The Twin

A newly translated tale of defiance in the death camps, from the Yiddish master

This happened in the Aladdin Cafeteria on the steep hills of the Old Jaffa seashore. This cafeteria with the intense blue dome, blue like laundry bluing, old-fashioned glass windows set in narrow frames, steps made of marble excavated out of the very earth, which belonged to another time and another building, descending now a couple of stories into the depths of the mountain to a glassed-in terrace cut into its curved face.

I allow myself betimes to disappear down there away from my table, from my work, from ghosts and people, particularly during the day, when the cafeteria is nearly empty and no one keeps me from weaving the sea’s weeping into my silence.

From here, the sea’s edge, the prophet Jonah fled to Tarshish ...

I’m in the Aladdin again today. It’s a spitefully humid day. The sea air is limp. It floats face up on the small, shattered waves, and the gap in the air over the sea is the color of the inside of a mother-of-pearl shell.

A locust hatches in weather like this.

I have an idea, which progresses to a vision: The waves opposite me are not waves but the grandchildren of the whale that swallowed Jonah.

And as I chat with those darling grandchildren, the terrace suddenly turns into a glass whale. An evil darkness descends over the sea, slashing it to pieces with a glowing diamond. Galloping rain over the waves’ battlefield. Extinguished, the light of midday with its candelabrum of matte milk overhead and its candelabrum below.

This all happens so hastily that the white waterbirds can’t finish composing their letters, and they too are trapped among the slats of rain.

However, according to the clock it’s now noon, and in the glass belly of the whale there are only a few guests: a drowsing old man with a newspaper in his drowsy hands; a snuggling couple like two thick branches of one, let’s say, tree of love; a woman with a black veil over her face; and me, the witness to all this. Nevertheless, the cafeteria manager takes such pity that he orders the lights turned on. The bulbs manage but a blink and like freshly decapitated snake heads go out with a hissing of tongues.

On the outside of the windowpanes, which chatter like teeth, a cloud floats by, earth that has made its way up into heaven, a fiery plow in its breast. I see its reflection: The woman with the black veil is sitting at my table right now. The storm slapped the glass whale and slid the woman over to me, together with the chair.

Six digits carved into her left arm, ending with a one and a three.

Thirteen. The number is relevant to me. My birthdate ends in a one and a three. The house where I was born was also stamped with a 13. Later, that same number found its way to all my abodes, inns, and hotels, and it snuck, masked, into all sorts of figures and numbers that bear some relation to my wanderings over the earth. Occasionally it divided like an amoeba and doubled. Here it supposedly disappeared—say Kaddish for it—and there a new transformation. And always just at the right time. It would be easier to rid myself of my own shadow than to separate from this enchanted partner. On the other hand, why should I try freeing myself? It wouldn’t be any better ...

“No, it wouldn’t be any better,” the woman barges into my thoughts, the black veil on her face: one cloud on top of the other, glowing tiger spots along the edges. “It won’t be any better and it won’t be any worse, it’s just exactly as you wrote:

“ ‘I have tasted no other life

And don’t know if terror is more delectable—’ ”

“Who are you?” I grab her wrist where the six digits are carved in with the one and the three at the end, and both palms wrestle, each trying to bend back the other. Our breaths struggle as our hands wrestle. The woman’s breath is accompanied by a warm tongue, salty and sweet together. The dazzle of a shattered mirror infiltrates.

“Who am I?” Her face furrows behind the veil. “A good question. I’ve asked that of the One and Only for years, and may he forgive me, but it’s like I’m talking to a wall. Possibly there’s an answer on the other side of the wall, but my head and heart are already burdened from sitting. And you, so impatient, want to know who I am.” And suddenly the veiled woman bursts out laughing, the firestones of her laughter rolling down into my throat. “In any case I will tell you who I am. The One and Only has already forgotten who I am, but for me, his creation, the memory still flickers. Thus mark my words: I sought you out, and found this cafeteria by the sea, just to tell you who I am.”

I can still feel her vanished laughter rolling in my throat. But now the laughter is mixed with the crying of the sea and the rain. “Do you remember the name Myron Marcuse? You must remember, because Myron Marcuse was your neighbor. You lived at 13 Vilkomir, and him—across the street. If not him, you should remember his daughters, who the street called The Little Twins, though each one of them was anointed with a different name and a different soul. The younger one was named Hodesl and the older one, born all of 13 minutes earlier, Grunye. And that, then, is me—Grunye, the older sister.

