the line he detected a distant clanking and the sound of engines. Abruptly the shelling ceased and from the settling dust emerged a mass of Syrian tanks.

As Lt. Beckman’s company moved up to the line, he was unable to control the shaking of his limbs, even though his mind functioned clearly. He saw a Syrian tank column led by a bridging tank approach the anti-tank ditch that had been dug in front of the Israeli line. He let a bridge be laid across the ditch, then hit the first tank to mount it when it was half way across. When a second tank mounted the bridge to push the first across, Beckman hit it too, effectively blocking passage. A second bridging tank approached and he hit it before it reached the ditch.

Maj. Askarov, the young deputy battalion commander who had briefed Dayan and Zeira 10 days before, raced to the front from a rear camp together with half a dozen of his tanks. He mounted a tank ramp but at first could see nothing because of the smoke. The upward sloping ramps permitted tanks to fire from an elevated position with only their guns and turrets exposed to the enemy. As the Syrians lifted their barrage, a swarm of tanks came into view led by five bridging tanks. He managed to hit the three within range.

Askarov then noticed that none of the tanks he brought had come up the firing ramp. He called on their commanders by radio but got no clear response. Askarov told his driver to reverse down the slope. They halted alongside the nearest tank and Askarov climbed aboard. Drawing his pistol, he pointed it at the commander’s head. “Get up there or I shoot.” Within a minute, all the tanks were on the ramps, firing.

Given the number of Syrian tanks and personnel carriers passing under the Israeli guns it was like shooting fish in a barrel. Except that some of the fish shot back. One after another, the Israeli tanks were hit and most of their commanders killed. Askarov’s tank was hit four times but remained operational. The Syrians pressed forward, seemingly indifferent to their losses. He moved from ramp to ramp to create the impression of a large force. He had no illusions about surviving the day intact.

Within two hours the crew recorded 35 tank kills. Finally, their tank was hit and Askarov was propelled out of the turret onto the ground. Retrieved by troops from a nearby bunker, he was taken to hospital later in the day. It was there that he would recall Zeira’s prediction.

The 10 infantry outposts spaced along the cease-fire line were each backed by a tank platoon behind ramps a few hundred yards away. Lt. Shmuel Yakhin’s three tanks supported an outpost overlooking the main road from Damascus which had begun to stream with tanks and trucks. Yakhin’s tanks opened fire at 2,000 yards, working their way methodically down the line of vehicles. After the first ranging shots, the second shot almost always hit. At one point, Yakhin pulled back in order to load shells from the belly of the tank into the gun turret. The loader was outside the tank when Yakhin, in the turret, looked up to see a Syrian tank 400 yards away pointing its gun at him. The loader managed to scramble back into the tank and get a shell into the gun breech. The gunner fired, holing the Syrian tank before it got off its shot. The reaction time of Israeli crews would prove a major factor in offsetting the disparity of forces, the Israelis getting off two or more rounds in the time it took the Syrian crews to fire one.

Returning to the Golan late Saturday afternoon from Tel Aviv where he had been consulting with the chief of staff, Hofi assigned defense of the northern Golan to Ben-Gal, leaving the southern half to the hard-pressed 188th Brigade.

Hofi brought with him as air force liaison Gen. (res.) Motti Hod who, as air force commander in 1967, had overseen the destruction of the Egyptian air force in three hours. At the command bunker in Nafakh, Hod listened to the radio network crackling with reports from the front as Hofi and his staff issued orders and debated the enemy’s likely moves. Hod had directed numerous air actions from bunkers but never from one where shells were exploding outside. What disturbed him more than the artillery or the dire reports from the front was what he saw happening in the bunker itself. Everybody was reacting—to events, to each other—but it was plain to him that nobody, from the tank commanders in the field to Hofi and his staff, had time to think. How can you conduct a war without thinking, Hod asked himself.

It was not until midnight that Hofi grasped the scale of the Syrian penetration. Three hundred tanks had broken through in the southern Golan where there were fewer than 30 Israeli tanks left—almost out of ammunition and fuel after 10 hours of combat. “Only the air force can stop them,” Hofi told Elazar. However, it would soon become apparent that the air force, stymied by the SAMs, couldn’t. The Israeli tanks would have to stop a Syrian force that outnumbered them by almost 5 to 1.

