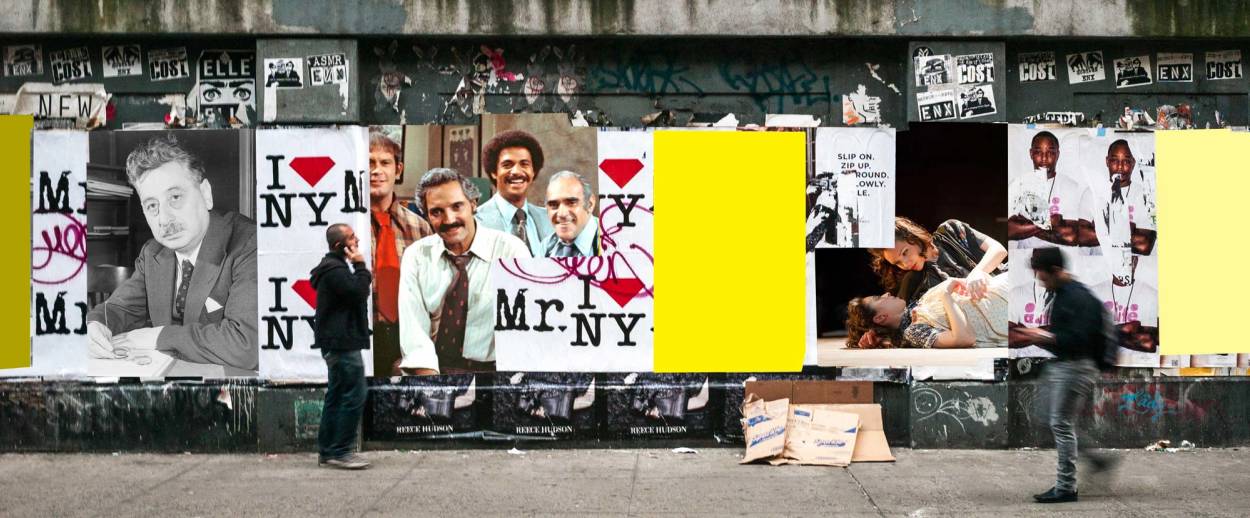

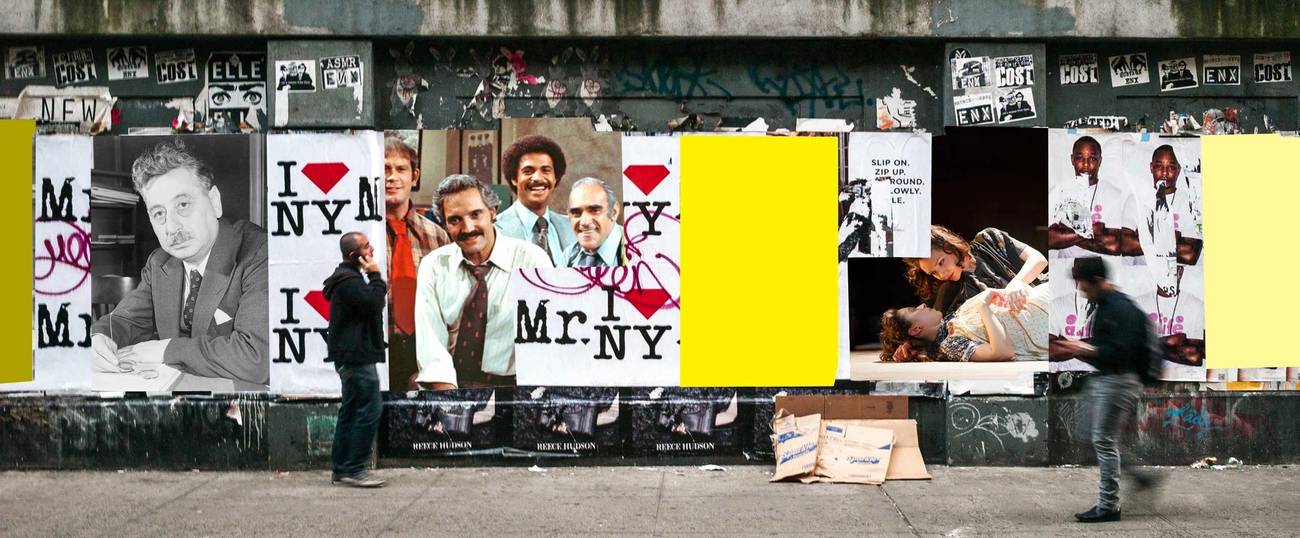

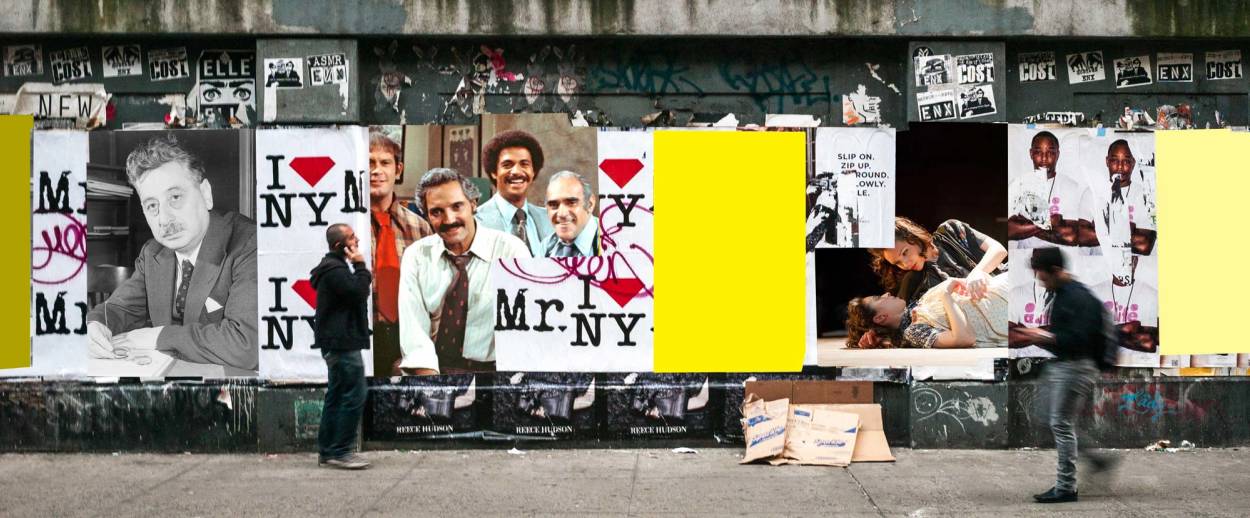

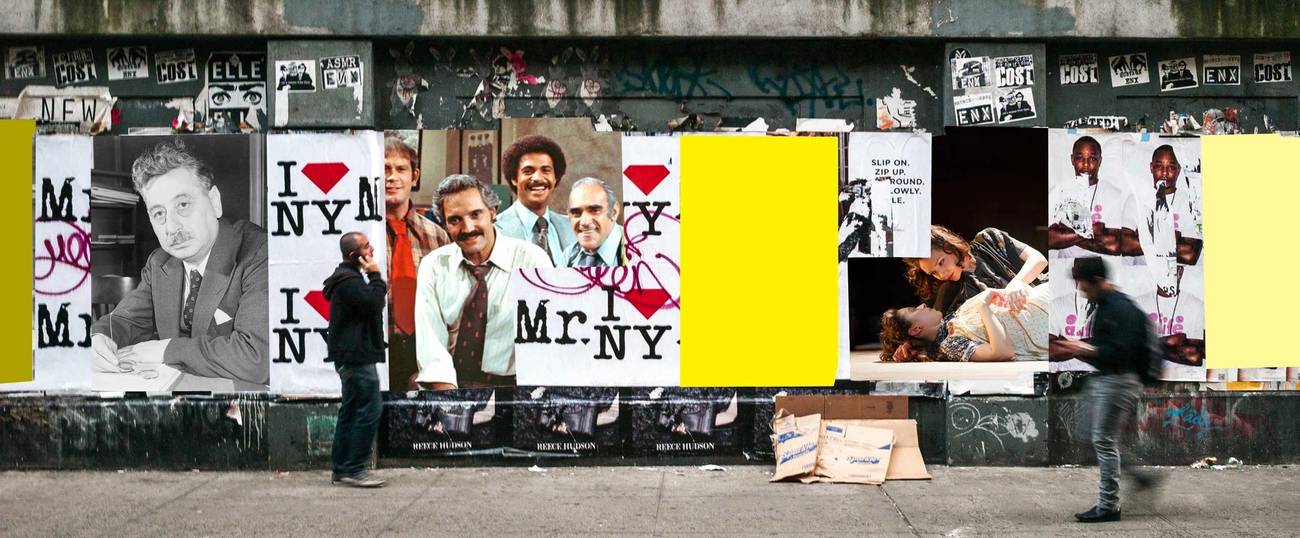

Barney Miller and ‘God of Vengeance’

Rokhl’s Golden City: What 1970s sitcom TV and 1920s Yiddish theater have in common

I recently bought the complete DVD box set of Barney Miller, never thinking that a TV sitcom set in the “Ford to City: Drop Dead” dark days of the late ’70s could actually make me nostalgic. Yet here we are. Enough said about that.

What’s pertinent here is the refreshing way Jews are depicted on the show, a workplace comedy about detectives in the West Village’s fictional 12th police precinct. You can’t help but be taken aback by the number and variety of Jews who make their way through the 1-2; and not just as victims of crimes but as criminals, too. How could I not be absolutely smitten by a 60-year-old bookie in a garish blue suit and matching fedora, alias “Nathan the Bagman”?