“I am Grunye, but I’m not sure. Until our premature adolescence we were as alike as two tears from the same eye. Ribbons were braided into our hair, Hodes a blue one and me a red one, so that people wouldn’t mix us up. In high school we used to prank the boys—when Hodes had a rendezvous on a moonlit night, it was me, Grunye, who came, and vice versa. Only rarely did a suitor figure out that he was courting the other one. Most times we both ruined the game. Outsmarting or fooling the boys got to be a habit for us, second nature. But when the game got too serious, we stopped the acting—it could even go so far that someone in love with Hodes might want to commit suicide because of her sister.

“On the other hand, our souls were different, so no one had to braid any ribbons into them. Hodes was a born violinist. At 6, like Mozart, she gave a concert with the city philharmonic orchestra. Someone said then that Hodes had put a white handkerchief on her shoulder because her violin was crying. Her music teacher quipped that instead of red blood cells, red violins coursed in her arteries. In my blood—the music of revolution. I would have stabbed out my own eyes if it would have made things brighter for my neighbors. What good is abstract brightness when you’re blind yourself? I wasn’t grown up enough for such an elementary idea. While I was handing in the last exam on graduating the Realgymnasium, I was caught in an iron net. I was accused of doing away with a provocateur on Belmont, that fir-covered mountain that Napoleon named, and where we teenagers carried on love affairs.

“Myron Marcuse was our stepfather. After the tragedy with our father—he was cut to pieces under a train—he married our mother more for our sake than for his own. During the day, Myron Marcuse was a goldsmith, and at night a thinker, a philosopher. He carried around a theory that the reason for all tragedies, individual and societal, is jealousy, and when you’re jealous you’re capable of anything. If Homo sapiens were cured of the disease called jealousy, they would turn into angels on the Earth. For years he performed psychophysical experiments on goats, dogs, snakes, wrens, and two baby monkeys, which he had bought off a Roma. Our courtyard looked like a zoo. Finally he extracted a kind of serum, which he called antijelin, which was also the name of the brochure about his theory that he published in three languages: Yiddish, Hebrew, and Polish.

“When Chaim Nachman Bialik visited our city, Myron Marcuse sent his brochure in to him and requested an audience. The poet received him in the Palace Hotel, where he was staying, and chatted with him for a few hours. Myron Marcuse later related that Bialik was impressed by his theory. He expected that when Bialik returned home to the Land of Israel he would be the messenger for Marcuse’s teaching. He’d give speeches to make people inject antijelin into Jews and Arabs alike, creating peace between them. First though, he’d inject himself with antijelin so he wouldn’t be jealous of the young hotshot poets.”

In the glass whale, the runaway clouds turn paler. A buzzing meteor—a flea. The channel of the sea floor, like an inside-out sleeve, is turned right-side out again. Grunye pauses in front of the rain. If it cried it out, the rain would feel better. As she puts a cigarette into her mouth, a bolt of lightning comes along and does her the favor of giving her a light.

Dull, sulfurous circles—wedding rings for dead brides—approach and are left hanging on my eyelids. The odor and taste of home-brewed Passover mead sticks to my palate.

The black veil disappears, and a veil of drunken smoke weaves itself over Grunye’s face. The spun material gets thinner and thinner, turning into wrinkles. She is silent. But now the cigarette is about to wink out into nothing and, sated with its ash, she continues: “His antijelin didn’t manage to redeem humanity, but it did redeem him. While flogging the Jews into the ghetto with his whip, Myron Marcuse injected himself with a considerable dose of the godly serum and was redeemed from jealousy for eternity. Our mother needed no antijelin. She was jealous of no one but the dead. The Almighty had let her into their kingdom.

“Hodesl was a famous violin player. My sister played on the strings and me on the chains. In the death camp the strings became chains as well. Here we became alike again, Hodesl like me and me like Hodesl, like two tears from the same eye. The few who remembered us in the camp from our childhood and youth crowned us with the title The Little Twins, as a sign that the world is still the world and what it used to be.

“Everyone in the camp was little twins. The crematoria turned us not just into little twins but into hundreduplets and thousanduplets; one could not distinguish between a man and a woman, a child and an old man; everybody wore the same clothing and everyone’s head was shaved, and every skeleton, as you know, has the same smile—but even so only Hodesl and I were called the twins.