Refreshed by a few hours’ sleep in his tank on the Hermonit ridge, Avigdor Kahalani rose in the turret at first light Sunday to breathe deeply of the chill morning air. A rumbling emanating from the landscape sounded like the distant roar of lions preparing to feed. It was the sound of tank engines revving up. Dark smoke rose from vehicles on both sides of the line. In the distance, clouds of dust were already being thrown up by Syrian tank columns on the move. Raising his company commanders on the radio, Kahalani wished them good morning and told them to prepare for a Syrian attack.

One hundred yards to his front were two long tank ramps which he had not seen at night. He ordered his tanks to take up positions there.

The tanks descended in a broad line, the commanders standing in the turrets. Before them was a brown, barren vale. This was the Kuneitra Gap through which the Syrian tanks would move if they were heading for Nafakh and the Jordan River. At first Kahalani could detect no movement. Then he noticed a single tank throwing up black smoke. In a moment, other tanks could be seen detaching themselves from the landscape and moving forward. The Syrians were commencing their attack.

“Our sector,” he called to his tank commanders in a litany straight from a training exercise. “Range 500 to 1,500 meters. A large number of enemy tanks moving in our direction. Take your positions and open fire. Out.”

The tank guns began barking almost immediately. Kahalani’s own tank joined in, his operations officer, Gidi Peled, directing the fire. Unlike other tanks, which had four-man crews, command tanks shoehorned in an operations officer as well.

“Kahalani, this is Yanosh.” The voice of the brigade commander, who was monitoring the radio net, was crisp. “Report.”

The slope below Kahalani was swarming with tanks. The Syrian tank commanders had their hatches closed. Periodically, they halted and fired two shells at the Israeli turrets on the skyline before starting forward again.

Tanks were burning all over the slopes. “This is the battalion commander,” said Kahalani. You’re doing great work. This valley is beginning to look like Lag B’Omer,” a reference to the bonfires lit on that holiday. “We’ve got to stop them.”

The Israelis were taking hits too. Kahalani could see burning Centurions and the radio brought first reports of casualties. One of his company commanders was dead. From time to time, tanks backed off to permit crewmen to load ammunition into the turret. Kahalani watched the tanks move unhesitatingly back up to the firing line.

Ben-Gal moved around the battlefield, fine-tuning the defense as he moved companies and even platoons from one sector to another in anticipation of shifting Syrian pressure. It was his principal task, as Ben-Gal saw it, not to react to specific Syrian moves (his commanders on the ground would attend to that) but to imagine what the problems were likely to be in another 15 minutes or two hours. To effectively command, it was important to be near the heart of the action. Only thus could he understand the flow of the battle and detect weak spots on both sides.

Kahalani was struck by the courage of the Syrians who passed around their burnt-out tanks and pressed on. But it appeared to him a mindless courage. If he were attacking, he thought, he would slow the pace and attempt to find another opening. The Syrians continued banging their head against the same wall. However, with a wall as thin as the Israeli line and a force as large as the Syrians’ there was no telling how the story would end.

As his crew pulled back to load shells, Kahalani glanced along the line. The tanks were no longer the neat fighting machines they had been in the morning. Sleeping bags and other personal accoutrements lashed to the exterior of the tanks were riddled with shrapnel. One tank was burning. The gun of another hung askew. All the faces in the turrets were dark with powder and dust. He could sense, however, an easing of the pressure. Here and there, enemy tanks continued to fire but when he mounted the rampart he could see that the great armored wave had broken.

“Kahalani. This is Yanosh. What’s happening?”

“We’ve managed to stop them. The valley below me is full of burning and abandoned tanks.”

Ben-Gal asked if he could estimate their numbers. “Eighty or 90,” said Kahalani.

“Well done. Well done.” Coming from a hard case like Ben-Gal, the warm words were not a compliment Kahalani took lightly.

MiGs appeared overhead and dropped bombs that hit 100 yards behind the rampart. “Where’s our air force?” Kahalani mused. Neither he nor Ben-Gal had any idea of the desperate situation in the southern Golan or Sinai.

By noon the Syrian artillery had abated. For the first time in 24 hours, men got out of the tanks, one at a time, to relieve themselves. Kahalani drove to Ben-Gal’s command post.

“I’ve lost a lot of men,” he reported. He sensed that the brigade commander did not want to talk about it.

