Balkan Mystery

In Leeches, a novel by the Serbian Jewish writer David Albahari, Belgrade plays home to nationalists, anti-Semites, and kabbalistic puzzles

The fad for novels about golems and gematria and other Jewish mystical oddities seemed to have run its course a few years ago. There was always something a little suspicious about the eagerness of writers to seize on these Hollywoodish elements of Jewish lore. Rather than engage the genuine foreignness of kabbalism and Jewish mysticism, writers from Harry Mulisch to Michael Chabon (and the film director Darren Aronofsky) tended to use them as metaphors for very contemporary concerns. Thus the golem became a superhero for persecuted Jews or a prototype of genetic engineering; the number-games of gematria were treated as forerunners of today’s computer programs or DNA base-pairs. In recent years, however, the appetite for religious sci-fi has been catered to by writers like Dan Brown, who prefers the Vatican and the Knights Templar to Rabbi Judah Loew and the Sefer Yetsirah.

That’s why Leeches, the newly translated novel by David Albahari (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $24), reads at first like a kind of throwback. First published in Serbia in 2006, the book is fully stocked with Jewish mystical props: not just the golem and the 10 Sefirot, but portals into higher dimensions, ancient manuscripts that rewrite themselves, cosmic sexual rites, souls that are reincarnated in every generation, and so on. Yet at the same time, Albahari—a Serbian Jewish writer who now lives in Belgrade, and the author of the acclaimed Holocaust novel Götz and Meyer—allows his text to be haunted by more interesting and unusual ghosts.

Most obviously, Leeches is dominated by the specters of the Holocaust and of resurgent anti-Semitism. The novel’s narrator—we never learn his name—is a columnist for a Belgrade newspaper, Minut, and as he befriends a few members of the city’s Jewish community, he becomes increasingly aware of the threat posed to Jews by Serbian nationalism. “This is one big pile of nonsense … and there is no point in paying attention to it,” he declares after reading a pamphlet about “the Aryan origins of the Serbian people and the need to preserve their racial purity.” But his Jewish acquaintances aren’t so sure: “We paid no attention to another pile of nonsense, said Jakov Svarc, and look where it got us.”

As another Jewish character points out, however, “The same thing would have happened … even if we had paid all the attention in the world”; and the more the narrator denounces anti-Semitism in his newspaper column, the more vicious and violent the response becomes. A Jewish cemetery is defaced, an art exhibition vandalized; graffiti is scrawled on the narrator’s front door, feces left on his doorstep. Finally, the threats become murderous: “We will impale you, and display you on Terazije so that everyone can see how our enemies fare.”