“Not just our faces or bodies but our souls too, Hodesl’s and mine, were twinned in the camp, if not like twin tears then like twin sparks from the crematorium. If we had girl secrets, ambition secrets, love secrets, we shared them like we shared crumbs of bread and shards of bone. Subconsciously we probably wanted to hide our secrets with each other. Secrets want to survive too, they want to live long enough to be revealed. When one of us is saved, the other’s secrets should be saved too.

“Now I am coming to the most important part of my story, the reason I sought you out and found you and the reason why you are, if not a whole, then at least a half twin.

“We were really close neighbors. We grew up on the same street, and the same sleet bathed our hair. The same swallow skipped and sang from my roof to yours. You used to come over to our house, giving me your improper looks. I didn’t get anywhere by flirting with you. I was too earthbound. It happened that you came into the workshop to listen to Myron Marcuse bang his hammer or to chat with him about his antijelin. I didn’t have the guts to barge in. But a hammer banged away in you, and its echo resounded with the hammer that beat in my sister. No, you never mixed up the two of us.

“Among the secrets that Hodesl hid within me was the secret of the two hammers.

“You still don’t understand why I looked for and found you? I was left with one passion: to wander across the world and kiss her memorial clouds. Maybe her image was preserved somewhere? Maybe there’s someone alive who heard her play? Maybe a heart that trembled with hers still trembles? I didn’t go to Paris because of the Louvre; I carry a Louvre in myself where an insane God hung his paintings. I flew to Paris to lay a bouquet of roses on the grave of a music teacher of Hodesl’s.”

“Music. I have no other name for it. Human is also a name for all humans. Just like Albert Einstein was born, Siegfried Hoch was too. Siegfried Hoch, commandant of the camp, had already tasted all human and animal pleasures, like the chef-de-cuisine in a hotel tastes every guest’s prepared dishes. Only an orchestra was missing for his New Year’s. So he gave a speech to the numbered skeletons: If there were any musicians in his kingdom, he would hire them for at least a year.

“Musicians appeared quickly. Famous musicians from Poland, Hungary, Austria, Holland. For them, Siegfried Hoch broke open the storehouses of plunder, and under fingers thin as strings and pale chewed lips, he saw cellos, violins, clarinets, and flutes come to life.

“Hodesl didn’t want to reveal her artistic profession because she didn’t want to be separated from me and had no wish to become only a half twin, and also because she didn’t want to play for the Angel of Death. Like a mother, I insisted she join the orchestra. Maybe Hodesl could save herself this way.