“I want you to know,” said Ben-Gal, “that the Syrians are not stopping. They’ve got enough tanks and they’ll try to break through again.”

As Kahalani started back to his tank, the brigade operations officer, who had followed the progress of the battle on the radio net, embraced him. “You were great, brother.”

Israel’s leaders realized by now, with a pang of guilt and fear, that they had prepared for the wrong war and that basic assumptions on which their confidence had rested were illusions. The day before the war, when reconnaissance photos showed an astonishing build-up of tanks and artillery behind Egyptian lines, Dayan was taken aback. He told his generals, “You people don’t take the Arabs seriously enough.” That was precisely the problem. The Arab soldiers were not running—they were attacking and they were fighting well, with new Soviet weapons, some of which Israel had no answer for, and new spirit. The IAF, which was supposed to be the key to breaking up a surprise attack, was losing planes to the SAMs at an alarming rate. Surprised by the new Soviet anti-tank weapon, the Saager, Israel lost scores of tanks in Sinai before tank crews in the field came up with an effective response. Israeli intelligence, presumed to be all-knowing, had been responsible for an incredible glitch that threatened to bring disaster on the country. Everything was coming apart and the war was hardly a day old. If the Arabs had succeeded in accomplishing so much in this span of time, what else lay in store? It was known that Iraq and other Arab countries were planning to join the fight.

Soldiers on the ground were generally too focused on stopping the enemy and staying alive to spare thoughts about national survival. Sometimes, however, they too were gripped by dark thoughts, particularly airmen who had a broader view. A Phantom pilot who returned from a mission over the Golan was asked by a female operations clerk at his base what it was like. He described to her columns of Syrian tanks rolling slowly across the Golan Heights like hordes of giant ants, with nothing to stop them. Alarmed, the clerk said that her brother, a tank crewman, “is up there.” The pilot absently said “was up there,” as if nothing could survive the Syrian juggernaut. (He later apologized to her.) The acting commander of a Phantom squadron, Ron Huldai (present mayor of Tel Aviv), briefing his pilots after their first day’s encounter with the SAMs, said, “Take a good look at each other. When this war is over, a lot of us won’t be here.”

Almost half of Israel’s total casualties in the Yom Kippur War—2,600 killed and 7,300 wounded—were inflicted on the Golan. Many of the tanks that were disabled, probably most, were repaired in the field by maintenance crews, usually within a day. There were, of course, total losses as well but these were made up for by Syrian (Russian) tanks captured intact after being abandoned.

A normally ebullient paratroop battalion commander in the southern Golan, Lt. Col. Yoram Yair, was beset with morbid thoughts as he watched a succession of Israeli planes being downed by SAMs. Scores of his men were trapped in forward outposts and he was unaware of any planned counterattack that might reach them. When a Syrian tank force rolled into Kibbutz Ramat Magshimim (which had been evacuated shortly before), a mile north of Yair’s command post, he was ordered to pull back. He sent his staff back but remained to monitor the Syrians’ movements. Years later he would recall what went through his mind at the time. “I was thinking that the episode of the Jews here (in Israel) in the 20th century had reached its end.”

For civilians too, the abrupt switch from tranquility on Yom Kippur eve to war half a day later—without what psychologists would call “the positive process of anticipatory fear”—was a shock that would be a long time healing.

Fire,” Kahalani shouted. “What range?” asked Kilion. They were so close he did not realize that the dark object filling his scope was a Syrian tank. “Just fire.

The surprise attack paralyzed many. “You break into a cold sweat and your mind freezes up,” a deputy division commander, a hero of the Six-Day War, would later say. “You have difficulty getting into gear and you react by executing plans you’ve already prepared, even though they’re no long relevant.” Senior officers tried to simultaneously grasp what was happening, how it could have happened, and what had to be done to reverse what happened. A brigade commander noted that officers at his level, even when they seemed unaffected, generally needed two days before the ground steadied beneath their feet.

The most notable victim of shock was Israel’s leading military icon, Moshe Dayan. Flying up to Northern Command shortly after dawn Sunday, Day Two of the war, he was told bluntly by Hofi that the Golan might have to be abandoned. Gen. Dan Laner, commander of a reserve division, shared Hofi’s pessimism. “The fighting is over in the southern Golan. We don’t have anything to stop them with.” The Jordan River bridges were being prepared for demolition in the event the Syrians approached and documents and ammunition were being trucked down from the heights.