When the Bagman is picked up, he pleads innocent. He’s just one of dozens of Nathan Levines in the phone book, surely they’ve gotten the wrong guy, his pocket full of betting slips aside.

Rather than play Nathan the Bagman for cartoonish laughs (a Jewish criminal??), the punchline is his insistence on his deep ordinariness, he’s just one of many, a predicament I’m sure every David Cohen or Sarah Katz can relate to.

The disappearance of Nathan Levine (the one in the flashy blue suit) from American TV is felt keenly by this child of the ’80s, when so many obviously Jewish characters were either totally deracinated, cringingly Woody-esque, or for some reason, made to go disguised as Italian. Marginal Jews are just that—on the margins—and it’s all too easy to crop the family photos in a way that frames American Jews the way they’d like to see themselves rather than the way they were (or are).

Marginal, of course, is not a fixed position, and Sunday’s Tony Awards saw some beautiful bits of overdue correction. Indecent, the show about the Yiddish play God of Vengeance, won two Tonys, one for best direction by the brilliant Rebecca Taichman. Indecent is also a first for playwright Paula Vogel, a giant of the contemporary theater who already won a Pulitzer for drama almost 20 years ago but had to wait until 2017 for a Broadway production.

There’s also the matter of the play within the play. God of Vengeance is about a man, Yankel, who runs a brothel while desperately trying to keep his daughter out of the family business. And, as the publicity for Indecent has so prominently pointed out, the daughter, Rifkele, rather than be kept prisoner of Yankel’s bellicose holiness, allows herself to be seduced by one of his girls, Manke.

God of Vengeance played all over Europe between 1907 and its Broadway debut in 1923, where it opened, and then quickly shut down, followed by a trial for obscenity. Winning a Tony for Indecent is a delicious postscript on the ignominy of 1923.

Indecent has made much of the fact that God of Vengeance was the first kiss between two women on Broadway. And that’s true. But by the time God of Vengeance made its way to Broadway, audiences were hard to shock. Indeed,“[t]here were so many plays about prostitution on Broadway in the early 20th century that critics complained about the number.”

God of Vengeance probably would’ve been just another of these “brothel dramas” but for a prominent Upper East Side rabbi railing against the very indecency of such a play. He might’ve even called it a shande far di goyim (dirty laundry not to be aired in front of non-Jews) if it were permitted of high Reform rabbis to utter a Yiddish word.

The framing of God of Vengeance by Indecent raises some interesting questions. In The Wall Street Journal, critic Ed Rothstein dinged Vogel and Taichman for creating a God of Vengeance that never existed, one that is far more feminist, queer, and liberated than the play Sholem Asch actually wrote. And he has a point. Having now seen God of Vengeance in two separate Yiddish-language productions this year, I’m here with the least popular take of all: Indecent is funny, sad, deeply entertaining and original. God of Vengeance, on the other hand, is not. What’s worse, its female characters are two-dimensional, their love a mere plot point meant to bring down our tragic hero to his inevitable downfall.

Rather than seeing Vengeance as a play about two women fighting to be free, I saw it as a mystical reaction to the vulgar inevitability of modern life. Yankl Tchaptchovitch lives in an apartment over his brothel, keeping his virginal daughter caged upstairs, going so far as to install a Torah scroll near her to keep her pure. His home is a Hasidic gartel (ritual belt) writ large—a physical separation of the upper holiness and lower profane. The tragedy, of course, is that such separation is impossible in the modern world where money, not God, is at the center of Jewish life. The good thing is that tragedy, and history, are perfect materials for great art.

***

Listen: The Rialto Report is just another oral-history podcast focused on the lives of working men and women. In this case, those men and women are part of the adult-entertainment industry. Unsurprisingly, Jews have played a significant role in front of the camera and behind the scenes. Marty Hodas almost single-handedly created the peep shows of 42nd Street. (N entirely SFW.)

Research: At the New York Public Library, learn the lesser-known stories of gay and lesbian Holocaust survivors.

Experience: A new multimedia exhibition devoted to the history of the American Yiddish stage, focusing on its indelible musical legacy, from California’s Milken Archive of Jewish Music.

ALSO: Egg Rolls, Egg Creams, and Empanadas are among my favorite food groups. They also form the base of the annual cross-cultural music and food festival by the same name, Sunday, June 18, Eldridge Street, on New York City’s Lower East Side. Don’t forget the sunscreen. If you prefer indoor activities, check out this introduction to genealogical databases at the NYPL Mid-Manhattan branch, Saturday, June 17. Finally, Pete Sokolow is one of the greats of the contemporary klezmer and Jewish music scene. But to call him a “klezmer” musician is to elide his considerable reputation as a hot jazz and Dixieland pianist. Monday, June 19, the Yiddish Artists and Friends Actors Club will present a musical tribute to Pete featuring an intergenerational lineup. For tickets contact Ruth at (516) 569-1678, all seats reserved, $25.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.