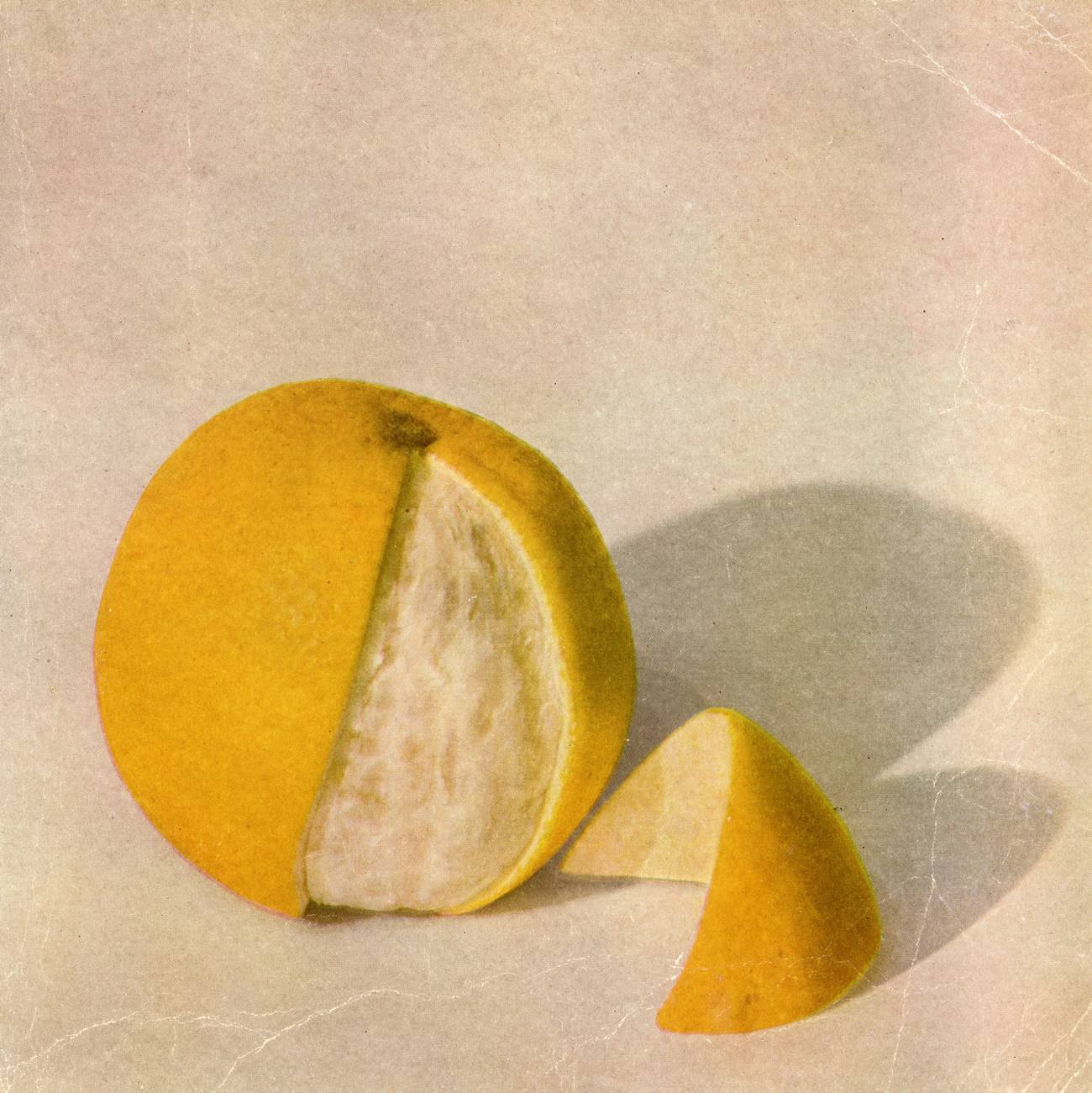

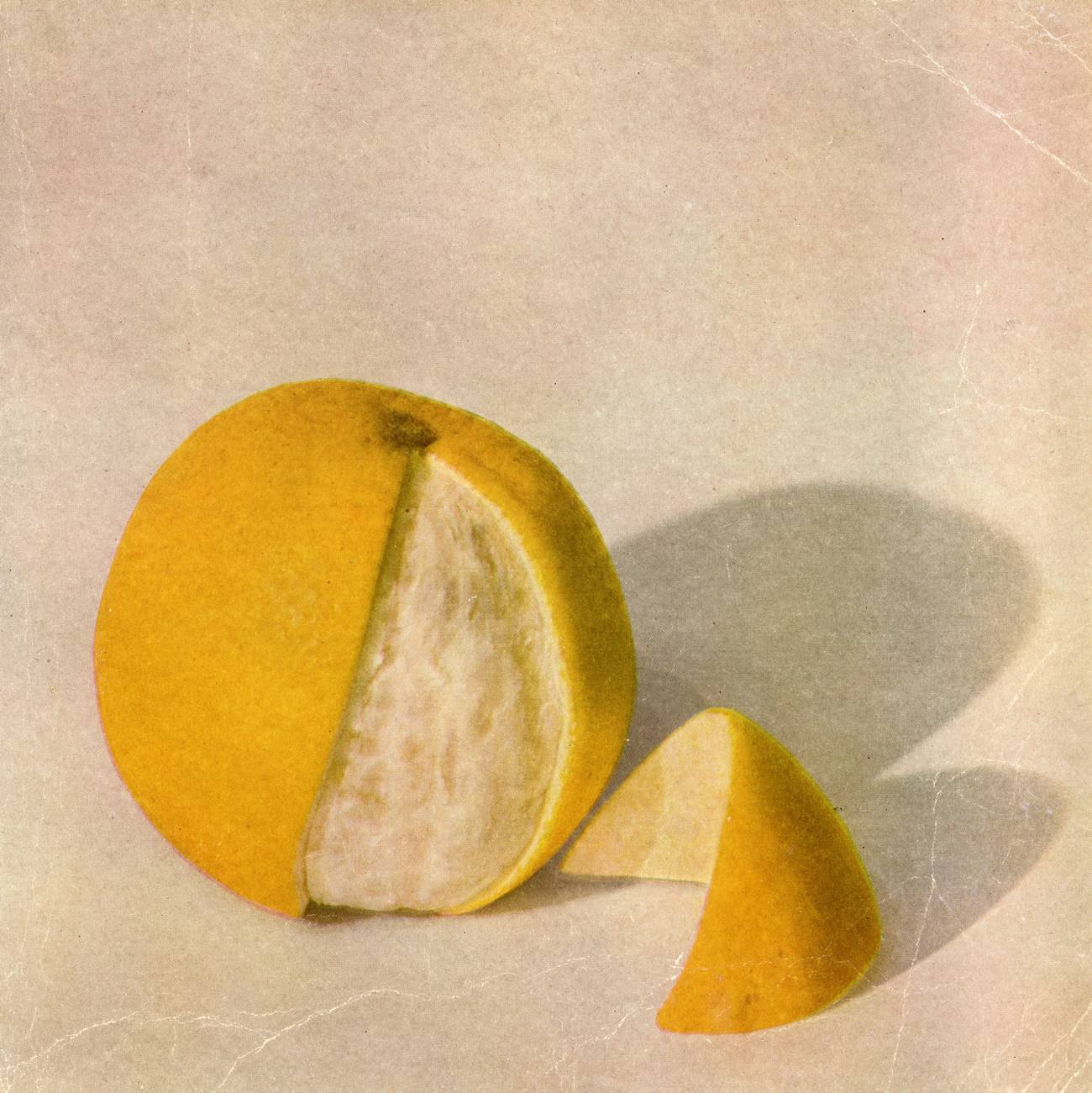

“It was New Year’s Eve, 1944. Siegfried Hoch sat on a podium, bundled up in a puffy white fur coat and a fur hat pulled over his bitten-off left ear (done by a Warsaw girl whom he drove into the gas chambers), peeling oranges and stuffing his mouth with them, tossing the peels into a basket.

“In front of him was the gymnastics court, and in the middle of it was a gallows from which the air hung in a noose, with its blue tongue sticking out. With the gallows and black, twinkling snow in the background, like blackbirds between earth and heaven, the musicians, barefoot and winnowed by biting frost, played Beethoven’s ‘Eroica.’ The conductor, a maestro from the Vienna Philharmonic, tossed his long, flowing sleeves and tried to grab the baton like a drowning man grabs at a straw.

“The ensemble, with Hodesl playing first violin, tore open the purple heavens. The audience curled out of the smokestack with ashen faces. When the maestro bowed, moans of applause were heard. The commandant was also clearly moved. He piled up a big stack of orange peels and tossed it at the musicians.

“Even before the orange peels managed to glimmer into the snow, the musicians—like eagles with broken wings—swooped down to snap up the gift. The conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic, the baton between his frozen fingers, displayed a virtuosic nimbleness in hurling himself at the delicacy.

“And Hodesl? She alone stayed frozen on the gymnastics court with her violin clutched to her heart. She was too embarrassed by the ashen faces, the violin, and the ‘Eroica’ to kneel before the white fur coat and its orange peels.

“At the moment that separated those two non-Jewish years, the old and the new, the commandant wobbled into our block and called out Hodesl’s number. I was the first to jump up from the wooden bed and stand at attention. Both of us then, Hodesl and I, were twins in the camp. I prayed that my sister with perfect hearing would go deaf, become deafened by a dream. The commandant had already led me out of the block and to the gymnastics court, where the gallows looked like its own shadow either falling forward or standing still. My breath melted the ice air, and setting a pace in that direction was easier.