Dayan’s physical appearance was dismaying. The 58-year-old minister was pale and his hands shook. The relentlessly grim picture confronting him since the war began—and the enormity of Israel’s miscalculation regarding the Arabs—had touched an apocalyptic chord which would resonate for days. In conversations, he began using the phrase “the Third Temple is in danger,”—a reference to the state of Israel. Nevertheless, his insights and ability to make sound tactical and strategic assessments remained unimpaired, with one notable exception. Patched through to the air force commander, Gen. Benny Peled, he asked him to call off an elaborate attack on Egypt’s SAM batteries by virtually the entire air force, which was just getting underway. Instead, he said, dispatch aircraft against Syria. “This is not a request, this is an order.”

It touched off furious reactions among Peled’s commanders. Tagar, as the operation was called, was the one chance, as they saw it, to eliminate SAMs from Egypt’s skies. If successful, they would execute a similar attack over Syria. Both operations, however, were now called off. Had they been successful, and the air force was able to operate freely against the Arab ground forces and sever the bridges across the Suez Canal, it would have been a totally different war.

After returning from the north, Dayan met with Meir and her inner cabinet to offer his stark assessments. For long the embodiment of national self-confidence, he was now probably the most depressed man in the country, certainly the most depressing.

The army’s lines on both fronts had broken, he told the ministers. Israel must cut its losses and pull back—in Sinai to the passes; on the Golan, to the edge of the plateau. There the troops would hold out “until the last bullet.”

The impact of Dayan’s words on Meir was predictable. She heard them “in horror,” she would write, and the thought of suicide crossed her mind. Her long-time assistant, Ms. Lou Kedar, was at her desk in the next room when Meir rang. “Meet me in the corridor,” she said. Although Meir had the country’s top military and political advisers on call, she chose to share her deepest feelings, and fears, with her old friend. Kedar was shocked at her pallor and the look of despair. Leaning heavily against a wall, the prime minister related in a low and terrible voice her conversation with Dayan. He had offered his resignation but she had rejected it.

For a moment, Meir stared hollowly at Kedar, her mind elsewhere. Slowly, her expression began to change and color seeped back into her cheeks. “Get Simha,” she said. Through Ambassador Simha Dinitz in Washington, Meir intended to start pressuring the American administration for arms. Excruciating days still lay ahead, but psychologically the prime minister had touched bottom. When Dayan on Day Two suggested staging a nuclear demonstration over the desert in Egypt and Syria as a warning, she said “forget it.”

The High Command had been overtaken by a flabbiness of thought that brought the country to this sorry point. It had permitted itself to believe that it could rely on the air force, rather than mobilization of troops, to thwart a possible surprise attack even though it was already clear that the air force would have difficulty coping with the SAMs. It had known about the Sagger anti-tank missile from the Americans who had encountered them in Vietnam but the armored corps had not yet informed tank units of their existence and was taking its time developing a tactical solution. (Tank crews on the Sinai front would work out solutions on their own but only after a tank division had been mauled.) It insisted on manning the Bar-Lev Line against the advice of Gen. Ariel Sharon and others who warned that the thin line was patently indefensible and would trap not only its defenders but also tanks that went to their aid. As one officer after the war would explain the prevailing mindset: “The thinking was that we’re facing Arabs, not Germans.” Now the outcome of the war rested on the caliber and determination of the troops and of the field commanders who led them.

In the northern Golan, the Seventh Brigade was engaged in its own war, largely detached from what was happening elsewhere on the Golan. It was a classic defensive battle, the kind that IDF doctrine ignored in favor of offense. The brigade had filled the Kuneitra Gap with masses of destroyed Syrian armor. In doing so, it lost more than half of its own tanks but the critical juncture still lay ahead.

The Syrian High Command, in a final effort to break through, had assembled on Day Four 160 tanks in this sector, four times Ben-Gal’s remaining strength.

His men were exhausted and emotionally numb. A brigade staff officer fell asleep as Ben-Gal was talking to him. The contending armies had reached the endgame. One final effort, five more minutes of endurance, could make the difference.

The day began with the most massive Syrian barrage yet. It was so fierce that Ben-Gal for the first time ordered the tanks on the ramparts, the focus of the Syrian shelling, to pull back a few hundred yards.

