Meet the Skirt-Wearing Rock Star Cousin of Moshe Dayan Who Could Be Prime Minister

Touring on a new album, Aviv Geffen talks about Rabin, Mizrahi music, and why the Dayans are no Kennedys

Aviv Geffen wasn’t Israel’s first rocker, but he may have been the first to adopt the rocker’s role in an unprecedented totality: The unrelenting struggle for an audience coupled with the refusal to please fans, to whom the wrong things must be said at the wrong time. Indeed, Geffen, one of Israel’s most iconic and enduring rock stars, was, for years, filled with rage. He used to chant, “We’re a fucked-up generation” and sing songs that dealt, not always kindly, with Geffen’s favorite subject matter of the last 20 years: his painful childhood, courtesy of a father who wasn’t available when the son needed him most. (The father is Yonatan Geffen, a songwriter who penned some of Israel’s greatest hits.) His musical influences include the local—notably Shalom Hanoch and Arik Einstein—and the foreign—David Bowie, Bob Dylan, and Supertramp. A dozen of his albums in Hebrew, for which he wrote most of the lyrics and music, reached gold and platinum.

But on “Pain on Top of Pain” (ke’ev al ke’ev), the second single off Geffen’s upcoming album, the singer strikes a different tone. The song begins, “I made a promise that I will not return here. … My childhood is buried in some song which I cannot recall,” and ends with very un-Geffen-like sentiment, “I forgive because there’s no time left.”

A country that extols family life might have needed the son of perhaps its most illustrious family to introduce the notion of unapologetic individualism. Geffen’s uncle was Moshe Dayan, the general-turned-politician; another relative was Ezer Weizman, the general-turned-president. To list all of Geffen’s famous relatives in arts and politics is nearly impossible. Geffen recalls how he, then a young boy, together with his Uncle Moshe (“an amazing uncle”), would piece together ancient shards onto an archaeological artifact in Dayan’s collection. Geffen purports to follow the example of his most famous uncle, but with a twist. “I’m the radical who wants to do the opposite of everything he did. He conquered Jerusalem, I want to give it away. He was macho, I want to be gentle.”