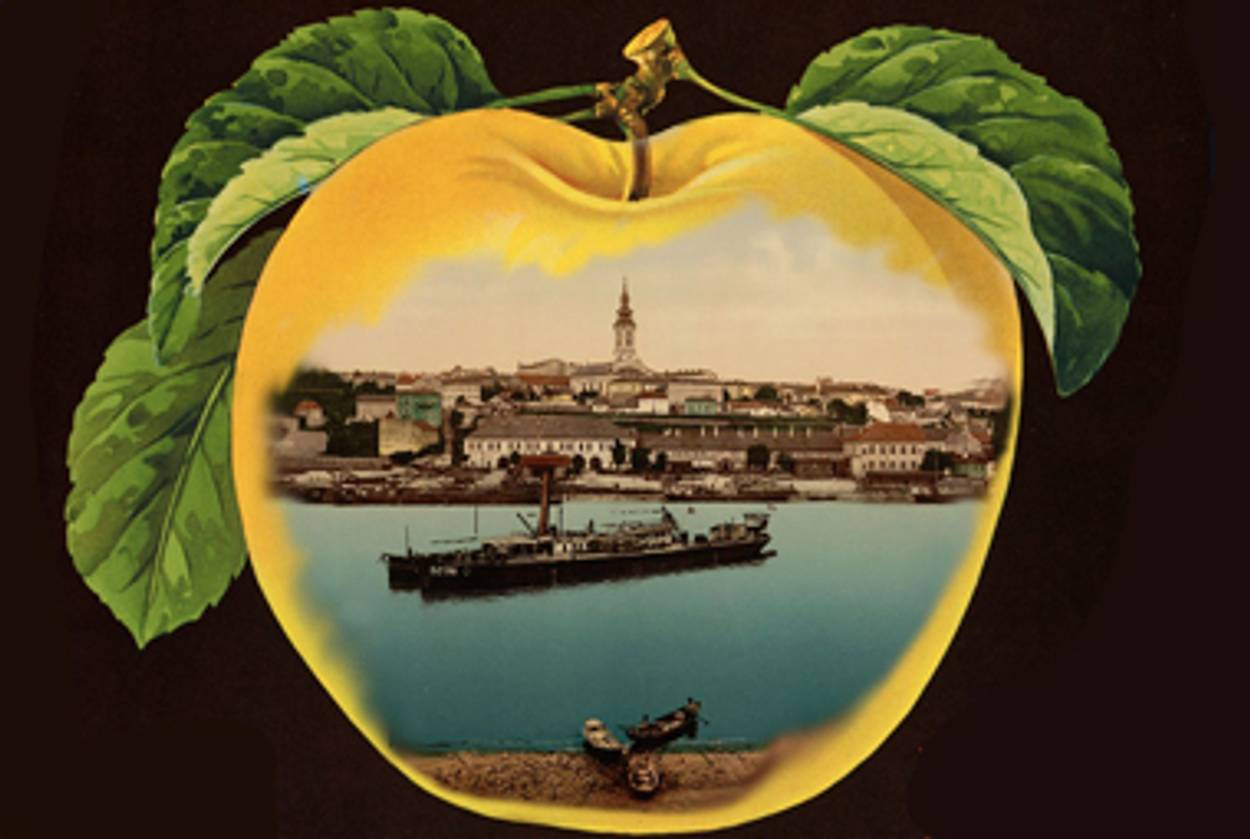

This constant drumbeat of violence is only one of the sources of the novel’s rising tension. The other, more mysterious unease comes from the narrator’s growing conviction that he has stumbled into a bizarre and intricate conspiracy. Leeches opens with a scene reminiscent of Blow-Up or The Conversation, those classic movies of voyeurism and paranoia: The narrator is walking by the banks of the Danube, eating an apple, when he notices a man and a woman having an argument. Suddenly, the man slaps the woman in the face and then turns and runs off.

The narrator, his interest drawn, finds himself following the woman through the streets: “I wasn’t thinking at all, I didn’t pause to wonder what I was up to, I didn’t say to myself that I should follow her, I simply put one foot in front of the other, and followed her.” He loses track of her in the maze of streets, but as he continues to search, something even odder happens. He picks up a button lying on the sidewalk and finds that underneath it someone has drawn a symbol, a circle containing two triangles. Nothing he has seen is inherently unusual—a fight between strangers, a bit of graffiti—yet he is convinced that there is more at work than meets the eye. “The longer I chewed on this, the more convinced I became that the explanation for the events on the quay and the woman’s disappearance lay in these mathematical relationships, and that if I were to penetrate their secret, they would lead me straight to her door.”

At first, the reader is not sure whether Albahari wants us to trust the narrator’s paranoid theories. In a nice touch, he makes clear that the narrator is a dedicated stoner—he is constantly smoking joints with his friend Marko—and marijuana is not known for promoting clear thinking. But then the narrator starts to see the mysterious symbol everywhere, and it seems there must really be a conspiracy at work in Belgrade. (Here Albahari’s allusion is to Thomas Pynchon’s Crying of Lot 49, where a certain graffiti symbol reveals the existence of the Tristero, an underground postal service.)

Albahari weaves the magic net of the conspiracy tighter and tighter. The narrator is convinced that an anonymous classified ad in the newspaper is addressed to him; when he replies to it, he is given a copy of a manuscript titled “The Well,” which seems to be a history of Belgrade’s Jewish community. But each time he opens it, the text seems different, and he keeps finding passages that describe a mystical figure named Eleazar, who seems to reappear in Belgrade throughout the centuries. The woman from the riverbank turns up again; it turns out that she is Jewish—and has a connection with the manuscript. The narrator turns to an old high-school friend, now a mathematician, for help decoding the symbol, and he too seems to be in on the plot. Even his best friend Marko starts to give him a bad feeling.

“All I want … is to understand what’s going on,” the narrator says. But it is easy to grow impatient with Leeches’ woozy, over-plotted mystery. No matter how it is eventually explained—and Albahari does explain it, sort of—it has all clearly been arranged, as in a book by Umberto Eco or Dan Brown, to give the reader a conspiratorial frisson. Juxtaposed with the real danger of anti-Semitism, the kabbalistic game seems rather indulgent.

Much more interesting are Albahari’s occasional attempts to link the Serbian predicament with the Jewish one, in provocative ways. At one point, Albahari seems to suggest that the international odium inspired by Serbia’s ethnic-cleansing campaigns in Bosnia and Kosovo led the Serbs to become a pariah people, a scapegoat, like the Jews in Christian Europe: “The horror of identity is that it can’t be sloughed off the way a snake sheds its skin, and there is no dungeon worse than an identity that one doubts or that others have proclaimed to be bad or evil. I experienced this myself many times in the years of ethnic strife, facing the prejudices about Serbian identity, and I could only assume how that must have seemed from the perspective of being Jewish or of an identity that had permanently been branded as negative.”

It’s not entirely clear how Albahari means this to be read, but it sounds like a damning statement of Serbian self-pity. If the world had a negative view of Serbia during the 1990s, it was not because of “prejudice,” but because of the Serb concentration camps that murdered thousands of people. The ambiguities in Albahari’s understanding of his Serb and Jewish identities are deeper, and more interesting, than any of the carefully contrived mysteries in Leeches.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.