The brigade commander had taken up position near Kibbutz El-Rom on high ground two miles behind the tank ramps, monitoring his three battalions. He could see heavy artillery fire on the ramps. On the radio, tank commanders were reporting ammunition running out. There could be no more than a dozen or so tanks left intact there.

Four Syrian helicopters passed directly overhead. Four others followed. One was shot down by ground fire but the others landed near Nafakh, disgorging commandos. Ben-Gal could not spare tanks to deal with them because his front was at this very moment cracking.

Lead elements of the Syrian tank force were approaching the empty ramps and Ben-Gal could not make contact with the tanks that had pulled back. He ordered battalion commander Menahem Rattes on the northern flank to move south to fill the gap. As Rattes’ small force approached the area, he and his deputy were killed and his tanks scattered.

After days of hands-on direction, Ben-Gal’s control was unraveling as officers were hit and orders not passed on. There appeared to be no alternative but to have the tanks fall back. Even if they managed to outrace the Syrians to a new line, however, they would not be able to hold it for more than half an hour, he estimated, in the absence of proper defensive positions. He decided on a last desperate bid to shore up the collapsing line.

“Kahalani, this is Yanosh. Move out. Fast. Over.”

The battalion commander had been waiting impatiently for the order. As he moved from the right flank back toward the center, he ordered his men to be prepared to fire without warning. The ramp, he saw, was empty except for disabled tanks, Israeli and Syrian. The Israeli tanks remaining were scattered 500 yards to the rear.

Ignoring them for the moment, Kahalani cut across a plowed field toward a wadi to the left. It was through the wadi, with its navigable incline, that Syrian tanks had previously penetrated onto the Israeli high ground. Kahalani wanted to make sure it was empty before reoccupying the ramp. A pile of dark basalt stones, cleared by kibbutz farmers, stretched across much of the field. As Kahalani’s tank turned its corner, he came on three Syrian tanks. Two were static, the third was moving beyond them.

Kahalani swung the gun at the nearest tank, just 20 yards away. Tank commanders could override the gunner’s controls in order to roughly aim the gun but it was for the gunner to make the final adjustments.

“Fire,” Kahalani shouted.

“What range?” asked Kilion. They were so close he did not realize that the dark object filling his scope was a Syrian tank.

“Just fire.”

Kilion hit it and then the other two.

A fourth tank raced toward them but one of the tanks with Kahalani stopped it. Kahalani positioned himself at the head of the wadi. After Kilion cleared it by hitting five more tanks as they climbed, Kahalini could see a mass of Syrian tanks approaching in the valley beyond.

The tanks behind the firing ramps were scattered like lost sheep. If they were to survive, it was essential to get them up the ramp before the Syrians reached it. Only from there might the vast disparity in numbers be offset. When his calls drew little response, Kahalani understood that most of the tank commanders preferred not to hear him. They had been under constant artillery bombardment for four days and the Syrian air force had had several goes at them. Half their comrades were dead or wounded and they had hardly slept since the battle started.

The tank commanders could no longer bring themselves to face the curtain of fire on the ramp. They had reached their breaking point.

In the tank with Kahalani, Lt. Peled had since the start of the war felt fear knotted in his stomach. He had seen fear in Kahalani’s face as well. But until now the battalion had operated like a well-tuned racing car with fear along only as an unobtrusive passenger. Now, as he monitored the non-response to Kahalani’s calls and noted that tank commanders were keeping their hatches closed, it seemed to Peled that the passenger had moved into the driver’s seat. He had reconciled himself to the certainty that he would not survive this day intact.

A Syrian tank topped the ramp like some prehistoric beast, rising high to crest the front edge and then dropping down onto the firing position. As its snout swiveled in search of prey, Kahalani, adjacent to the wadi, swiveled his gun and Kilion set the tank aflame. When another tank from the Syrian spearhead came over the top, it was knocked out by one of the tanks to the rear of the ramp.

The sound of explosions was constant. Syrian and Israeli crews escaping from damaged tanks scrambled over the terrain, ignoring each other as they tried to make their way back to their respective lines. A nightmarish dilemma gripped Kahalani. Only he could see the approaching danger in the valley and only he could muster the tank crews to regain the ramp. Nothing but the personal example of the senior commander on the spot would get the paralyzed tank commanders, most of them 19- and 20-year-olds, to move. But he could neither abandon the wadi, through which Syrian tanks could debouch at any moment, nor make radio contact with most of the tanks behind the rampart. Ten Syrian tanks had already topped the ramparts and been hit. In a little while, 20 or 30 would come over and there would be no stopping them. Kahalani weighed the possibility of ordering the men to fall back to a second line but he feared they would be hit before they made it.