“My prayer was not heard. The other half twin raced after the first—Hodesl showed the commandant her bare arm and the true, carved numbers. They shone like stars.

“The stars still shine in them. The numbers of my Hodesl were extinguished forever.”

Grunye lights a fresh cigarette from the last spark of the previous one. This time, it seems, with a specific intention: to weave a curtain of smoke between us.

Why doesn’t she want the sea to foam in its darkness? Why is she scared of a splinter of sun?

I want to ask her this. I have a lot of other questions. But my words go out like so many stars embedded in Hodesl’s arm. Once again the taste and scent of old-time, homey Passover mead sticks to my palate: “I told you one passion remained for me, wandering around the world and kissing the little clouds of Hodesl’s memory. Cuddling up to those who loved my sister. Truth be told this is my second and probably last passion. After the so-called liberation, I had no other desire than to follow the traces of Siegfried Hoch. There is no corner of the earth where I didn’t lay my traps for him.

“When the commandant disappeared in his puffy white fur coat, the camp inmates looked like gasping fish on the bottom of a pond where the water had run out of the sluices. Taking in the fresh air was not enough to live, to feel one’s own wounds and enjoy their harm. To live one had to breathe death. A magnetic needle showed me where I should travel. The first station the magnetic needle showed me as my destination was our hometown. I found the gold that Myron Marcuse had buried under the cherry tree in our garden. It was in a box of gopherwood, together with several ampules of antijelin and his brochure with the same name. The roots of the cherry tree held out the box with their cut-up fingers, as if they had sucked the color and the energy of the cherries from the buried gold.