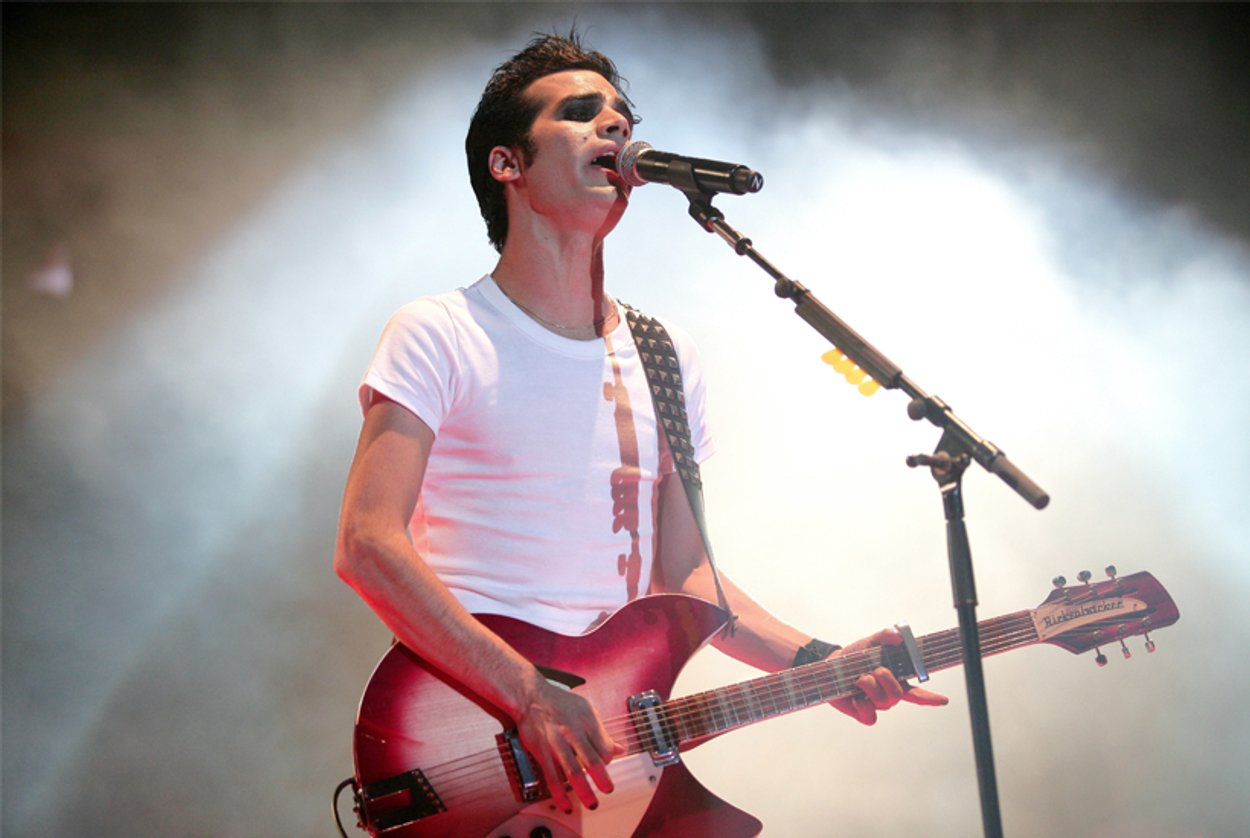

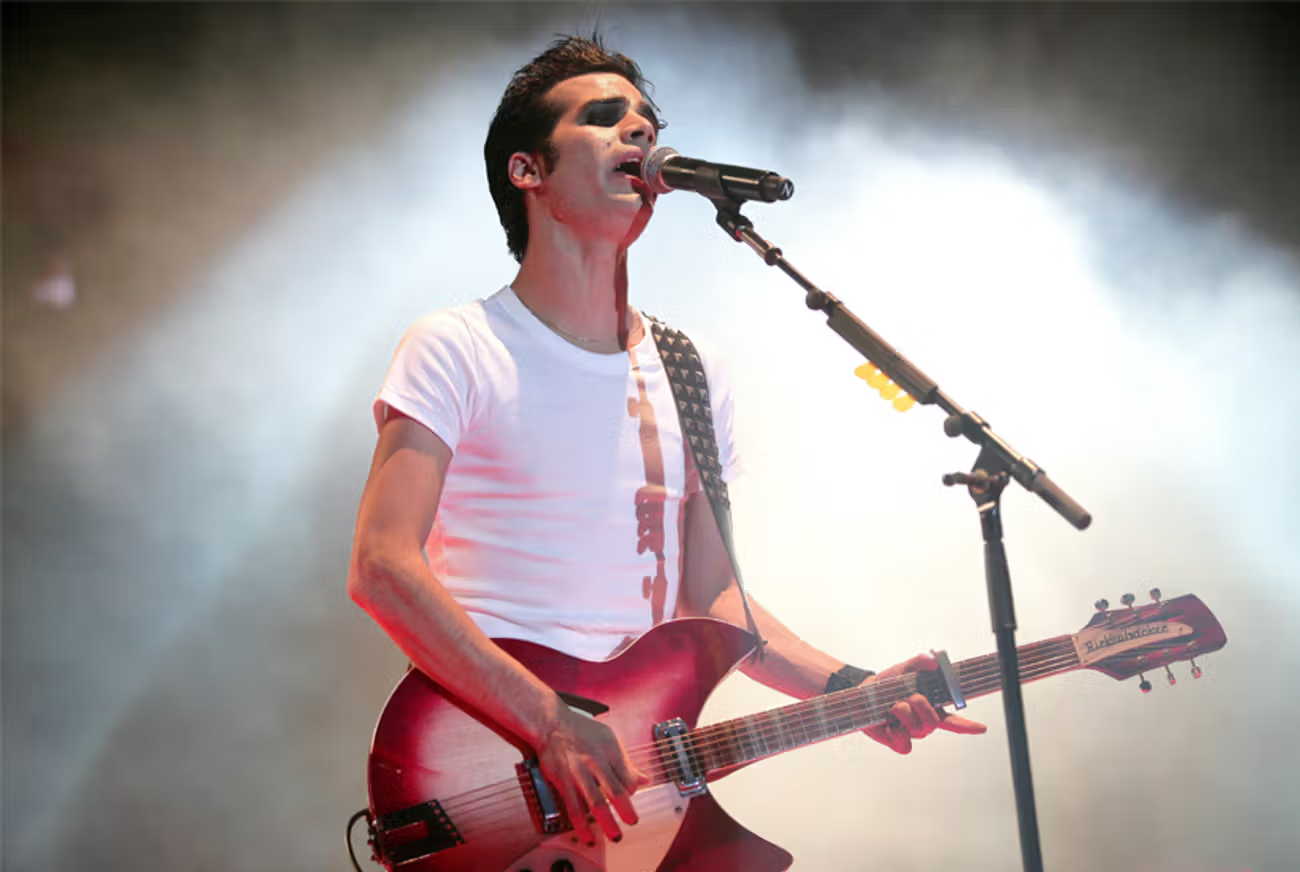

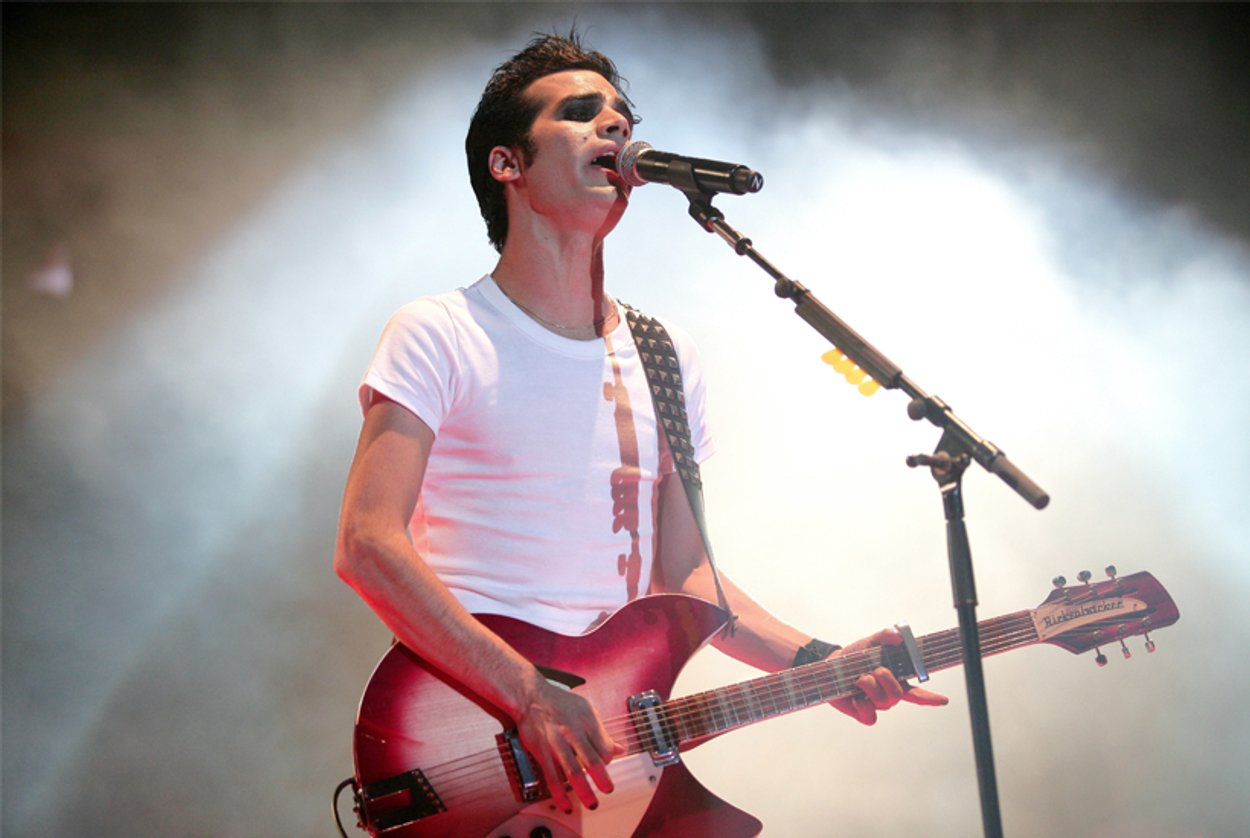

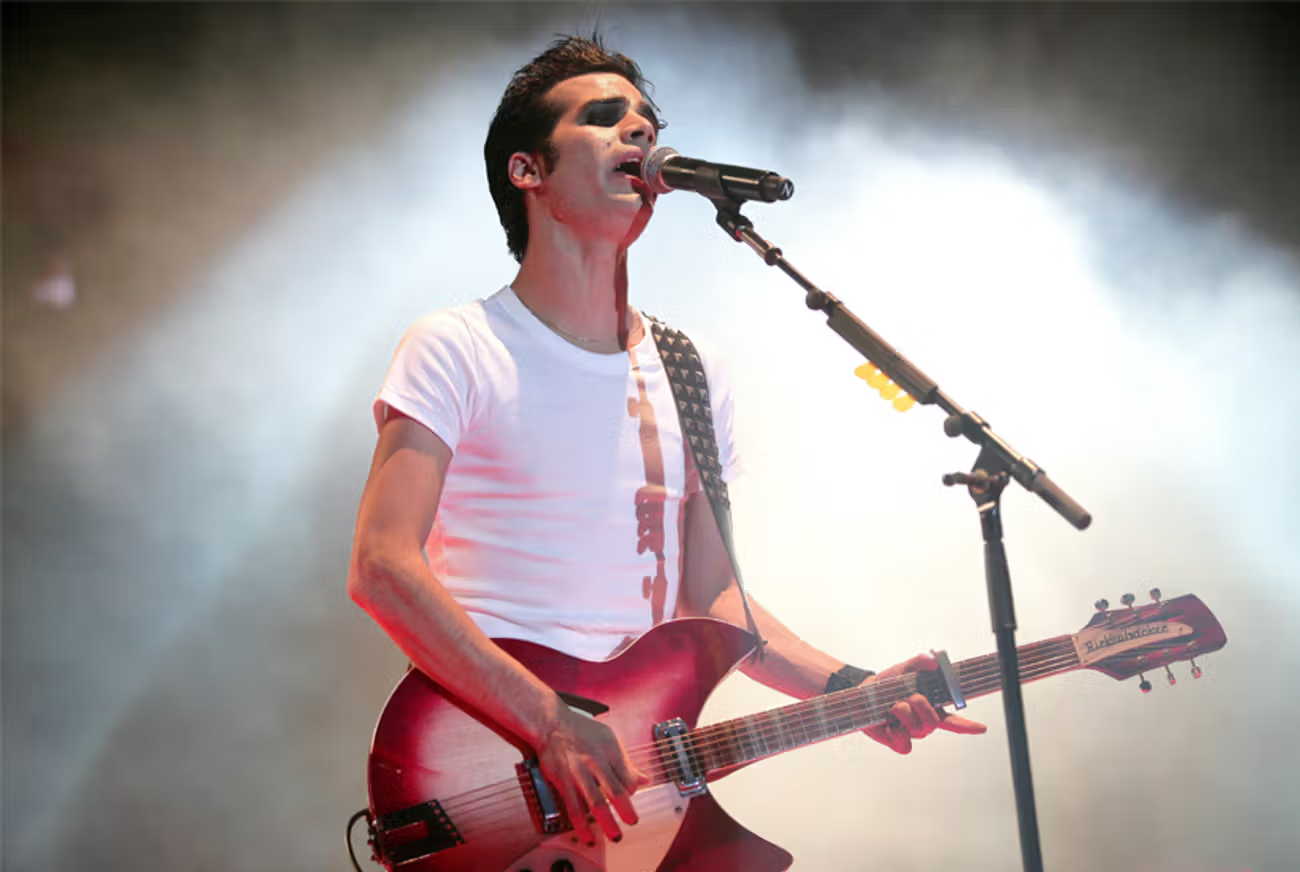

At 7.30 a.m., in the lobby of the Soho Trump Hotel, the 41-year-old singer met us to discuss in Hebrew his upcoming album. The previous evening, he performed in front of a 1,500-strong crowd at the Best Buy Theater in Times Square where, before the show was over, Geffen was topless, his pale, lanky frame betraying that neither the gym nor the beach is a favorite pastime.

But at the same time, Geffen’s name was never associated with drugs, he is happily married, for the second time, and his 7-year-old, Dylan (after Bob), traveled to New York under the watch of a self-proclaimed “obsessive father.” Look for a vice, and you have him lighting cigarette with cigarette, which probably now indicates uncoolness. His digs at society, too, seem calibrated to inflict just the right measure of pain to cause his audience to flinch, but not to trigger an expulsion from stardom.