The same thought was occurring to Ben-Gal. He prepared to issue a pullback order but then called instead to Gen. Eitan to report his intentions. The division commander was watching the battle from an adjacent hilltop. He could see the small Israeli tank force sheltering behind the crest of the ridge and the mass of Syrian tanks surging across the valley toward it. Behind the Syrian tanks a line of infantry personnel carriers and supply vehicles stretched two miles.

“Hang on five minutes more,” said Eitan. “Reinforcements will be moving up to you.” They both knew that the minutes Eitan asked for were not measured by the clock but by calculations of life and death, personal and communal. The division commander told Ben-Gal that a new unit had been put together at the rear of the heights and was setting out.

On the radio net, Kahalani heard a new voice addressing him, a tank commander from Rattes’ unit introducing himself as “Sergeant, Platoon Four.” It was a cool voice and Kahalani ordered the sergeant to come alongside. A solution to his dilemma seemed at hand. “Sergeant, Platoon Four, take my position and guard the wadi opening. Destroy any Syrian tank that tries to come up.”

“This is Sergeant, Platoon Four. Alright. But I don’t have any shells left.”

On the radio net Kahalani heard Maj. Meir Zamir, flanking his position to the south, reporting a massive Syrian attack. Zamir asked permission to shift the few tanks remaining to a better position slightly south. “Negative,” said Ben-Gal, aware of the gap this would open. “Stay where you are. Kahalani, report.”

“This is Kahalani. Not all the tanks here have made contact with me. I’m not managing to control them and they’re constantly drifting to the rear.” In his reports to Ben-Gal since the war started, he had tried to avoid sounding alarmist in order not to add to the brigade commander’s burden. Even this report was phrased moderately but the facts were stark. Ben-Gal said he would try to get more tanks up to him.

“Sergeant, Platoon Four.” said Kahalani into his mouthpiece. He had made a decision. “I know your situation. Stay here in my place and don’t let anyone up from the wadi. Clear?”

“This is Sergeant, Platoon Four. I remind you that …”

“I know. Stand high in the position so that they see you. If they see you well they won’t enter.”

Starting toward the drifting tanks, Kahalani addressed their commanders. “This is the battalion commander. Whoever hears me, raise your flag.”

There were 10 tanks that he could see. Most of their commanders raised flags. “We must regain the ramp. Otherwise …” His remarks were interrupted by two planes diving on them and dropping bombs. None of the tanks was hit. As the second plane pulled up Kahalani saw a Star of David on its tail. Despair threatened to overwhelm him.

“This is the battalion commander,” he began again. “A large enemy force is on the other side of the ramp. We are going to move forward to regain the ramp. Move.”

His tank started forward and a few followed, but with agonizing slowness. Two Syrian tanks come over the top. Kilion fired along with other tanks, setting the Syrians aflame. But the tanks that had moved forward now pulled back to the more sheltered position from which they had started. Seeing how his own tank was exposed to any Syrian tank topping the ramp, Kahalani understood better the reluctance of the tank commanders to cross the open space.

Ben-Gal came on the radio to inform him that he was sending him a number of tanks under the command of Lt. Col. Eli Geva, from the 188th. Another ad hoc unit was already on its way to relieve Zamir’s company further south. Turning, Kahalani could see the dust clouds of approaching tanks in the distance. For the first time since the battle began, points of light were beginning to appear.

“This is the battalion commander.” Kahalani realized that straightforward commands would no longer work. “Look at the courage of the enemy coming over the ramp. I don’t know what’s happening to us. They are only the Arab enemy we have always known. We are stronger than them. Start moving forward and form a line with me. I am waving my flag. Move.” He had spoken in an even tone but shouted the last word.

A platoon commander had been sitting in his buttoned up tank literally shivering from fear. The rest of his crew was in the same condition, their nerves shattered. He had not fled to the rear, the lieutenant told himself repeatedly. But he was unable to force himself to move forward or to stop shaking. To his front he could identify the battalion commander’s tank by its markings and the flag being waved. He had heard Kahalani’s calls on the radio but had not responded. This time the battalion commander’s words stung. Was he suggesting they were cowards? “Move,” the lieutenant said to his driver. They joined the other tanks that had started forward.