“Do you remember the name Zvulik Podval? His father was Tzole the chimney sweep. They lived near the pump next to the first brick factory. When I was in jail due to the business with the provocateur, Zvulik was my partner and my neighbor. The same Zvulik tracked down the commandant’s wife in Linz, became her so-called lover, and sent me copies of her husband’s letters and their addresses. “It’s a big world, but America is bigger—that’s the naive saying of my grandmother’s that stuck in my memory. So I’ve searched through the world and America both; I’ve learned Burmese and looked for the commandant in a Buddhist temple in Burma; I looked for him in Mozambique among the ivory sellers; I learned how to play the part of a belly dancer, wanting to dazzle him in a Baghdad cabaret. I can speak Arabic, Turkish, Portuguese, and Spanish. I understand the languages of the indigenous inhabitants of the Americas.

“We have both changed our faces many times. Our shapes. He disguised himself as a Don Ricardo Alvarez, and me as a Doña Teresa. I lay in wait for him in the jungles along the Amazon and in the Galapagos Islands in the quiet ocean; I looked for him in the Ecuador capital, Quito, and in the Andes and at the Cayambe and Chimborazo volcanoes, where an eagle can lift a young cow in its talons.

“For how many years do you think our worldwide game of cat and mouse went on? Thirteen? But all 13 years I was the cat and he was the mouse. I made a fatal error, relying on his bitten off left ear as a distinguishing mark. But not every Cain is fated to brag about his mark. If someone can be fitted with a fake soul, why can’t someone fit themselves with a fake ear?

“Now you can hear how the international game of cat and mouse reached its finale. I was wandering in Quito at that time. A couple of months ago my mouse had become a bat. Zvulik Podval let me know from Linz that Madam Hoch was moving to Peru.

“When switching countries, and most of the time when moving cities, I always used to take a plane. It’s cleaner in the air than on the ground. Now taking a train appealed to me. I needed to meet someone. In the middle of the night the train stopped at a small station. When I got off and went into the terminal to get something to drink, a barefoot Indian took a statuette out of his chest pocket and offered it to me for sale.

“I recognized it immediately. Its eyes, like blue drops of venom on needle tips, were not at all altered. His left ear was bitten off, and the stitches that held his artificial ear together were obvious. He only lacked the white puffy fur coat and the fur hat to become the camp commandant once more. I realized right away: Siegfried Hoch had been turned into a tsantsa.

“Do you know what a tsantsa is? In the jungles at the foot of the Andes Mountains there lives an Indian tribe called the Jivaro. The Jivaro are men of war and men of revenge. When they capture their enemies, mere suspects who hide in the jungles, or policemen, they cut off their heads, drop them into kettles full of secret juices, herbs, and rocks, and boil them until the heads are shrunken to the size of a fist. The hair, wrinkles, freckles, and moustaches are still there. That kind of head is called a tsantsa. The trade in tsantsas is definitely forbidden—yet the opium trade is forbidden too! Modern man likes the unusual, the forbidden, and tourists pay high prices for such shrunken heads. A tsantsa without a pedigree is cheaper. A tsantsa from a hangman is much more expensive. I was told that family members paid $10,000 for the tsantsa of a minister.”

The whale with a rainbow tail swims into Old Jaffa. The sea tried without success to break the chains and escape from shore. It surrendered to a cosmic field marshal. The storm flees too on its violin-string legs.

Here is the old man. The newspaper is still stuck to his glasses. He read it before in his dream, and now, on waking, the news is—old.

The branched-together couple splits sweetly apart, but the unseen roots are attracted to the same well.

And Grunye? Still veiled, only the 13 on her bare arm is illuminated by a pink ray of sunlight.

Fiery clouds reveal themselves on the horizon, and behind them a round, small sun swings over the water.

Suddenly, Grunye gets up from the table, and the black veil is ripped asunder by a mourner’s tear.

“He’s peeling oranges again, the merciful one, and he’s throwing the peels into the snow, at the musicians. Hodesl will not bow, Hodesl will not bow!”

Excerpted from Sutzkever Essential Prose, translated by Zackary Sholem Berger, with permission from White Goat Press 2020.

Avrom Sutzkever (1913-2010) was a Yiddish-language poet.