***

In New York, Geffen learned that his cousin Assi Dayan, Moshe’s son, had died at 68 in Tel Aviv. Assi Dayan was a prominent Israeli filmmaker, screenwriter, and actor. No cause of death was given, but for several years Dayan’s health and finances were reportedly unstable. Though it seemed an easy comparison to make, Geffen dismissed relating the Dayan family to the Kennedys. “We have the alcohol and cocaine but not the Kennedys’ money. The notion of Israeli aristocracy is bullshit,” he said.

On stage Geffen dedicated the song “DNA” to Assi. In the interview, he framed Dayan’s death as yet another instance of the “suicidal tendency” of the Dayan tribe. “My grandmother committed suicide, and so did my aunt,” he said. Dayan’s death, too, was “a suicide committed in the course of several years.” He went on: “He was very talented but he dated young women and sniffed Ritalin. To live alone at his age is very difficult. He always craved attention. He committed himself to Abarbanel”—a psychiatric hospital—“but the moment he was out he rushed to publish his personal experience there. He took advantage of the media, and the media took advantage of him, and he loved it.” In Geffen’s rendering, the father figure looms large: He accounts for Dayan’s creative thrust as an attempt to prove Moshe, the harsh father, wrong.

What is clear is that in the Dayan family, love has a bitter aftertaste. “Lior [Assi’s son] told me his father had my picture over his bed. Assi loved me, but we had a love-hate relationship. My most vivid memory of him is when I was 12. He came in the evening, probably after he had snorted cocaine all day long, and said, ‘By tomorrow morning you’ll have a present from Uncle Assi, a synthesizer.’ The next day I woke up early full of anticipation. I’m still waiting for the present.”

For all Geffen’s personal focus, he’s never been away from the public eye. In the massive 1995 peace rally in Tel Aviv, he stood alongside Yitzhak Rabin and performed “To Cry for You” which he wrote about a childhood friend who died in a car accident. The prime minister’s assassination as he was stepping down from the platform made the song the nation’s mourning tune. The highly personal was accorded national significance.

In New York, to an audience unfamiliar with his hits in Hebrew, Geffen can’t build on his stardom at home. Israeli popular music is still very much a local business, unlike other Israeli cultural exports—think of television formats such as Homeland and In Treatment, which have been successfully reproduced in foreign markets. Outside Israel, Geffen performs mainly as part of Blackfield, a collaboration with the British rocker Steven Wilson that started in 2000, when Geffen, a longtime fan of Wilson’s band Porcupine Tree, arranged for Wilson to perform in Israel. Blackfield released four albums and toured the United States and Europe. The New York concert was Wilson’s last. He told the audience that “Geffen is a genius in creating three-minute pop songs, but I have a hard time creating tracks shorter than 20 minutes. Blackfield is not my forte.” So, it is now up to Geffen to decide where Blackfield is heading.