“Don’t stop,” Kahalani called, as he watched the tanks form into line. “Keep moving. Keep moving.”

A Syrian tank came over the ramp and Kahalani swiveled his turret but the tank next to him fired first. Kahalani was exhilarated as he glanced at the formation.

“You’re moving fine,” he called. “Don’t stop. Be prepared to fire.”

The hatches were open now but the tank commanders kept low in their turrets, their eyes just above the edges. As they climbed they had to make their way between disabled Syrian and Israeli tanks, some of them burning. Not until they pushed up the final yards into the firing positions could the tank commanders see the valley.

The Kuneitra Gap was dark with vehicles. Most were static—tanks, personnel carriers and trucks knocked out during the previous days of fighting and this day’s battle. But among them tanks were moving doggedly forward. The furthest were 1,000 yards distant, the closest only 50 yards.

The Centurions commenced fire, each tank commander unleashing his pent-up fury and fear on the approaching enemy.

“Aim only at moving tanks,” called Kahalani. He was afraid they would waste ammunition on disabled tanks. Syrian crews could be seen jumping from damaged tanks and running to the rear. Eli Geva’s Centurions now reached the ramp and joined in the shoot. For the first time, the Syrian tanks seemed to waver and search for a more protected approach but they kept coming. Finally, there were no more targets.

A heavy barrage descended on the ramps and the tank commanders pulled back into the turrets. When the shelling subsided, Kahalani put his head back out. Nothing was moving in the valley except flames licking at stricken tanks. When he reported to Ben-Gal, the brigade commander asked how many Syrian tanks had been hit. “We’ve destroyed 60 to 70 tanks,” said Kahalani.

The Syrian attack on Ben-Gal’s right flank was likewise moving toward its climax. Maj. Zamir was down to two tanks and again requested permission to withdraw. Ben-Gal ordered him to stay. Help was on the way, he said. Just hang on a few minutes more. The relief force consisting of 11 tanks was led by Lt. Col. Yossi Ben-Hanan who had been on his honeymoon in Nepal when he heard on the BBC of the outbreak of war and caught the first plane back. He had landed in Israel with his wife that morning and headed straight for Northern Command. The tanks and crews had earlier been assembled in the rear by Shmuel Askarov who had “escaped” from the hospital and returned to the Golan despite his wounds.

Maj. Zamir, his ammunition exhausted, could wait no longer. The relief force arrived at precisely the moment that he was pulling back. Ben-Hanan and Zamir exchanged a nonchalant “shalom” as they passed each other. Topping a small rise, Ben-Hanan saw a T-55 heading toward him just 50 yards away.

“Stop,” he called. “Fire.” His war had begun.

Askarov took up position alongside Ben-Hanan as the rest of the improvised unit formed a battle line. Shell splinters cut Ben-Hanan’s face and broke his eyeglasses. He passed command to Askarov and pulled back briefly to be treated by a medic. Askarov set ablaze a tank just 40 yards from him but was struck in the head by a bullet and seriously wounded. Once again, he was carried to the rear.

As Eitan watched the battle, his intelligence officer, Lt. Col. Dennie Agmon, suddenly said, “The Syrian general staff has decided to retreat.” Eitan looked at him askance. Agmon had not been listening to the radio net and had no visible source for that far-reaching pronouncement. “Look there,” Agmon said, pointing with his binoculars. Support vehicles at the tail of the Syrian column were turning around. This was not a panicky retreat from the battlefield but an orderly pullback, beginning with vehicles at the rear, plainly a command decision.

Ben-Gal came forward to watch from a ridgetop as the Syrian wave ebbed. In the valley, lay 260 Syrian tanks as well as numerous armored personnel carriers, trucks, and other vehicles which his brigade had stopped during the past four days. Many of the tanks had been abandoned intact.

In the afternoon, the tanks pulled back a few at a time for ammunition and fuel. Kahalani drove to the brigade command post to talk with Ben-Gal who had not slept for four days except for brief catnaps. In an upbeat tone that sounded forced, the brigade commander said, “We’ve been ordered to counterattack into Syria.” Gen. Eitan wanted Ben-Gal to attack the next day in order not to give the Syrians respite and to cross the cease-fire line. But Ben-Gal asked for a day to permit the exhausted men to rest and to fill the enormous gaps in his ranks. “Phase One is over for us,” he told Kahalani. “Phase Two is about to start.”

Gen. Elazar, who was overseeing the Egyptian front as well, came north at dawn the following day on a helicopter flight from Tel Aviv that offered him a blessed hour of sleep. After reviewing the attack plan, the chief of staff continued on with Hofi to meet divisional and brigade commanders at the Nafakh camp. It was his first meeting with them since the war began. The sight of the unshaven, bone-weary faces touched him, particularly Ben-Gal’s haunted visage. The coming battle, he told them, would be a turning point. It was doubtful that they could reach Damascus but their objective would be to get close enough to threaten it with artillery.

Ben-Gal summoned his battalion commanders for a briefing before the attack. Three-quarters of the brigade’s tank crewmen who had started the war five days before were wounded or dead. But replacements overnight had brought the brigade back up to full strength, 100 tanks and crews.

When the briefing was over, Ben-Gal took Kahalani aside. “Listen,” he said, placing a hand on Kahalani’s shoulder. “I met the chief of staff this morning and I want you to know that I told him what you did.” Ben-Gal seemed to have trouble expressing himself. “I told him you were a Hero of Israel (the name of Israel’s highest medal for valor). I wanted you to know this.” Backing away from his emotion, Ben-Gal shook Kahalani’s hand and said awkwardly, “It’ll be alright. See you.”

Lt. Peled watched the scene in astonishment. The operations officer had not heard the conversation but it was plain from Ben-Gal’s body language that the brigade commander was moved and was making personal contact. It was a view of Yanosh Ben-Gal he had never expected to see.

Back at his battalion’s staging area, Kahalani asked for the officers to be assembled. He scanned their faces as they sat on the ground in front of him. Most were new. “First, for all those who have just joined us and still don’t know where they are, this is the 77th Battalion of the 7th Brigade. Battalion commander Kahalani stands by chance before you.” A hesitant smile appeared on the tense faces. “Before I explain our mission, I want to know who you are and what your tasks are.”

Each new man was asked to tell which company he was assigned to, what he had done since the beginning of the war, and from what organic unit he came. A number were reservists. Kahalani asked each of the latter personal questions—what part of the country they were from, what they did in civilian life, whether they were married, how many children they had. Lt. Peled, accustomed to the Spartan tone of briefings in the standing army, found these personal questions puzzling. What had they to do with the business at hand? Only later would he understand that Kahalani was spinning a human web, creating of this disparate group of strangers thrown together on a remote battlefield a cohesive team willing, in moments of danger that would shortly be upon them, to risk death because he asked them to.

Only when this bonding was done did Kahalani turn to Peled and ask him to unroll the map he was carrying. “The brigade has been ordered to break through the Syrian lines,” said Kahalani. “Our battalion will spearhead the attack.” He pointed out their route and spelled out the order in which the units would move. “Good luck. And, the main thing, fight like lions. We’re moving out in 20 minutes. On your tanks.”

***

Joining the 7th Brigade in crossing the cease-fire line were the other reserve brigades which had mounted the Golan since the beginning of the war and helped drive the Syrians from the heights in bitter battles. The combined force advanced 12 miles eastward, almost half the distance to Damascus, when two Iraqi armored divisions and a Jordanian brigade joined the battle. The Israeli drive halted within artillery range of the outskirts of Damascus. Israel’s strategic focus shifted to the Egyptian front where the army had succeeded in crossing the Suez Canal behind Gen. Sharon’s division and begun advancing toward Cairo.

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat rapidly agreed to a cease-fire and exchange of prisoners. But Syrian President Hafez al-Assad refused to do so until Israel agreed to his territorial demands, which included return of all land captured in the war as well as half the Golan Heights captured in the Six-Day War. In order to get its POWs back without excessive delay, Israel agreed to pull back from the newly captured territory inside Syria, which it had never intended to hold, and return a mile-wide strip on its side of the 1967 cease-fire line. With Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s active intervention, the two sides signed a disengagement agreement in Geneva in June 1974.

Abraham Rabinovich is the author of, among other titles,The Yom Kippur War, The Boats of Cherbourg, and The Battle for Jerusalem.