“It’s a miracle, one brought about by hard work,” he said of the band. One reason Israeli pop music has had limited international outreach, Geffen held, is that “the Israeli accent is a big obstacle. It’s heavy on the ear, even in the era post Bjork and Sigur Rós,” successful artists from Iceland. “People despise the Israeli accent.”

Another reason that there hasn’t yet been an Israeli ABBA, he continued, is the work ethic of Israeli musicians. “The Israeli music industry is quite lazy,” he said, citing the example of Ninet Tayeb, a 30-year-old Israeli singer whose career rocketed after she won in 2003 Kochav Nolad, the Israeli version of American Idol. Geffen produced Tayeb’s first album in 2006 and is critical of his protégé’s impatience. To break into international territory she enlisted in 2011 the help of Mike Crossey, a British producer. Here’s the rub: “On the day she arrived in Liverpool she posted to Instagram her selfie having a beer. It’s lots of show-off. It’s common for Israeli musicians to desire success without putting in the work. The order should have been work first, Instagram later.”

Geffen’s latest gig is serving as judge, one of four, on The Voice, the Israeli edition of the primetime singing competition. “I was not corrupted,” he said about his role in the reality show. “I haven’t changed; it’s the mainstream that has changed. Being true to myself has been my best policy. I don’t feel there’s anything dishonest here. I advocate for secular values in the show. Moreover, each minute I’m on the screen serves young musicians well. I inspire them to strive for success despite all the difficulties in Israel.”

Yet in today’s music industry, whose tone is set by the loosely defined Mizrahi music, Geffen is less commanding, and the increased competition is reflected on the show. In what seems an orchestrated internecine culture, Geffen exchanges snide remarks with Sarit Hadad and Shlomi Shabbat, the prominent players on the Mizrahi music scene. In Geffen’s reckoning, “We lost to Mizrahi music, but Mizrahi music lost as well.” The lose-lose alludes to the scandals that have embroiled Eyal Golan and Margalit Tzan’ani, top singers in the genre. Geffen said, “The Mizrahi stars received a fancy car, which they returned with the upholstery torn, alcohol spilt, and dollar bills scattered, and hookers in the front seat.”

On stage in New York, however, the only explicit reference to Geffen’s Israeli identity was the song “Go To Hell,” which he dedicated to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Geffen spells out the decision: “Bibi is detrimental to Israel. I’ve just been to Germany where senior officials explained to me the extent to which he’s unloved outside Israel. He’s not a courageous man. If he only wanted to, the peace process could have taken a leap forward. His strategy is fear, for instance, concerning the Iranian threat. His policy is that fear among the people breeds silence. That’s a primitive method.”

Given his interest in politics, and family background, it makes sense to hear Geffen muse about a position in government. “I could certainly do a better job than Piron”—Shai Piron, he means, the education minister. His model is Yair Lapid, the TV anchor and Yedioth Ahronoth columnist who, having led his Yesh Atid Party to the second-biggest gain in the 2013 Knesset election, is now finance minister. “I wouldn’t have it as easy as Yair because his past portfolio hadn’t included rock ’n’ roll, makeup, and dressing up in women’s clothes. His transition [to government] was fairly easy. But such obstacles wouldn’t hinder me,” Geffen suggested. “It’s the shelving of my music that’s a concession I’m not yet willing to make.”

Yet in five to 10 years, Geffen said he can imagine himself in national politics. “There’s a generation that grew up on the agenda I led. The problem in Israel is that the outcry during the Tents Protests”—the so-called J14 protests of the summer of 2011—“didn’t materialize. I recall a concert of Eyal Golan in the most prestigious square in Tel Aviv, amid Dolce & Gabbana and Bank Hapoalim, and no glass was shattered. That Dolce & Gabbana survived the event unscathed says it all.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adi Gold is the New York bureau chief at Yedioth Ahronoth. Yoav Sivan is a New York-based journalist.

Adi Gold is the New York bureau chief at Yedioth Ahronoth. Yoav Sivan is a New York-based journalist.